Media | Articles

Vision Thing: The World Car fallacy

Since getting into this writing thing, one of the big joys of the gig (apart from conversing with commenters and seeing my untethered ramblings in digital ink) is digging deep into research. Rather, I get to read a lot.

As you probably gathered, I love reading. Being extremely on the spectrum (I have what used to be called Asperger’s), my preference is not for fiction. Anything remotely auto industry-adjacent, or automotive-related, however, is very much my thing. I’m physically incapable of walking past a thrift store or secondhand bookshop without investigating the treasures that lie within. There’s lots to criticize Amazon for (I try to use Abebooks these days) but the tech giant has finding obscure auto-related stuff much easier. When I meet my end it’ll probably be in a dusty house, stacked floor to ceiling with old car books and magazines. Something weighty, like Cars, toppling from a high shelf will connect with my head and deliver the final blow. I’ve made my peace with this.

I recently bought a copy of Brock Yates’ The Decline and Fall of the American Automobile Industry, and I’m about a third of the way through (time as ever being the enemy). The opening chapters describe in clear-eyed detail the complete failure to launch of the GM J-Car, and how those on the GM building’s 14th floor were as oblivious to the car’s shortcomings as they were obvious to those outside it. Which got me thinking about the concept of the so called “world car,” and why—on some level—it most often fails.

So, what is a World Car? In the past, when global markets were a bit more isolated from one another, it was long the dream of the major domestic OEMs to produce a mass-market car that could be sold on both sides of the Atlantic, and in Australia, with minimal differentiation. (It would sell in other developed markets too, but for brevity’s sake we’ll concentrate on the U.S. and Europe.) We’re not talking simply about a shared platform, but a rather complete car with negligible differences from Detroit to Dagenham, to Down Under. It could cost as much to develop car in Europe or Australia as it did in Detroit, so if these costs could be combined it would be an automotive buy one get two free. The savings would be astronomical!

Even though I’m in the U.K., you or I can equally walk into our respective local Honda dealerships this afternoon and (minor trim and equipment differences aside) buy examples of the same Civic. Rewind forty years and let’s say we’d tried the same experiment with the Ford Escort; one of us would have ended up with a reasonably competent mass-market hatch, while the other got an ersatz sort of copy that looked like it came from Wish.com. Remember both these (all three?) of these cars, because we’ll be coming back to them.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

