Media | Articles

A conversation with Peter Brock

One of the best parts of this job is getting to do some cool things like access to special cars or interviewing automotive notables. When I told a friend who isn’t a car guy that I’d interviewed Peter Brock, he didn’t know who that was. Since my friend is a music fan, I gave him an idea of just how “big” Peter Brock is in the automotive industry by telling him, “He’s sort of the Al Kooper of car racing and design.”

Kooper played organ on Bob Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone,” founded the band Blood, Sweat & Tears—writing much of their early music—produced some landmark recordings with his buddy, guitar god Michael Bloomfield, and discovered and produced Lynyrd Skynyrd. He has had multiple seminal roles in the history of rock and roll. Though as talented as Kooper is, even his best songs are not quite on the level of Brock’s Shelby Daytona Coupe, a singular masterpiece. Brock’s CV includes designing Bill Mitchell’s original StingRay racer, the basis for what became the second generation 1963 Corvette; penning the aforementioned Daytona Coupe; having a stint at Hino, where he designed a legendary Japanese supercar; turning Nissan’s Datsun brand into a formidable racing name with success in road racing (while giving the 510 sedan credibility as the “poor man’s BMW 2002”), off road, and NHRA drag racing; and now, when most people are retired, his next successful venture is making and selling lightweight, aerodynamic car trailers popular with racers: Aerovault.

Hagerty was given the opportunity to interview Brock when he was in the Detroit area to receive two well-deserved awards. He was the recipient of a Lifetime Design Achievement Award from the Eyes On Design show, where a number of his designs were on display on Father’s Day. He was also in town to promote the second annual American Speed Festival to be held in September at the M1 Concourse facility, where he will receive that event’s Master of Motorsports award.

Peter was affable, gracious, and is still very sharp at 85.

Our questions are in italics.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

You have a full and varied resume. You started out as a racer, you were GM’s youngest styling hire, designed some truly iconic vehicles, ran a successful racing team winning in a variety of racing formats—including road courses, Baja, and NHRA—had a run with ultralight and hang-gliding aircraft, and now trailers, plus you have BRE (Brock Racing Enterprises). What has given you the most satisfaction?

Boy, there are a number of different things. I think possibly it was testing at Le Mans in 1964. It was the first time we had the Daytona [Coupe] in Europe. You know, we’d run the Daytona at Sebring (winning the 12-hour race there), but nobody had seen it in Europe. Everybody was, “Oh, Ferrari,” which was all the big deal.

The most important thing was, Ford had just shown up with the new GT40, and the world was falling over themselves. This was going to be the hottest, fastest, most wonderful car in the world. They crashed both of them that weekend over aerodynamic instability, and we set the lap record on a wet track. So that sort of proved how good the (Daytona Coupe) car was. It wasn’t that we wanted to see Ford fail, they just didn’t have the development time in the car. I could have told them what the problems were in the beginning, but they were very secretive and jealous about their little program, and they didn’t want anything to do with the Daytona program.

What’s your greatest regret?

Oh, God, I don’t think I’ve got any major regrets. Minor regrets … every time a new car is designed and you get it finished, you say, ‘I could have done it better, if I had more time, or more money, or whatever’ and so on. Every car that I’ve worked on there’s stuff that I’d like to redo, but in general I’d say that I’m very pleased with all of it.

Which of your designs has come closest to what you were trying to achieve?

I think the car that I did for Hino in Japan. I did a car called the Samurai, a GT car designed to go endurance racing. A really pretty car, with a moveable wing on the back, it had all the good ideas on it. At the last minute they were absorbed by Toyota and they killed off the program. So it never got there. I’d say that maybe that was my greatest regret. It was a great looking car, but because of politics it disappeared.

You hired in at GM a very young age. What advice would you give to a young person wanting a career in automotive design?

That’s tough because the whole system of support for designers has changed. I think one of the advantages that I had going into it was I had spent a lot of time as a mechanic, and I had an understanding of how things actually worked mechanically. That gives you a basis of design; it’s almost like if you’re an artist you have to know the structure of the body. So having some practical experience, actually building cars, racing them. That’s why I think racing is so important, because you can get your hands dirty, so that really influenced the way I designed.

You mentioned artists needing to know the structure of the body. I was watching a livestream where comic book artist Ethan Van Sciver was drawing and he mentioned how there’s a a muscle in the forearm that is only prominent when the pinky finger is in a certain position, and in his statue of King David, Michaelangelo portrays that accurately.

Oh really! Isn’t that incredible? That he knew that it would show. Wow!

Both you and Larry Shinoda are credited with Bill Mitchell’s StingRay. Who did what?

