Media | Articles

Knowing when to back away from a repair

I’m going to introduce today’s topic—knowing when to back away from a repair—by telling four short stories.

The first is the time I didn’t back away. I bought my first BMW 2002 shortly after my then-girlfriend and now-wife and I moved to Austin 40 years ago. Its transmission was whiny. I checked the fluid level and found that it was dry. I filled it, and the whine went away, but in the morning, all the fluid was on the driveway because the transmission end cover was cracked. No problem, I thought; I’ll just replace the cover. I removed the transmission, began disassembling it, and learned that most the guts are suspended from the end cover, so replacing the cover requires going through most of the steps you’d take to rebuild the transmission, and this requires special tools.

In an act that was equal parts youthful confidence, commitment to task, intestinal fortitude, and utter foolishness, I bundled the transmission into my wife’s VW bus, parked outside BMW specialty shop Phoenix Motor Works in Austin, and ran inside and borrowed tools from owner Terry Sayther, who, at the time, I barely knew (Terry and I still laugh about this). While I had the thing apart, I replaced a munching second gear synchro. I did get it back together, and it was leak-free, but two months later second gear was munching again because I did a poor job measuring and shimming.

The second story is about the birth of my wife’s and my first child. This may seem like a wild digression, but it’s actually germane. Ethan was a big baby, and after a long labor that wasn’t progressing, the gray-haired seen-it-all-before obstetrician tried a forceps delivery. It wasn’t successful. He tried again. On the third attempt, he tugged hard enough that I watched my wife’s body move on the exam table. The doctor calmly laid the forceps down on the table, thought for a second, and said one word, “No.” It was a moment I’ll always remember. In my wife’s case, “no” meant a C-section, but in the larger sense, here was a senior experienced professional who went as far down a path as he could but knew when to stop and take another approach.

No. 3 is a folk tale of unknown origin. The gist of it is that if you go into a cave and find a beast inside, you need to be prepared to battle it to the death. If you’re not, you should back slowly out of the cave.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The last story is a Klingon parable from Star Trek: The Next Generation. A storm is approaching the city. All seek shelter except a young Klingon warrior. He says that he is not afraid and will stay outside and make the wind respect him. The storm comes. He is killed. Moral: The wind does not respect a fool.

The necklace to be formed from these seemingly disconnected literary beads is that we try to kick many things in life, including do-it-yourself automotive repairs, between the goalposts of “that was no big deal” and (to quote Rick and Morty) “I was not in control of that situation.” In the case of my 2002 gearbox all those years ago, I’ve never disassembled another transmission since. Now I just swap them, which is what I should’ve done back then had I known better. On the other hand, nothing hammers home knowledge like actually doing something and coming away from it muttering, “Well, I’d never do that again.”

It’s rare that, having ventured into a repair, I’ll either back out of it or feel like I’d never do it again, but there have been a few examples.

When I had my 1982 Porsche 911SC (sold 12 years ago and still badly missed), it began leaking oil. People refer to vintage Porsches as “air cooled,” but they’re actually air and oil-cooled. There’s a nose-mounted oil cooler, a wax thermostat under the right front fender, and oil lines connecting them that run the length of the car.

One of the leaks was coming from one of these lines that’s a rubber hose crimped onto an aluminum tube. I was able to undo the end that’s attached to the engine, but the big 36mm nut holding the other end to the oil thermostat wouldn’t budge. The nut is steel, the thermostat’s aluminum, decades of corrosion of dissimilar metals fuse them together, and the tight confines of the fender cavity make it difficult to put heat and leverage on the nut. I bought the special 36mm flare-nut wrench, put it on the nut, and applied leverage, but the wrench slipped and smacked the inside of the fender. I found myself channeling the obstetrician who delivered my son—I literally put the wrench on the garage floor and said “No.”

I read up on the problem on the Pelican Parts 911 forum and learned that the thing to do is to drop all of the oil cooler plumbing—the cooler, thermostat, and the lines connecting them—as a unit. With everything laid on the floor, it gives you the clearance to safely apply heat and leverage. But the next thing I saw were photographs of snapped-off oil lines and shattered thermostats.