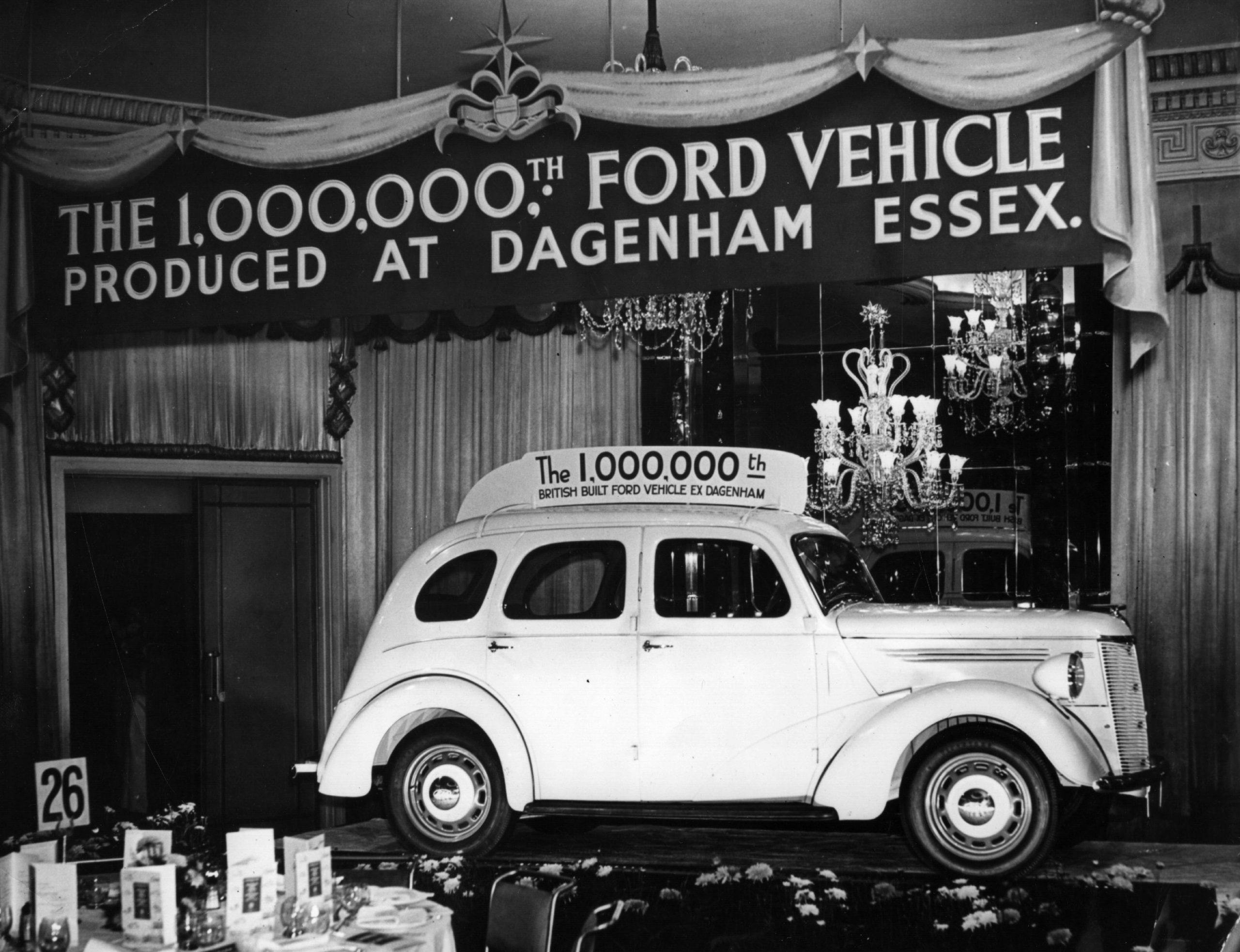

Ford inadvertently created a world car when it made the Model T, which sold all over the globe and whose manufacturing expanded to overseas with kits. Edsel Ford then took Henry’s River Rouge idea (raw materials in one end and cars out of the other) and transposed it to Dagenham just east of London in 1929. Dagenham is near where I grew up, and as a child I would always ask if we were going to go past the Ford factory, so I could see the huge Ford sign piercing the sky and the lines and lines of new cars parked up outside. (Car manufacturing has long since been offshored, but Dagenham remains as a major engine plant.)

Simultaneously, across the channel in Germany in 1929, Henry Ford started construction of another European plant in Cologne. It was a direct response to GM taking a majority shareholding in Opel, after GM had already purchased Vauxhall in the U.K. in 1925. Chrysler didn’t get into the Euro game until it bought the Rootes Group (mainly Hillman, Humber Singer, Sunbeam, and Talbot) in 1964. Chrysler’s Euro adventures were as messy as that lot sounds.

After the war, as ravaged Europe built its way out of devastation with help from the United States, car design and production began in earnest. Both Ford and GM now had separate design studios and engineering centers in both the U.K. and Germany, each developing their own models for their respective home markets—an incredible duplication of time and effort.

The U.K. has always had a slightly uncomfortable relationship with Europe, something post-colonial attitudes and two world wars helped amplify. In my humble experience, I’ve always thought the U.K. felt much closer to the U.S. socially, politically, and culturally than it does to its neighbors less than thirty miles away. Two countries separated by a common language, goes the joke. When Detroit decided it was going to start forcing closer cooperation between its Euro satellites in the early Sixties, there was a lot of resistance from the U.K. side.

What relevance does this fascinating history have to car design?

