Media | Articles

This unpretentious U.K. machine shop has been making history—literally—for five decades

If you’ve spent an outrageous length of time staring at a beautifully machined footrest on a Ducati Panigale or lovingly unwrapped a set of Omega high-compression pistons for your Mini Cooper’s A-Series engine, then I invite you to join me on a tour of Crosthwaite & Gardiner. The company’s workshops in the small village of Buxted, Sussex, are a paradise on earth for those of us who love engineering and the tactile feel of superlative-quality machined parts. Or are fascinated by the idea of a steel billet being turned into a work of art.

There are not many companies like Crosthwaite & Gardiner. Founded by engineers Dick Crosthwaite and John Gardiner in the early 1960s and from 1969 based here at Hogge Farm, the company has built up a global reputation for its engineering skills and its ability to reverse-engineer extremely complicated parts and assemblies to breathtaking standards. If this sounds like hyperbole, then don’t take my word for it—just ask Audi.

C&W has worked on all of the existing Auto Union “Silver Arrows” and was commissioned by Audi to build from scratch seven replica Auto Unions. Mercedes-Benz, too, has come knocking at the farm’s door asking the company to build for it engines for its W125 prewar grand prix cars.

John Gardiner passed away in 2007 and Dick Crosthwaite is retired, but his son Oliver now runs the business. Not that Crosthwaite senior seems to understand the concept of retirement, because on all my visits to Hogge Farm he’s been busy messing around with his own projects or fettling one of the several classic cars that he and his son own.

You couldn’t successfully run a company like C&G without having a deep knowledge of engineering so it’s not surprising to hear that Ollie Crosthwaite served a tool-making apprenticeship. On that subject, Crosthwaite & Gardiner typically has around 30 staff, several of whom are apprentices working on the premises or attending college with regular stints of practical experience in Sussex. “Many of them come from Oxford Brookes University,” explains Crosthwaite, “and what impresses us enormously is how clever they are at programming our CNC machines [Computer Numerically Controlled] and working in CFD [Computational Fluid Dynamics].”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

These CNC machines are remarkable. A current job in progress is the manufacture of rotors for a supercharger. These have to be machined to tolerances of 8 thousandths of an inch which, Ollie Crosthwaite helpfully points out, is around 4 hairs’ width. Each two-lobe rotor is machined from a large billet of steel, at least 80 per cent of which will end up as swarf on the machine’s bed. A huge amount of machining time is required but this can go on overnight or even over a weekend. Sounds simple, but before this wizardry can take place a lot of traditional measuring and setup has to be performed.

“I love it when we take on a new challenge,” says Crosthwaite Jr. “Like these crankshafts that we’re making. They’re for a Porsche Carrera 2 engine; the double overhead-cam engine that was fitted to the 356 Carrera and several racing Porsches.” The crankshaft runs in roller bearings and therefore is split into several parts, each of which fits together and is positioned by a toothed face. “It’s really clever,” says Ollie, “as they’re self-aligning. It means that you have to machine a flat face between the teeth, which is a complicated job.”

Frustratingly, especially for the company itself, these days a lot of non-disclosure agreements have to be signed, so there are quite a lot of jobs in progress that are hush-hush. Even private clients have asked for them to be signed, presumably so that when the glorious unveiling of the car happens at Pebble Beach or some other prestigious event, the balloon hasn’t been popped earlier by news of its ongoing restoration. C&G also carry out full restorations, one of which is hidden from view in a secret workshop. It’s for an OEM that would get very grumpy indeed if word got out.