I backed slowly out of the cave.

I addressed the problem by replacing only the crimped-on rubber portion of the line that was leaking. First, I verified that it wasn’t a high-pressure line and was instead a scavenging line with under 100 psi. Next, I cut off the external part of the old crimp fittings with a Dremel tool, then carefully cut away the old rubber hose. This exposed the undamaged barbed fittings underneath. I sourced a section of correctly sized hydraulic hose from a hydraulic supply shop, temporarily held it in place with high-quality T-band clamps, then drove the car to the hydraulic shop, where they used crimp-on clamps good for thousands of psi.

The remaining oil leak in the 911SC was from the oil return tubes that allow oil to drain back from the heads into the crankcase. These were originally installed before the heads were put on, but you can buy aftermarket tubes with two collapsible sections that expand outward and have a locking clip. The idea is that you cut up the old tubes, remove them, install the new seals, and slide and lock the new tubes in place. I bought a set but found that I could only reach two of the original tubes; the others were blocked by the exhaust manifolds and heater boxes. I looked carefully at the studs holding these to the heads and found that, due to age, rust, and heat, they were withered stubs, a fraction of their original size, they would certainly snap with a horrifying little tang as soon as any leverage was put on them, and no amount of heat or penetrating oil would forestall that ineluctable fate. This time, I didn’t even enter the cave—I didn’t even consider undoing the exhaust manifolds. I replaced the two tubes that I could reach and stopped. Fortunately, they happened to be the two that were leaking the worst.

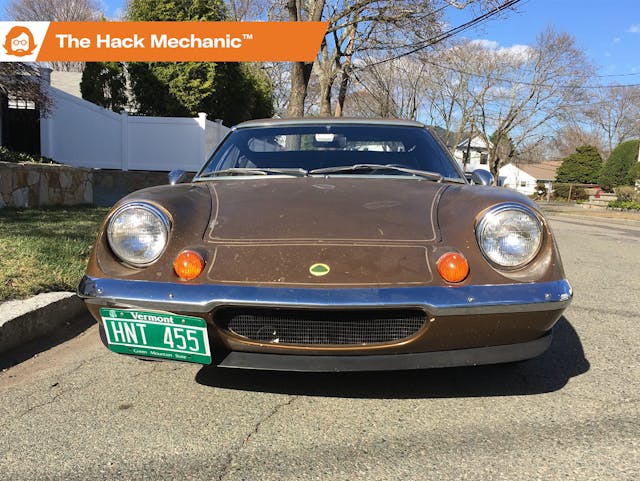

Last summer, I went through the episode with the mouse-infested truck, in which I drilled holes in the outer housing of my 2008 Silverado’s heater box, extracted a large mouse nest and a desiccated carcass, and flushed the box with cleaner rather than go to the likely 20 hours of work needed to remove the dash to get the heater box out. In that article, I said that I would have no hesitation going through the effort to remove the heater box in a beloved passion vehicle, but for a truck that I regarded as a utility vehicle, it just wasn’t worth the effort to me. Last fall, those words came back to haunt me when I noticed a strong mouse smell in my Lotus Europa. The smell seemed to lessen substantially when I blocked off the air flow through the heater box. I snaked my inspection camera inside the heater box, and while I didn’t see any mouse detritus, the air-flow-while-driving test seemed pretty conclusive.

Thus, one of my winter projects has been to remove the Europa’s heater box and clean it. Like everything else about the car, the heater box is a bit unusual. It’s more of a tray with a back than a box. The open section of it faces forward into a cavity in the car’s fiberglass body through which air flows. The box has the usual retinue of control cables that move flaps, and, of course, two heater hoses. But it’s way smaller and way less complicated than the one in the Silverado.

So, I had at it. On paper, it doesn’t sound like removing the heater box is all that difficult. The cables and hoses have to be disconnected. The glovebox has to come out. The wiper motor needs to be loosened and swung out of the way. Then you unbolt the box from the firewall and slide it out to the right. Pretty standard stuff.

