Media | Articles

The 1907 Thomas Flyer circled the globe in 169 days—without roads or maps

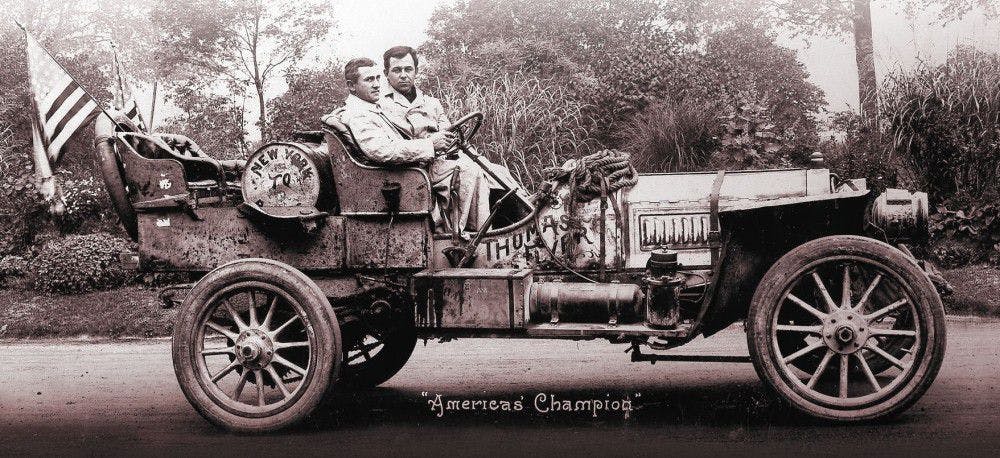

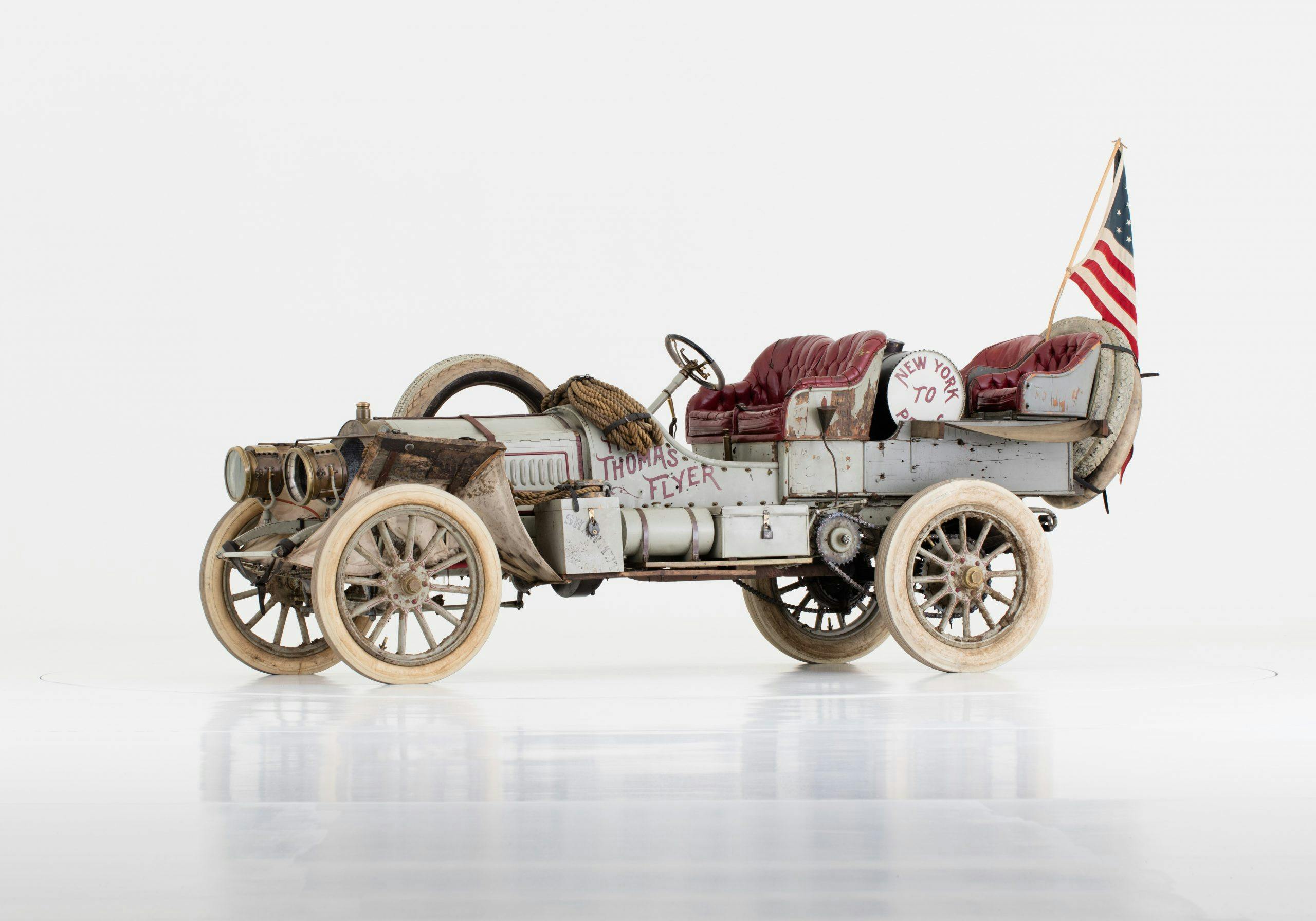

The fictional Leslie Special, driven by Tony Curtis in the 1965 comedy The Great Race, has nothing on the real thing, the 1907 Thomas Flyer. Winner of the first New York-to-Paris ’round-the-world car race in 1908, the Flyer required no movie tricks to successfully complete the historic endurance race. Not with gritty George Schuster behind the wheel.

The Thomas Flyer, built by the E.R. Thomas Motor Company of Buffalo, New York, is the latest automobile featured in Up Close, the Historic Vehicle Association’s text-based, story-telling video series about vehicles in the National Historic Vehicle Register. And what a story it has to tell.

Entrants in the 1908 race, held long before there were interstate highways—or, in many areas, any roads at all—dealt with snow, sleet, mud, mapless navigation, breakdowns, river crossings (without the benefit of bridges), steamship travel, and the threat of wild animals and bandits, which is why Schuster carried a 32-caliber pistol. Most of all, the cars and their teams battled public perception; most thought such a feat was not only inconceivable but impossible … until it wasn’t.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

