Media | Articles

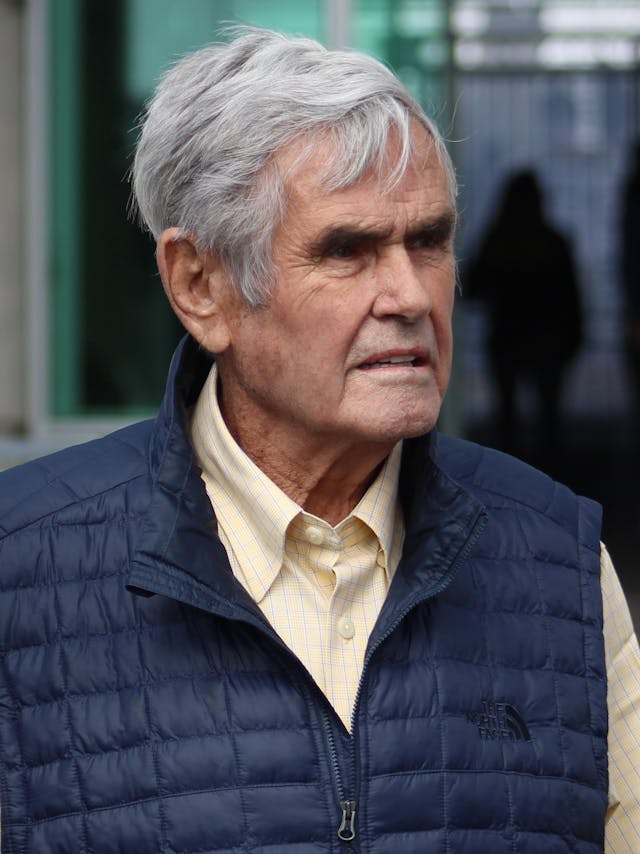

Al Unser was racing’s John Wayne

In the spring of 1987, guests at one of the finest hotels in Reading, Pennsylvania—the Sheraton at 1741 Papermill Road—were startled to see a truck pull up to the door and workers hastily load up the 1986 March IndyCar, part of a lobby exhibit to call attention to the then-Reading-based Penske Racing team.

The truck headed south to Interstate 76, which went west towards Indianapolis. What the workers may have said to the curious guests is unknown, but it was almost surely not: “This hotel-exhibit car is going to win the next Indianapolis 500.”

Which it of course did, with a recently-dismissed Al Unser making peace with team owner Roger Penske and agreeing to drive the car to his fourth victory there, in a car fitted with the antediluvian Cosworth DFX engine while Penske’s dream team, Danny Sullivan and Rick Mears, were running the newer Ilmor Chevrolets.

Penske’s third driver, 44-year-old Danny Ongais, hired to replace Unser with backing from Revenge of the Nerds film producer Ted Field and his Interscope racing company, had crashed a new Penske PC-16 into the wall at 11:44 a.m. on a Thursday during the sixth day of practice. It was the eighth of 25 crashes to occur during practice and qualifying. He was concussed to the point where doctors declined to clear the invariably sullen ex-motorcycle and drag racer to compete.

Unser, helmet in hand, had been prowling the garage looking for a ride, but he deemed all offers unsuitable and was on the verge of returning home to New Mexico until Penske held out a lifeline-shaped olive branch. The PC-16s had been a bust, and Penske was going back to the March chassis for all three racers, but the Unser effort—considered by some as a comfortable way to get sponsor Cummins onto a car—was lightly regarded.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Unser, who would turn 48 in a week, qualified 20th, nearly eight miles per hour slower than polesitter Mario Andretti. On the first turn of the first lap, Josele Garza spun and lightly tapped the car next to him, driven by Al Unser. While Unser’s car wasn’t damaged, Garza collected Pancho Carter, who had flipped during practice, with his helmet grinding against the pavement.

The race continued. Andretti was flying, taking only seven laps before he began passing back markers. Meanwhile, mechanical problems claimed the cars of contenders A.J. Foyt, Michael Andretti, Rick Mears, and the prior year’s winner, Bobby Rahal.

Then the race was tragically punctuated when Lyle Kurtenbach, a dedicated fan from Wisconsin, was killed when a tire came off Tony Bettenhausen’s car on lap 130 and was struck by the car of second-place Roberto Guerrero, launching the tire up to the top row of Grandstand K, where Kurtenbach and his family were sitting.

