Media | Articles

Restoration and Performance Motorcars turned Ferrari enthusiasm into a family business

“It’s like dairy farming. It’s in my blood,” Steve Markowski says in a heavy New England accent. “You can take the boy out of the farm, but you can’t take the farm out of the boy.”

Steve and his father, Peter Markowski, run one of the East Coast’s preeminent Ferrari specialist shops out of three barns, behind a hill erupting with wildflowers in Vergennes, Vermont. Located an hour’s drive south of Burlington, among gently sloping farmland between Lake Champlain and the Green Mountains, Restoration and Performance Motorcars is as much a family enterprise as any of the surrounding farms.

The senior Markowski raised his family next door, and Steve and his brother Evan grew up in the shop, crawling around dashboards and riding bicycles in circles next to Ferrari Dinos. Like any good family business, they were put to work at a young age, sweeping up in the shop. Like any 12-year-old kids, they didn’t want to.

“My brother and I would sneak past so my dad didn’t see us; if he saw us, he’d put us to work,” says Steve, now 43. “So we’d sneak past, go in the house, and try to watch Seinfeld reruns—if he didn’t grab us by the collar first and say, ‘Get out there.’”

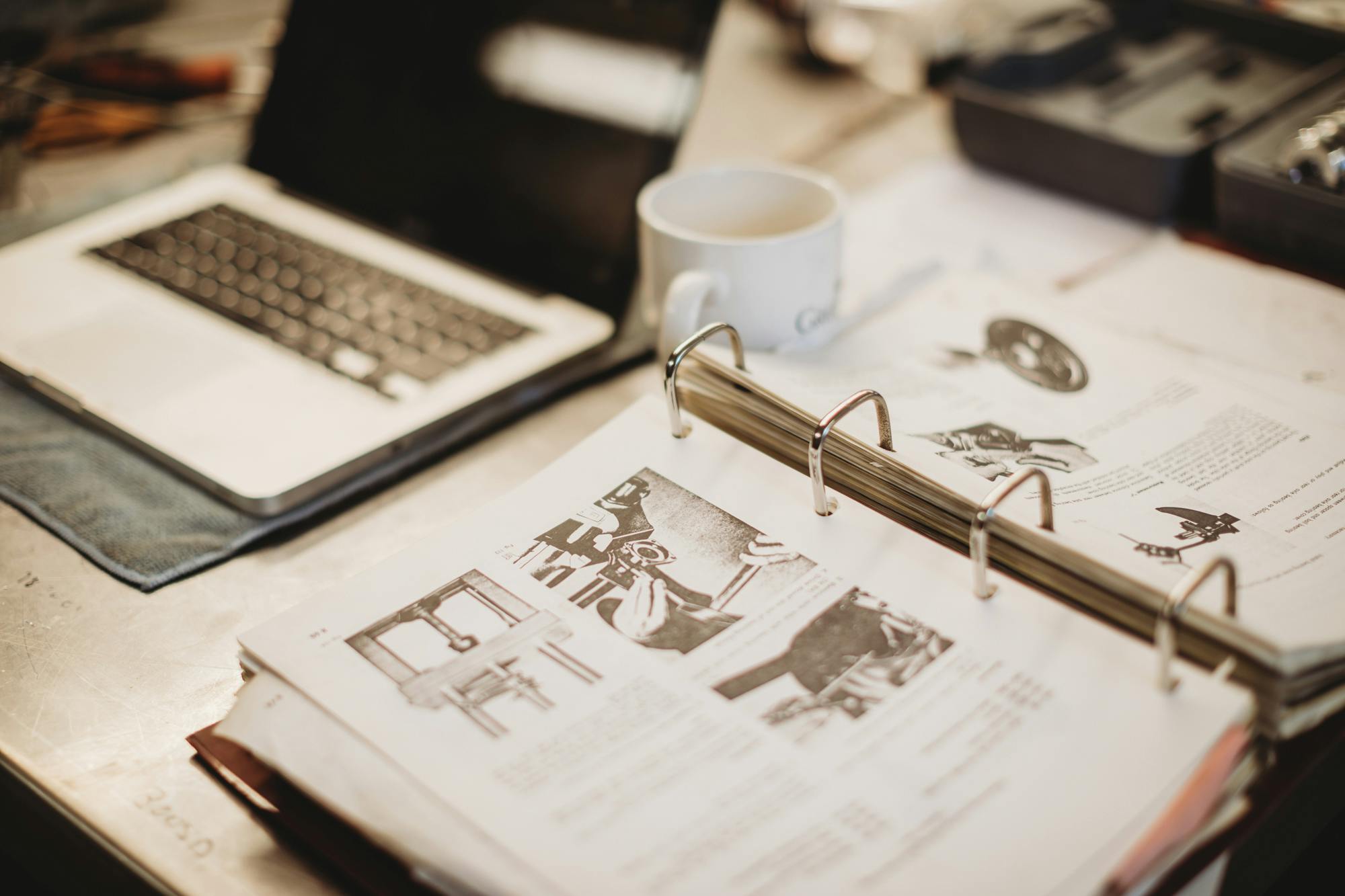

When we visited the shop, it was late summer in Vermont, a bright, muggy day. Summertime for RPM is the lull. Nineties rock blares from hidden boomboxes, and the air is warm with castor oil and grease, musty like a Victorian attic. Outside, a Jaguar E-Type announces its arrival from a shakedown drive with snarling fanfare. On the walls are posters of past Ferrari rallies, the design imitating 1920s art forms.

