Media | Articles

What does a $200,000 vintage Land Rover feel like?

In late-1940s Britain, Rover general manager Spencer Wilks tasked the company’s chief engineer, his brother Maurice, to develop a vehicle that could lift the company from obsolescence. Once a manufacturer of cars for the well-to-do, Rover was in a period of transition. During World War II, its manufacturing facilities had been turned into “shadow factories,” secretly producing important aircraft components. When hostilities ended, the worldwide demand for luxury vehicles was a fraction of what it had been before the war, and Rover needed a new strategy.

The Wilks’ answer was a sensible vehicle aimed at farmers, deliverymen, and light industry. A machine for navigating bombed-out roads, to help get the country back on its feet.

The immediate postwar years were a time of shortages. Most British steel of the era had been diverted for the production of ships and tanks. At the opposite end of the metallurgy spectrum, aluminum had become vastly important, needed for aviation components. Early in the war, Germany had great success in using submarines to slow the volume of transatlantic shipping. As hostilities churned on, however, Allied cargo ships sought safety in numbers, banding together in vast, escorted fleets called convoys. As more and more of those convoys made it to England, large alloy mills in the southern United States were better able to support Britain’s wartime demand. By the time the last bombs had dropped, an aluminum surplus had accumulated, and much of it sat in Rover’s factories.

There was another critical and unexpected surplus: American military Jeeps. Before the war, Britain had the largest mechanized army in the world. But in 1940, a series of military blunders and the disastrous Battle of France destroyed some 60,000 British land vehicles. America and England entered into a lease agreement that saw the former sending more than 80,000 Jeeps across the Atlantic, where many remained after the war.

The Wilks brothers’ first prototype was built atop the box-frame chassis and axles of one such Jeep, with body panels of surplus aviation aluminum. Color choices were limited to airplane-cockpit dark green and two lighter shades of the same color. Near the end of 1947, a fleet of early production models were tooling around the midlands for testing.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

By 1948, Rover’s new “Land-Rover” had a name: Series I.

The Series I was originally a stopgap vehicle, meant to inject new life and capital into the staid Rover brand. After the company blew through its surplus of aluminum and drab paint, the thinking went, its factories would triumphantly return to the manufacture of saloon cars.

Except they didn’t. The Series I became a massive hit.

For the next decade, Rover rolled out a series of new features on the model, all intended to make that very utilitarian vehicle more inviting for a human being. Heat, an actual roof, and windshield wipers all became standard. A longer-framed “station wagon” variant was fit for families and commercial use. In 1958, the Land Rover Series II debuted, featuring the breed’s first styling changes—a wheelbase widened for stability begat a new midsection, and hardtops received rounded upper rear windows that would evolve into the leaky “Alpine” windows found on Land Rovers for generations. In 1961, the Series IIA arrived, bringing new engine choices and small cosmetic updates.

If all of the above felt like an unsolicited history lesson, that’s because it was. At least for me.

As a Land Rover enthusiast and current and former owner of numerous pre-2008 Discoverys and Range Rovers, I’m ashamed to say I knew none of this. I could blame my historical apathy on the brand’s confusing nomenclature, which includes an era when Land-Rovers were Rovers but not Land Rovers (the hyphen was fired in 1978), or the convoluted ownership tree of England’s many carmakers, which to this day leaves me unable to distinguish an MG from any other Anglian sports car of the last half-century.

Really, though, it probably has something to do with how, in America, we rarely take the time to consider how our shiny new things came to be. Especially when something old has been made fashionable and new again.

My opportunity, history lesson, and experience came via an invite from Greg Shondel, president and cofounder of Himalaya, a Charleston, South Carolina firm that specializes in the restoration and customization of Land Rover Defenders and Series models. Shondel was eager to introduce Himalaya’s latest completed restomod project, a client-ordered 1967 Series IIA featuring an updated powertrain and modern comforts.

The name rang a bell. I had become somewhat familiar with the brand through Instagram, where a creepily accurate algorithm had presented Himalaya to me via “Reels,” the latest distraction that people my age mindlessly scroll through in bed when we should absolutely be attempting to sleep.

