Media | Articles

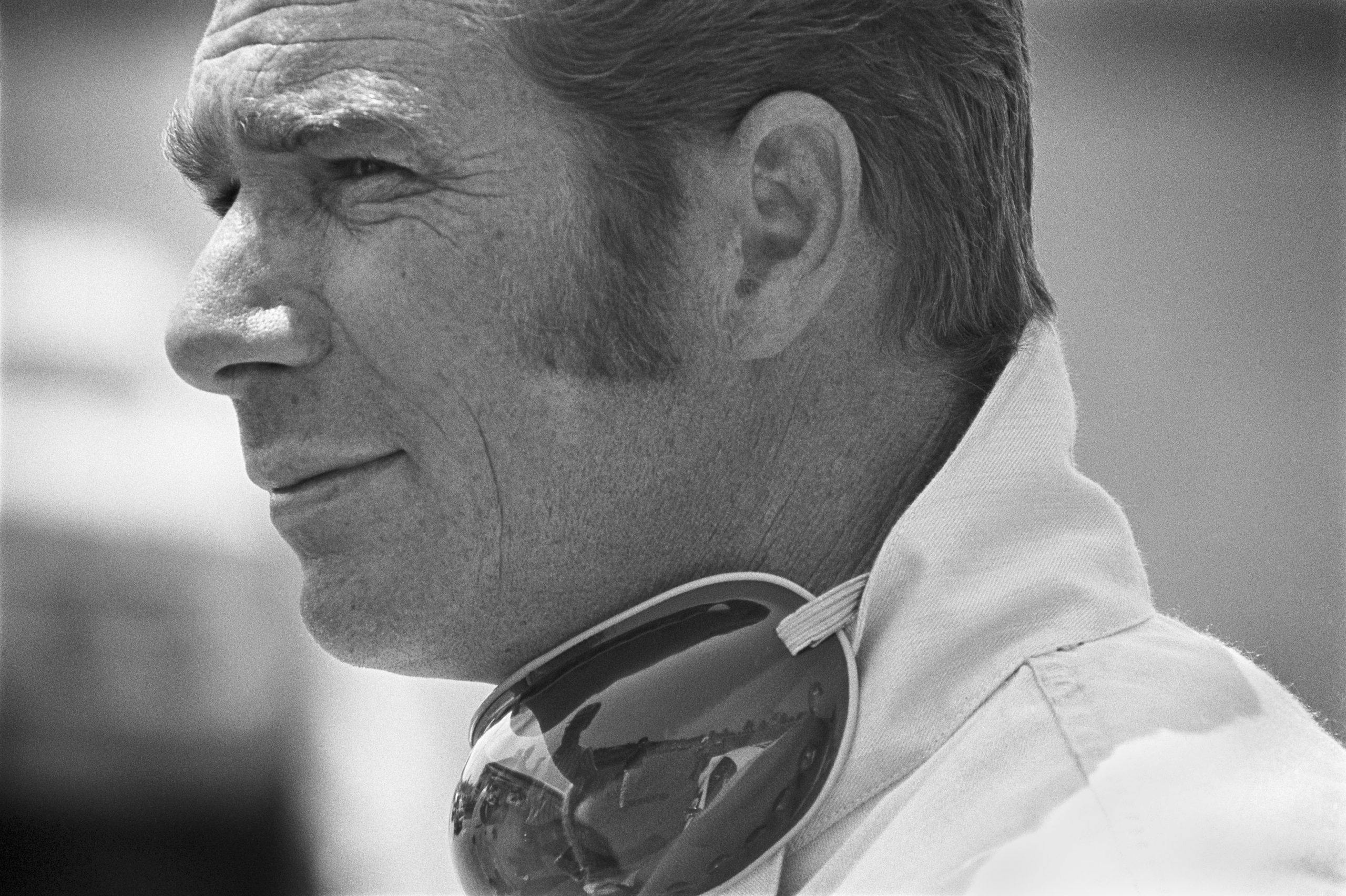

The Texas Trailblazer: In conversation with motorsport icon Jim Hall

Jim Hall’s list of accomplishments reads like that of man who, through sheer force of will, managed to eke out 25 hours of work per day. In fewer than two decades, the trailblazing Texan transformed the landscape of professional road racing, developed a technical alliance with General Motors, demolished numerous records, and even won an Indianapolis 500. He did this largely through his understanding of physics and, more specifically, aerodynamics. Hall pioneered several innovations used in modern, professional road racing, like suspension-mounted wings, in-cockpit adjustable aero, automatic transmissions, and aft-mounted radiators.