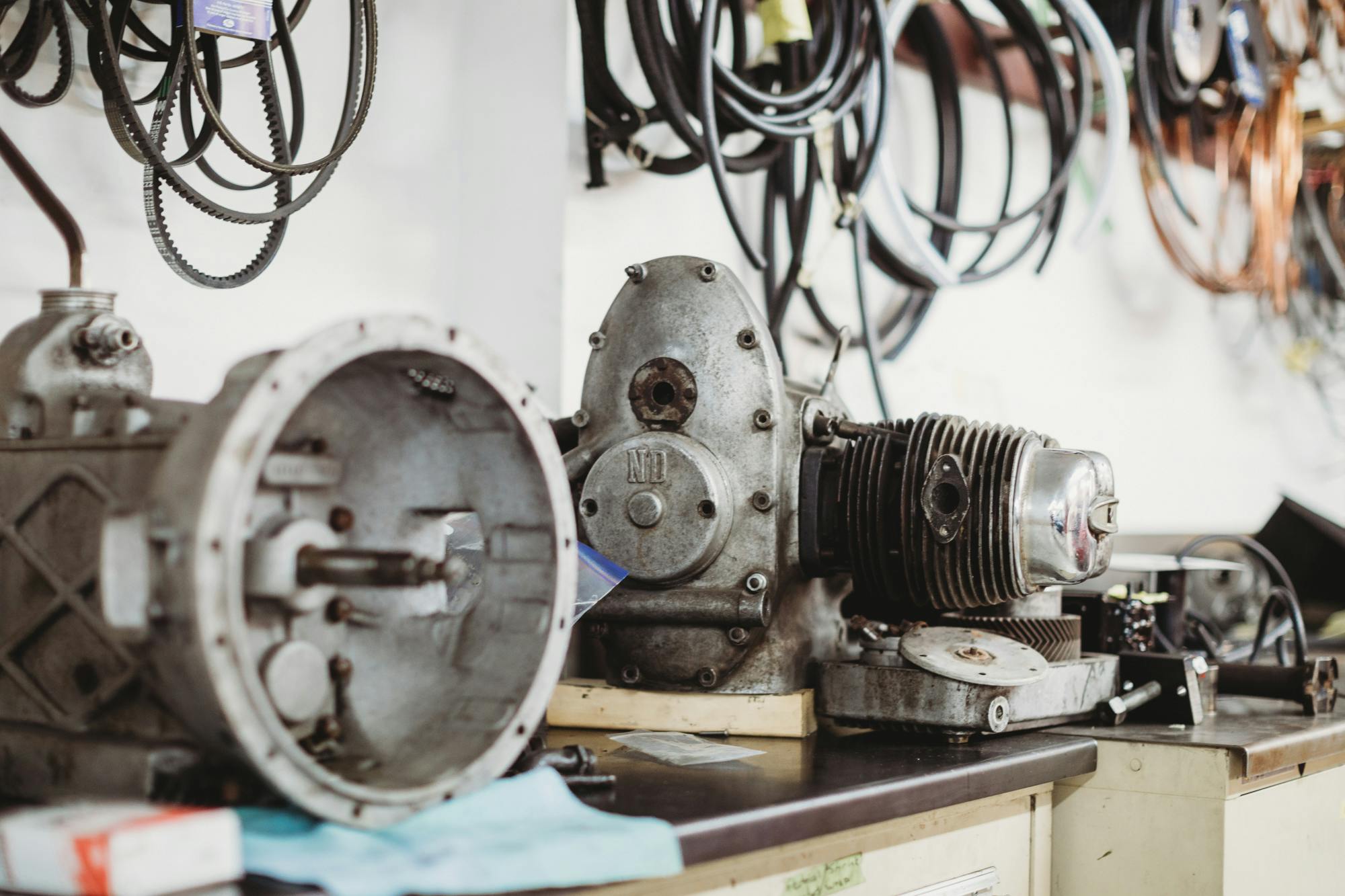

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

There’s also a poster of the official Ferrari magazine, Cavallino, featuring Peter Markowski’s own old warhorse (more on that later), and backrooms lead to other backrooms full of Italian artifacts. Here is the quad-cam V-8 of a Maserati Ghibli; around the corner is a Ferrari Daytona getting its Dunlop brakes rebuilt. In a separate barn, a Ferrari 308 GT4 waits for a new windshield, while a custom Mini pick-up truck demands completion. A Lamborghini Miura sleeps semi-naked, in need of new bodywork after its massive clamshell hood unlatched itself on a New Jersey freeway at 70 mph.

“We have been known for making cars actually work,” Peter says. “That’s not a normal thing. We have seen work done by shops from around the country, and even Europe, that we have to redo to actually make the car function.”

