Media | Articles

Beneath cutting-edge tech, CXC Simulations runs on old-school car passion

Chris Considine builds triple-digit, state-of-the-art racing simulators for a living, but its a 1967 Mini Cooper S, passed down from his father, that triggers in him excited-kid-like hand motions and sound effects.

“It hops over things, gets airborne quite easy,” he says. “The kids are in the back going ‘woooo!'” The petite blue Mini in question sits in front of the understated brick headquarters of CXC Simulations, in Hawthorne, California, catty-corner to SpaceX Tooling. Clad in a trim, CXC-branded polo and dark jeans, its owner grins, flinging his hands in the air in enthusiastic reenactment.

When he founded CXC in 2008, Considine was one of the first into the business of racing simulators. The major challenge he faced wasn’t the technology, though; it was the expectations of his clientele. People thought of racing simulators as video games. Considine, who gave up formal education to work at the erstwhile Bondurant High Performance Driving School, knew there was more to the story. Unlike other stick-and-ball sports, there was no low-impact “practice” in racing. Golfers have driving ranges. Baseball players have batting cages. Racers had non-competitive track time, which required assisting manpower, consumed costly resources—gas, tires, brake pads—and carried only a marginally lower risk to life and property than the real thing. If designed and built properly, Considine knew that simulators could be cost-effective training tools.

Building a professional-grade racing simulator is, of course, hardly a plug-and-play affair. Though CXC sources its screens from LG, the 20-person team rewrites the firmware to minimize latency. “They have to be very quick-changing,” explains Considine, standing next to the headlining product in the CXC catalog. Triple 77-inch screens frame a bucket-seat equipped with a five-point racing harness, mounted on a base stuffed with a Dolby subwoofer. It faces a fully hydraulic pedal box and a racing dash mounted with a quick-release racing yoke. A five-foot stand close by holds four additional wheels, a short-throw shifter, and even an aircraft joystick.

“We look at feedback as a holistic thing,” says Considine, squatting to point out the motors mounted on the bottom and back of the seat. More units on the dash and steering column vibrate to transmit track texture and load the wheel in turns. There’s even a system of spring tensioners to help mimic on-track g-forces. Drop into the bucket seat and tighten the harness to competition-snug, and the simulator’s calibration ritual will yank them against your collarbones. The triple-screen array, complemented by a 5.1, 1500W sound system, presents a 180-degree field of view rendered in 1080p.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

With yours truly secured in the bucket seat, Chris keys in an iRacing test session: Road Atlanta, with a Radical in high-downforce configuration. Pulling out of pit row, he reminds me that the tires and brakes will be cold. Climbing up through turn one to two and down through the esses, my depth perception flinches as it decides to trust the screens. One, two, and who knows how many laps later, I realize I’ve lost track of time—but the chart of lap times reveals that the simulator is doing its job, even for your entirely amateur author. The times are dropping consistently. Extricating myself from the harness, my adrenaline-soaked brain struggles to shift back into reality and natural conversation: Sense of smell excepted, my body and mind are convinced I’ve been on track.

Any Motion Pro II can be built to order—single-screen configuration, for instance, if you own a Manhattan apartment—but CXC’s Special Projects division caters to a truly diverse set of clients: Those who want an exacting replication of a specific race rig, or deep-pocketed clients who simply crave “something different” in racing entertainment. Strolling past drill presses and TIG welders, Considine points out one such custom build: a compact simulator built to replicate a vintage Porsche rally car. The gated Quaife shifter and handbrake are the genuine articles. Want a Ferrari smoking kit in a triple-screen-rig painted Rosso Corsa to conjure your Ferrari? A one-to-one replica of an F1 car with VR goggles? CXC can make it reality—and has.

Of course, consequence-free racing is also great fun, and Considine and his team cater to those with serious money to spend on some seriously fun toys. If you want ten Motion Pro IIs in the upper loft of your car barn, CXC will build each one—and install an easy-to-use, touchscreen venue control system so you and your buddies can race each other in real time. “You don’t want to deal with a keyboard and mouse,” he says. “You want to do race after race after race, have a beer … you don’t want all the minutiae.”

Today, CXC Simulators boasts clients on every continent except Antarctica. Technically there are rigs in service even on the high seas; Norwegian Cruise Lines orders 7 or 8 Motion Pro IIs for each new boat (one each year), in addition to an all-out “halo” project. One of the first was a full-motion, two-seater Radical equipped with VR. The most recent takes things to another level … literally. When complete, this ex-Lucas Oil Pro Light chassis will float four feet off the ground. It’s mounted to a rig with dampers capable of three feet of stroke and fans that can mimic 80-mph runs through the desert. Walking around the tubeframe skeleton, which vaguely resembles an industrial dinosaur, Considine says that, in its current spec, the simulator can generate 2.5 g—which Norwegian politely requested that he modulate for the final product.

