Media | Articles

Gerald C. Meyers, former AMC CEO, dies at age 94

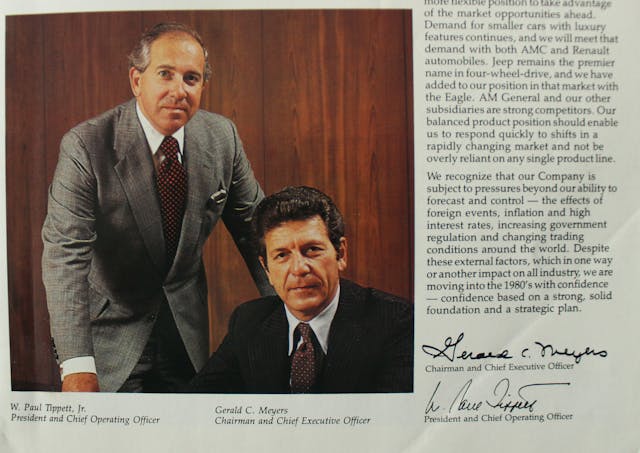

Gerald C. Meyers, former president and CEO of American Motors Corporation, died on June 19 at his home in West Bloomfield, Michigan. He was 94 years old.

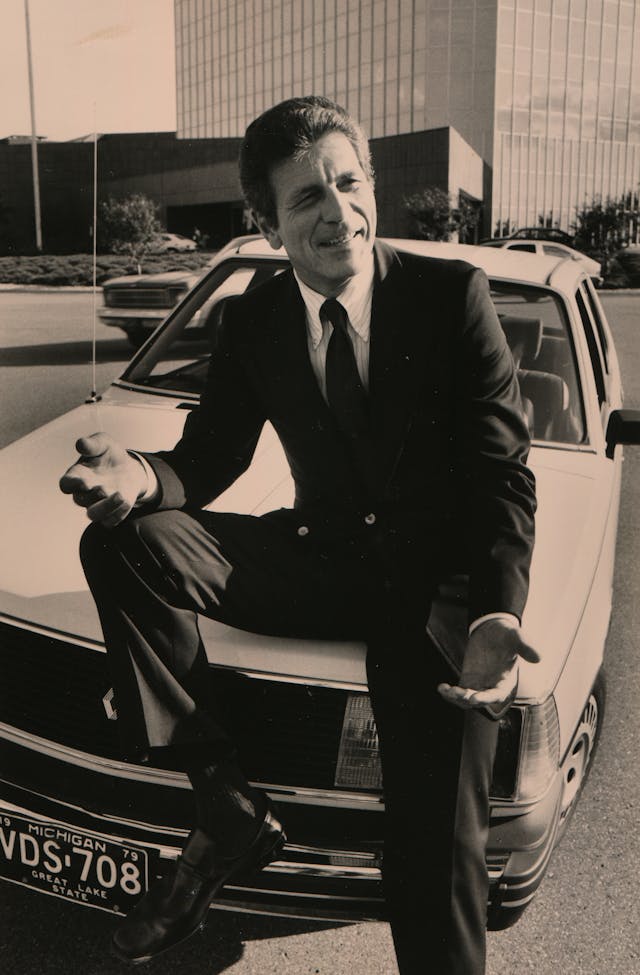

In the winter of 2017, I remember driving to a 1980s industrial park outside Detroit to interview Meyers for The Last Independent Automaker, our documentary on the automaker. My co-producer had convinced the notoriously cagy Meyers to do it, and I remember feeling nervous as we hauled our equipment into the small office.

At 88 years old, Meyers was still imposing. He was tall, square jawed, and deadly serious, with a deep, baritone voice. His memories of dates and production numbers were fuzzy, but he lit up when discussing the people he’d worked with during his 20 years at American Motors—George Romney, Roy Abernethy, Roy Chapin, Dick Teague, Roy Lunn. Meyers seemed always to be on the front lines of whatever the company was doing.