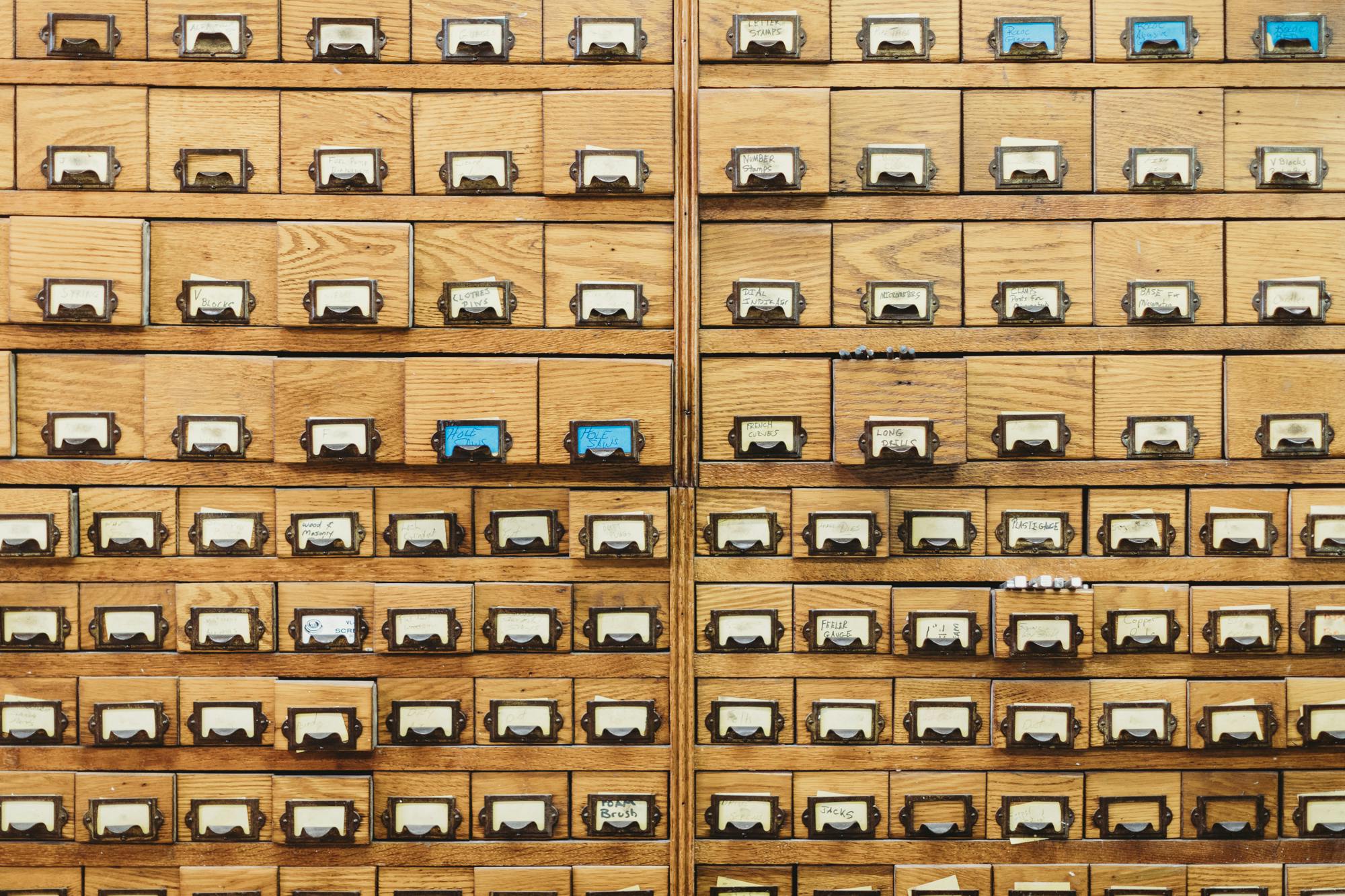

That includes replicating to rigorous precision brand-new parts to replace unobtainable bits that weren’t made very well to begin with. Steve Markowski says he’s lost sleep over the exact way to recreate the plastic levers that control the seat rake on a Ferrari Dino, which often break once they’re 50 years out of the mold.

“If only Ferrari, and especially Ferrari, had kept using metal switches and dials into the 1960s,” RPM wouldn’t have to manufacture replacements, he says. But because the carmaker no longer tools for them, nor sells them, he’s left with little other choice. And so Steve Markowski has become an obsessive artisan focused on re-creating original-equipment plastics, from door-release levers to radio knobs—all, he acknowledges, built with the same inherent weaknesses that originally doomed them to failure, because customers want exact replacements.

Steve muses that this “sickness” set in at an early age. He was about 18 when he noticed the rubber pads that inset on the bumpers of a Ferrari 250 were dry-rotted. “So I called around and I found some used ones. And guess what? They were used and old and cracked. I’m just, ‘Well, how hard is this?’” He made a mold, poured liquid rubber into it, and they came out perfect.

Steve’s father, Peter, grew up on a dairy farm in Rutland, Vermont, 45 minutes south of Vergennes. He learned to drive on a Ford dump truck. In 1958, when he was 12, an army sergeant neighbor returned from Naples, Italy, with a 1950 Ferrari 275S/340 America Barchetta by Scaglietti. He let Peter sit in it. Two years later, Sgt. Carroll Mills gave him a ride. Eventually, Peter gave Mills $500, a modest sum for a Ferrari nobody was able to relate to, and brought it home. Mills had not treated the Ferrari well, running it with hardly any oil. It took Peter seven years, but he got the Barchetta in working order. He owned it for the next 40.