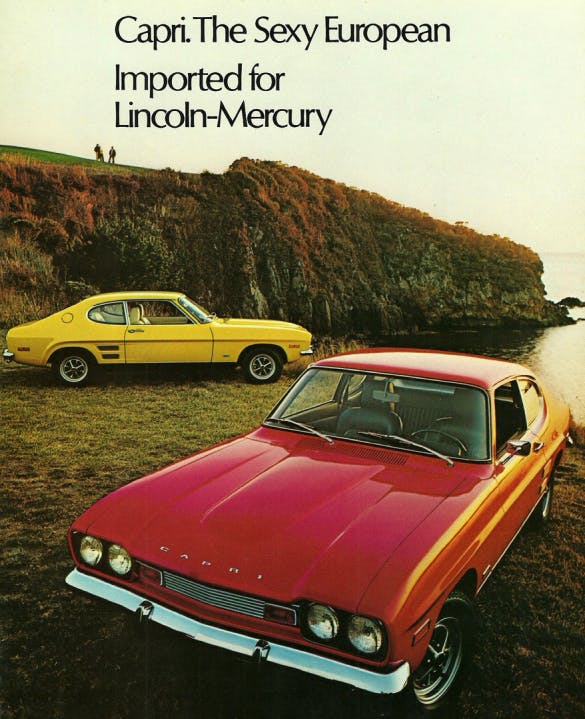

The first Ford of Europe (as it would come to be known) car was the 1968 Capri. Famously marketed as “the car you always promised yourself,” Europe’s “Mustang” was designed by the man who penned the original car, Philip T. Clark. Until exchange rates rendered it too expensive, the U.S. became the Capri’s biggest market, an indication that domestic customers were slowly beginning to turn towards smaller, nimble-driving cars with a hint of Euro sophistication and better economy.

This Americanization of European designs was no accident; designers and executives crossed the Atlantic regularly, an overseas posting on your resume was critical to ascending the ladder in Detroit. Look at the 1972 Vauxhall Ventora, or the 1970 Ford Cortina Mk3, and the influences are clear in the classic Coke-bottle hips and liberal use of chrome and vinyl. All of this brought a dash of Stateside glitz to the U.K., which was, even at that time, still a smoldering bomb crater.

The board was all set. By the early Seventies there was Ford of Europe, as well as GM’s Opel in Germany. Vauxhall had withered without investment from GM, and its offerings had become U.K.-built Opels affixed with a Griffin badge on the nose.

And then came 1972. That’s when the Honda Civic happened.

Although not conceived as a true world car, it was very much designed with export in mind, primarily to Europe. As the U.S. economy crashed and gas prices soared, the little Honda was suddenly the most fuel-efficient car you could buy. In the U.K., buyers were stunned by a well-engineered car that actually started on damp gray mornings and didn’t require a sleeves-up session every Sunday afternoon just to keep it running.

In a display of its burgeoning talent for advancements in the wrong direction, General Motors bolted first. In 1972 they came up with the T-car, a compact RWD platform that ended up underneath nearly all the GM brands worldwide. And because it was developed in both Detroit and Russelheim, the Vauxhall Chevette and Opel Kadett consequently sported completely different body panels to their American cousins, the Chevy Chevette and Pontiac T1000. Moderately successful despite their awful build quality and antiquated layout, the T-body cars were an expensive lesson in how not to design a car. GM refused to learn it.

Honda followed up the Civic’s success with the Accord in 1976. You don’t need me to re-litigate the impact of both these cars on the U.S. domestic market, as Detroit was shaken to its core. But we shall see that the real failure of GM’s subsequent compact, FWD J-car wasn’t totally due to the product. Blindness was the proverbial dagger—an arrogance as to how and why the market was changing.

One of the things that gets taught at design schools at the undergrad level is the creation of personas, a composite version of your target buyer. This considers age, income, education level and other socio-economic factors. You come up with a list of things these intended customers want in a car, and then use it to guide your design. Unimaginative students invariably come up with some idealized version of themselves, obscenely wealthy and successful at a young age, and then use that as an excuse to design supercars. It’s the sort of thing you do in university and then never do again, because once you get into an OEM there’s a whole marketing department with real customer feedback doing it for you.

Here we come to a fundamental design tenet. What exactly is your product going to be, and who is it designed for?