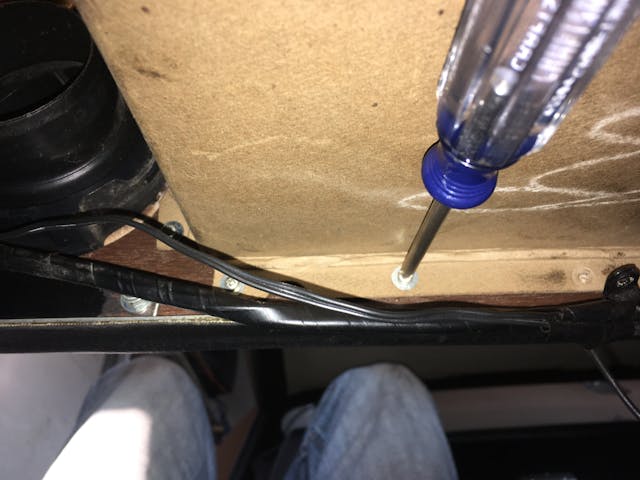

Except for the it’s-a-Europa-so-it’s-weird factor. The glovebox is basically cardboard that’s painted black in the front, and it’s held to the back of the dashboard with eight little Phillips-head screws that were driven in place before the dashboard was installed in the car. Getting at the screws without removing the dashboard requires what is perhaps my least-favorite mechanic’s position—lying upside-down with your head in the footwell and your legs draped over the seat. I did get the glovebox out, but my back wasn’t the same for days.

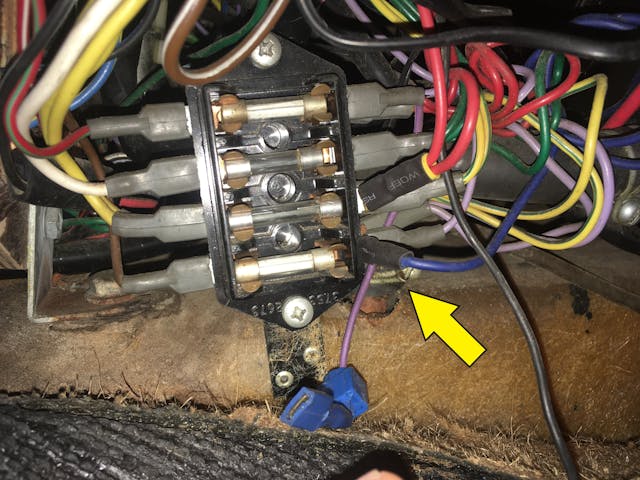

Further, the heater hoses come up from the transmission hump, and the one on the right emerges directly behind the fuse box. The heater hoses are rock-hard and likely original to the car. On the one hand, this makes replacing them a good idea, but it also means that they’re not going to come out without a fight, and the space to work is very tight. This car, astonishingly, has been virtually free of Lucas gremlins, and the thought of disturbing the wiring gave me pause.

Still, in for a penny, in for a pound, right? The fuse box sits behind the right-side panel of the console. The panel is such thin plastic that, when I’ve needed to check or change fuses, I’ve just bent the corner of it back, and it’s now starting to split. So as not to damage it further, I removed the console.

And when I did, I found a mouse nest—not a big one, and there were no mouse remains inside, but it was still quite fragrant.

And so, with no direct evidence of mouse contamination in the heater box, and with clear evidence of it under the console, I halted Operation Yank The Lotus Heater Box. The beauty of this is that I haven’t yet done anything to make the car un-drivable. When spring comes, I can drive it and see if the mouse smell is still there and if it still seems to be coming from the heater box. If it does, I can resume the operation. If not, I can button things back up.

There’s no shame in backing away from a repair. Maybe you are in over your head. But maybe “no” just means “not this way” or “not right now.” Remember: A snapped exhaust stud does not respect a fool.

***

Rob Siegel’s new book, The Best of the Hack MechanicTM: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and assorted automotive mayhem, is available on Amazon. His other seven books are available here, or you can order personally inscribed copies through his website, www.robsiegel.com.

Always remember:

WE DO THIS NOT BECAUSE IT IS EASY, but because we thought it would be easy.