Media | Articles

Daring but doomed, Ken Carter was Canada’s Evel Knievel

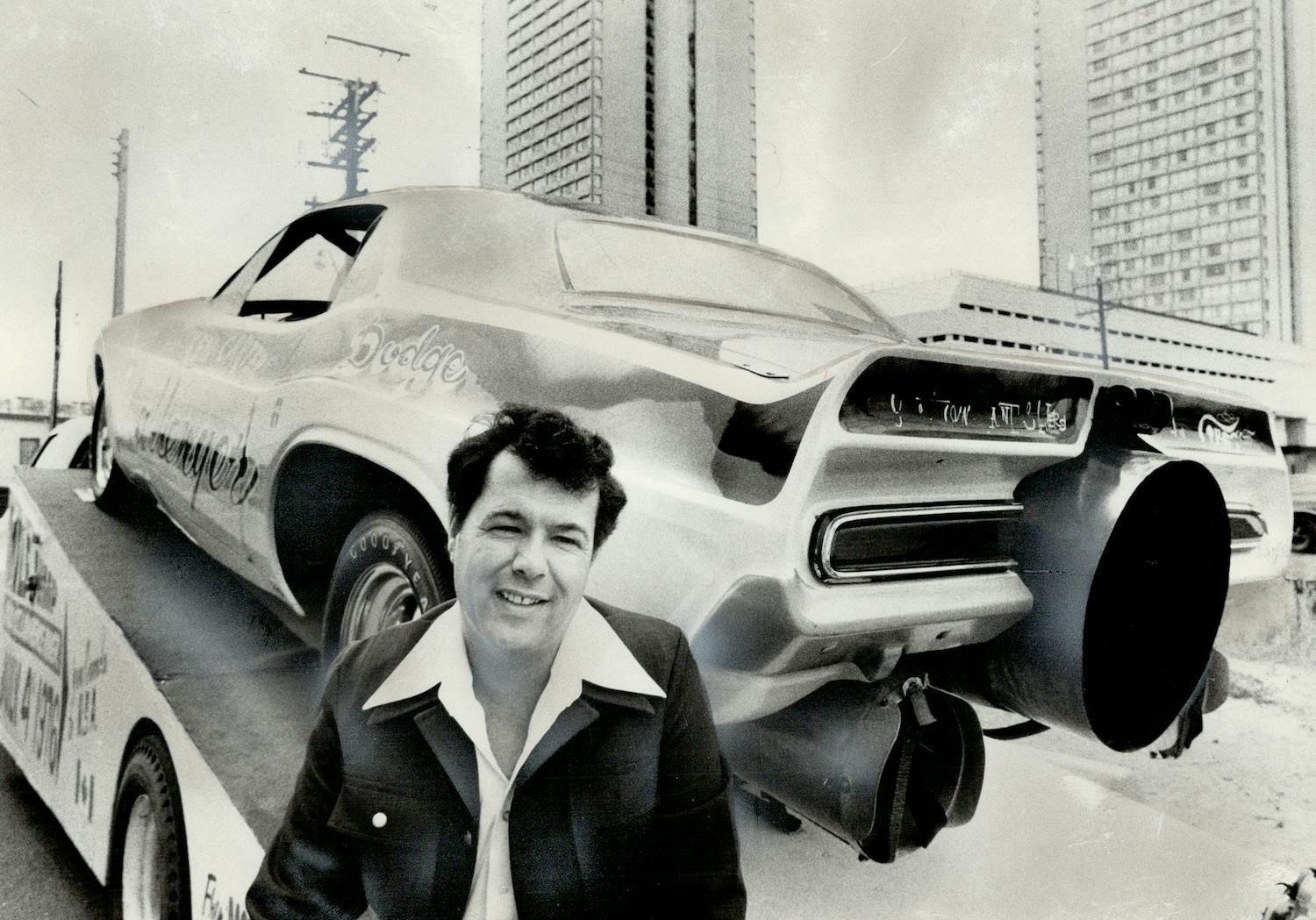

The man is clearly too big for the firesuit. On screen, he puffs and heaves. He can’t drive the rocket-powered car without this protective gear, but it matches neither his height nor his girth. When he finally gets the suit zipped, the stuntman can’t fit in the car’s seat. But that’s okay, because Ken Carter is a creative problem solver. He climbs into the cockpit of the rocket car in a t-shirt and jeans, lights off the engine, and shoots down the strip at 250 mph.

Before this moment, he’s never driven faster than 90.

