Media | Articles

The Armada Springs a Leak

After sealing up the exhaust in my recently-purchased 183K-mile 2008 Nissan Armada well enough to get it through the second-most stringent state inspection in the country, I dealt with noise from the serpentine belt. The problem turned out to be bad bearings on the timing chain tensioner, but there was also noise from the power steering pump, which led me to fix a leak from one of the PS hoses by replacing the constant-tension spring clamp with a worm-screw type clamp that could be tightened. That wound up slippery-sloping into fixing other under-engine leaks (the power steering uses automatic transmission fluid, so I needed to be certain the leaks were from the PS and not from the transmission), and that led me to a place I didn’t expect to go.

Fluid leaks should be looked at in terms of both substance and severity. That is, for lubricants, you can grossly triage them into drips, patches, puddles, and gushes. Drips are isolated “marking their territory” dots. Patches are fried-egg-sized stains on the garage floor. Puddles are things that have enough depth that you can swipe a finger through them and actually move fluid like Moses parting the red sea. Gushes are where you actually see fluid streaming out of the car and can follow it directly back to its source. Obviously you’d be foolish to drive a car that’s gushing any fluid further than down the driveway and into the garage, but the others are more of a judgement call. Anyone who owns a vintage car knows that it’s in their nature to leak engine oil, gear oil, and transmission fluid, and enforcing a zero-leak policy may not be possible. My Lotus Europa leaks fluid from the transaxle in quantities between a patch and a puddle, and I’ve replaced the transaxle seals twice in a misguided attempt to squelch it, only to learn in the forums that, basically, they all do that, and loving the car means living with its incontinence, placing a drip pan under it, and topping it up with a frequency usually reserved for engine oil.

But substance—which fluid is dripping—is critical. There should be a zero-leak policy with gasoline. Weeping a little gas isn’t acceptable. Any fuel leak should be found and fixed immediately, otherwise you risk your vehicle burning and you dying.

I regard coolant leaks as a big notch back from fuel leaks, but they’re still unacceptable. If coolant is leaking, even dripping, something is failing, and you can be certain that it’ll get worse over time. It won’t kill you, but it can kill your car by depleting the engine of coolant to the point where it overheats and warps or cracks the head. Driving a car that you know is leaking any amount of coolant any more than around town isn’t dangerous, but it’s dumb. Don’t do it. In my BMW-centric world, where I road-trip 50-year-old cars thousands of miles and daily-drive 20-year-old cars with plastic-laten cooling systems that crack at any moment and dump the coolant, I’m hyper-vigilant about cooling leaks. The cause could be a loose hose clamp, or corrosion on a metal coolant neck not allowing a hose to seal, or a bad water pump seal, or an actual hole in the radiator or heater core, or, in a modern car, failure of a plastic component. Visual inspection with the engine running usually reveals the source. Pressure testers that screw in in place of the radiator cap can also be helpful if the leak only occurs at operating temperature.

So, back to the Armada. There were two other places where the rubber PS hoses were leaking where they’re pushed over metal lines and secured with spring clamps. The worst of them was where two lines ran through the engine compartment on top of the left frame leg. It was the lower one that was leaking, and the upper one blocked the access to getting vise grips on the spring clamp. I wound up having to remove the inner fender liner in order to get at it from the side. As with the first PS leak, installing tighten-able worm clamps stanched the leak.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

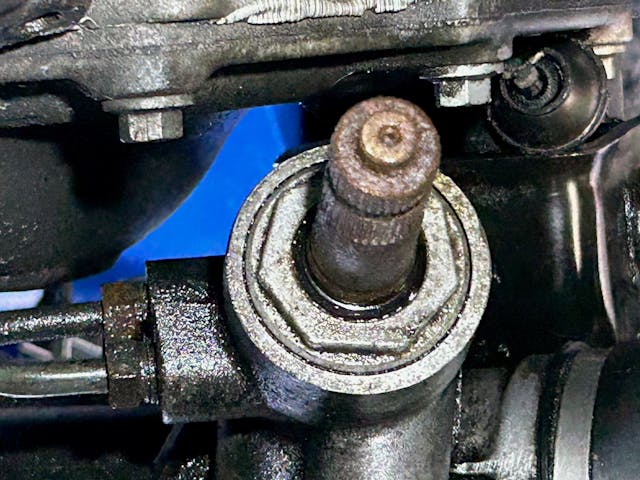

The remaining PS leak took me a while to find. A drip kept forming below the steering rack on the frame. To find the source, I had to lie under the car with the engine running and watch. Unfortunately, it’s coming from where the input shaft goes into the top of the steering rack, and replacement of the seal likely requires removal of the rack, which in turn requires removal of the front differential. Further, the seal is in the middle of—get this—a seven-sided nut for which I’ve yet to locate any reference to a removal tool. Fortunately, it’s a small leak, so for now I’m going to let it go.

But while I was under the Armada’s nose, I found, to my surprise, drops of coolant at the bottom of the radiator and stray ones higher up. When I bought it, I knew about the wetness that was likely from the power steering, but the coolant leak was not something I was aware of.

It turned out to be leaking from two places. The first was from below the radiator cap, where a thin hose attaches that feeds the overflow tank. Like the PS hoses, it was leaking from the spring clamp, so I replaced it with a worm clamp, but it continued to leak from the brass fitting to which the hose was attached. At first, I didn’t understand what I was seeing—the fitting seemed like it swiveled. Then I realized that there had originally been a little plastic coolant neck there, it had snapped off (a very common problem on plastic radiators), someone had jury-rigged it with a screwed-in brass fitting and sealed it with Teflon tape, and it was now loose and leaking.