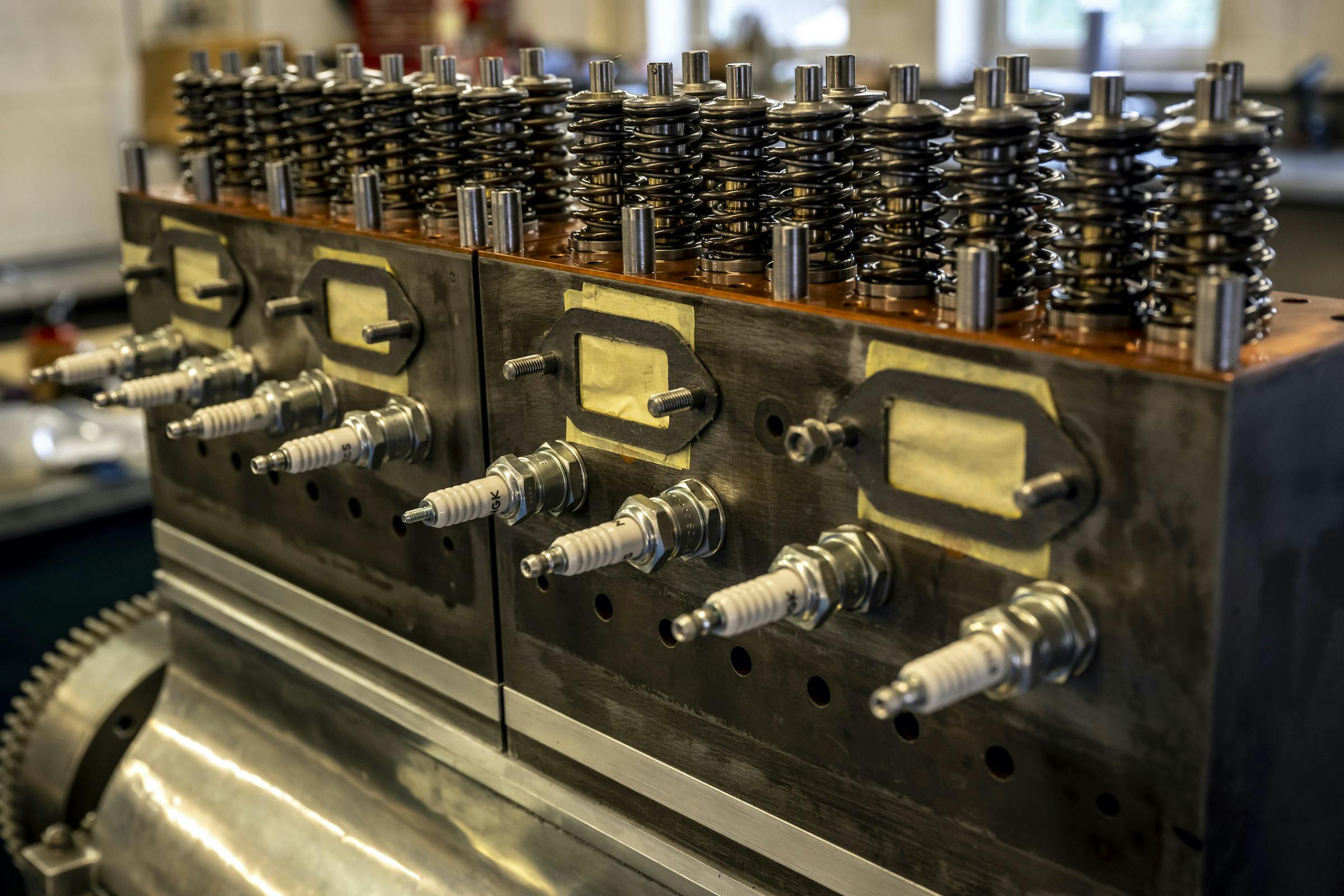

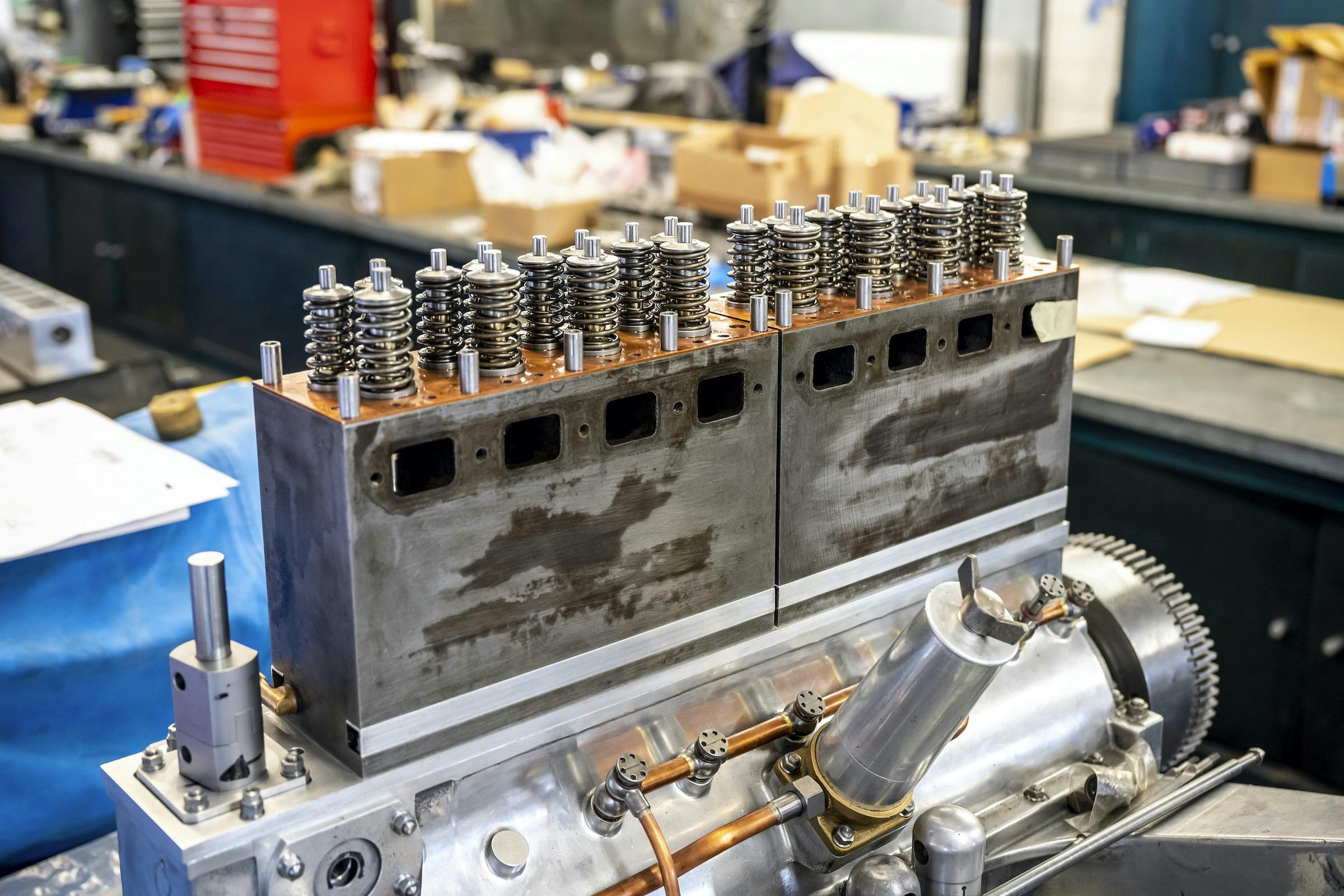

Going back to the Mercedes-Benz W125 engines that C&G has built, there are a few cylinder blocks sitting around awaiting completion. “Those engines are unbelievably complicated and contain some of the most stunning engineering. The straight-eight cylinder engine has two separate blocks of four cylinders, each of which is entirely fabricated. Sheet steel is shaped and then gas-brazed, and the cylinders themselves then welded to a thick steel plate that then bolts to the crankcase itself. We generally use exactly the same techniques as were used originally in the 1930s, but for that particular detail we use electron beam welding because it’s just better.”