Unser drove his typically careful but quick race as faster competitors fell to the sideline. Mario Andretti was in complete control of the race, leading 170 laps and having put Al Unser almost two laps down. With 25 laps to go, only 12 of the 33 cars were running, some multiple laps in arrears.

Then, with a full lap lead, the famed Andretti Curse struck. An electrical problem led to an imbalance in the engine that caused a broken valve spring. He had led 170 laps, and even sitting in the pits, finished ninth.

Meanwhile Guerrero, after pitting to replace the nose cone broken in the collision with Bettenhausen’s tire, had made it back up to second place, taking the lead when Mario Andretti’s car failed. Guerrero had only to make his final fuel stop to win the race, and he entered the pits with nearly a full lap lead over a came-from-nowhere Unser. But Guerrero stalled the engine after the fuel stop and was passed by Unser.

Even with a caution flag on lap 192—for Mario Andretti, whose limping car had finally given up—Guerrero couldn’t catch Unser, who won by four-and-a-half seconds. Penske teammates Mears finished 23rd, Sullivan 13th, both retiring with engine problems.

It was an unusual victory lane celebration. Bobby Unser, Al’s older brother and a three-time Indy 500 winner, interviewed Al from the ABC booth, where Bobby was broadcasting his first 500 on television. “Everybody said, ‘I can’t believe he won the race,’” Unser said. “I said, ‘I can’t, either!’”

It was also the last time Al Unser was in an IndyCar victory lane. He raced in five more Indianapolis 500s—which included two third-place finishes—for a total of 28 Indy 500s. He led 644 laps there, the all-time record, and at 47, remains the oldest Indy 500 winner. Only he, Foyt, Mears, and Helio Castroneves share a record four Indianapolis 500 victories apiece. Unser retired in 1994, when his underfunded Arizona Motorsports Lola-Ford couldn’t get up to speed for the Indy 500 qualifications. Had he made the 500, he would have turned 55 the day of the race. His son, Al Unser, Jr., now 59, won that year, as well as in 1992, and the IndyCar championship in 1990 and 1994.

***

Al Unser, as you likely know, died last Thursday at age 82, seven months after his brother Bobby died at age 87. He had long been plagued by hemochromatosis, a condition that causes the body to retain too much iron, which likely caused a two-centimeter tumor to develop on his liver; the tumor and half his liver were removed in 2005.

Unser died at home, wife Susan by his side, in the idyllic village of Chama, New Mexico, elevation 7860 feet, located 120 miles north of Santa Fe in the southern end of the Rocky Mountains. While Unser’s fourth Indianapolis 500 victory may seem as though he backed into the win, there is nothing happenstance about his race record, which includes Indy 500 wins in 1970, ’71, and ’78; and overall International Race of Champions championship in ’78; a 1970 USAC championship; 1983 and ’85 IndyCar Championships and a total of 39 IndyCar victories in 332 races, run over a 30-year career.

Unser had his share of personal tragedies and trials. In 1982, his 21-year-old daughter Debbie was a passenger in a dune buggy that flipped in soft sand on the shore of Elephant Butte Lake in New Mexico. The buggy landed on top of her, and she died at the scene from a head injury. In 2009, his other daughter, Mary Linda Unser-Tanner died at 49. “Mary was always very loving and caring, she would give her right arm if she could,” her obituary read. “She never put herself first, she always thought about others, and she always had a smile and a laugh for everybody.” Son Al Jr.’s battle with alcoholism has been well-documented, with his fourth arrest for driving while intoxicated coming in May of 2019.

Through it all, to outsiders Al Unser was a taciturn, John Wayne-style racing cowboy, who liked to talk about most any subject but himself; when asked about his accomplishments, he mostly gave astronaut-style answers that didn’t delve deep, especially when brother Bobby was around—Bobby just answered any questions for him. A hail-fellow-well-met to friends, Al was a merry prankster, a departure from his tranquil public persona.

A consummate professional in any circumstance, Al Unser will be missed. Condolences can be sent to the Unser Family, P.O. Box 191, Chama, New Mexico 87520, or to the Unser Racing Museum, 1776 Montano Rd NW, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87107.