Himalaya was not originally owned by the Shondel brothers—the company began life as a design firm that specialized in restorations and outsourced most physical work. Greg and his brother James eventually acquired the firm as a passion project. The acquisition was prompted after the pair restored a right-hand-drive Defender together and found themselves in the middle of a booming market for vintage SUVs. The parts and supply-chain relationships established during their restoration, they realized, could underpin a business model for building more trucks.

Early on, Greg and James aimed to complete five builds per year, with all restoration work done under one roof by a single team of craftsmen. After a few years, Himalaya’s roof grew significantly larger, the company moving into its current 16,000-square-foot shop. It now turns out around 30 completed trucks annually.

Each client arrives with an outline of what they want, and the Shondels’ entire team comes together to help fill in the blanks. With engine packages including GM’s popular LT/LS V-8s and a variety of diesel (Cummins) options, Himalaya offers a veritable “choose your own adventure” of power, including turbo- and supercharging.

When I arrived, the shop’s house upholsterer was busy putting together a set of custom seats with tweed accent panels and matching leather, while simultaneously working on a solution for a client who had expressed worry that the white leather in her soon-to-be-completed Defender would fall victim to the markers, ketchup, and general child-disgustingness of her six grandchildren. (The solution was a new, marine-grade synthetic with the look and feel of leather but toddler-proof durability.)

One space over on the floor, a Cummins-powered Defender project sat awaiting the completion of its wiring. A quirk of scheduling meant that every Defender build in the facility was incomplete, so my driving experience was unfortunately limited to the restored Series trucks at hand.

Like Rover in the 1940s, Himalaya has its own stockpile of aluminum, albeit in salvage condition. The company’s boneyard is what keeps production moving, a fascinating collection of confidentially unsheltered and multi-generational old Rovers waiting to be brought back to life.