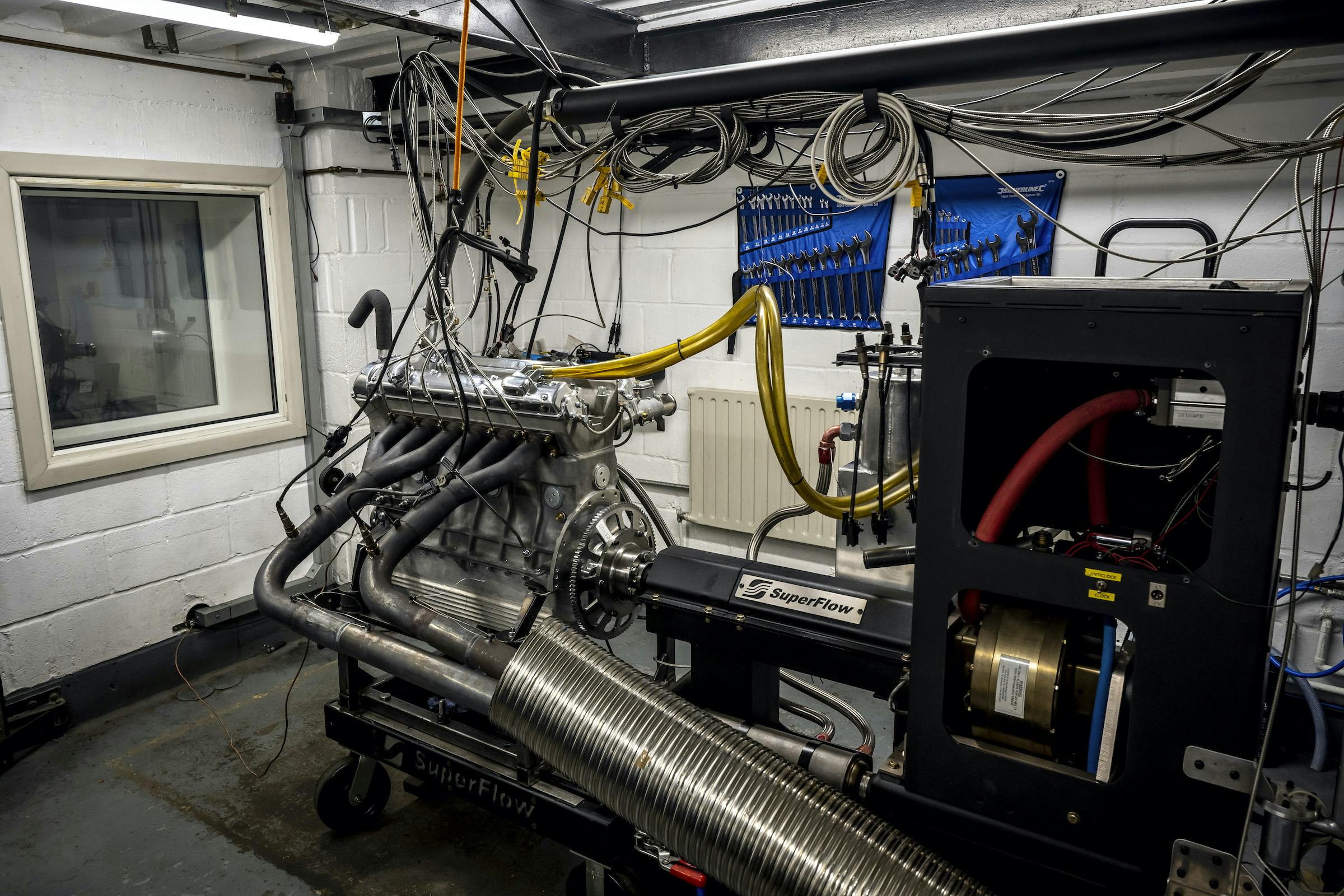

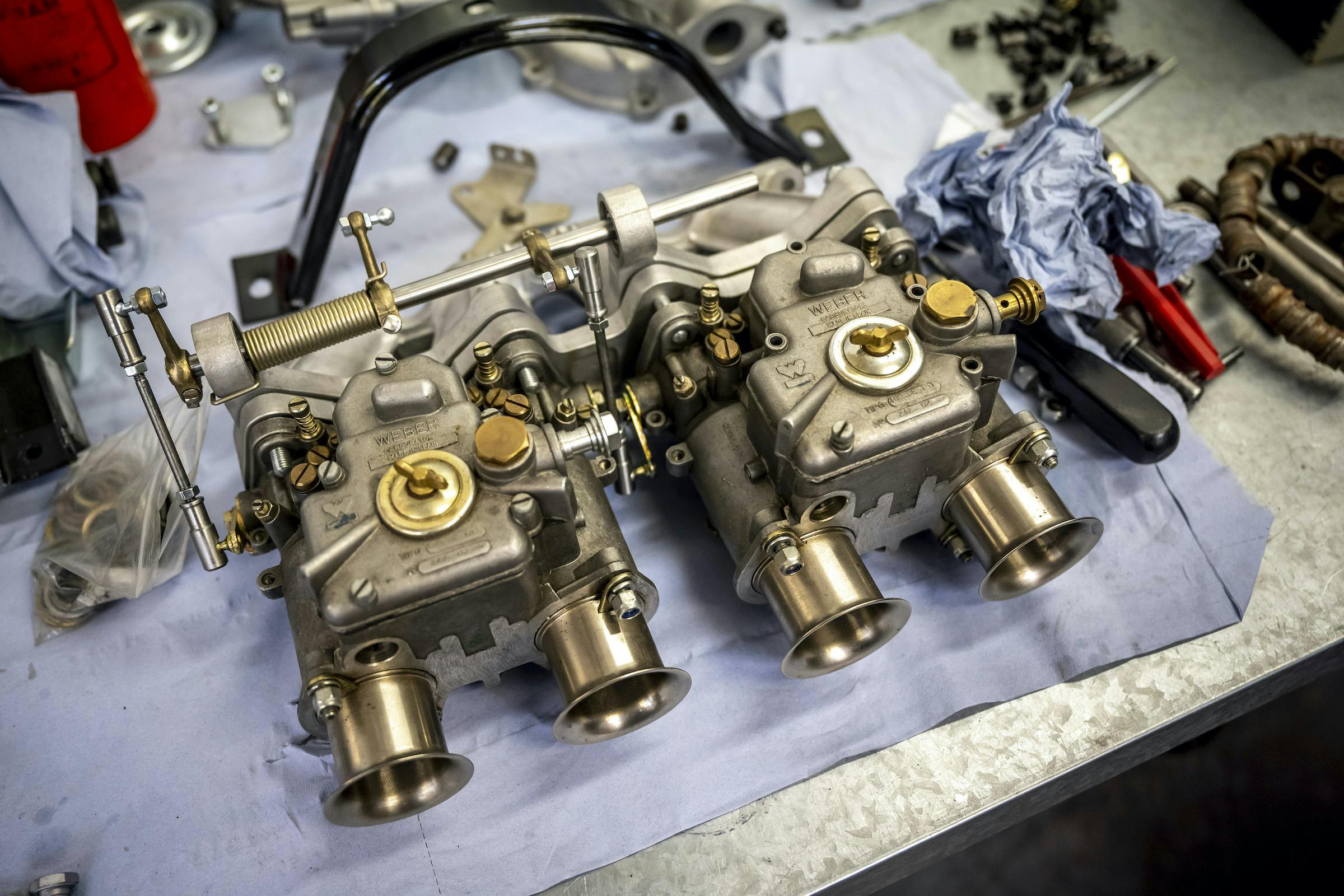

What is no secret is that Crosthwaite & Gardiner builds complete racing-specification Jaguar engines that feature aluminum blocks, used in many historic E-Type race cars. We’re in luck today because there’s a recently finished motor being run-in on one of the company’s dynamometers. This 3.8-liter unit is pumping out over 300 hp and with it a fabulous noise. “Our nearest neighbour, an elderly lady, says she loves the noise of the engines running up,” says Ollie, “but she’s not so keen when we run engines like the W125 because they burn methanol, which doesn’t smell particularly pleasant.”

