Media | Articles

How F1 legend Phil Hill helped father the modern collector car industry

Just about everyone who has a passing interest in motorsports knows Phil Hill. He was the most successful member of the first wave of Americans to compete in European road racing after World War II. Besides being the first Yank to win an F1 race (at Monza in 1960) and the World Championship (in 1961), he won Le Mans three times (1958, 1961, 1962) as a Ferrari factory driver.

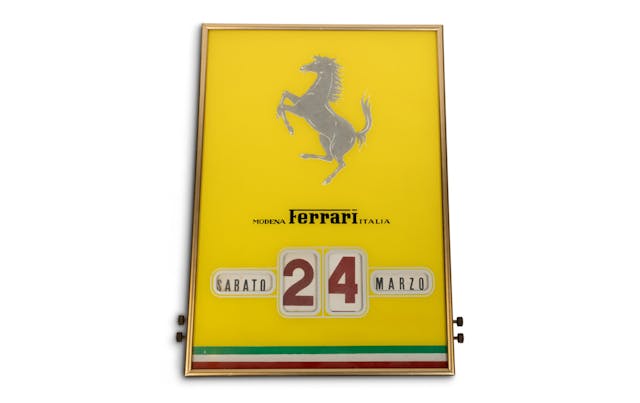

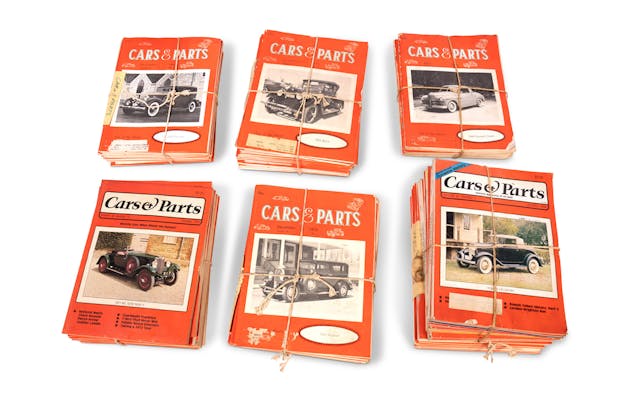

Fewer know that Hill’s influence on cars extends far beyond what he drove. Hill, who died in 2008 at the age of 81, amassed an automotive memorabilia collection so extensive and diverse—everything from a vintage powder-blue Dunlop race suit and a Sebring 12 Hour winner’s trophy to a Panhard & Levassor spare parts catalog and a Magneti Marelli ignition key—that it’s being sold by Gooding & Company in not one, not two, but three online auctions.

“He collected everything. He just couldn’t help himself,” says Phil’s son, Derek. “It’s absolutely gut-wrenching to put it up for sale. But at the same time, what good is all this stuff if it’s just stored in boxes?”

The auctions—the first of which closed last week, with others to follow in February and March—feature pieces of automotive history large and small as curated by America’s first Formula 1 World Champion. The collection itself also sheds light on the essential, though largely unsung, role Hill played in nurturing the modern collector car hobby.

Most race car drivers treat cars as little more than appliances. Hill, however, was infatuated by automobiles as mechanical and aesthetic objects. He was a founding member of the Classic Car Club of America, and his family’s 1931 Pierce-Arrow, which he restored, won the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance award for best of show in 1955 (the same weekend he won the Pebble Beach Road Race in a Ferrari 750 Monza).

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

After retiring from racing in 1967, Phil started working on some of his own cars in his home garage in Santa Monica. Along the way, he began “trading time” with fellow Packard owner Ken Vaughn. “Phil was a fearless mechanic. He would take anything apart,” recalls Vaughn’s son, Glenn. “And my father was really, really good with cosmetics.”

In the early 1970s, Hill and Vaughn bought two collections totaling about 50 cars and began restoring them. It was less a business than a way to stay engaged in semi-retirement while paying for their own projects. But word got around, and would-be customers started asking them for help with their cars.

“We kept telling them that we don’t do that,” recalls Bob Mosier, who began working for Hill as a teenager and later, with Hill’s blessing, went on to own one of the country’s premier restoration shops. “We just fixed up cars for resale.”