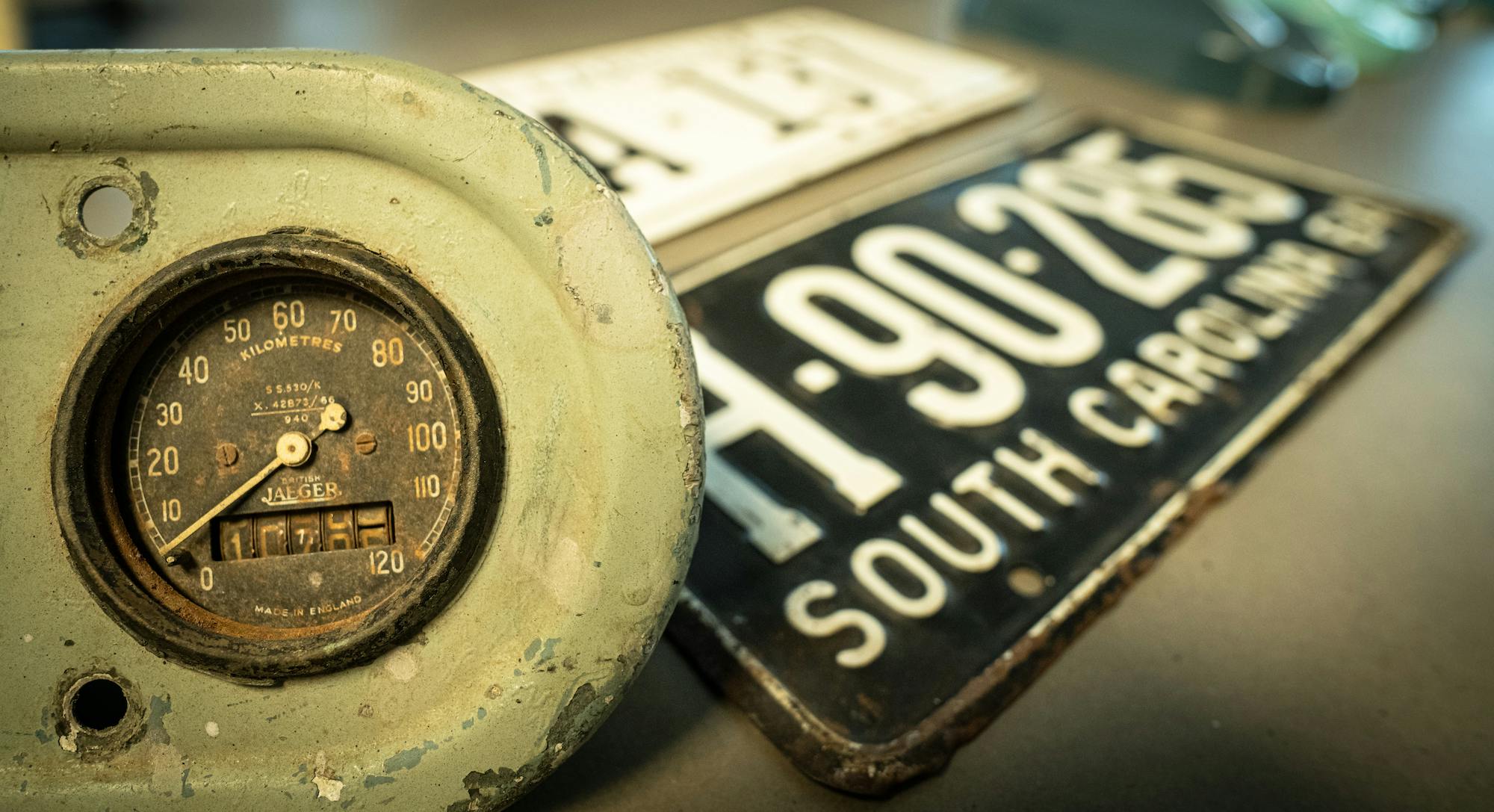

Robert Howard, Himalaya’s head of production, is the company’s direct line for that boneyard and for countless hard-to-find parts. Hailing from the English village of Redditch, Rob came on board after Himalaya merged with his own Land Rover restoration firm, Astwood. Redditch, he said, is a place where “you can’t look left or right without seeing a Land Rover of some type,” and that connection gives Himalaya direct access into Britain’s network of forgotten barns and salvage yards. Rovers affixed with snowplows, ambulances, ex-military vehicles—no truck is off the table, and Rob knows where to find them. After being packed into shipping containers, Rob’s finds eventually make their way across the Atlantic, where they’re meticulously inspected by United States customs officials before being shipped to the low country.

It was a chilly and gray day in Charleston, maybe 50 degrees Fahrenheit, a Midlandesque morning. The remains of an overnight rain dappled the roads. Fittingly, my first drive came in the form of a beautiful and unrestored 1968 Series IIA model that Himalaya considers its “shop truck.” That machine would serve as a stock reference for the recently finished restomod I would drive later.

This was my first time in a Series truck, and my only expectations came from a brief conversation with my own Land Rover mechanic. Do not, he told me, “get too excited.”

The ’68 was classic Series green. Everything had a feel, a smell, a texture. Bodywork imperfections were common—Series trucks were meant as working vehicles from day one, rarely fussed over on the line—and the paint’s smooth topcoat made the flaws seem like features. The doors closed differently each time, and the visibility-impeding, hood-mounted spare tire somehow seemed like an absolute necessity.

Slipping out of the Himalaya garage took a little finesse. The pedals felt loose by design, and the clutch pedal gave only a few inches of engagement. Brakes and steering were all on me, unassisted, and if there was any rain, I’d be at the mercy of an original set of visibly branded Lucas electric windshield wipers. To their credit, they worked pretty well.

Once on the road, the optional hard top, luxurious for its day, did its best to keep out the damp and chilly morning air. A little burning oil, a touch of clutch smell, some rattles—all things you’d expect in a half-century-old truck basically designed to be a tractor. The non-synchronized transmission ruled out imprecise downshifts, and finding the correct gear was a matter of maybe two or three tries.