The dyno controls, complete with computer screen, look very high-tech; what doesn’t is something that looks like an ear-trumpet or speaking tube from an ancient ship. “Actually,” explains Ollie, “it’s so that the guy operating the dyno can hear if there’s knock or pre-ignition. It’s much more reliable than using modern knock sensors in the block itself.”

You’ll be familiar with the problem: Got too much stuff for the garage, so build a bigger garage. Acquire more stuff and then need an even larger one. Crosthwaite & Gardiner has a similar issue, as its parts department is struggling to contain the massive selection of parts that the company makes and keeps in stock. It’s not only engine parts that are made here. Need a new magnesium rear wheel for your Porsche 917? They’re in stock. As are rear uprights for a Lotus 18 single-seater and myriad other parts that, miraculously, Oliver Crosthwaite can identify.

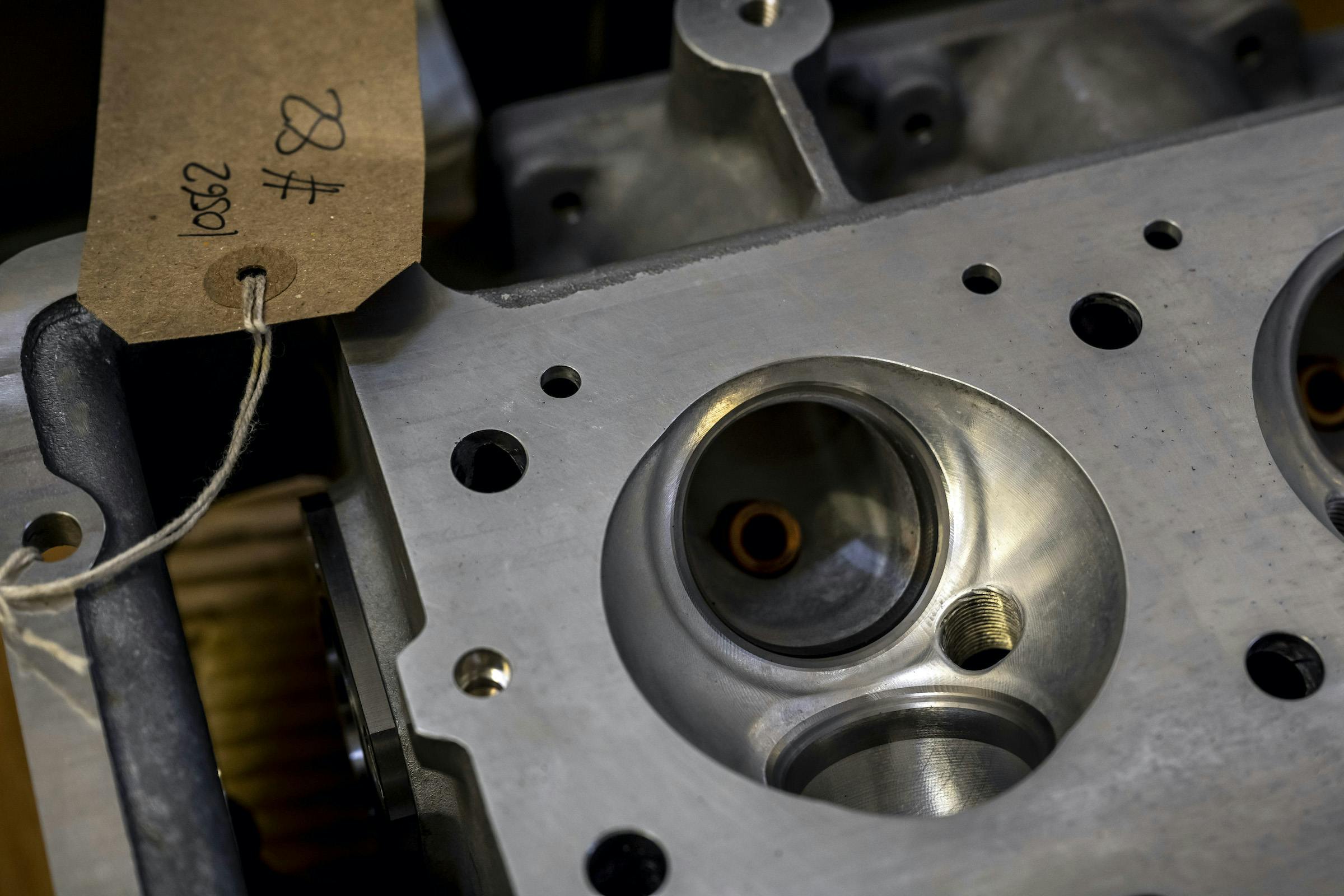

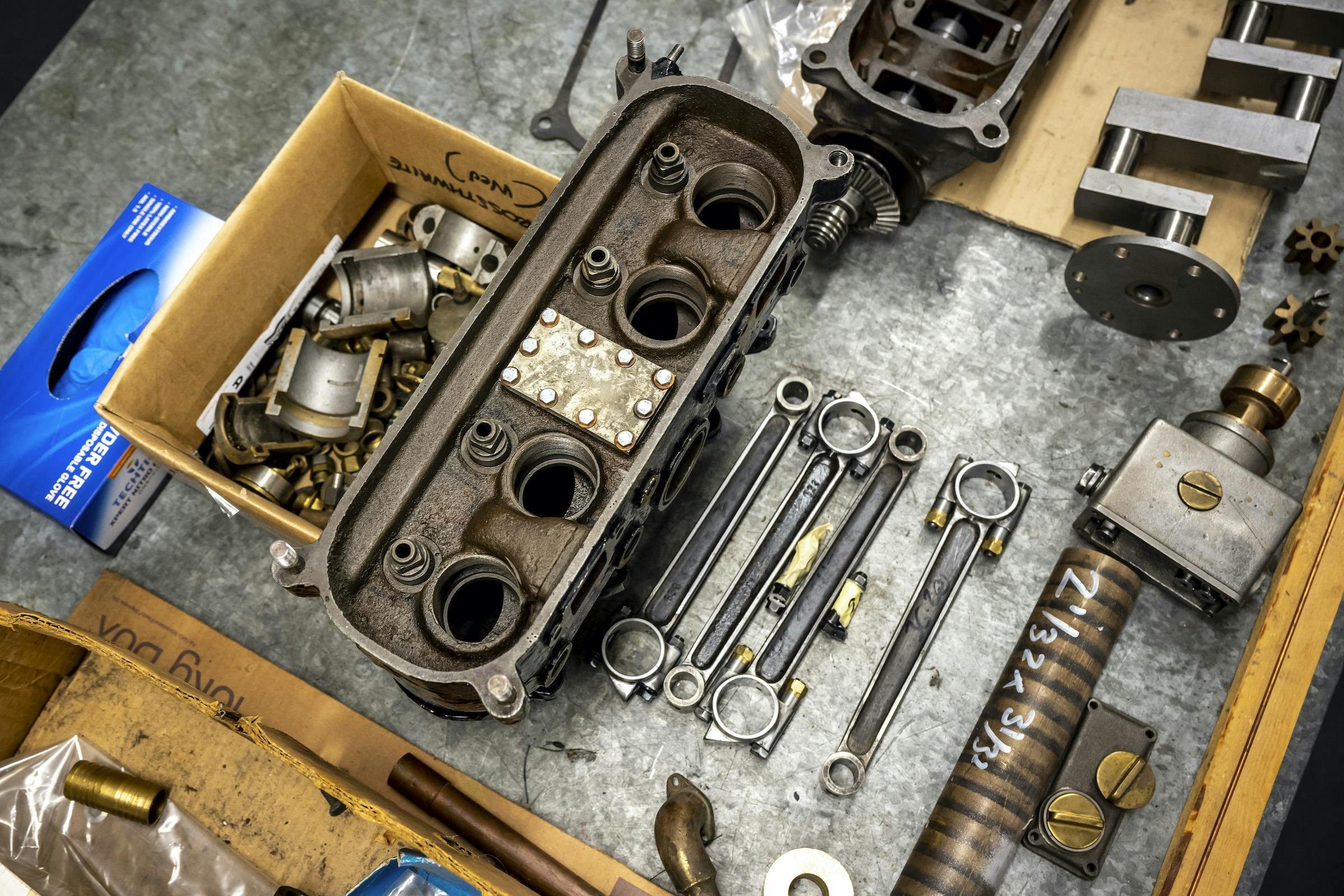

Sitting in a corridor on a pallet is a brand-new Coventry Climax four-cylinder racing engine. “These were the first complete engines that we built from the ground up,” says Crosthwaite. “We did the first one about 30 years ago and since then we’ve done about 150 cylinder blocks so that gives you an idea of how many complete engines we’ve made.

