Media | Articles

The “soft failure” of a dead alternator

I write again and again about “The Big Seven” things likely to strand a car (ignition, fuel delivery, cooling system, charging system, belts, clutch hydraulics, and ball joints, and yes, thing #0 is a flat tire). Although I mean it primarily with respect to road-tripping vintage cars, “The Big Seven” applies accurately to modern daily drivers as well, as long as you understand that, instead of actual ignition failures, you have failures of the crankshaft position sensor that the ignition relies on.

It’s instructive to divide things into “hard failures” and “soft failures.” Hard failures include a set of ignition points where the nylon block has snapped off, a dead fuel pump, a shredded belt, a bad clutch cylinder, and a broken ball joint. You’re not going anywhere until you replace the broken part. Soft failures could include cooling system and charging system problems. For example, if the engine temperature is creeping up in hot weather but the car isn’t leaking coolant, you can baby it by driving at low speeds for short stretches in order to get farther down the road and somewhere safe to look at it.

But the softest soft failure of all applies to charging system problems. How serious is it when that battery light comes on? How far can you drive? What happens if you ignore it?

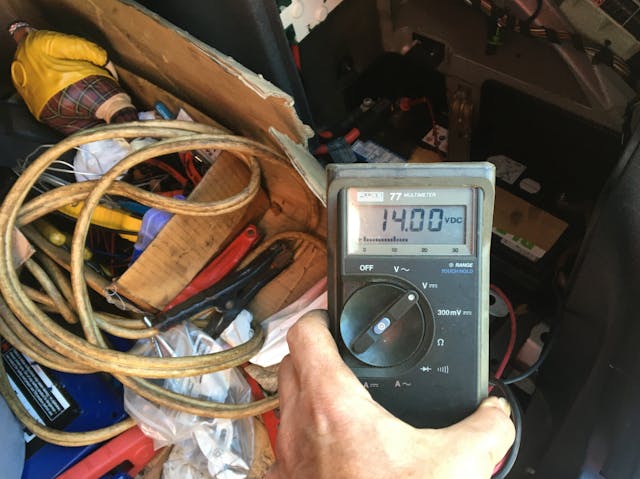

A car’s charging system consists of the alternator or generator, the voltage regulator (which can be external to the alternator or bolted to the back of it), the battery, and the wiring connecting them. The resting voltage of a fully charged battery (what you’d see if you measured across the battery terminals with the engine off using a multimeter set to measure DC voltage) is 12.6 volts. When the engine is running and the alternator is charging the battery, the voltage should increase by about 1 to 1.5 volts, so you should see what’s usually quoted as 13.5 to 14.2 volts. On vintage cars, the alternator is often anemic, so with the engine running, you may only see 13 volts, especially if the headlights and fans are on. Still, it should be a step above the 12.6V resting voltage. Conversely, modern cars with their digital engine management systems may sometimes run their alternators up into the 14.5- to 15-volt range. But the point is that the voltage should be higher with the engine running than it is with the engine off.

So, what happens when the charging system malfunctions? Sometimes nothing, at least not at first. It depends on the reason the system has stopped charging. If the belt broke, or the alternator’s bearings seized, those are hard failures, and any other component that’s also driven by the belt is no longer spinning, and that’s a problem. On a vintage car, a “fan belt” typically drives the alternator and the water pump (and, with it, the water pump-mounted cooling fan), so a seized alternator or broken belt will cause the engine temperature to head into the red, and fast, and this is a much more serious problem than the lack of charging.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

In a modern car with a “serpentine belt,” the same belt is used to run most of the engine accessories, including the power steering pump, so if the belt isn’t doing its job, in addition to it beginning to run hot, the vehicle will suddenly be difficult to steer.

Let’s assume that the alternator or regulator has an electrical problem, not a mechanical one. You’re driving, and suddenly the battery light comes on. Initially, there’s no other symptom. If you have a multimeter, or one of those $8 cigarette-lighter voltmeter plug-ins (which I highly recommend), the odds are overwhelming that you’ll see that, with the engine running, the voltage reading is 12.6 volts or less.

This is the instant necessary diagnostic for a charging system problem. If the battery isn’t getting 13.5 to 14.2 volts or thereabouts with the engine running, the charging system is not charging the battery, and the car will die.

When?

Well, that’s a good question. It depends on the era of the car and how well-charged the battery is. In a vintage (say, pre-1975) carbureted car, the electrical system is very simple. If you’re driving in daylight under clear skies (so no headlights on, and no wipers, fans, or other electric motors), really all the battery needs to do is keep the ignition coil firing the spark plugs and occasionally tickle the brake lights and turn signals. That’s it. The load isn’t more than a couple of amps of current. If your battery is in good condition, you can probably drive hundreds of miles that way. When the car dies (and it eventually will), if you can’t diagnose and repair the charging system failure, you can drop in another fully charged battery and keep going. If you have a trunk-mounted battery, you can even daisy-chain two batteries together with well-secured jumper cables to increase capacity. As soft failures go, it’s downright squishy.

If, on the other hand, you have a modern car—and by “modern,” I mean roughly post-OBD-II, with an electronic control unit (ECU) and multiple control modules—the car isn’t nearly as forgiving of running without a working alternator. Those control modules need to see a stable voltage. As the voltage drops, strange things begin happening. The car may act like it’s possessed. All the dashboard indicator lights may come on and off. The car may begin bucking instead of driving and accelerating smoothly. When this happens, you probably have only minutes before it croaks altogether. When you coast to the side of the road and try to restart the car, the odds are strong that you’ll turn the key and hear either the weak rrrrrr of a starter motor without enough juice to crank the engine over, or nothing at all.

Whether it’s a modern or a vintage car, if a non-functional charging system has drained the battery, what you can’t do is jump-start the car and expect to keep driving. Sure, jump-starting will spin the starter motor, and as long as the jumper cables are connected, your car will be leeching amperage from the battery supplying the jump, so it should start and run, but if the cause of the dead battery is that the battery isn’t being charged, jumping it won’t fix that, and I guarantee you the car will die again, probably within a mile or two. This is why you or someone else has to verify that the voltage with the engine running is higher than the resting voltage. If you call for roadside assistance and they don’t check this and instead merrily send you on your way, it can be dangerous.

The above is exactly what happened to my wife about 10 years ago. She took my 1999 BMW E39 528i sportwagon up to New Hampshire to go hiking with friends. On the drive back, the alternator died, and the 4000-pound vehicle eventually gave up the ghost. She wrestled it to the side of the road and called AAA. The AAA guy didn’t know enough to check the battery voltage—he just jump-started the car. She got another mile down the road, then it died again. Fortunately, she was somewhere safe. This time she had it towed to a repair shop.

So, the “soft failure” of a dead alternator is kind of a funny thing. Putting the battery light on the dashboard in context, if you see the oil pressure light come on while you’re driving, it means stop right now or your engine is going to make catastrophic and expensive sounds. If you see the temperature creeping toward the red, it means stop now if you want to prevent a warped or cracked head. If you see the “Check Engine Light” on but the car is running fine, it means when it’s safe and convenient, have a repair shop plug in a code reader to see what emissions-related event has triggered the light. In terms of urgency, the battery light is somewhere between the Check Engine Light and a rising temperature gauge. Depending on the age of the car and the electrical load, you may have 15 minutes or six hours until the car dies.

With that background, let me tell you this week’s dead alternator story. I was out on a mission of mercy, having a look at two early 1970s BMW 2002s—coincidentally both owned by women whose husbands had passed away, both looking for advice on selling the car, and both up on the north Massachusetts shore. After the second errand, I was heading home in my 2003 BMW E39 530i when I heard a little chirp and saw that the alternator light was on. I pulled into the right lane, prepared to stop if I saw the temperature climb, but the needle stayed right in the middle of the gauge. I was happy to see there was a rest area a few miles down the road. I pulled in.

The engine compartments in modern cars are tight, with components shielded from view, but I could see that the car’s serpentine belt was intact and still spinning all components, including the alternator. I had a multimeter with me, so, with the engine running, I put it across the terminals of the trunk-mounted battery.

It read just 12.2 volts. With the voltage that low, it was likely that the alternator had quit charging the battery before the dashboard light came on.

Damn.

It was a little after 5 p.m. I looked at the mapping application on my phone. I was 50 miles from home and headed into rush hour. I had some tools with me, but no alternator or regulator.

On vintage cars, when the battery light comes on, after checking the belt, the next thing to check are the connections to the alternator. It’s often as simple as a 50-year-old wire that broke off the main connection to the battery. If the car has an external voltage regulator, any of the wires connecting it to the alternator can have a broken connector at either end. Modern cars, however, usually have one thick battery cable and a single, molded, snap-on plug for the other connectors, and these are unlikely to be the cause.

I found some shade and thought about it carefully. My choices were these:

- I could make a run for it. But with rush hour ahead, the drive could take as long as two hours. With only 12.2 volts of battery charge, this was a poor bet. And the idea of leaving the safety of the rest area to take the car back up on the interstate where it was likely to die didn’t sit well with me.

- I could wait out rush hour, then make a run for it. That, however, would have me driving with my lights on, which would be certain to reduce battery life.

- I could drive to the nearest big box auto parts store (e.g., AutoZone), buy another battery, and double them up in the trunk with jumper cables. I thought about this, but batteries ain’t cheap these days, and the E39 takes a honking big battery that’s sure to be at least $180. And if I drove into nighttime, that still didn’t guarantee me safe arrival home.

- I could try to buy an alternator and replace it in the parking lot. If I was driving one of my vintage cars, this would be a slam dunk, as the alternator is easily accessible at the top of the engine compartment and can be removed in 10 minutes with two 13mm wrenches. However, in a modern car, the alternator is typically buried and is run off the serpentine belt. Even the act of releasing the tension on the belt is non-trivial. Last summer I’d replaced this car’s radiator, water pump, belt, and pulleys, and it was like one of those interlocking Chinese ring-and-rope puzzles requiring a special tool to remove the fan and viscous clutch, then sliding the fan shroud up and out of the way, which in turn required unhooking a bunch of plastic clips that attached hoses to the bottom of the shroud. I had some tools with me, but only a small fraction of what was in my garage. Plus, if a big box parts store had an alternator for the car, it would likely be a Bosch rebuild, and these have a terrible reputation.

- I could see if I could find a replacement voltage regulator and install it in the parking lot. In my late 1970s and ’80s cars, whose alternators have an internal voltage regulator, it’s usually the regulator that goes bad (the brushes wear down), and they can be easily replaced with the alternator in the car by unscrewing two Phillips-head screws. However, this was not a repair I’d done on the E39 before. I looked on my phone and learned that the regulator is behind a cover on the back of the alternator, and while replacing it is easier than replacing the alternator, it’s not trivial.

- I could have the car towed to the nearest repair shop. This is what my wife did 10 years ago with the E39 wagon. The bill for the alternator replacement was $600, and they used a Bosch rebuild. Ick.

- I could have the car towed home. I’d certainly have to pay for part of the tow, but then I could do the repair in my own garage and could have control over what parts went in it.

A tow home it is. Ain’t it great being 64 and feeling like you’ve got nothing to prove to anyone?

I called AAA and was quoted a three-hour wait. So I called Hagerty. I verified that I could use my Drivers Club towing benefit on a daily driver that was not on my Hagerty policy. Unfortunately, my benefit only included 20 miles of free towing, and the additional 30 would be a cost of $183. I wasn’t thrilled about it and thought briefly about making a run for it to at least get closer and thus bring the bill down, but I paid it, a tow truck was there in about an hour, and I was home about an hour after that.

(Incidentally, I posted this whole episode in near real time to social media. Three people with E39s responded with what happened to them when their alternator fried. One said he made a run for it. The battery lasted 25 minutes at night. Two others bought fresh batteries, dropped them in, and ran during the daytime with as small an electrical load as possible. One lasted two hours, the other nearly three. So, I likely could’ve made it with another battery. The cost would’ve been about the same.)

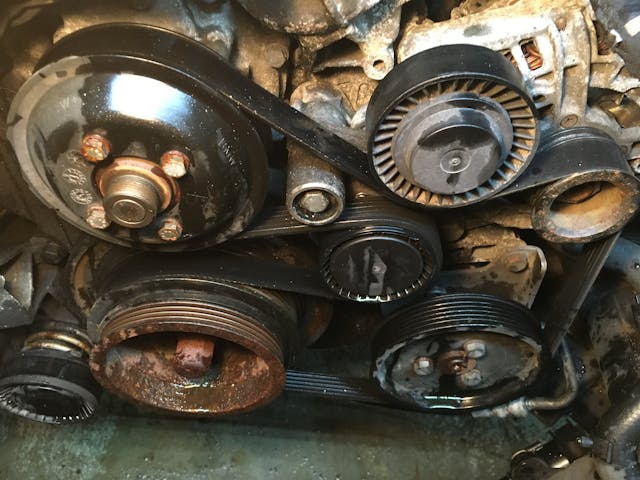

The next morning, I dove in. The alternator on an E39 isn’t really that deeply hidden; remove the airbox and there it is. Unbolting the power steering reservoir and swinging it to one side improves access.

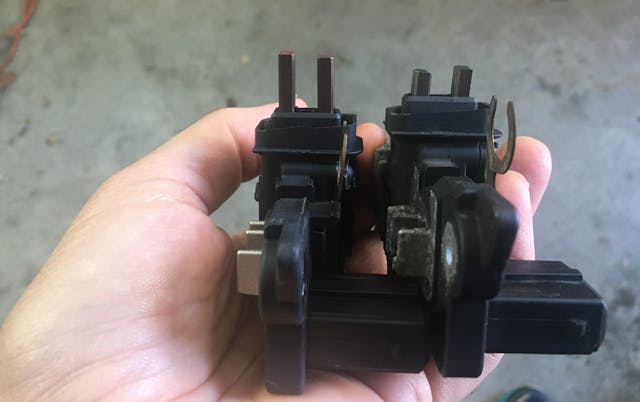

Rather than defaulting to replacing the alternator, I thought I’d try removing and inspecting the regulator. If the brushes were badly worn, I’d buy a regulator, but if they looked OK, the alternator was likely at fault and would need to come out.