The Stateside success of the Volkswagen Beetle, another accidental world car, had convinced the GM brass that economical compacts were the purview of hippies, radicals, and other such anti-establishment types. This Bloomfield Hills and Grosse Pointe country club thinking blinded executives to one salient fact: Middle America was purchasing imports, as well.

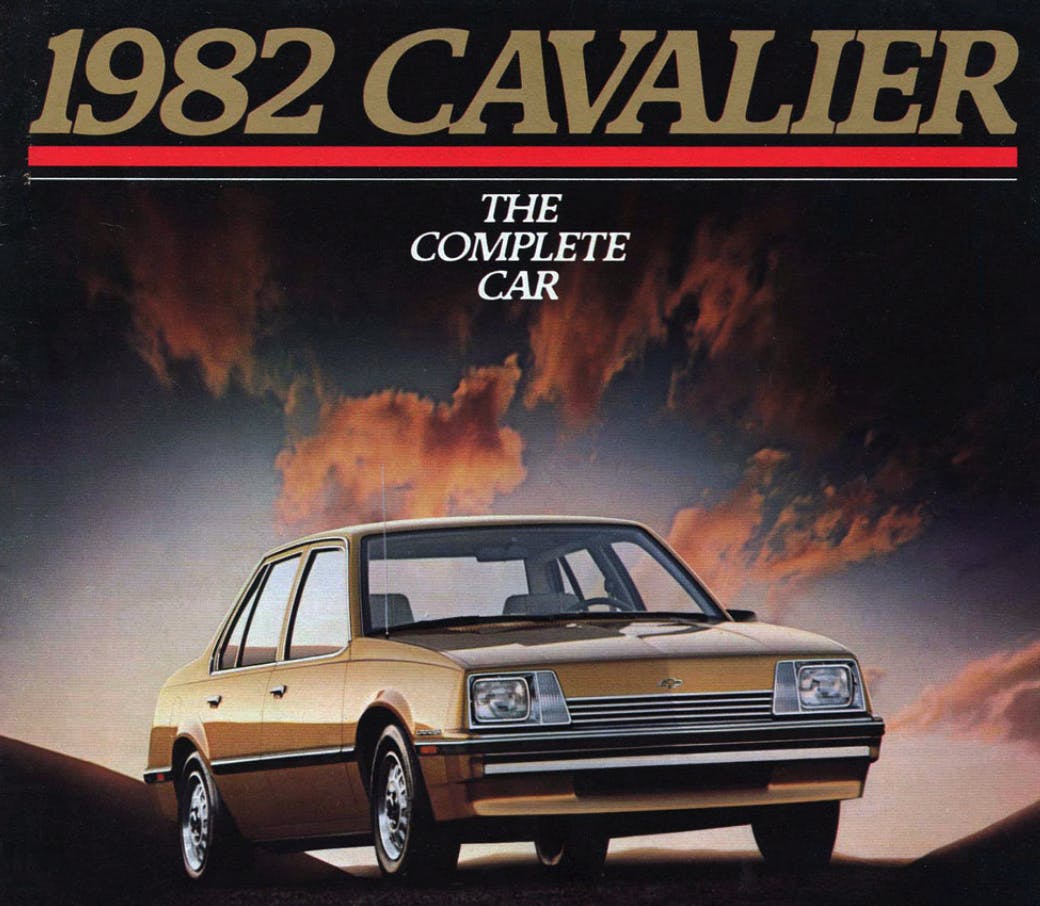

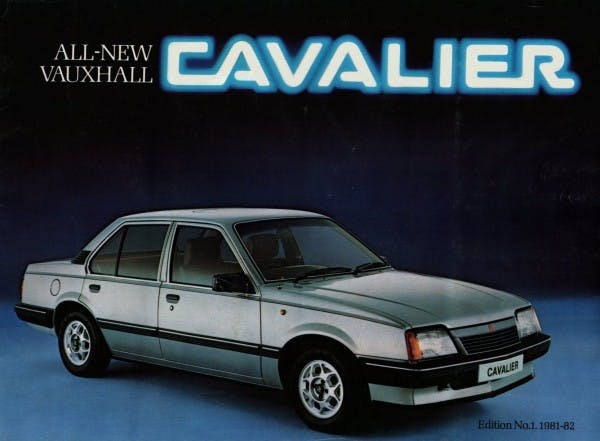

Here is what happened with the J-car. Tied to notions that served them well in the past, GM made the J-car a FWD parody of what had come before. Upon release in 1982, the J-cars were underpowered, overweight, and overpriced. Given the General’s numerous brands, it was also a badge-engineering job, which was something that did not fool American customers. The J’s only saving grace was that the European version had better engines and interiors. As a result, the Vauxhall Cavalier and Opel Ascona were well-developed and sold in good numbers.

Out of some sort of misplaced solidarity (or perhaps wanting a world car debacle of its own), Ford originally planned the 1981 Escort as direct replacement of the Euro Mk2 RWD Escort and the North American Pinto. Ford of Europe (FoE) was headed by Bob Lutz and he foresaw the new car must possess a FWD layout. Once the VW Golf and Civic appeared, Lee Iacocca (still a Ford VP at the time) had the sudden realization Ford U.S. had nothing to compete with, and demanded it become a global program. Hal Sperlich was the man in charge of the program in Detroit, but he was fired by Henry Ford II because of his closeness to Iacocca.

And then, seemingly overnight, one Escort design became two. Superficially similar on the outside, the two cars ended up sharing essentially nothing. They had the same wheelbase, but the U.S. model was longer and laden with additional trim: A stark contrast to the Euro model’s clean aero look.