“We assemble the engines for customers but can also supply them as a kit of parts, like this one is, right down to the spark plugs. It saves the customer money but there’s still about 160 hours of labor required to assemble the engine. What the customer doesn’t need to worry about is details like lapping in valves or polishing or flowing ports, because the machining is so accurate that the valves don’t need lapping in; the ports are CNC-machined to a ready-to-go finish.” And, hold your breath, the price? “About £35,000 (~$48,400) for this 1.5-liter version.” Considering the value of the racing car it’s likely to be fitted to, this doesn’t strike me as exorbitant.

There are other examples of the company’s trusted craftsmanship. Imagine you’re just about to set off for a drive in your McLaren F1 when you hear an ominous squeal from the engine compartment: The water pump’s on the way out. What to do? Ring McLaren for a new one? No, because a company called Lanzante Motorsport is actually the go-to place for F1 servicing and repairs. Trouble is, BMW (which made the F1’s engine) doesn’t have any spares and worse still, junked the tooling for the pump. Fortunately Lanzante commissioned C&G to reverse-engineer the pump and make fresh dies for the pump’s major castings. Those dies are now stored along with hundreds of others, all carefully marked up in crates, for future needs. The last time I felt so in awe of history I was standing in the Cairo museum.

But what about the future of Crosthwaite & Gardiner? John Gardiner didn’t have children and Ollie Crosthwaite has one five-year-old daughter. Will there be a third generation at C&W? “It’s looking reasonably promising,” says a smiling Oliver. “We’ve got a replica baby Bugatti and she loves driving that. She also loves sitting in the various cars when I bring her in on Saturdays—the Frazer Nash is her favorite. More importantly she seems to really enjoy taking things apart and putting them together again.”

As for the company itself, I’m sure that it has a long future. Take the example of the McLaren F1 water pump. It’s possible that the tooling for say, a Bugatti Veyron water pump, could also be mislaid in a vast organization like the Volkswagen Group. Will even Ferrari keep all the tooling for cars like the F50 and Enzo?

“I’m sure you’re right,” says Crosthwaite. “Throughout its 50-year life the company has changed and adapted. The work we do today is very different from that we were doing even 10 years ago. I’m sure if you come back in another ten years then we’ll be concentrating in another area yet again but who knows what?

“One thing I can promise you is that we won’t be rewinding electric motors.”