If Carroll Shelby was a hammer, Hall is a graphing calculator. In the mid-1950s, Hall studied engineering at the California Institute of Technology. There, he developed the skills and philosophies that he would apply to building race cars throughout his career. Fresh out of college, Hall worked with California-based race car builders Troutman and Barnes to fabricate Chaparral 1, a rolling work of art equally adept at beating Maseratis and Listers of the time. One year later, in 1962, with partner and fellow road racer Hap Sharp, Hall obtained the bird moniker from Troutman and Barnes to launch Chaparral Cars.

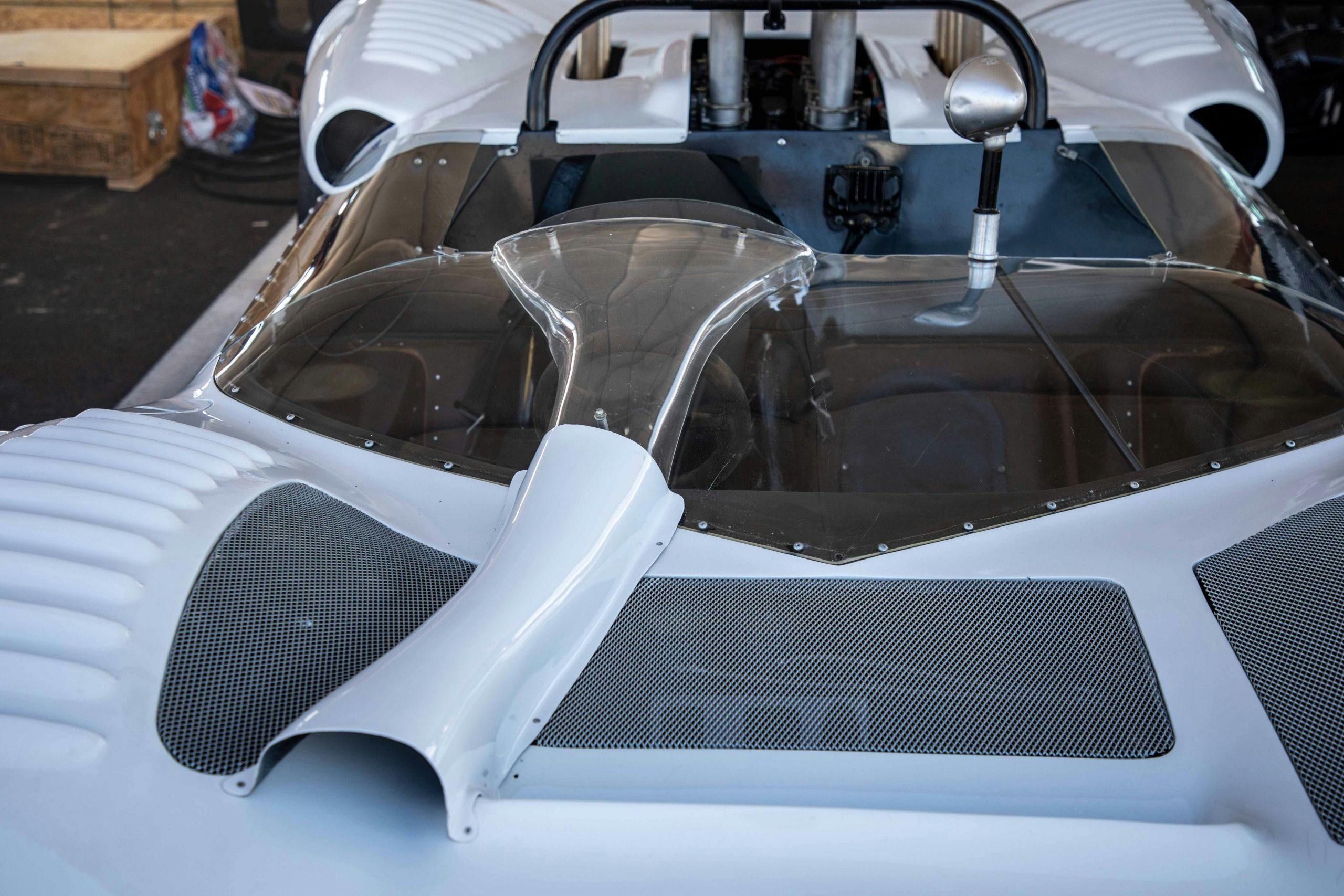

With Chaparral now a fully-fledged shop in Midland, Texas (and adjacent paved test course known at Rattlesnake Raceway), Hall and crew began work on their 2-series cars. Every 2-series road racer wore a coat of gloss white paint, featured a Chevrolet powerplant, and was breathtakingly fast. Each successive “2” built on the ideas of the last, and by 1970 Hall had worked his way through the alphabet to ‘J,’ from the Nurburgring-slaying 2D, to the Can-Am powerhouse 2E, to the big-block-powered 2F and beyond. Hall and his Chaparrals flourished during an era of innovation—and paper-thin rulebooks.

In the late 1970s Hall built 2K, an open-wheel Indy car that utilized ground effects to achieve incredible levels of grip. Naturally, the car won six out of the 27 races it entered, first in the hands of Al Unser Sr., then Johnny Rutherford, who notched the car’s greatest victory at the 1980 Indy 500.

Since then, Hall has slowed his pace and these days he enjoys a game of golf over 200-mph contests. To celebrate Chaparral’s 60th anniversary, the American Festival of Speed declared Chaparral the featured marque and invited Hall and his cars out to Pontiac, Michigan. Given the pandemic, the 86-year-old Hall stayed home while three of his cars, his son, and grandson made an appearance on track.