Media | Articles

Dead alternator. Again. This time in the RV

Just two weeks ago I wrote about my little VW Eurovan-based Winnebago Rialta RV, saying that owning an older RV means having all the problems of an old car combined with those of an old house. In that piece, I wrote, “The Rialta forum on Facebook is full of posts from people saying, ‘We just bought our Rialta, we were so excited, we flew out to pick it up and drove it home, and all these things went wrong.’ I’m always surprised that people are surprised at this, as most of these RV-dies problems fall into the first five of “The Big Seven” things most likely to strand any older car that I’ve written about for years—they’re usually fuel delivery issues, ignition issues, cooling system issues, charging system issues, or belts.”

So, funny story.

My wife, Maire Anne, and I were taking a little two-day trip in the Rialta up to a campground on Boston’s north shore to celebrate our 38th anniversary. I’d just completed a good round of work on it to repair the issues that reared their heads on our last trip—replacing the leaky toilet, getting the shower drain pump to work, and coaxing the central locking system back into functionality. During the hour-long drive, we talked about how, while I felt pretty good about these short trips, if we were going to consider taking the rig on a big western road trip, it really needed a systematic push on the first five of “The Big Seven.” Last year, I wrote about how I’d replaced the failing coil pack, and had bought a new OEM fuel pump and a voltage regulator, but how the issue of slipping quality of new parts these days made me circumspect about replacing good working parts, so having the new parts in the cabinet as spares felt like the right thing to do for now. It’s a tough call. The fuel pump, for example, is inside the gas tank, and access requires unbolting the driver’s seat and pulling up the rug and pieces of the shifter surround—not exactly an easy roadside repair, but also something I’m hesitant to do at home when there’s nothing apparently wrong with it.

We had a lovely day at Plum Island, a 12-mile-long barrier beach that’s right across a narrow inlet from where we got married in 1984. We then headed to the Salisbury State Reservation campground for the first of our two nights.

Unfortunately, it was 90+ degrees out, and the campground had zero shade. I drew the window blinds, connected the Rialta to shore power, and turned on the roof-mounted air conditioner, but it was fighting a losing battle against the sun, and Maire Anne and I were sweating and uncomfortable. I started the engine and turned on the Rialta’s generally excellent cabin-and-coach vehicle A/C system, and the interior began to cool off.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

But when I looked at the cigarette-lighter voltmeter (I rarely drive farther than the grocery store these days without a cigarette-lighter voltmeter plugged in), it was reporting only 11.5 volts. As I’ve written many times, a battery’s resting voltage is 12.6 volts, and when the alternator is charging the battery, it should increase 1–1.5 volts, or about 13.5–14.2 volts. If it doesn’t—if it stays at 12.6 volts with the engine running—it means that the alternator isn’t charging the battery, which means that the vehicle will die. If it’s substantially lower than 12.6 volts, like the 11.5 volts I was reading, it means that the electrical load—in this case from the air-conditioning fans—will drain the battery even quicker.

I actually wasn’t terribly alarmed. The alternator in the Rialta has been a little weak since I bought the rig five years ago, and sometimes it won’t charge until the engine RPM comes up. As I described in my piece a few months back, about how having an alternator die is a “soft failure,” most cars built after the mid-1970s have an integral but replaceable voltage regulator that contains the brushes, and often the problem is simply that the brushes are worn down—and if that’s the case, replacing the pack will usually make the alternator spring back to life. (That’s what I did when the alternator in my 2003 BMW E39 530i died back in July). So, when I noticed this behavior in the just-purchased Rialta five years ago, I bought a voltage regulator to have with me, just in case. Two years ago, before Maire Anne and I began using the RV for summer fun, I resolved to install the regulator, assuming it was the same two-screw job as in an old BMW. I found that, not unlike the BMW E39, the regulator is behind a cover on the back of the alternator, but owing to clearance issues, there’s no way to get the cover off without removing the alternator from the car, and since the problem didn’t appear to be acute … well, you understand.

So yeah, I who prattles on and on about the necessities of performing prophylactic maintenance on a vintage car, and how you’re an idiot if you head off on a road trip with a known problem, had been doing that with the alternator for five years. I just had become used to it because the problem hadn’t gotten any worse.