I watched a video on removing the alternator’s rear cover. It gave me the general gist of it, but the nut sizes didn’t match what was on my car, and the video made no mention of the fact that one of the nuts is covered by a little snap-on piece that, to me, was indistinguishable from the plastic cover. Just resolving this took me nearly an hour. However, it did alert me to the fact that one of the fasteners holding on the cover was a Phillips-head screw in a deep recess, and owing to restricted clearance, the best way to reach it was with a Phillips nut driver turned by a wrench.

In total, in my well-equipped garage, it took me more than two hours to get the cover off the back of the alternator. Once it was off, it exposed the regulator, though it was difficult to tell where the regulator left off and other black plastic on the alternator’s rear began. The Phillips-head screws holding on the regulator were incredibly tight, and one of them began to strip. It nearly caused me to abandon the “just the regulator” approach and order a new alternator when I gave it one final push-the-Phillips-bit-in-as-hard-as-you-can-while-turning try, and it broke loose. Out came the regulator, allowing me to see the smoking gun of badly and unevenly worn brushes.

Unfortunately, when I looked at the slip rings the brushes ride on, I could see that the forward one had a visible groove worn in it.

Still, with a new Bosch alternator costing nearly $300 and a Bosch regulator only about $40, I thought I’d give it a try. I ordered the regulator. You can see how badly worn the old brushes really were.

There was just one issue. I wanted to give the copper slip rings a little cleaning by running a Scotch Brite pad over them, and to do that I needed to spin the alternator. I was hesitant to do it by running the engine, as I imagined the Scotch Brite pad catching and getting sucked into the alternator, so I needed to turn the alternator by hand, which meant releasing the tension on the serpentine belt, the thing I didn’t want to mess with unless I had to. Fortunately, I figured out that, rather than removing the fan and shroud and going in from the front, I could position a little breaker bar with the required 8mm Allen head bit on it and go in from the side. With the belt unhooked from the alternator, I could spin it—a necessary task to check for play and rumbling in the bearing.

The new regulator went on, I buttoned things back up, and tested the voltage … 14.0 volts. Yeah, baby.

Since this car has 200,000 miles on it, and since the alternator appears to be original, and since one of the slip rings is grooved, replacing the alternator is probably the smarter thing to do from a preventive maintenance standpoint than just replacing the regulator. However, as I’ve written, with the questionable quality of even new name-brand parts these days, I’m hesitant to take something that’s working and replace it with something that may not be as good. But now that I know the side-access-to-the-belt-tensioner-bolt trick, I may source an inexpensive used alternator and throw it in the trunk as a spare, as I now know that I could change it on the road if I had to.

So, there you have it. If you’re 10 minutes from home and the alternator light comes on, and the thing is still spinning, you can probably make it. But as I keep saying, there is a 100 percent probability that the car will die, and you really don’t want that to happen in an uncontrolled fashion. Choose wisely.

***

Rob Siegel’s latest book, The Best of the Hack MechanicTM: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and assorted automotive mayhem, is available on Amazon. His other seven books are available here, or you can order personally inscribed copies through his website, www.robsiegel.com.

You are entirely right regarding the risks of “refurbished” alternators at parts stores. I replaced the alternator on a relative’s Suzuki SX4 3 times in one year, each time getting a “new” one from the warranty of the previous. Each time following the diagnostic procedures with a meter, amp clamp and load tester, checking the excitation and battery sense terminals.

Regarding making the right choice about a battery light…

I was driving an ’84 Bombardier Iltis home on one of the last days of the season when the voltmeter on the dash started flickering towards the upper end (over 30V on a 24V system). I didn’t think much of it until it got dark and I turned the lights on to see the voltmeter at battery voltage (24V). Being an old carbureted army jeep, I thought I could get home on just the batteries. Until, that is, I stopped at a light and saw the smoke coming from under the hood.

Turned out the B+ alternator output wire had broken off the alternator, and a large capacitor designed to protect the system from surges literally exploded.

Refitting the B+ wire was easy, but the running voltage was now 32V at idle, and climbing with engine speed. Current output was almost 30A at idle.

I had to choose between a tow (3 hour minimum wait time), driving at night without an alternator, or driving with an evil over-charging alternator. I chose the last option and drove the 2 hours home with all the accessories on. It ran beautifully, lights brighter than ever. Until it stalled. Twice. I had to adjust the ignition timing to restart it.

Needless to say, the regulator was cooked – literally a crispy black brick, the batteries were hot and bulging, the engine starts only if you advance the ignition and pray, and the electric fuel pump has an erratic chatter to it.

I made the wrong decision, and now the winter project will be assessing the damage.