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Though we couldn’t chat up Hall at the festival, we jumped at the opportunity to interview this motorsport’s icon over the phone. Two days before his cars graced M1’s course, my cell chimed—an incoming call from Midland, Texas. On the other end of the line, Jim Hall.

Hagerty: Thanks for the call, Mr. Hall. I have a couple questions for you. They’re not too hard hitting, I promise.

Jim Hall: I’m happy to do it. And you don’t have to softball with me. I’m pretty direct.

Thinking back to the onset of your career, what got you into racing? What was the spark? What happened?

Oh, it was really easy. I was interested in mechanical stuff and cars from the very beginning. I appropriated a Whizzer bike motor from my older brother when he went off to college. I attached it to my bicycle and fixed it up so I could ride it with that motor. Then, I built my first Soap Box Derby racer when I was 11.

My older brother Dick called me one day when I was home from Cal Tech. Maybe it was ’54 or ’55. He said, “Hey, we’re going down to Fort Sumner to run my Austin-Healey 100 in a sports car race. Do you want to go with us?” I said, “Sure!”

Dick had rheumatoid arthritis when he was a teenager, and it messed up his lower joints and eyesight a little bit, so he couldn’t really do some of the stuff he wanted to do. By the time novice practice came around, he said, “You want to get in and try it?”

It was an SCCA regional race at an airport. I put on a helmet and I didn’t go through tech. I just strapped on the helmet and got in it, drove it around. Nobody said anything. I had so much fun, and when it came around for the novice race, Dick said, “Well, go ahead and race it.”

The race went horribly. When I was coming down the back straight on the first lap, it smelled like gasoline. I pulled into the pits and fuel was all over the engine compartment. I just parked it. I was 19 and I was hooked.