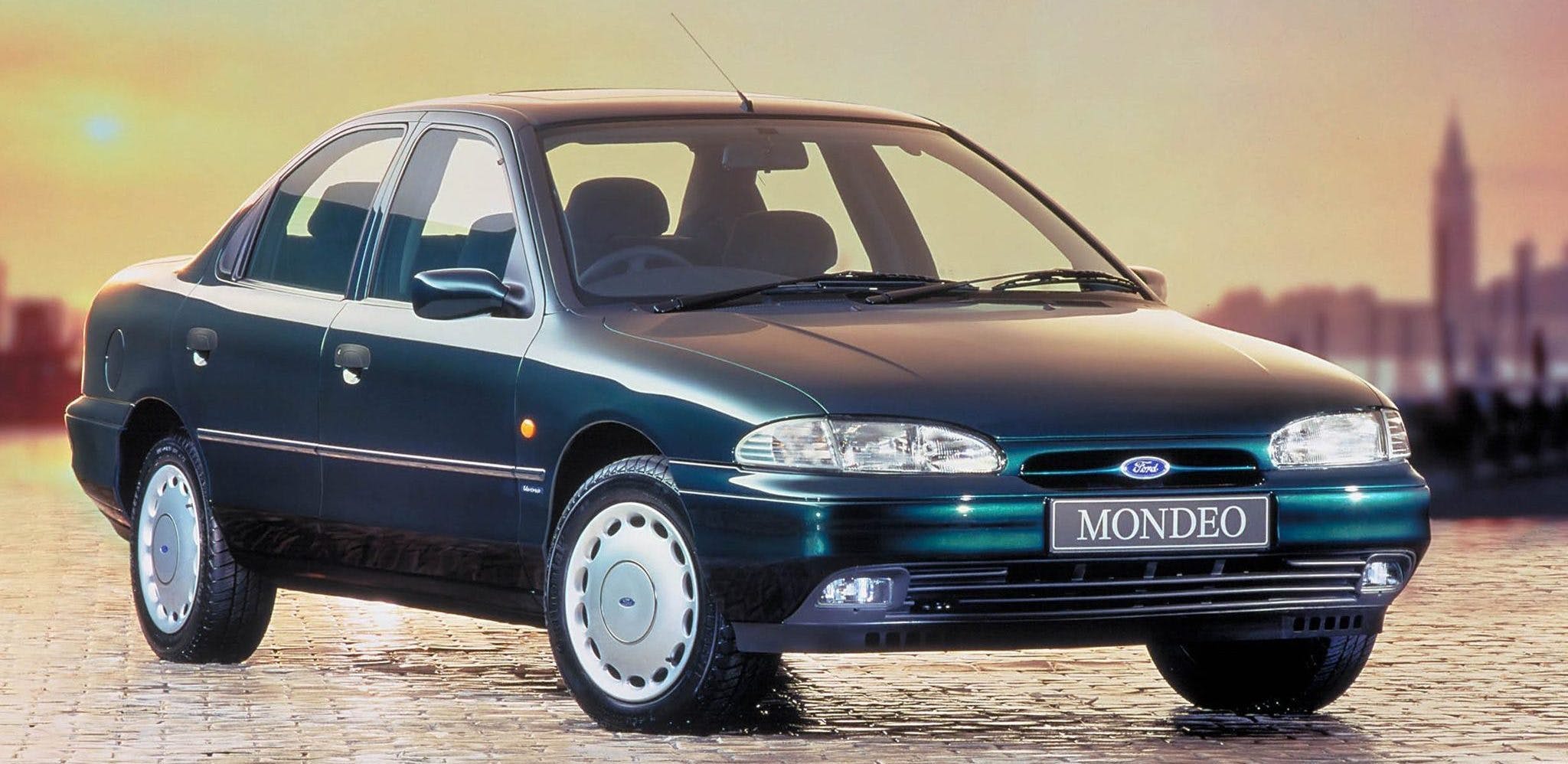

Ford tried again in the 1990s when it came time to replace the Sierra, a once-revolutionary looking car hobbled by decidedly less than state of the art RWD running gear. Allocating a staggering $6 billion for the development of the CDW27 platform, the idea was for FoE to lead the design, and utilizing Ford of America’s expertise in V-6 engines and auto transmissions. Because the U.S. versions (Contour/Mystique) were coming to market a year later than the Euro Mondeo (a made up name to signify “world”), Ford of America had time to improve the final design for domestic tastes. And they did, again ending up with two cars that were somewhat similar but had expensively different sheet metal. Fate always having the last laugh, the final 2014 Euro Mondeo was a rebadged Fusion, designed entirely in North America. Landing in Europe two years after appearing stateside, it was criticized for being too big.

Let’s not forget our friends at Chrysler. The Chrysler Horizon/Dodge Omni had a messy and half-baked development hampered by the fact Chrysler U.K. was in dire financial straits. But when Mopar was on its mid-Nineties design roll it came up with the Neon, Bob Lutz’s declared import fighter. It was good enough (alongside Jeep with the TJ Wrangler and XJ Cherokee) to spearhead another European invasion. Thanks to favorable exchange rates in Europe, the Neon was a cheeky-looking and conspicuous bargain that did reasonably well this side of the pond.