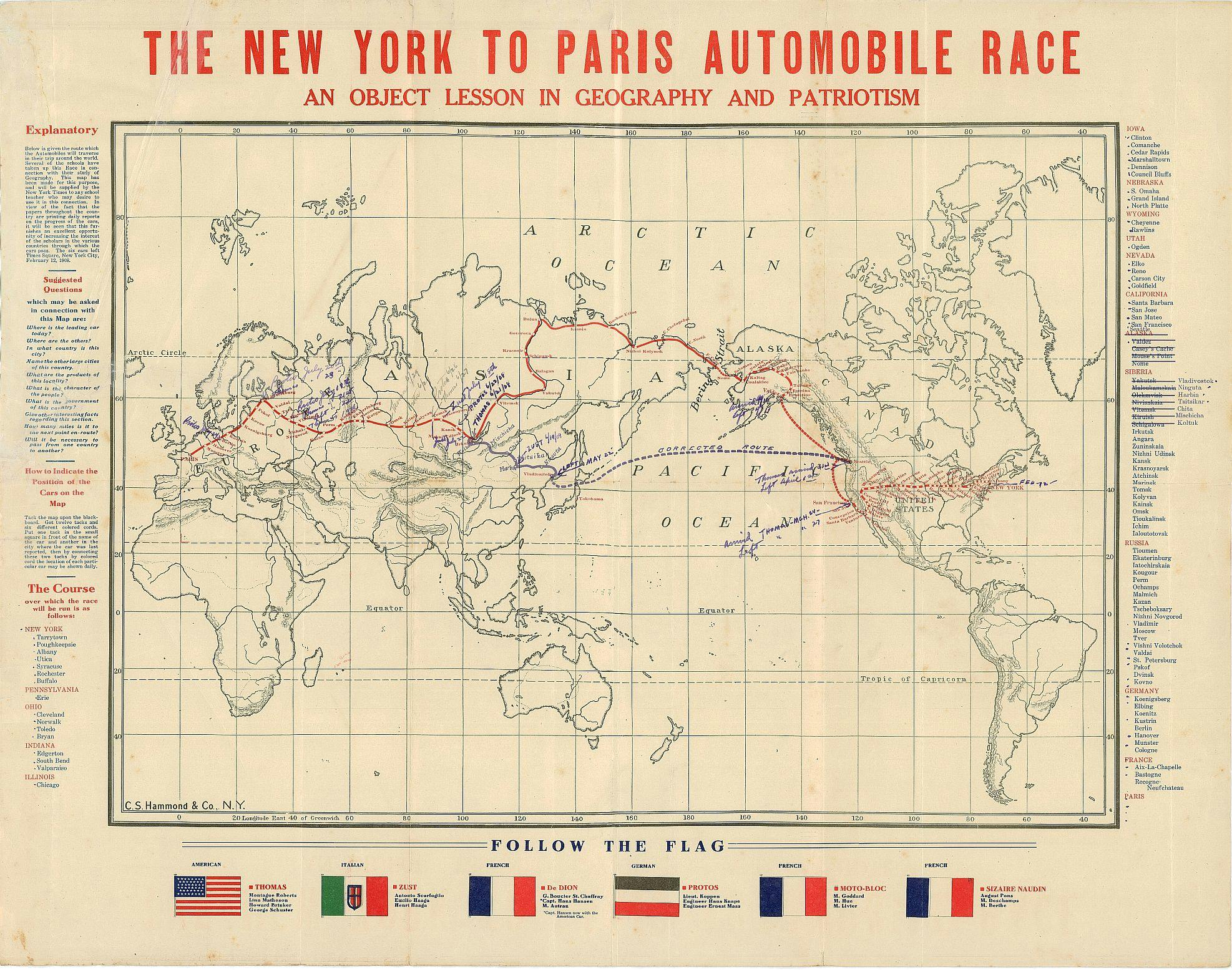

Starting in Times Square on February 12, 1908, and guided mostly by the stars and a sextant, the Flyer completed the race in 169 days, reaching the Eiffel Tower at 6 p.m. on July 30. The only American entry—and the only production car in the field of six—it would have finished earlier if Schuster hadn’t been stopped by a Parisian policeman for a faulty headlight, a problem Schuster solved by borrowing a bicycle light.

The American car was actually the third to finish, but Schuster was awarded bonus days because he took a longer route. The original plan was for competitors to cross the Arctic ice from Alaska to Russia, but that was scrapped due to heavy snow. By then, the field had already been cut in half. The Flyer—first to the checkpoint in Valdez, Alaska—was loaded onto a ship there so it could continue along the original route; the other two teams sailed to Russia via Seattle and Japan, shortening their trip.

The Flyer’s astonishing victory earned the team a trophy and $1000 cash from The New York Times and Le Matin newspapers, a sum that didn’t even cover expenses. Most importantly, the victory brought fame and put both man and machine in the history books.