“It was good to me,” Peter says, “and I learned a lot, met a lot of great people, and I became somewhat notorious for that. I had a chance to drive it across the auction stage at Pebble Beach four years ago. Did I cry? Sure. It was a big part of me.” Perhaps the sale price of almost $8 million helped sweeten the moment.

Peter has held dozens of jobs, from selling farm equipment to mortgage banking, from setting bowling pins in an alley (back when it was done by hand), to representing Freightliner Trucks. But that Ferrari 340 was always Peter’s impetus to work for himself. In 1985, he founded Restoration and Performance Motorcars from the basement of his home, initially tinkering on the Ferraris of friends, and soon building the main barn next door. Some of his earliest customers are still here. “I’ve had enough of this, working for someone else,” Peter recalls saying to himself. “Now I have to work for everybody. You go from one boss to many.”

Gone are the days where a cheap Ferrari 308 can roll into the shop with a belt and a fluid change and be on its merry way. Those cars are now four decades old, and your average Quattrovalvole requires a $25,000 engine-out service, Steve says. Some customers, understandably, balk at the costs. But what used to be castoff former play-things for the rich are now valuable investments, a changing shift in the very nature of enthusiasm. The standards must now approach perfection, even though no Ferrari was ever so perfect.

“In the old days, Ferraris were some of the poorest engineered cars on the planet,” Steve says. “They kind of got them together, and they kind of did the job.” You would know what he’s talking about if you’ve ever cut a hole in the floor of a $1.7 million 250 Lusso just to change out the master cylinder. “That’s not engineering,” he scoffs.

But Steve Markowski is also at peace with the fact that “Ferrari didn’t do anything conventionally.” It’s been very good for business.

The article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe to our magazine and join the club.