As an owner of classic cars since I was a teenager, this sensory feedback is something I’ve come to appreciate and really enjoy. This site is no stranger to the subject: you and a vehicle, actively working together to get where you’re going, a partnership that gives no allowance for cell-phone time or troubleshooting Bluetooth. There is absolutely a time and a place for a quiet, comfortable, and computer-assisted conveyance, but with a rig like this, you drive simply because you enjoy it.

A surprisingly small amount of time passed before many of the Rover’s cues felt normal. Braking a little early, putting a little more effort into tighter steering situations, settling into a driver’s seat that initially felt uncomfortably close to oncoming traffic—along with the stereotypically British weather, it was easy to see how saloon-car owners in 1960s England would have found this new driving experience refreshing, challenging, and quite charming.

To me, it was perfect. Sitting high in the driver’s seat, I felt like a tradesman on the way to mend a tractor in the Cotswolds or do some sheep-shearing in Chipping Norton. Granted, this may or may not have been neurologically influenced by the petrol fumes making their way into the interior.

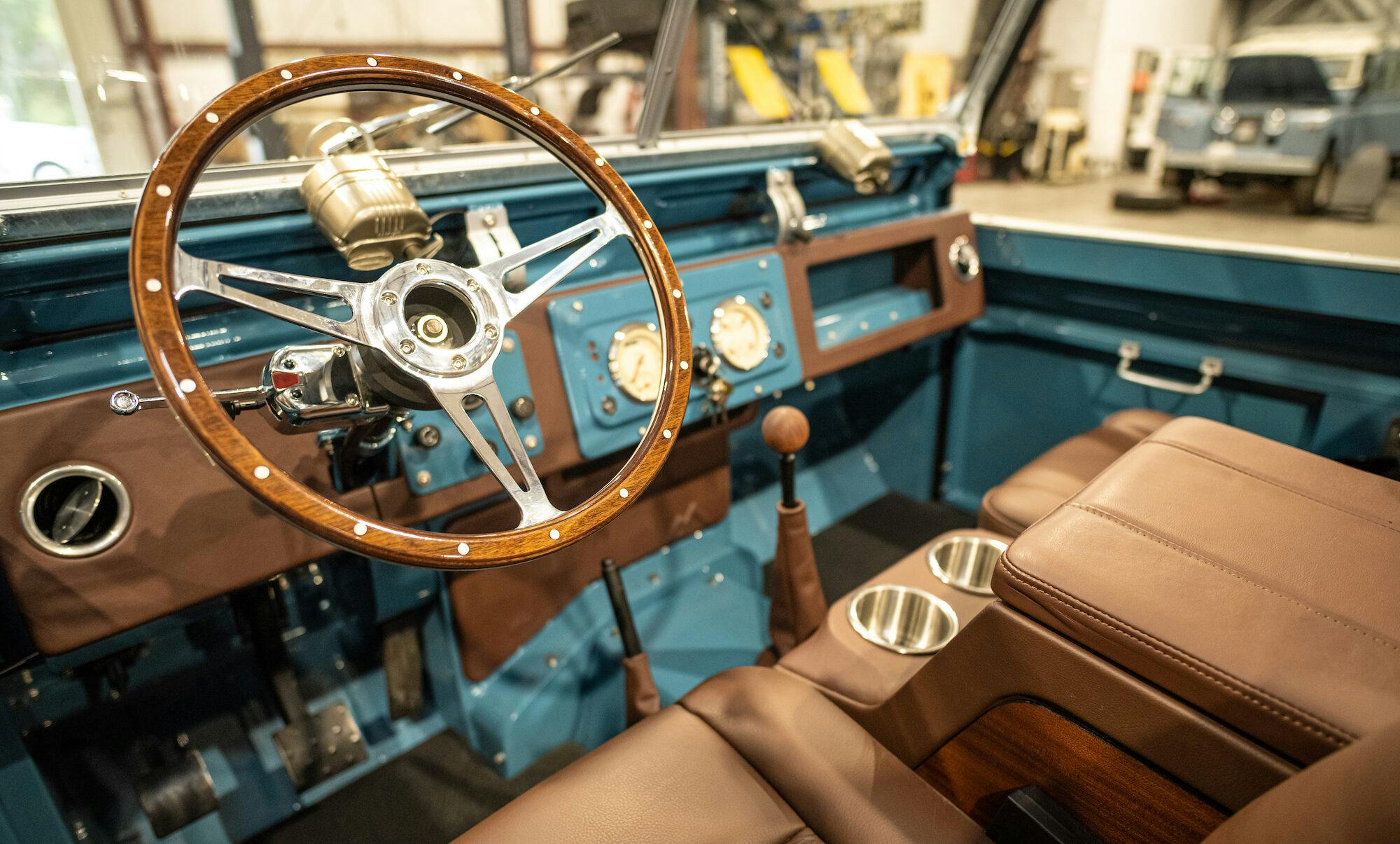

After my baseline drive in the late 1960s, I slipped into the present with what Shondel believes is the future of Himalaya—a modern take on the Series IIA. As with all Himalaya builds, the truck’s design plan was outlined through customer input.

Every angle featured a utilitarian throwback detail from Rover’s early days. Original cone-shaped front turn signals, accurately recreated bumpers, even the retained under-windshield vents, functionally simple and charming, they all suggest that customer familiarity with Series II lore impacted the truck’s final form.

The first suggestion that this IIA was different came in the subtle, sealed-beam LED headlights and teak-lined cargo area. Before its current restoration, the ’68’s body was finished in a limestone shade, a tone kept alive on the new wheels. With a nod to the original Series I engineering strategy, the rig now uses the wider axles from a Defender for stability, while a custom Brembo brake system makes stopping less dramatic. Under the hood is a tightly yet neatly fitted General Motors LS3 V-8 mated to a five-speed manual.

In the interior, a cleverly hidden air-conditioning system supplants Land Rover’s original speed-regulated ventilation, while a Bluetooth audio interface and push-button start are neatly integrated into the dashboard.