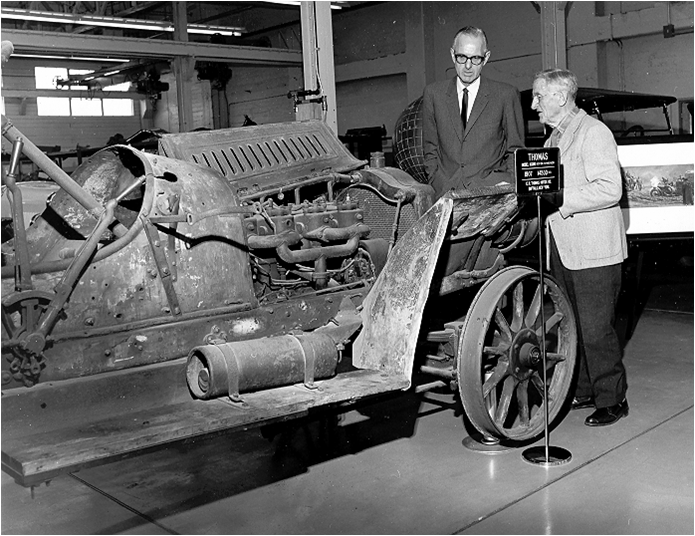

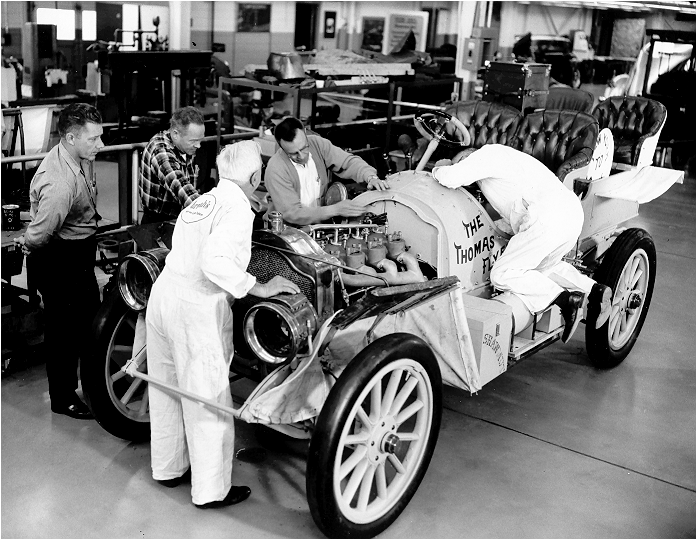

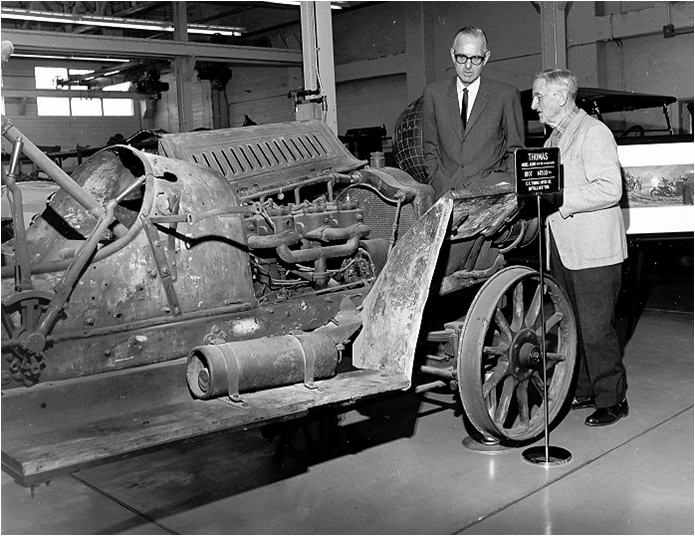

Schuster, the only member of the Thomas team present for every bit of the 22,000-mile journey, was also the only one to live into the 1960s. So, when hotelier Bill Harrah purchased the dilapidated Thomas Flyer in 1963, it was Schuster who verified that the car was authentic, pointing out a cracked frame that he fixed with a piece of steel from a Russian steam train. Harrah wanted to preserve the historic car and had it restored to how it appeared at the end of 1908 race—with the assistance of prop designers from the Walt Disney Company.