Anyone old enough to remember the golden era of the daredevil usually thinks of people possessed of heroic skill and daring. Really though, these figures of legend were a bunch of regular guys with a high tolerance for getting hurt. Badly. In the course of his career, Evel Knievel broke an estimated 433 bones, a Guinness world record—and he was considered the most successful.

Then there was Ken Carter.

When invited to look over Carter’s most audacious plan, Knievel took one look and basically called it insane. “I don’t think I’d attempt to try this stunt,” Knievel tells the cameras, seated on the tread of a bulldozer. “This is maybe a daredevil stunt that might end all daredevil stunts.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

In 1974, Knievel had tried and failed to jump the Snake River Canyon near Twin Falls, Idaho. “Jump” is perhaps not quite the correct term, because the Skycycle X-2 used for the attempt was more missile than motorcycle, launched off a short incline as you would a rocket. The distance across the canyon was about a mile. Though Knievel would perform further jumps over his career, he would never again attempt a feat that daring.

Carter’s idea was even more bonkers. Instead of a missile on a track, he was going to use a rocket-powered Lincoln Continental and an enormous ramp to jump over the St. Lawrence River, which runs along the easter part of the U.S./Canada border. A huge earthen mound would be built, the car would filled with highly explosive hydrogen peroxide, and Carter shot into the air, hopefully to land on New York’s Ogden Island, over a mile away.

It never happened, and Ken Carter didn’t become the kind of household name that Evel Knievel did. But Carter came close, in a tragicomedy that blends pride, despair, unintentional buffoonery, and obsession. Like Knievel, Ken Carter had to jump. He was seemingly destined to do it—and he would die trying.

Kenneth Gordon Polsjek was born into poverty in a Montreal slum in 1938. He grew up hard, dropped out of school, and somehow found his way into the sideshow carnival of touring daredevilry.

Long before streaming services paralyzed overstimulated audiences with endless choices, people would go watch pretty much anything. If you lived in a small town and heard that a bunch of stunt drivers were going to show up and start crashing into each other, that was your Friday night.

Ken adopted the last name Carter and embarked on a career of showmanship that was anything but professional. The crew would roll into town, hitting up the junkyards for any old wrecked car that would still run. In the documentary Devil At Your Heels, Carter walks us through the process, giving a rusted out hardtop convertible a shake to show how rotten the frame is.

“It’s on this side, so it should be safe. But the car is not going to stay together. It’s definitely going to fall apart,” he says, walking the camera crew around the car. “We put some tape on it to hold the front of it together.”

Cut to the 1964 Chevy going airborne off a ramp truck and absolutely not clearing a line of old cars. Smash. “Arrgh!” screams Carter, followed by, “Easy on the foot!” His ankle is sprained or broken. “Go tell the people, tell them not to go away, tell them not to go away,” as his crew works to extricate him. “Take me over to that microphone.”

He’s lying on a stretcher, his hands shaking with adrenaline.

“Believe me,” Carter tells the crowd, “we’ll be back here tomorrow night.”

Everyone cheers.

It’s a hard way to make a living. Things get harder when television arrives on the stuntman scene, and simple crashes don’t draw the same crowds. At the time of the Chevy jump, Carter is 37 years old, and not healing as fast as he used to. But there’s still time.

Carter sees Evel Knievel as his biggest rival. In order to differentiate himself from Knievel, he jumps cars rather than motorbikes. But cars don’t fly—or land—the way bikes do. In order to best Knievel’s 1975 jump, when he cleared fourteen Greyhound buses successfully, Carter dreams of launching a jet car for a mile.

Over an active shipping lane.

With no real landing pad.

You did read the part about it being a mile, right?

Clearly this idea was madness, but it was madness at a time when people believed daredevils were capable of anything. At least, capable of trying anything. Carter’s laissez-faire approach to safety, as demonstrated by bare-armed rocket-car testing, was only appropriate for someone who’d attempt the most insane car stunt ever conceived. If he didn’t make it, he’d at least be going out in a blaze of glory. ABC’s Wide World of Sports gave Carter $250,000 to go ahead with the jump, aiming to broadcast it in September of 1976.

The rocket car was built by Dick Keller, the real-deal engineer behind the Blue Flame. That particular car went 633.407 mph at the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1970. For Carter, Keller built a chassis around two rocket engines that combined for a total of 11,000 pounds of thrust, only slightly less than Blue Flame’s 13,000–15,000 pounds. The fiberglass body of a Lincoln Continental was draped atop it, complete with stubby winglets to control the car in flight.