He had a colorful résumé, including stints at Ford Motor Company, the U.S. Air Force, Chrysler Corporation, and AMC–where he oversaw numerous products and projects from 1962 to 1982.

Tired of bureaucracy at Chrysler, he came to American Motors with hopes of faster career advancement. Starting as director of purchasing, Meyers did the granular but important work of calculating which parts were cheaper to build in-house instead of buying from suppliers. From there, he advanced to director of manufacturing, where he ended up sitting next to head designer Dick Teague on the flight where the designer made the infamous barf bag sketch that would become the AMC Gremlin.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

In 1969, chairman and CEO Roy Chapin Jr. assigned Meyers to investigate Kaiser Jeep’s Toledo facilities to see if American Motors should buy it. While it turned out to be one of the greatest decisions in automotive history, Meyers told us that he was staunchly against the purchase, at first.

“I didn’t know anything about Jeep. I didn’t think much of it. The volume wasn’t so wonderful and the vehicles looked kind of old to me,” he said during our 2017 interview. “But I went down, and I spent a week in the Jeep Toledo plant, talking to everybody I could get to listen.

The first thing that struck me when I walked in was how many people there were. The assembly lines were just crowded with people. A three-man job had ten men on it. A two-man job had four men on it. It was very inefficient, and the flow of material through the plant was archaic. There were parts all over the place, and the pace of the people who were building the cars was very slow.

And I said, ‘Roy, here’s what I think. I think it’s a disaster. You don’t want anything to do with it. It’s inefficient. It’s archaic. It’s absurd. And my recommendation is to forget it.’

Then they had a board meeting. Roy came out and said, ‘Gerry, come into my office. Now, sit down. We’re going to buy Jeep.’

I said, ‘You gotta be crazy! I’ve been down there, I did what you told me, I looked around. It’s a disaster! The costs are too high, it’s totally inefficient. The product is neglected. And I don’t know anything about the distribution organization, but the dealers are probably no good, either!’

He said, ‘Well, we just had a board meeting and we decided to buy it, and I’ve got something else to tell you. We’re going to put you in charge of it, and you’re going to make it work.’”

Meyers dutifully accepted the challenge, and his turnaround of Jeep helped lower costs and streamline production, as well as replace outdated powertrains with AMC’s in-house units. At the same time, his work on passenger-car manufacturing helped improve quality to the point where journalists were applauding AMC for building better cars than the Big Three. Meyers was promoted to VP of product engineering in 1972, putting him within reach of the CEO suite.

His record wasn’t all wins, however, as he was part of the board that signed off on the AMC Pacer’s development in 1971. It was supposed to be a modern, Wankel-powered urban commuter of the future, but the radical gamble didn’t pay off when GM canceled the rotary engine AMC had planned to buy. As a result, the Pacer ended up as an overweight, underpowered, economy car that wasn’t very economical, and its failure helped doom American Motors financially. A bright spot during this time came when Meyers helped engineer Roy Lunn get money to clandestinely develop the 4WD system that led to the revolutionary AMC Eagle.

As Meyers’ ambitions grew, so did an internal feud with marketing VP, Bill McNealy. Both wanted the company’s top job, and the battle turned ugly. Wrote Meyers years later, “McNealy and I carefully refrained from open hostilities, but alone with our people each of us moved with a vengeance to look good at our adversary’s expense. We learned first hand how destructive it is to an organization to select multiple heirs apparent, [with] the winner to be decided later.”

In 1977, at age 49, Meyers became CEO and president of AMC, making him one of the youngest leaders of any automaker. He beat McNealy for the job after selling AMC’s board of directors on his vision of the future. Knowing the company lacked the capital to design the all-new generation of fuel-efficient front-wheel-drive passenger cars that it would need to stay competitive, he recommended increasing profitable Jeep production and partnering with a foreign automaker to build new cars in the U.S.

“American Motors had been known for high fuel economy,” Meyers told me. “But we were not the fuel economy winners at that time. And we thought that one quick way to get onto the new wave, because of the price of fuel, would be to get smaller vehicles, and get them quickly. And that’s the reason I went over to France and made an offer to Renault.”

But even with the best of intentions, the Franco-American partnership struggled. After proclaiming that no stock would change hands, the 1979 oil crisis hit and the economy tanked, almost killing AMC. Renault was forced to buy 46 percent of American Motors to keep it afloat, which led to increasing French influence. Meyers developed an acrimonious relationship with Renault executive Jose Dedeurwaerder, who would eventually replace him.

“When Renault not only bought our company but decided to run our company, that was too much for me,” Meyers said in 2017. He left the American Motors Corporation suddenly in 1982, without publicly discussing the internal disputes. Years later, he candidly admitted, “By that time, my ego had gotten overcharged, and I felt if I can’t run this company, I’d better ought to leave it. And I did.”

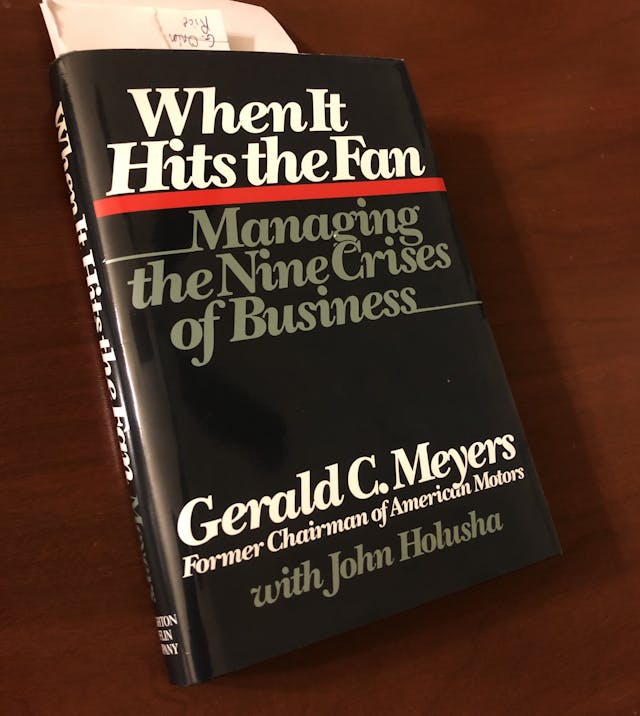

After American Motors, Meyers found his second passion as a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, his alma mater. He also ran a consulting business and published When it Hits the Fan: Managing the Nine Crises of Business, a book filled with corporate crisis stories, including many from AMC.

Even when I met him six years ago, Meyers was still working hard and keeping busy, although his pace was slowing. We had to cut our interview short, leaving me with the perpetual filmmaker’s remorse of wanting more. There were so many questions I still had to ask, so many more stories I still wanted to hear.

It’s easy to reduce a CEO’s tenure to a chart of yearly profits and losses, sales increases and decreases. But it’s a lot harder to pass judgment on someone’s choices when you’re actually sitting across from them, as opposed to reading about them in a car magazine. People are human. They have bad luck and do the best they can with what they’ve got to work with.

Meyers’ record is filled with ups (the Jeep turnaround, Hornet, Eagle, XJ Cherokee) and downs (Pacer, Alliance, the Renault partnership). He worked hard and made some incredibly difficult choices—ones that likely kept AMC in business far longer than it would have lasted under somebody else.

I returned to that office park several months later in 2017 to borrow some photographs from his secretary. As I examined the dusty pictures, I saw a side of Gerry Meyers that I had missed during my interview.

There was pride in his chiseled face—joy, even. I saw his passion for the work. The automotive industry meant something to him. He was serious, but sentimental, too.