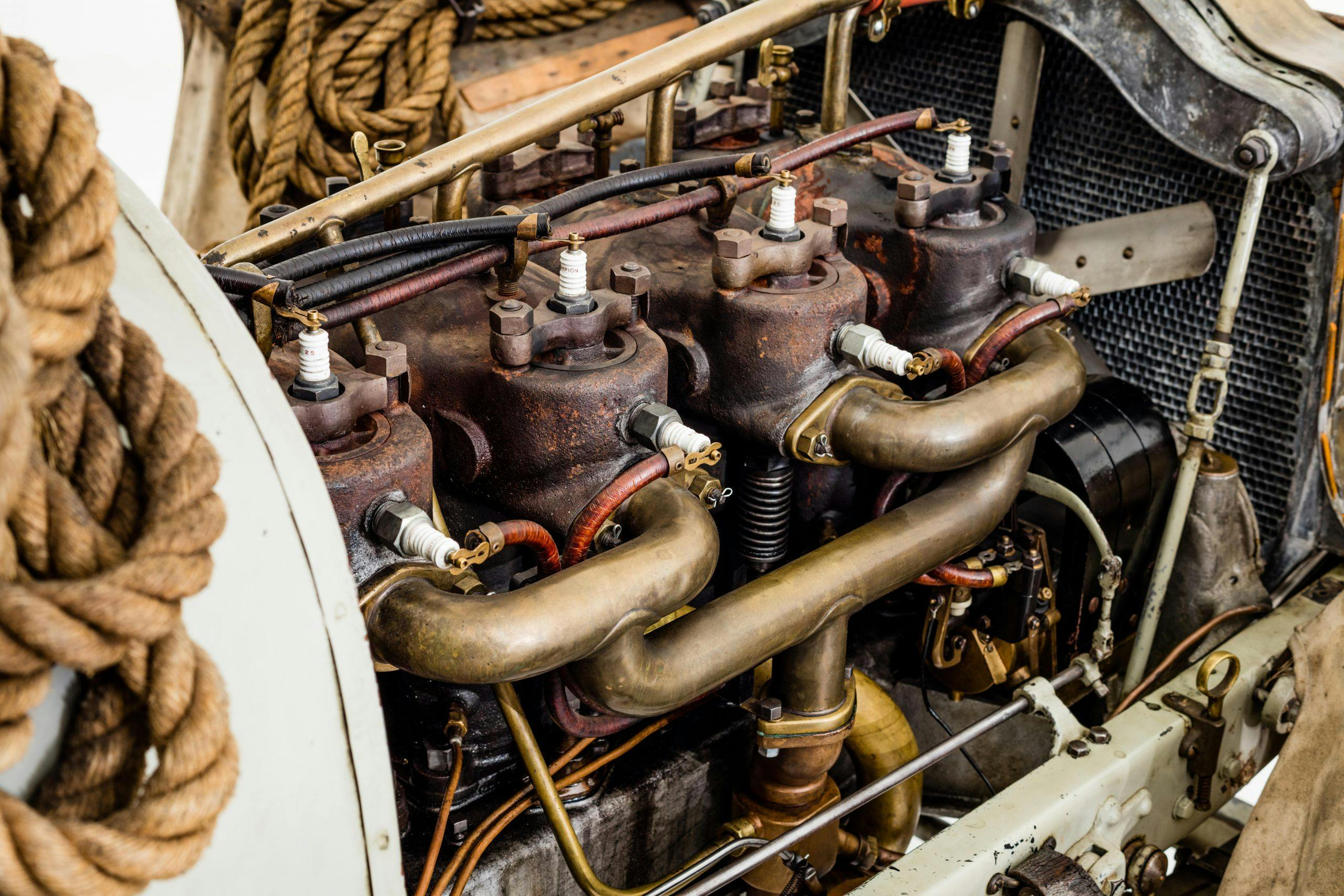

The Thomas Flyer is powered by 522.7-cubic-inch, four-cylinder, T-head engine that produces 60 hp. Using a four-speed gearbox, it is propelled by a chain drive that requires a near-continuous stream of oil, administered via a funnel mounted to the side of the front seat. In addition, the engine’s partial loss oil system is pumped by the driver (or his sidekick mechanic), sending oil to engine via brass distribution box on the cowl. Prior to the 1908 race, extra gasoline tanks were added to increase the fuel capacity to 125 gallons.

Schuster and the team asked people they met along the way to carve their names into the seat and on the Flyer’s wooden fenders. Seven different languages are represented. The car seated four, providing plenty of room for a driver, mechanic, and any journalists who might want to ride along.

In 2016, the Thomas Flyer—which resides at the National Automobile Museum in Reno, Nevada—became the 12th vehicle added to the National Historic Vehicle Register.

As for Schuster, there is no record of him winning another race of any kind. He died in 1972 at the age of 99.

Keep watching the HVA’s Up Close series, as new videos are released every Wednesday. We’ll keep you posted about new episodes, and you can also stay in the loop by following the HVA on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube.