Media | Articles

When it comes to belts and travel, it isn’t always as easy as packing a spare

I write a lot about the things most likely to strand you on a road trip—the so-called “Big Seven,” which includes ignition, fuel delivery, cooling system, charging system, belts, clutch hydraulics, and ball joints. Next to the others, belts might seem trivial—I mean, if you just carry a spare, you’re all set, right? You’d think, but it’s a bit more complicated than that.

First, let’s get the question of the timing belt out of the way, as it is by far the most important belt-related issue. Big American pushrod cam-in-block engines don’t have one, but if the car has an overhead camshaft(s), the cam is driven off the crankshaft by either a chain or a belt. If it’s a belt and the engine is a so-called “interference engine” where the valves come down into space in the cylinders also used by the pistons, you cannot afford to be wrong about the condition of the timing belt. If it breaks, the pistons will slam into the valves and ruin your engine, your day, and much of your bank account. Follow the manufacturer’s replacement schedule to the letter, and if you buy a car with a timing belt whose age and mileage are unknown, replace it and the tensioner assembly immediately (and, if you’re smart, while you’re in there, the water pump too).

In a vintage car without a timing belt, there’s often just a single belt. Usually referred to as “the fan belt,” it’s driven by the crankshaft pulley and typically runs both the alternator and the water pump (which usually has attached to it the mechanically-driven cooling fan needed to force air through the radiator to cool it at traffic speeds—hence the belt’s name). If it’s an old air-cooled VW or Porsche, there’s no water pump, and the belt instead directly drives the alternator, on the back of which is mounted the all-important engine fan. If the car has power steering or air conditioning or a smog pump, these are usually driven by their own belts. However, in the early 1980s, due to the increasing number of belts, the industry began moving away from individual belts to a common so-called “serpentine belt” that snakes around all or most of the accessories. In all cases, the belt that spins the water pump or fan is absolutely essential, as your car will overheat in minutes without it.

Let’s concentrate for a moment on the simplest case of a water-cooled vintage car with a single belt. Fan belts are usually V-belts that run in deeply grooved pulleys and are tightened by having the alternator swing in an arc. That is, there’s usually a thick boss on the alternator that bolts to a bracket on the front of the engine and forms the pivot point about which the alternator can move. A second bracket, either straight or arc-shaped, has an elongated slot in the end that’s bolted to an ear on the alternator. Loosen the nut and bolt on the bracket, use your hand or a pry bar to rotate the alternator, sliding the bolt in the elongated slot until the belt is snug, tighten the bolt, check that the belt deflects lightly with thumb pressure, done. What’s to go wrong? Well, more than you’d think.

Obviously, first, there’s the belt itself. Inspect it for cracking. Also check if it’s hard or shiny as opposed to feeling more like rubber. Sometimes if they’re old and hard, they can slip asymptomatically and cause hot-running or charging issues because they’re not turning the alternator or water pump consistently.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

One of the things that can go wrong is that the belt tension can loosen due to worn bushings that are there to insulate the alternator from heat and engine vibration. Depending on the make of the car and the alternator, there can be rubber or Delrin bushings in as many as three places—1) the wide boss on the alternator that’s the pivot point, 2) the small ear on the alternator where the adjustment bracket attaches, and 3) the other end of the adjustment bracket where it attaches to the engine. If there are bushings at the pivot point, and if they’re worn or soft, it causes the alternator to cock so its pulley is no longer parallel with the crankshaft pulley. This causes the belt to loosen. Tightening it will just cause the alternator to cock further, resulting in premature belt wear. This may sound like a minor annoyance, but I’ve had road trips jeopardized because the belt wouldn’t stay tight, causing the car to run hot and the battery not to charge.

Wear in the other bushings may not cause the alternator to cock but may still make it impossible to keep the belt tight. To replace either of the alternator bushings, the old gooey rubber must be cleaned out with rags and solvent, and the new bushings pressed in with a vise, large slip-joint pliers, or a threaded rod and washers.

The other style of belt is the serpentine belt, so named because of the snake-like way with which it circumnavigates the accessories at the front of the engine. A single serpentine belt will usually run the alternator, water pump, and power steering pump. If the car also has air conditioning, the compressor may run off the same belt or may have its own belt. Serpentine belts are wide but thin and flat, with multiple grooves in them that sit in the pulleys in which they ride.

Two things allow the serpentine belt to do its serpent-like twisting around the components. One is the thinness and flatness of the belt itself. But the other is the presence of several smooth (non-grooved) idler pulleys. In contrast with the grooved pulleys on the crankshaft and the accessories that receive the grooved side of the belt, the idler pulleys are in contact with the smooth back side of the belt.

One major distinction between a serpentine belt and the V-belt is that you generally don’t manually adjust the tension on a serpentine belt. Instead, there is almost always an automatic belt tensioner located on one of the idler pulleys. The tensioner may have a rotational spring in it, or it may use a little pressurized hydraulic cylinder.

Because of the presence of the tensioner, you rarely have the problems with belt loosening and slippage that you do in V-belt systems. Unless something in the tensioning system fails, the serpentine belt stays tight. And the mounting of belt-driven components is simpler, as you no longer need the alternator to rotate in an arc or the power steering pump to move downward in slotted holes on a bracket in order to adjust belt tightness.

However, there are some downsides to serpentine belts. One is that, since one belt controls multiple accessories, if it fails, you typically lose functionality of all the external engine components; there’s no more “oh, I can drive the car without power steering.”

And, when serpentine belts fail, there’s rarely the squeal of belt slippage to be the canary in the coal mine that you get with a V-belt system. Instead, they typically fail catastrophically. Either the tensioner itself can fail, or the bearing or other mounting component of one of the idler pulleys can fail (maybe you’ll hear a snotty metallic rattle from the bearing going bad), causing the belt to be thrown. But when something goes, because of the belt’s length and the number of things it wraps around, it can cause a lot of damage, taking the cooling fan, electrical connectors, and cooling hoses along with it.

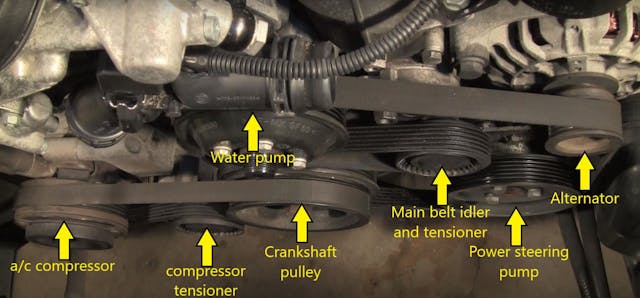

As a do-it-yourselfer, the big problem with serpentine belts has little to do with the belt itself—it has to do with the era of the car. Any number of things on modern cars that were easy to replace on vintage cars—alternators, starters, water pumps—are typically not easy to access, and the serpentine belt and its attendant idler pulleys and tensioner definitely fall into that category. Hell, I can’t even see them from under the hood in my 1999 and 2003 BMWs. Whenever you see a photo of a serpentine belt on the front of an engine showing the circuitous path it takes, it’s highly likely that components have been removed for the photo (in mine above with the yellow arrows and labels, the radiator, upper hose, and fan were removed). So, the ethos of “I’ll just throw a spare belt in the trunk and, if it breaks, I’ll change it on the road”—which works for vintage cars—isn’t really a good fit for cars with serpentine belts.

The best medicine is prophylactic maintenance. If you don’t know when the belt was last replaced, change it before a long trip. How long a trip does that have to be? Well, what’s the furthest from home you want to be when your belt tears out your power steering hoses? Read up on how much you need to disassemble on your particular model to change the belt. Think about combining it with other “while you’re in there” maintenance (e.g., if the radiator and fan need to come out, do you know how old the water pump is?). Although there’s usually a diagram of the belt routing either under the hood or in the owner’s manual, take a few good photographs.

Once you’ve released the tension on the tensioner and removed the belt, reach in and grab the idler pulleys. Try to move them on their bearings, then spin them. If there’s play or noise, replace them. They’re usually cheap. The tensioner, though, can be a little pricey if it’s hydraulic and you buy an original equipment part from a dealer. At least, that’s the case with the BMWs I own. Work the tensioner back and forth and judge if it feels stiff or has play and feels sloppy. Read up on an enthusiast forum regarding whether there are good aftermarket alternatives or if you’re best off paying for an OE part.

Or, go back to driving your vintage car where you really can just throw a spare fan belt in the trunk. Unless those bushings are soft.

***

Rob Siegel has been writing a column (The Hack Mechanic™) for BMW CCA Roundel magazine for 34 years and is the author of seven automotive books. His new book, The Lotus Chronicles: One man’s sordid tale of passion and madness resurrecting a 40-year-dead Lotus Europa Twin Cam Special, is now available on Amazon (as are his other books), or you can order personally-inscribed copies from Rob’s website, robsiegel.com.