Of course, the restoration landscape looked a lot different back then. Remember, this was before televised auctions, before Cars and Coffee, before Sports Car Market and Hagerty Insider. The car collecting hobby was tiny, and so was the universe of collectible cars. A 10-year-old exotic was nothing more than a used car, and obsolete race cars were left outside to rot in the rain.

Top-shelf car collectors like Briggs Cunningham, J.B. Nethercutt, and Bill Harrah had staffs in-house. But full-on restoration shops were light on the ground, and most collectors served as general contractors, lugging their cars to individual craftsmen who specialized in engines, bodywork, paint, and so on.

After much badgering, Hill and Vaughn finally agreed to restore a Packard for a local ophthalmologist. Before long, they’d moved to larger facilities elsewhere in Santa Monica and began operating as Hill & Vaughn. Although it’s impossible to verify that this was the first large-scale high-end soup-to-nuts restoration shop in the country, there’s no question that Hill & Vaughn dramatically raised the bar.

In 1977, the company claimed its first best of show award at Pebble Beach, and Mosier remembers one year when it had no fewer than five entries judged as 100-point cars on the lawn. “If you wanted to be the cock of the walk at Pebble Beach, you came to see us,” he says.

By setting new standards for the business, Hill & Vaughn blazed a trail for dozens of no-expense-spared restoration firms for everything from Duesenbergs to muscle cars and hot rods.

But even as Hill was working with Vaughn on classic cars, he was also at the forefront of the burgeoning sport of vintage car racing. When Steve Earle was putting together what would be the first Monterey Historic Automobile Races at Laguna Seca Raceway in 1974, he asked Hill to come on board. “He said, ‘Sure, sounds like fun,’” Earle recalls. “He was a genuine car guy.”

At the time, hardly anybody cared about old race cars, either as investments or as playthings. By giving them a place to be seen and exercised, the Monterey Historics helped create a market for vintage race cars, which, in turn, enhanced their value and made restoring them a sensible (or at least defensible) business proposition.

Hill’s celebrity and willingness to participate in every aspect of the event attracted people to the Monterey Historics and conferred credibility on the vintage-race scene—and not just with collectors. “He was the catalyst who got other [pro] drivers to come,” Earle says.

But more than that, Hill led with “soft” power—the strength of his passion, the depth of his knowledge, and his unflagging accessibility and affability. “He was an ambassador for the sport,” says Phil Reilly, whose restoration shop—focused on race cars—sometimes competed against Hill & Vaughn. “At Monterey, if he was available and you asked him a question, he’d tell you a story or he’d tell you how to fix it or he’d help you fix it.”

Hill’s willingness to help fellow hobbyists was legendary. “My dad was so generous with his time,” Derek Hill says. “I have endless memories of him on the phone with anybody who called him up to ask a car question. He loved to help people solve car problems. He was like a hotline for car people.”

In addition to connecting with people on an individual level, Hill served as a sensei for millions of readers through the many “Salon” features he wrote for Road & Track, usually illustrated with luscious photographs by his close friend John Lamm, who died earlier this year.

Over a 30-year stretch, Hill covered not only the Ferraris he’d raced back in the day but also rivals such as a Lotus 18, oddities such as an 1886 Benz three-wheeler replica, icons such as a high-wing Chaparral 2F—even a 2001 Winston Cup Monte Carlo. Although Hill’s stories included his uniquely informed driving impressions, they were far more than mere road tests.

In these pieces, he did a masterful job of evoking a bygone time and place as well as profiling the people who created these seminal machines. But even though he wrote as the expert he was, he still geeked out over mechanical wonders and took childlike delight in the opportunity to drive the magnificent machines that he, too, had always fantasized about.

That was what made him such a great advocate for the hobby: Despite the fact that he was a giant of motorsports, he was, in the end, one of us—a besotted hobbyist who loved looking at cars, talking about cars, working on cars, and, most of all, driving cars.

“Phil was totally obsessed with cars long before he started racing them,” says longtime friend David Gooding. “I don’t think there was anybody who was more knowledgeable or passionate than he was. He was a huge influence because he touched so many people—not just in the racing world but in the collector car world as well.”