To deal with the heat, Maire Anne made the excellent suggestion that we simply head down to the beach, where it was likely to be a lot cooler. So, we disconnected from shore power and began driving the maybe 200 yards to the beach.

That’s when the alternator warning light came on and stayed on. Even with the A/C off, the cigarette-lighter voltmeter showed a little under 12.6 volts, and the voltage did not increase as I revved the engine.

OK, now I’m alarmed.

Of course, out of all the places where this could happen, this was a pretty nice one. We were staying overnight in a campground a stone’s throw from the beach, and we were only perhaps an hour from home, as long as we missed rush hour. Still, a dead alternator is guaranteed to cause the battery to run down at some point, so everything in our mini-vacation grounded to a halt while I looked on my phone at the weather forecast and considered what to do.

I was blessed by being able to troubleshoot at the edge of a beach parking lot overlooking where the Merrimac River empties into the Atlantic. The sun was out, and the cool ocean breeze was heavenly. Maire Anne snapped the photo at the top when I donned my Tyvec suit to crawl under the Rialta and check if a wire or connector had pulled off the alternator (it hadn’t). You can laugh at my fashion-forward mashup of Tyvec and Tevas sandals, but given that I was skootching under the car on sandy hot asphalt, the Tyvec was as welcome as a rubber glove during an oil change.

When the alternator died in the BMW E39 two months ago—and by utter coincidence, that was just a few miles from where we now were—I was in a highway rest area. The E39 is a newer, more luxurious, control-module-laden car that has a reputation for wigging out when battery voltage gets low. So, with that car, I decided that the odds of making it home through rush-hour traffic, before the car died somewhere far less safe, weren’t great and called for a tow.

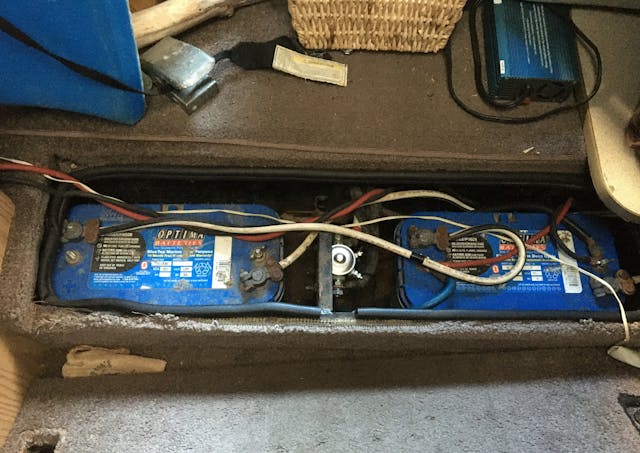

However, the Rialta is a different beast. In the first place, all the RV accoutrements notwithstanding, it’s an older, simpler vehicle that’s likely to drain the battery slower than the E39 (as long as it’s driven during the daytime with the wipers and the air conditioning off) and likely to be more tolerant of low battery voltage. But much more significant is the fact that, like any RV, it has two big coach batteries that power the RV systems, and there are ways to tie them to the vehicle battery, creating triple the battery capacity and thus, in theory, triple the amount of time before the vehicle coasts to the side of the road.

Many RVs, including the Rialta, use the alternator to charge both the vehicle battery (the one that cranks the engine over) and the coach batteries while driving. But when you’re at the campground and plugged into shore power, an integrated on-board battery charger charges the coach batteries but not the vehicle battery. In addition, if the vehicle battery runs down, there’s an “aux battery” switch on the dashboard that you can use to essentially self-jumpstart the vehicle battery with the coach batteries.