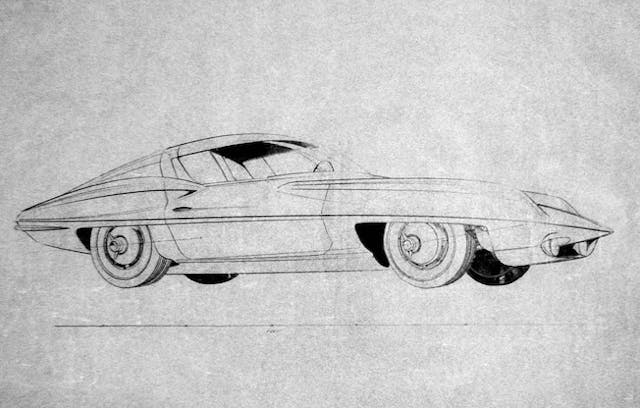

I designed the original car, Larry did the [1963] production version. The only thing Larry did on the 1959, which was the XP-87 concept car … Larry came in and did the headrest and its fairing that Bill Mitchell had him put on the car finally. But the car was designed under Mitchell. Mitchell designed the car; I was simply his hands. He directed it all, that was Mitchell’s car.

Mitchell could draw, couldn’t he?

He could, but he never did in the studio. You know it wasn’t until years after that I saw some stuff that he did at his outside design studio (after Mitchell’s retirement from GM), and he was actually pretty good, but he was smart enough to say that he was not going to compete with all those young guys that have all the latest techniques and everything.

Was Mitchell’s mouth really as profane as alleged?

Oh, absolutely! He was wonderfully profane.

You did the street version of the Daytone Coupe for Superformance, and they’ve also announced that they are doing a limited run of Ford’s 2005 GR-1 concept based on the DC. Are you involved in that?

No, the GR-1 is (former Ford exec) Chris Theodore’s car, and it’s a great looking car. Superformance has been talking about doing that car for five or six years.

Theodore just auctioned off the 2004 Ford Shelby Cobra concept based on ’03 Ford GT mechanicals, the concept that Carroll Shelby had a hand in—an updated version of the A.C. Ace-based original Cobra.

A lot of people have tried to do sort of a modern version of the Cobra. The thing is, you get too far away from it and it’s not the same car, and you get too close but it has badly-done proportions.

So you weren’t involved when Ford originally did the GR-1?

No, that all happened on their own. It is a very nice car.

What car designer do you admire the most?

[Without a pause] Oh, Gordon Murray!

Others that you admire?

Oh, a guy that worked with Zagato, I can’t remember his name. He did all the great looking Zagato cars. [I believe Brock was referring to Ercole Spada.]

Do you have a favorite car?

You have to go by era.

What’s your favorite era?

I have a weak spot for the ’30s. Those are really some of the great designs.

I’m a child of the ’60s, but when I saw my first Delahaye …

Fabulous, so far ahead of everybody.

Describe Carroll Shelby in one sentence.

Uh … [smiles to himself, pauses for a few seconds]. Probably the most charismatic crook I’ve ever met [chuckles a bit longer]. But if he was still alive and he called me to come back to work for him, I’d go back for him. We had a lot of fights. He did me bad on a lot of stuff, but I never would have gotten to do a lot that I did if it hadn’t been for Carroll.

What did you think of the Ford v Ferrari movie?

Terrible. No, let me correct that, great entertainment, but I know the real story, and if they had done the real story it would have been 10 times better.

You, Larry Shinoda, and Harry Bradley all were refugees from GM at a time when it was most creative, the early-to-mid 1960s.

Oh, absolutely.

Do you think you could have stayed at GM?

If I wanted to I could have stayed long enough. The only reason why I left is I had finished up the Sting Ray, and you know, I’m on cloud nine, working on a concept car for Mitchell, the whole thing, and I was like, what’s the next project? And they were like, ‘You know what? Maybe we’ll send you up to production to start working on designing taillights and stuff.’ And I was like, ‘Are you serious? I came here to design cars.’

You had to hook up with Japanese companies—first Hino, then Nissan—to go racing after leaving Shelby American. Why do so many important car guys have a love-hate relationship with Detroit?

I call it corporate inertia. You know, things get so complicated with the bureaucracy, the politics, the way things move when you’re working with that many people. Everything has to be organized with a plan to know what’s going on. You have these interminable meetings with all these people

That’s why I love what Gordon Murray does. Here’s a guy who knows exactly what he wants to be done, and he’s got the best team around him. He has to approve what every one of them does, and he knows that each of them can do their job better than anybody else, so anything he does is probably the best engineered car that there is.

How is Aerovault, your trailer company, doing?

My wife, Gayle, runs the trailer company, and it’s a great success. We’ve sold over 200 of the aerodynamic enclosed trailers to racers and collectors.

What’s next for Peter Brock?

I can’t really talk about it, but I can say that it’s a car to be made in Ireland by a company called AVA. [A little research shows that AVA is an EV startup by Irish entrepreneur Norman Crowley that will make modern electric vehicles with styling based on classic sporting automobiles. Brock will be joined by retired head of Jaguar styling, Ian Callum.]

Even at 85, Peter Brock can’t slow down.