Oh, you had the taste of it right then and there. You said it was a 100? So, a four-cylinder?

Yeah. The four cylinder one. All you did was lay the windshield down, put the belt on, and go.

Out of all the race cars that you’ve worked on, which one is your favorite? I imagine that’s really tough, like picking a favorite child.

Well, the car that I really am most proud of is the 2E, which is our Can-Am winged car. When we brought it out in 1966, it never was particularly successful. We had a lot of trouble with it, so you can’t say it was a great race car. I started with a clean sheet of paper, and I said, “I’m going to input everything that I know to improve this car and its aerodynamics.”

I think 2E is a fine racing machine in the sense that it’s very easy to drive and easy to set up. There are so many fine adjustments that the crew can adjust to make it work at any race track. You can make it handle predictably, so the driver knows what it’s going to do. That’s what makes them fast.

If the 2E is my favorite design, then the 2F is my most sophisticated design among the 2s. The 2F actually adjusts the aerodynamic download as speed changes to remain balanced over a broad speed range.

All the experimentation with aerodynamics, were you applying anything you had learned in Cal Tech in your formal schooling? Or were you just kind of winging it out there? Pardon the pun.

Well, I tried not to wing it too much. You end up taking some shots and doing some things that you don’t know the answer to, but I think my education gave me an advantage during that period of time. I got to where I recognized, early actually, right towards the end of 1963, that if you put a down-load on these cars, it really changed the performance potential. Then, if you managed it properly, you could make the car handle over a broad range so that the driver liked it not only at slow speeds, but at high speeds as well.

I was able to recognize issues from the driver’s seat. When something went wrong, I could go back to the desk and write the equations and say, “Now what happened there?” Once I started doing that, treating issues as I learned in school, that’s when I started really making some changes that were worthwhile. I think that got us ahead of the pack during the mid-’60s.

Was there any driver that you gelled with the most throughout your career?

Golly, I’ve been very fortunate to have such great people work for us. Phil Hill was really a lot of fun. He had a lot of experience and he’s a car guy. He understood what made them tick and how to preserve the cars throughout the race. For instance, we used a so-called automatic transmission that you had to shift without a clutch. It was like operating an old tractor. It was a dog gearbox, and so you had to match the engine speed in order to make it go fast. Most of the drivers who drove those cars tore up those dogs pretty quick and we’d be replacing them.

When Phil started driving for us, it was amazing. He could get the same performance without tearing it up, like I could. I thought that was really a tribute to Phil and his experience with the mechanical side of things.

Jackie Stewart, Johnny Rutherford, Gil de Ferran, Mike Spence, Vic Elford, Al Unser, and Patrick Tambay–I’ve got to say that I had an awful lot of nice people, tough, good drivers driving for me. Brian Redman, for instance. I mean, that guy’s a real racer and a nice, nice gentleman.

If you were to go back in time with what you know now, are there any big changes that you would make to your cars?

I tried to move forward with the science of the rae car at too quick of pace for us to do well. I may have been better off to slow down and build a car that would be more reliable. For instance, we should have maybe had 2C run an additional season rather than debuting the 2E in 1966.

That said, I did a decent job of collecting data. I started measuring the ride heights of the cars when I got interested in loading the car. My first gauge was on Chaparral 2. It lifted a lot, so I just wrapped a piece of welding rod around the upper wish bone and drilled a hole for it to stick up through the fender. Then I filed a notch at it where it was at zero (no load) and put some notches up the rod.

We had our Rattlesnake Raceway at that point, so I could run a hundred miles an hour down the straight, one hand on the wheel, another snapping a photo of the rod with my Polaroid camera. Then, while back at the shop, I loaded lead bags on it to see how much weight moved the car. It was time consuming, but I could do it because I was sitting right there on the track with my shop.

Wow, fascinating.

I also made a set of manometers–10 tubes filled with colored water mounted on the car where I could photograph it. I’d go out and make a run and I’d make one at 60 miles an hour. And then I’d make one at 100 miles an hour, and then 120 to find the lift curve.