Rather than a bright and burning flame, the jump turned out to be a damp squib. After Knievel publicly pointed out how stupidly dangerous the stunt was, noting the hurried preparations and lack of safety, ABC pulled the plug. The ramp wasn’t ready in time, and there were problems with the car.

Carter kept touring and doing smaller jumps, but the years dragged on. Sponsorship for his big jump was hard to scrape together. There also seemed to be a growing reluctance on Carter’s part to actually make the jump. He delayed again and again. The closest he got was in the fall of 1979: He was within five seconds of making the jump, when the car suffered a mechanical failure.

At this point, the crowds had dispersed and the money was being fronted by a Hollywood film crew. Suspecting that Carter had lost his nerve, they substituted another driver last minute, a Carter-lookalike named Kenny Powers. Carter was unaware of the switch until after the horrific crash.

Powers had almost no experience with this kind of stunt and had never driven a rocket car. But even if he’d had superhuman powers, he probably couldn’t have held things together. The poorly constructed ramp was incredibly bumpy, and shook the car to pieces as it approached take-off. The parachute deployed and the shredded Continental tumbled into the water. Powers broke eight vertebrae, but survived.

It was the end of Ken Carter’s dream, but the coda is perhaps even sadder. He returned to the daredevil life, and the summer of 1983 found him trying to jump a 1982 Firebird over a pond in Peterborough, Ontario. He lost traction on the run up and put the car in the water. His next try came in September of that year. The Firebird was fitted with a homemade rocket, but somehow Carter got the math wrong. The car flew too high too fast, overshot the landing ramp, and crashed onto its roof. Ken Carter died instantly.

Today, the record for four-wheeled jumps is just 332 feet, well short of Carter’s ultimate ambition. The days of truly outlandish stunts are long gone, a fading memory preserved only by old Evel Knievel stunt cycle toys, packed up in a box in somebody’s attic.

Somewhere in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery in Montreal, the final remains of Ken Carter rest in an unmarked grave.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Cars simply don’t have the aerodynamics to do long-distance rocket-powered jumps successfully. Kneivel’s Sky Cycle X-2, on the other hand, was actually pretty well designed by Robert Truax, a Navy rocket engineer. The “bike” actually cleared the canyon, but an under-engineered parachute cover contributed to premature deployment which carried the vehicle back into the canyon. Close is only good in horseshoes and hand grenades, but Kneivel’s attempt was far more well thought out, and nearly successful, than the Carter/Powers attempt.

I saw Ken Carter do a jump at Cayuga Speedway. The Firebird had a built up 455 engine well muffled. He launched off of the bed of a tractor trailer and crashed into the landing trailer. It was supposed to be a copy of his Las Vegas trip. He tried the substitute driver many times. Smart promoters had in the contract that there would be no substitute drivers.

Ken Carter drove the car himself at Lancaster speedway

I remember that guy. As a kid I and everybody else was like, “Meh. Copycat.” Evel was it. Could you imagine the insanity Knievel would have attempted with the modern dirt/stunt bikes and practice facilities these Nitro Circus riders are using today? Those Triumphs and Harley Davidsons he jumped with were tanks.

Used to love those traveling Daredevil shows– Some friends & I use to try to emulate what they did–no helmets or other “Safety” equipment & often there was pain involved–but we did it anyway–Weather it was driving on two wheels/jumping cars or whatever–cars would end uo down side up & we’d flip them back onto their wheels, pull out the fenders from scraping the tires & get them running again & keep trying– Trial & error–We sure wrecked a lot of cars through those 5 or 6 yrs– I have fond memories of those yrs- But, it’s a wonder that I’m still walking-

Yes, why an unmarked grave? Yes, disrespectful. There must be some sad or troubling story behind that. Sounds like what someone would do who held a lot of hatred toward him. Please look into this back story! This would only be okay if the man himself requested it, which I doubt.

Hi. I would urge anyone interested in this story to listen to the Podcast called the Heavyweight by Jonathan Goldstein. Episode #13 is called Kenny and is a compelling telling of this saga. Totally engrossing.

It still blows my mind that this jump was attempted right near my home town. When you grow up in small towns, you don’t expect to be notable in any history.

The chassis of Carter’s Continantsl was built by Tom Daniels at SCAP in Alsip? IL. Keller built the rocket engines and helped engineer the car and “flight plan.” ABC hired me to shoot construction photos. I’m one of just a few who benefited from this debacle.