Media | Articles

Vision Thing: The art of war

It’s an old cliché that all great art must come from suffering. The myth of the tortured genius has probably been around since prehistoric man first daubed on cave walls, while onlookers pondered what exactly the artist was trying to say. Personal and professional trauma doesn’t merely produce great work; it adds a layer of meaning and complexity to our understanding of the art.

And it helps place the work in context. The band Fleetwood Mac wrote Rumours amid intrapersonal conflict between members who could barely stand to be in the same room as each other. Walt Disney, stung by a breakdown in his working relationship with Universal Pictures, created Mickey Mouse in secret out of spite.

For an example closer to my own heart, Nine Inch Nails gave us the seminal Downward Spiral, an abrasive, semi-autobiographical album about the downfall of a man, reflecting Trent Reznor’s struggles with depression and drug addiction.

(Your humble author has experienced more than his fair share of personal traumas, but I would never be so pretentious as to describe my work here or anywhere else as art. You, of course, are free to do otherwise.)

The debate about the inherent tension between art, design, and commerce is probably worth discussing in this column at some point in the future. Putting Warhol aside for now, a reasonable position to consider is the notion that, in the realm of consumer products, good design is properly considered as art.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Although design is an iterative, quantitative process with measurable objectives, there is an emotional component to boot. That artistic part is influenced as much by external circumstances and necessity as it is by the emotional state of the people creating it.

A designer, like the artist or any creative person, is a product of their lived experiences and their relationship with the world around them. Probably the most traumatic and world-altering event is conflict: John Milton wrote Paradise Lost after losing his wife, his daughter, and his eyesight. But he was mostly influenced by the English Civil War. War might never change, but it changes everything around it.

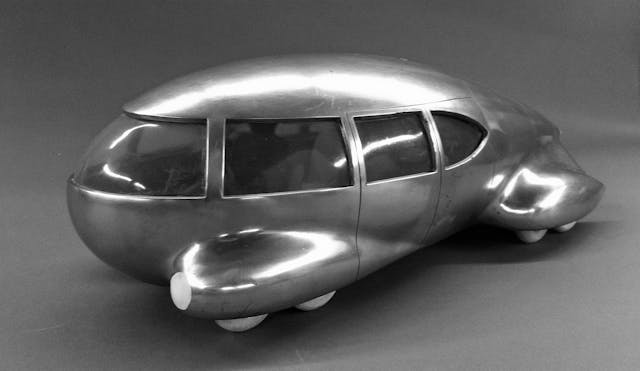

Prior to the Second World War, the aerodynamic “streamlining” of consumer products had been the purview of critical-thinking industrial designers like Norman Bel Geddes and Raymond Loewy, who each attempted to bring a more scientific approach to the design of the American automobile.