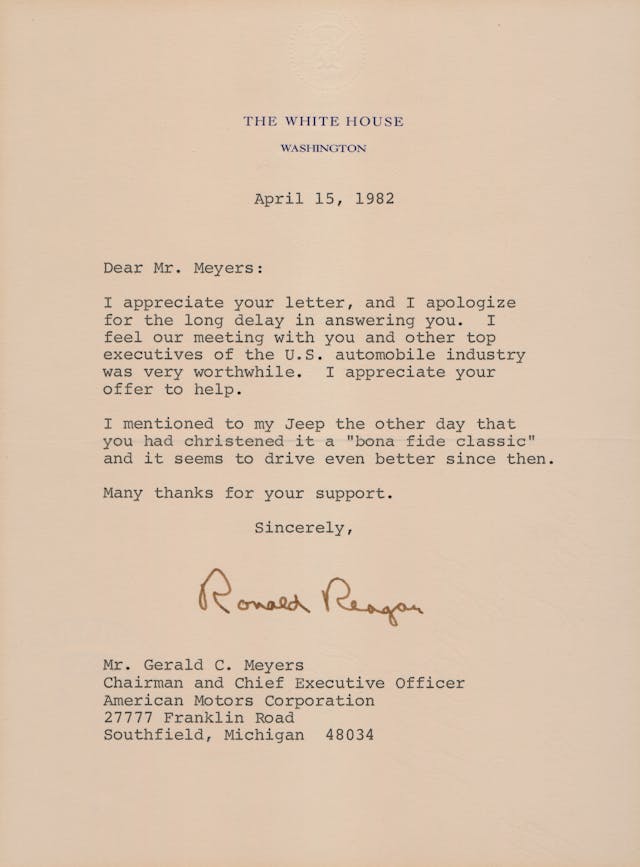

On the wall hung a letter from President Ronald Reagan, thanking Meyers for attending a meeting of auto executives at the White House. The president specifically enjoyed that Meyers had complimented the old Jeep CJ-6 he kept at his California ranch. Although Meyers hadn’t pointed it out during my first visit, I doubt anyone from GM, Ford, or Chrysler received such a letter.

Car enthusiasts may never recognize Gerald C. Meyers in the same breath as Lee Iacocca, John Z. DeLorean, or even George Romney, but his impact remains important. Throughout his career, Meyers brought action and energy to American Motors. Although I am sad that he’s passed away, I’m thankful we had the chance to capture his story.

Joe Ligo is the producer and director of The Last Independent Automaker. You can learn more and support the documentary here.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

There have been few who were as passionate about the auto industry as Mr. Meyers. He had his failings, to be sure, but as the author points out, he did more for AMC than anyone else likely could have. Hope he rests in peace.

He did appear to be an interesting man with an interesting company of cars.

The “merger” with Renault is often derided by AMC enthusiasts, but as an AMC historian I’ve seen a bit more of the financial crises that AMC was in. Without a merger with someone willing to put a lot of cash in AMC would have ceased to exist around 81-82. They probably could have carried on for a few years (maybe longer) if they had shut down the Kenosha assembly plant entirely and carried on with Jeep in the outlying plants (Brampton in Cananda and the Toledo plant, maybe the Milwaukee body plant). Kenosha was old an inefficient by the 80s. It was as efficient as it could be, but that’s not saying a whole lot. That’s the main reason Chrysler shut it down a year or two after taking over. A big problem was the UAW. Romney had negotiated a contract back in the early 60s when AMC was doing well to reward the workers, keeping a promise to them that if the company did good they would benefit from it. The problem was that this paid on average about $0.20 an hour more than the big three plants, and when AMC wasn’t doing so well they weren’t about to “give it back”. Chrysler tried to get the Kenosha UAW to accept the standard Chrysler contract, but they refused. Then they complained loudly that Chrysler broke their promise to keep the plant open. You can’t expect a company to keep a money losing operation going, especially if you’re not willing to help them make it a little more efficient. That was just one item, the old plant had other inefficiencies, but it was a big one. Chrysler didn’t really want Kenosha, AMC was just an all or nothing deal, they wanted the state of the art (when built) Bramalea plant and Jeep.