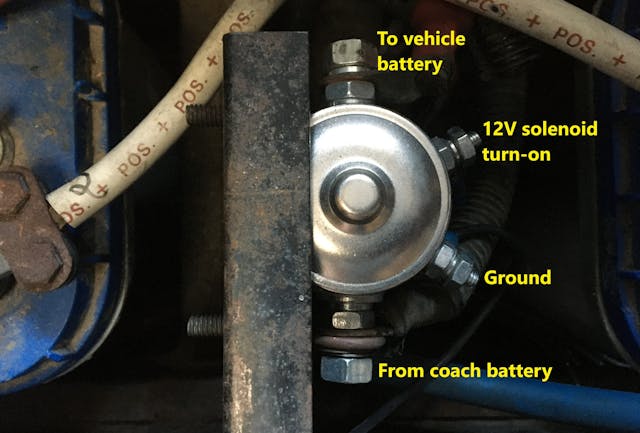

All of these machinations are accomplished by an isolation solenoid in the coach battery compartment. This is basically just a beefy relay, big enough to handle the hundreds of amps of peak current that may flow through it when you use the “aux start” switch and crank the starter motor. Like any relay, it has the low-current electromagnet part and the high-current switched part. The small terminals are for the low-current electromagnet. Connect one of them to ground and feed the other one 12V, and it energizes the internal electromagnet, which slides the solenoid, which closes the switch and connects the two large terminals together. So, when the “aux start” button is pressed, it sends 12V to the small terminal and ties the vehicle battery and the coach batteries together. When 12V is absent, the batteries remain separate.

I’d replaced the isolation solenoid last year, so I knew where it was and had a good idea how it worked. When I hit the “aux start” switch, I could hear the solenoid click, and when I put my multimeter across the vehicle battery and Maire Anne held in the switch, I could see the voltage come up slightly as the vehicle battery was reinforced by the two coach batteries.

But what surprised me was that I didn’t, in fact, need to do anything to tie the coach and vehicle batteries together while driving—when the engine was running, the solenoid was already in the clicked-on position. I realized that this was likely due to the fact that it’s this solenoid that lets the alternator charge all the batteries as you’re headed down the road. The fact that the alternator wasn’t charging anything didn’t matter; the batteries were still tied together as long as the ignition was on. I did, though, need to jumper the solenoid into the “on” position in order to get the Rialta’s on-board battery charger to charge the vehicle battery overnight.

Having figured all that out, I relaxed a bit, and that evening, Maire Anne and I had an absolutely first-rate night-before-our-38th-anniversary meal at Sea Glass, a very nice restaurant right on Salisbury Beach with floor-to-ceiling windows. We drove the mile back to the campground, reconnected to shore power, jumpered the solenoid, verified that all three batteries were getting charged, and called it a night.

That evening, it rained, so in the morning we waited a bit for the skies to clear to remove any possibility we’d have to turn on the headlights and wipers, then made the hour-drive home without incident. The voltmeter never dropped below 12.4 volts. As we were driving under sunny skies, it occurred to me that, in addition to the three batteries being tied together, the solar panel I’d installed on the roof to be certain that the RV’s refrigerator stays cold while we’re at the beach was feeding juice to all three batteries. In other words, as long as there wasn’t a big electrical load from wipers and fans, I could probably have driven the RV hundreds of miles with the dead alternator. So, it probably wasn’t necessary to cut our trip short. But still, I would’ve hated to be wrong.

We and the RV are now back home. Removing the alternator doesn’t look too difficult, though access is poor, as it often is in a snub-nosed van with a short hood and much of the engine angled beneath the body of the car. Videos point to needing to remove the electric cooling fans on the radiator to gain enough clearance to lift the alternator out. Bosch rebuilt alternators have a pretty spotty reputation, so I think I’ll inspect this one, and if the bearings are quiet, try replacing the voltage regulator—as I did with the BMW E39—and see how it does. And yes, having this happen may just nudge me toward installing that brand-new fuel pump that’s been sitting in the cabinet.

The real question is, why did two alternators on two cars die within two months within two miles of the confluence of the Merrimac River and the Atlantic Ocean? Is there some “Merrimac Triangle” effect, some esoteric mix of old industrial pollution hitting salt water that causes charging systems to shred? If I find out, I’ll let you know.

***

Rob Siegel’s latest book, The Best of the Hack MechanicTM: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and assorted automotive mayhem, is available on Amazon. His other seven books are available here, or you can order personally inscribed copies through his website, www.robsiegel.com.