It was really interesting to see what the pressures were on that body during that period of time. We had so much lift on that first Chaparral car that we had to build kind of a snowplow thing to go under the front of it.

During that era, what motivated you? Did you want to be fastest? Did you want to be most reliable? Did you want to be best handling? What were you looking for out of your cars?

I wanted enough reliability to win a race, for sure, but I’d have to say my focus was basically on building the fastest machine that I could build under the regulations that were imposed.

What sanctioning body or modern class today piques your interest? Or are there any?

Well, I have to admit that I’m lacking a little bit there, Cameron. I’d rather just get outside and play a little golf or something instead. I did it hard and heavy, for a lot of years. I was so excited about what I was doing that the hours didn’t make any difference to me and I was lucky enough to hire a bunch of guys that were enthusiasts like me.

It’s amazing how many hours I actually spent. When I did a Chaparral body, I’d worked till midnight on it out in the shop by myself or with Sandy, my wife. Then, I’d go in the morning I would finish paperwork in the office or test on the track while my employees smoothed-in my changes. During my youth, I could do that for days, with four or five hours of sleep per day.

It never felt like it was work. I just enjoyed what I was doing so much I couldn’t wait to build a next one.

Is there an innovation that you’re most proud of? Something that you incorporated on a car or something that you stayed up late until night and you got it?

Well, the one that was most important to me was beginning to understand vertical aerodynamic forces on cars. Back when I started, I had a partnership with GM and I got to see some of their wind tunnel stuff. At the time, they were really interested in interested in stability on highways, and they didn’t really look at the vertical forces. They were just looking at side force and drag.

I discovered in their wind tunnel, and through testing at Rattlesnake, that if you change the vertical forces a little bit on the car front to rear, that you could make it handle just the way you wanted. It’d be stable, nice to drive.

Speaking of General Motors, what was the relationship with GM when you were pumping out the white cars?

Well, it was a good one for both of us, really. One day, at Elkhart Lake, I walked over to the Corvette Corral and there was this really slick looking rear-engine coupe called the Corvair Monza. While I was walking around the car, GM designer Bill Mitchell walked up. After some talking, he invited me to Detroit, where I met other GM designers and engineers like Larry Shinoda, Frank Winchell, and Jim Musser. We quickly realized we had many of same interests.

At the time, GM was also facing lawsuits from people who crashed their Corvairs. Winchell asked me if I would be willing to do some test work on skid pads to educate some of the engineering professors around the country that they were going to have to use as expert witnesses.

I learned how to document some of this stuff better and learned about that. When I had a problem of my own, I’d call Frank sometimes, or Jim Musser and say, “How do you do this?” It just grew to the point where we had a pretty nice working relationship. They started coming down here to our property here in Texas, because they knew it was kind of out of the public eye and the weather was good.

What cars would General Motors bring down?

I decided we’d just go ahead and put the money in if they wanted to come down here and test them, so we built a skid pad. The Corvair, Ford Falcon, a Renault, and a Volkswagen. We ran all of them out to the limit, so that they could know how they handled through the whole range. They brought down CERV II, the sports car that Zora built, too.

The CERV showed us that all-wheel drive wasn’t worth carrying the extra weight around. Boy, that really saved me a lot of work because it showed me that wasn’t worth messing with in my race cars.

Did you have a favorite track?

You know, I did. It was Mosport in Ontario. It has some really good turns; some turns that change radius in the middle, some that go over a hump, and some that have a bottom in them that you can take at higher speed. There’s a real hairpin on the back, too. I really enjoyed driving that course. Our cars, particularly the 2E, when we finally got all that stuff on it, I could dial it in to where it was working on every corner. I mean, when you can go with full confidence, up to max-g and know that you’re not going to make a mistake. It’s really fun to drive one of those cars like that.

I can imagine. Well, thank you for taking the time to chat about your life and your cars. We really appreciate it.

You’re welcome. It was nice to be honored by the American Speed Festival, at M1 Concourse, and receive their Master of Motorsports award.