The sensations were similar to those of the shop truck, but the feedback was more engineered. The doors closed solidly and consistently but with the same sound. There was subtle engine vibration and gearshift feedback at startup, just without the worrisome rattles and smells. The transmission allowed for confident downshifts, which begat a gravely gurgle—a lovely reminder of the 6.7-liter just on the other side of that hard-to-find aluminum bulkhead.

On the road, Himalaya’s new IIA was comfortable yet still required my full attention for shifting and making good decisions with that LS3. Zipping up onramps into busy Charleston traffic was fun and effortless, and the IIA’s updated suspension had no qualms with a quick lane change prompted by another driver’s cell-phone fixation. It’s easy to imagine a truck like this thriving in a larger city, among tight parking spots, unforgiving curbs, and indifferently maintained metropolitan roads.

Mixed in with a feeling of renewal and modernity were some reminders that no old Land Rover was designed to hold your hand. The side mirrors sat in their original location, far away on the front fenders. Adjustments required a few trips back and forth from the driver’s seat or good communication with a passenger. The center-mounted modern gauges weren’t easy to read at first glance, as the speedometer’s chrome bezel impeded my view of the needle at lower speeds. Safety equipment was best described as historically accurate.

I mentioned my silly mirror gripe to Greg Shondel and his design team. They felt confident the mirrors could be mechanized if requested. If, you know, you’re that kind of person.

At drive’s end, none of my personal grievances trumped the feeling of someone taking photos of a car I was driving while I sat a stoplight, or an excited kid yelling out, “Mommy, look at that cool Jeep!” A reaction, I imagine, shared by kids in 1960s Britain.

One of the things I tried to keep in mind during my drive was how that ’68 was one person’s very specific vision brought to life by many people—the design and functionality choices did not have to line up with the ones I would have made. With interest in restomodding seemingly at an all-time high, the newly popular online slogan “respect all builds” should also include respecting the proper execution of the original concept. Himalaya’s work does just that.

A similarly appointed custom IIA from Himalaya will run you from $175,000 to $225,000. If you’re a purist and prefer the originality of a frame-off stock restoration, $150,000 will get you your own IIA in whichever shade of aircraft green you desire. A modern drivetrain in a long-wheelbase Himalaya 110 wagon will be around $300,000, with the firm’s priciest and most customized truck rolling out of the shop at $400,000. To get the historically accurate IIA experience, ask for a gasoline-scented air freshener.