Ironically, given Considine’s success in motorsports-adjacent tech, his father Tim Considine didn’t encourage him to invest his time in racing. Beginning in his teenage years, Tim built a career as an actor: He co-starred as Spin in Disney’s serial Spin and Marty and played one of the Hardy boys in the eponymous Disney show. Later in life, Tim turned his attention to more literary pursuits, focusing particularly on sports (soccer, specifically) and motorsports. Though he owned a litany of bucket-list cars—a Jaguar D-Type and an alloy-bodied 300 SL, to name a couple—his son recalls that he quickly wanted to sample the next great thing. The humble Mini, mysteriously, stuck around.

To Mini aficionados, this original, U.S.-spec Cooper S has some delightful details. When Tim first bought it from the famous Hollywood Sport Cars dealership, he ticked the box for a Paddy Hopkirk pedal kit. The steering wheel and front seats got a similar treatment. “You almost sit on the frame rails,” says Chris.

Squint closely at the spokes of well-worn steering wheel, and you’ll spot the “H” and checkered-flag moniker associated with Mini’s famous Irish rally driver. You’ll also spot a set of tiny imperfections on the left spoke: “I think the marks on the steering wheel are from his [Tim’s] wedding ring.”

His father’s Mini may be a unicorn, but it doesn’t spend much time sitting still. Parked outside CXC Sims, the Graco car seat in its backseat testifies to its daily involvement in the Considine family life. Shuttling Chris’ 8- and 12-year-old kids to and from school is hardly novel for the Mini, either: “My dad use to take us carpooling in this car for years and years. When it rained he would do handbrake turns—perfect 180, 360-degree turns. This thing changes directions so quickly.”

The seatbelts across Mini’s back seat trigger another rather … dynamic childhood memory. “It never had seat belts in rear. One time, when I was their [his children’s] age, my dad had to slam on the brakes, and my head went straight into the dash. Dad went straight home and put belts in it.”

Keeping the car in fighting form is Chris Considine’s first priority. The car is technically on its second motor; following a front-end biff in the ’80s which damaged the oil cooler and eventually killed the bearings, his dad commissioned “his Mini guy” to build a second Cooper S-spec motor for the car. “Dad had the foresight to keep the original motor,” he says. “One day, I’ll rebuild that. Eventually, when this motor gets tired—I’m not in a hurry—I’ll swap it for [the] numbers-matching [engine].

“It’s a car! Drive it. If you hurt something, you fix it.”

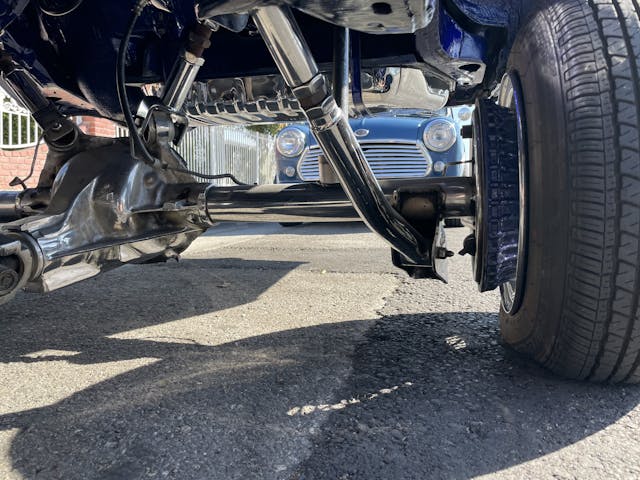

The changes Chris has made to the car are minimal, and focused on everyday usability. One of the Cooper S’s mechanical eccentricities was its “wet” suspension system, comprised of fluid-filled “displacer units” containing rubber springs and connecting the front and rear axles. First introduced on British Motor Corporation Limited (BMC) products on the Morris 1100, the hydrolastic setup was designed to mitigate pitching in short-wheelbase vehicles. Since lateral motion has a minimal effect on displaced fluid, body roll is well controlled despite a tendency to dive under braking.

Today, however, parts are scarce for hydrolastic suspension systems. They’re also are known to weep fluid, thus lowering the car little by little, and Chris grew tired of refilling the system each year to preserve the proper ride height. In went a more traditional, “hard” setup—control arms and shocks—though he took care to save the hydrolastic parts in a box should he or his children one day want to reverse the change.

Why would the young Considines be wrenching on the Cooper? They’re a bit shy of driver’s license age now, but Chris hopes to pass the Mini down to one of them as his father once did to him. Of course, some decisions must be made: There’s only one Mini to go around, so the other child will have to make do with the British Racing Green Lotus Emira that Chris has on order.

The daily operations of CXC Simulations may revolve around high-tech, high-dollar projects, but underneath the flashy screens and cutting-edge software, the Considine family business runs on old-school enthusiasm embodied by a humble, sprightly Mini.