OEMs put a lot of effort into identifying markets and customers, then using clinics and surveys to preview designs. Thing is, you can manipulate these tools to get the results you want (which GM did with the J-car to tell itself what it wanted to hear). It takes a lot of money to do them properly by offering ride and drives of prototypes, which GM perhaps didn’t want to spend. Forget a persona, GM management hubris based on past success pointed to a type of customer who didn’t actually exist.

When Toyota wanted to get into the full-size truck market with the Tundra, its designers and project managers actually went out to parking lots across the America, on the weekends, to witness first hand how people used their trucks. This is the sort of knowledge you can’t get from check box forms. It’s enshrined in the Toyota Production System as genchi genbutsu—literally translated as “get your boots on.”

Remember what I said previously about how experiences are important for a designer? My first trip to the U.S. came about in 1999. I was chasing a woman (as always, doing things the hard way) and we met up in Atlanta. As we toured the American South on our way back to her home in North Carolina, I was amazed by the number of Japanese cars I saw in these American heartlands. Like the U.K.’s fractious friendship with the Euro mainland, I assumed there would be cultural resistance to vehicles from Asia.

You must challenge your perceptions if you want your designs to be a success. The Civic and Accord succeeded in spite of the fact that they were not American. They hit the mark because they were good cars that didn’t insult their intended market’s intelligence.