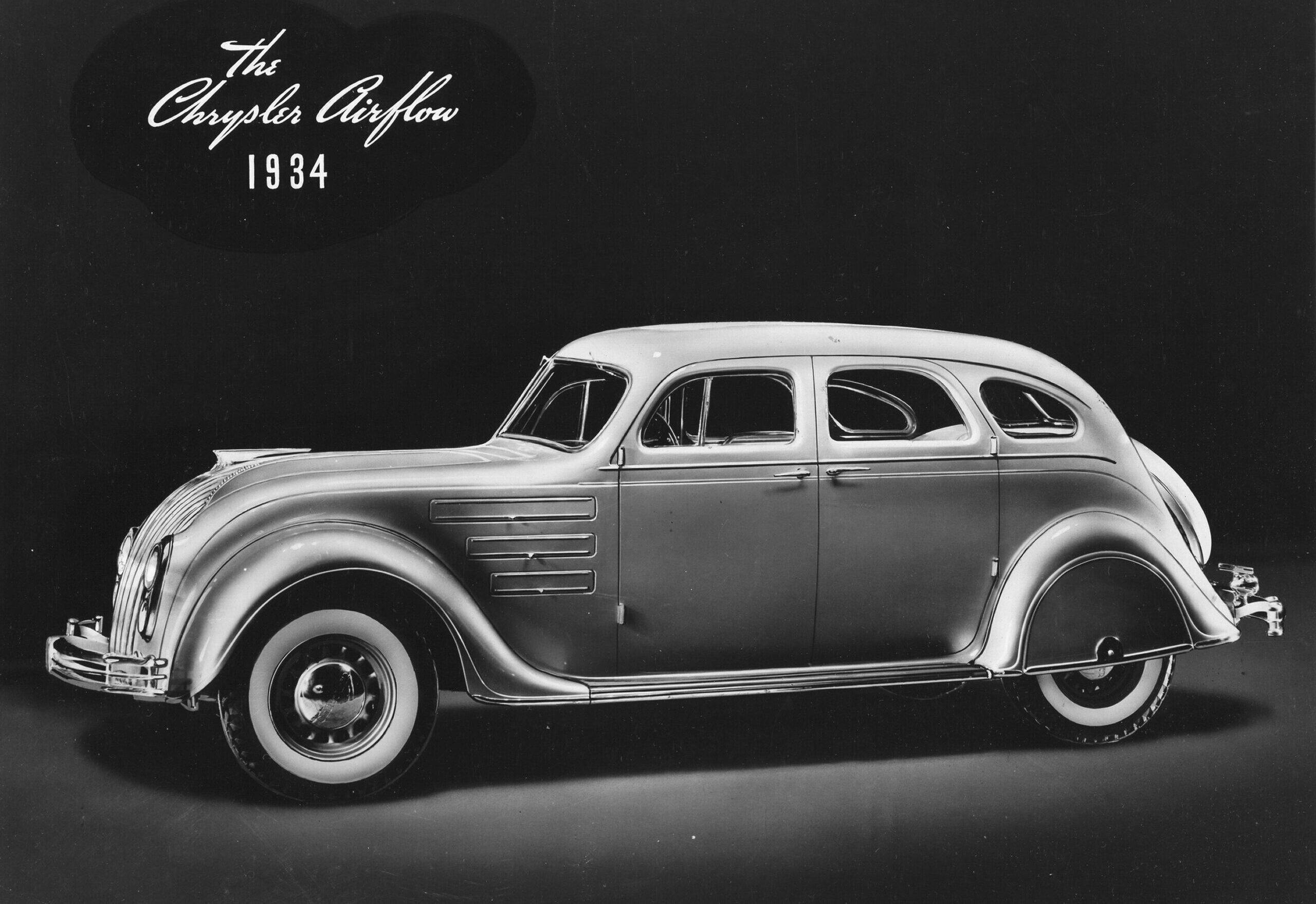

While Bel Geddes and Loewy had some success transposing the streamlined look to consumer products as a result of the art deco movement, streamlining as a directive was dismissed by Detroit after the failure of the Chrysler Airflow. The pure teardrop shape envisioned by Bel Geddes, Loewy, and the aerodynamicists wasn’t really suitable for a passenger car due to enclosed wheels and susceptibility to crosswinds.

It’s probably worth taking a brief pause to talk about the Airflow.

Although the aerodynamic science as understood at the time was reasonably sound, the execution was miles off. Ostensibly a unibody vehicle, in which the frame is integrated with the body, the Airflow utilized an elaborate but obsolete method of construction, one favored by low-volume, build-to-order luxury coachbuilders of the era: using small “filler” panels between larger body components, such as fenders, hood, and headlights. The Airflow may have had an advanced package with a roomy interior, but for a volume-focused company like Chrysler, it was incredibly time-consuming and expensive to build.

Compare the side profile of the 1934 Airflow to the superficially similar yet staggeringly more beautiful 1935 Lincoln Zephyr: Never was my point about car design being an act of nuance more starkly illustrated.

The Airflow was a disaster and only stayed in production for three years. Other advanced cars have failed in the marketplace by being too far ahead of public taste, but the Airflow’s problem wasn’t that it was too futuristic; it was simply too ugly. The breathtaking Zephyr, sketched by Tom Tjaarda and carried through to production by Eugene “Bob” Gregorie, was actually more aerodynamic than the Airflow and stayed in production until 1942.

Car design as a discipline was still in its infancy when the Second World War broke out. As factories transitioned to producing the arsenal of democracy, the government restricted car manufacturers from working on civilian vehicles. However, another unforeseen factor impacted the ability of American car designers to create new vehicles: They were cut off from their influences in Europe. Unable to work on new cars, the various design departments nonetheless began exploring ideas for the eventual resumption of car production when the war ended.

Edsel Ford, in contrast to his utilitarian father Henry, was an aesthete and connoisseur of the arts. He favored a more delicate and lighter appearance in cars, and encouraged Gregorie to explore ideas in this vein in preparation for the postwar Ford and Mercury lineup, hoping to introduce a more European-influenced look when the war was over.

Edsel’s intention was to have a tighter skinned car, with sculpted sides and pronounced but integrated fenders juxtaposed with finessed detailing. But Edsel passed away in 1943, and with him any chance of a postwar Ford that was visually lighter. Together with chief of sales Jack Davis, Gregorie had the idea of two full-bodied Fords, the larger of which would eventually become the ’49 Mercury.

