Media | Articles

Remembering Bill Neale: Artist, prankster, gentleman

If you love race cars, then you probably loved the evocative artwork of Bill Neale—even if you didn’t know him by name.

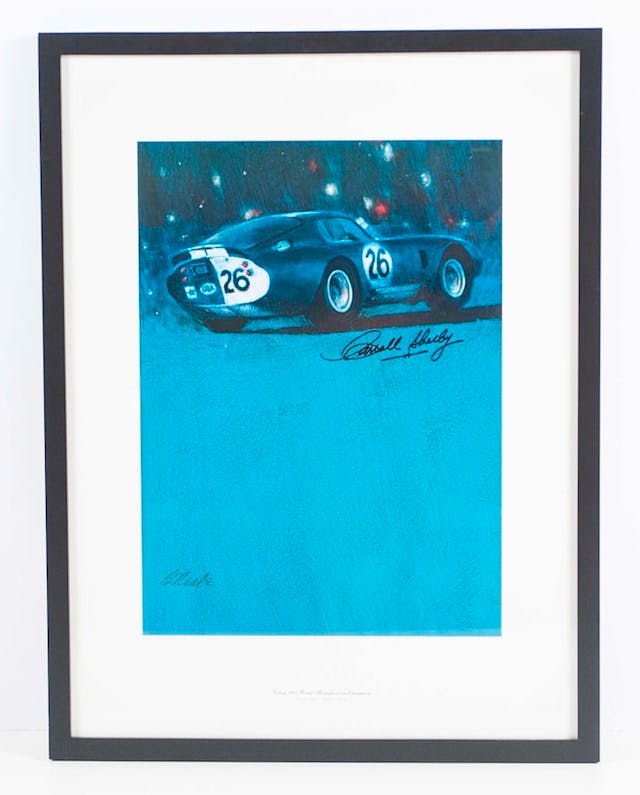

A prolific Dallas artist who died last week at 95, Neale painted the portraits that once identified the columnists in Car and Driver and Automobile, and his car images regularly appeared in Road & Track and Cavallino. His artwork formed the basis of posters for races and car shows, and his highly prized canvasses used dramatic details to capture the essence of racing without ever being slavishly realistic.

“He was one of the top four automotive artists in the country,” says BRE founder Peter Brock, who saw several of his cars—most notably the Cobra Daytona Coupe—memorialized by Neale. “His watercolors had such a fresh quality. But his paintings were never just pictures of cars. He was always telling a story because he was a historian of the sport.”

Gracious and charming, with a sly sense of humor, Neale was a longtime boon companion of Carroll Shelby. Both grew up in East Texas (and never lost their accents), both were pilots during World War II, both raced during the early years of the SCCA, and both loved to tell a good story. According to legend, Shelby—who was a serial divorcé—once asked Neale to fly out to California on short notice to serve as his best man.

“Shelby, I’ve got a card game,” Neale drawled. “I’ll be best man at your next wedding.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Neale studied art at the North Texas State College, then earned a master’s degree from the prestigious Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. After working his way up the ranks at the Tracy Locke advertising agency, he created his own firm, Point Communications, and was ultimately enshrined in the Southwest Advertising Hall of Fame.

Even while running his own company, Neale found time for painting. “He would stay up all hours of the nights working on something,” says fellow artist John Austin Hanna. In 1982, Neale was one of the six cofounders of the Automotive Fine Arts Society, which helped establish the art form as a legitimate (and commercially viable) discipline. For three decades, he regularly held court in the AFAS tent on the lawn at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance alongside his vivacious and indomitable wife, Nelda, whom he affectionately called “Scrap Iron.”

From the start, his art was informed by a passion for racing that took him all over the world. He was at Reims in 1958 when Shelby and Phil Hill entered their first World Championship Formula 1 race, and he was at Le Mans the following year when Shelby won the biggest race of his career. Neale was also friends with another racing Texan, Jim Hall. It was Neale who hand-painted the distinctive black “66” that’s forever been associated with the Chaparrals. “It just looked right inside the circle,” says Hall, who owns a Neale painting of a high-wing Chaparral 2E—bearing number 66.

This particular image displays several of Neale’s signature touches—an ominous sky framing the car, flying gravel giving the impression of speed and, above all, authenticity. “He understood how the wheels looked when they were spinning, how caster and camber worked, how the car loaded up in a corner,” says fellow AFAS member Charles J. Maher, who was one of many colleagues mentored by Neale. “His paintings looked like photographs—but better.”

Neale was one of the merry pranksters behind the creation of the Terlingua Racing Team, a fanciful operation, ostensibly located in a Southwest Texas ghost town near the Mexican border, devoted to fast cars and motorcycles, cold beer and hot chili. He also designed the team’s famous logo, which appeared on everything from Cobras and Trans-Am Shelby Mustangs to Indy cars. Asked why the jackrabbit on the shield was holding up its right foot, Neale said, “He’s saying, ‘No more peppers in my chili, please!’”

View this post on Instagram

Neale once gave Shelby an elaborate explanation for the other symbols on the coat of arms. The three feathers represented the three Indian tribes whose three languages, or tres lingues, gave the town its name, while “1860” referred to the year of the first race in the region, between mercury-ore wagons pulled by six-mule teams. “Neale,” Shelby said, “that’s a hell of a story. Where did you find it?”

“Shelby,” Neale said, “I didn’t read it in a book. I made it up!”

On a personal note, Shelby introduced me to Neale in 1984, saying he was somebody I ought to get to know. How right he was. Neale was a generous man and a gentleman—and funny as all get-out. Bill, we’re going to miss you.