I first tried Permatex Thread Locker. That leaked, so I went to Gorilla Glue. That leaked too, so I was prepared to go nuclear with J-B Weld when I discovered a second leak.

This one was from someplace more serious—where one of the automatic transmission lines went into the plastic tank at the bottom (the radiator also acts as a transmission cooler, as it does on many vehicles). It wasn’t leaking from the hose, so replacing the spring clamp as I’d done elsewhere wouldn’t matter. It looked like the leak might be coming from a seal behind the fitting that ran through the plastic tank, but my attempt to loosen or tighten the nut only caused the plastic to flex and the leak to increase.

In addition, one of the things I read about the Armada is that the radiator’s internal transmission-cooling plumbing eventually cracks, allowing ATF and coolant to intermix. This creates the dreaded “strawberry milkshake” that causes the transmission to fail. I checked the date code on the radiator, and it was original to the car. Taking these three things together, I would’ve been an idiot to not replace the radiator, and as I often say, I try not to be an idiot. Seriously—it’s one thing for something to break with no warning, and quite another to be stranded and sit there thinking, “Yeah, I should’ve replaced that.”

As with everything I do, I looked at the cost. Folks who routinely tow big trailers install a separate heavy-duty transmission cooler. Others replace the radiator, either with the original Nissan part, or a less-expensive aftermarket choice, or an aluminum one. RockAuto has several cheap radiators, but these things are big, and with shipping they came to about $150. The correct Nissan radiator with its known shortcomings could be had on eBay for as low as $180. These days the world is full of decently-priced Chinese-made aluminum radiators. I’ve used them in a variety of cars. The weld quality varies from decent to cringe-worthy, but I’ve never had one leak. Whether or not to use one is a question of fit and vibe. I think they look completely out of place in my beloved BMW 2002s, and besides, they’re too thick to use without deleting the original cooling fan, which I refuse to do, but I have one in my Lotus Europa and use them in some of the later BMWs. The Armada forum said that there’s plenty of room for a three-row or even a four-row aluminum radiator, but fit-wise, the fan shroud needs to be fettled with.

I would’ve preferred to buy an aluminum radiator on Amazon so that I could return it cost-free if it wouldn’t fit, but the cost there was $250 for the same radiator that was $185 on eBay. Then I found a new eBay vendor with zero feedback selling the same radiator for $165 (drop-shipped from the same port in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, as nearly every other seller). There was the risk that the vendor wasn’t real, or the radiator was damaged or open-box, but I clicked and bought, and I was relieved when an intact new radiator arrived two days later in a sealed box.

As the box sat in my kitchen, I thought, “Damn, this thing is big.”

Replacing a radiator on a vintage car consists of draining it, removing the upper and lower hoses, removing the four bolts holding it to the nose, and done in 15 minutes, tops. But on newer cars, it’s typically far more complicated. On the modern BMWs that I’m familiar with, it’s like one of those interlocking rope-and-ring Chinese puzzles, where an odd dance needs to be done with the fan, the shroud, and the expansion tank. On the Armada, the fan and shroud were straightforward, but it turns out that the power steering fluid cooler and the A/C condenser are attached to the front of the radiator, so the dance involves unbolting the condenser, then tilting the radiator forward so you can unbolt the PS cooler.

Despite its size, I expected the original plastic-tanked radiator to be fairly light, but a combination of fluid remaining in it and it sticking to its rubber mounts made it a “don’t do that” to my 65-year-old back, so I elicited help from one of my kids to muscle it up and out. I test-fit the shroud on the new radiator and did some cutting to get it to seat around its upper tank.

When you replace a radiator, there’s the question of how much of the rest of the cooling system you should prophylactically replace, even if there’s nothing wrong with it. If the water pump or the thermostat or the fan clutch go south on me, I’m certainly going to be pissed that I didn’t just replace them while they were all accessible, but the fan clutch feels fine, there’s no play or leakage in the water pump pulley, and the car warms up perfectly. I did, however, inspect the hoses at the front of the engine and found that the aluminum neck to which the upper radiator hose is attached was badly corroded. I replaced the hose and cleaned the neck. The lower radiator hose looked OK, but for symmetry I replaced it at the same time.

Dropping the new radiator in wasn’t nearly as bad as removing the old one, as I had gravity on my side, but getting the cooler and condenser reattached was challenging. I dropped the condenser attachment bolts down into the nose multiple times and had to fish them out with a magnetic wand.

When the radiator, shroud, and fan were all installed, I spun the fan by hand and heard it hitting the shroud due to lack of clearance on the left side. I could’ve pulled it back out and trimmed that side, but the only bolt-on attachments are at the top, so even if I created clearance, there was nothing to hold it in place. So in true Hack Mechanic fashion, I installed a very stout zip tie at the bottom corner that pulled it where it needed to be.

I did the drive-park-check cycle a few times to be absolutely certain no coolant was leaking and the only remaining leak was the trickle from the steering rack’s input shaft, then deemed it roadworthy.

So in terms of the Armada’s punch list, that leaves the front struts. I’ll get to that next week.

***

Rob’s latest book, The Best Of The Hack Mechanic™: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and assorted automotive mayhem is available on Amazon here. His other seven books are available here on Amazon, or you can order personally-inscribed copies from Rob’s website, www.robsiegel.com.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I’m guessing the Armada will provide endless new stories for future repair articles!