In a market where a carbureted Ford Bronco from the early 1970s can easily command $230,000 on that website where you have to provide your own trailer, Himalaya’s IIA offers a comparatively priced option; setting aside the obvious Ford-Land Rover differences, much of the appeal here is in the bond-building fun of having intimate control of the design process. Your ideas begin with a vehicle that, for many, has more charm, history, and rarity than any currently trending classic American SUV. On top of that, a Series IIA is a timeless shape almost impossible to ruin.

It remains to be seen if Land Rover’s recent success with its new throwback Defender—and how car enthusiasts tend to obsess over past designs—will embolden JLR to consider a Series-truck revival. If I were an enthusiast with the means and desire to procure a restored or restomodded Series II, though, I’d absolutely pull the trigger now, while the supply chain for aluminum Rovers is strong.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

What is it about a box with wheels that is so appealing to me. I makes zero sense…and yet, I love that blue one!

I have and fj40 and i can spend 20 minutes just listening to the sound of the door opening and closing. Makes no sense

I spent 2 years in the back country of Jamaica in the late 1960’s, and had the experience of getting around in several Land Rovers. They were … primitive. Kind of like a tractor that had somehow escaped the farm and was playing in traffic. Maybe the aching in my neck that I have had for decades now came from the wrenching it took bounding back and forth as we hurtled along single lane, very rough roads at 22 mph. One Rover hurdled off a sharp cliff edge curve and lodged in the top of a mango tree, but it was lifted out with a crane and carried on.

Also, Lucas electrics do not pair well with the concept of a heavy-duty off road vehicle.

$200K is a heck of a premium to pay for Style – I guess that term can be applied here – or, perhaps, Posing, though that’s a rather negative assessment. It’s nevertheless amusing what people of means will pay for Landies, Broncos, & etc. And it’s pretty cool that some shops can actually make those crude old crocks driveable. I recall driving a buddy’s 1st-gen Bronco back in the ’70s, and while it was amusing at times, I couldn’t wait to hand it back to him.

Land Rovers have non-syncro transmissions??

I like them but I don’t six figure love them no matter the guts in the resto-mods.

I have a love hate relationship with Land-Rover’s. I love to hate them. Growing up in rural England, you were almost certain to encounter a “leisurely” farmer driven, diesel fume belching banged up Landie acting as a moving (barely) roadblock on a single track road. They were cold in winter, hot in summer, gutless rattletraps, and often, simply in the frigging way.

Tougher than nails, and about as comfortable as a bed of said nails, they lacked any ride quality and handling was non existent. Farmers hated them too, because they were pigs to work on, and often needed working on. But, they could invariable be “coaxed” to complete another day’s work with the help of a screw driver, pliers, hammer and baling twine, and they loved them for that.

I have struggled, without success, to understand what the attraction is to Land-Rover Series trucks today, and why some people are prepared to part with hideous sums of money to give one pride of place in their driveway or car collection.

Now I love to hate Land-Rover’s because of my lack of ability to see the investment potential of all those I encountered and passed on decades ago, as worthless lumps of scrap metal. LOL.

I would certainly NOT part with the kind of money needed to buy a non running project these days, much less a restored or resto-mod truck like this Himalaya build.

I also wondered about synchromesh in the transmission. I owned a 1953 80″ SWB back in the UK and it certainly had synchro, although I can’t recall if that was on 1st gear as well. I imagine as the gearbox was from Rover that it had synchro. I’ve driven many Land Rovers including a Series II from UK to Africa and gear changes were easy. I thought I could drive a non-synchro until I tried a 1937 Austin 3 ton truck without synchro, then the double de-clutching had to be perfect or there was a lot of crunching of gears!

One item about the transmission that wasn’t discussed was the 4×4 drive system and the transfer box. The transfer box certainly was not synchro, but just a plain dog clutch. Engaging the low range gear was a delicate business, hopefully while stationary.