At GM, Harley Earl naturally had his own way of doing things. He wasn’t one for artistic (or even scientific) theory and steered away from the controversy surrounding the Airflow. Becoming obsessed with the then-secret Lockheed P38, he began to encourage his designers to sketch full bodies with enclosed wheels—a typical Earl synthesis of ideas.

Bill Mitchell had left GM to join the Navy during the war and on his return he saw that these bulky but smooth GM cars had progressed a long way—but nobody working under Earl liked them. Mitchell described one Cadillac as looking like a turtle.

The upturned bathtub look that both Ford and GM were considering didn’t prevail. Earl had one of his characteristically explosive changes of heart. Ever with his finger on the pulse, he recognized the bulbous prop-driven P38 had rapidly become obsolete, replaced by something much sleeker and faster: the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, America’s first jet fighter.

Over at Ford, things were upended just as quickly when the firm caught sight of the first genuine postwar American car, the 1947 Studebaker.

Studebaker was in a unique position to capitalize on its competitors’ shakeups. Its design work was handled by an outside agency which was free to work on projects outside of the Department of Defense. That firm was Loewy Associates, and the ever contrarian Raymond Loewy had a lot to say about what he considered to be the failings of American car design. He envisioned a slimmer, lighter car free of what he called “spinach and schmaltz.”

Perhaps tiring of his outspokenness, in 1944 Studebaker executives deliberately supplied Loewy and his team with incorrect package dimensions, while instructing his second in command, Virgil Exner, to design the ’47 Studebaker in secret. Unsurprisingly, Exner’s was the design that made production, but Loewy’s ideas did directly and indirectly impact what Ford and GM were doing.

Ford purchased a Studebaker and pulled it apart. Working with the rest of Loewy’s team, Ford used it as a template for the smaller ’49 Ford. (The larger Ford had by this time morphed into the ’49 Mercury.) Earl also bought one of the Studebakers into the studio and incorporated some of its ideas into the ’49 Cadillac—the more integrated trunk and through fender line, while still retaining plenty of Earl’s trademark glitz and flair.

It seems appropriate that this tale of design subterfuge took place in wartime. Loewy was not a traditional “car guy”—something that would probably earn him scorn from the likes of Earl and Mitchell. (Although, as we have discussed before, Mitchell was extremely European in his outlook, just like Loewy). The irony is that Loewy, who went on to become one of the foremost American industrial designers, was heralded by the likes of the Museum of Modern Art for wanting to change the direction of American car design just as it was heading into one of its most expressive, expansive, and influential periods: the 1950s.

During my time in the studio, it was an unwritten rule we didn’t use any military vehicles as mood images or inspiration, and that we didn’t render up our ideas in a military setting. There were extremely sensitive reasons for this, but they don’t negate the fact that designers, like artists, always do their best work when circumstances are at their most challenging. Trent Reznor likely didn’t know what was coming his way when he rented 10050 Cielo Drive to record Downward Spiral, but the success of the final product clearly proves the point.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

1934 Hupmobile designed by Loewy stands up to the Zephyr better.

Even the Airflow is better in the 2 door coupe version. –4-door 30s sedans with the extra back window are the ancestor of the modern jellybean crossover after all.

The 1938 Graham-Paige “Sharknose” is a standout design to me. The Cord 810, Buick Y Job, and 1942 DeSoto are all part of the rise of design that would take cars fully away from the motor carriage heritage.

Good to see Studebaker getting the credit -they did some great stuff that holds up very well decades later considering the circumstances of an independent.

—-

I saw a Loewy-attributed graphic from 1934 called something like the evolution of design. Shows cars, trains, fashion, phones, etc. –if a legit piece, the call on fashion and phone is very accurate.

Everyone always forgets to mention the “Airstream” C6 or C8. While this was released to address some of the misguided “Airflow” stylings, it was FAR more attractive. If I saw the two side by side in a showroom, it’s hard to imagine why anyone would even consider the “Airflow”

There are a number of articles that allude to the role Studebaker designers played in the development of the 1949 Ford. It would interesting to know to what extent Ford’s product planners “reverse engineered” the Studebaker. A story about Exner’s travels would also be interesting.

Ford purchased a Studebaker, pulled all the exterior panels off, measured it all up and essentially reskinned it for the ’49 Ford. They even used Loewy’s team (without Loewy) to design it: Robert Burke, Holden Koto and Richard Caleal.

I’ll do a piece about Exner at some point.