Media | Articles

Broken Bolts and Unrealistic Expectations

There’s a classic Monty Python routine called “How to Do It” where they issue laughably simplified explanations on how to do very complex things (“Today we’re going to learn how to build box-girder bridges. But first, here’s Jackie to tell you how to play the flute: ‘Well, you blow here, and move your fingers up and down there.'”) I come back to this time and time again because it tracks with just about anything that requires expertise someone else has that you don’t.

Witness broken bolts. I’m not sure there’s any aphorism truer than the one that says, “every 15-minute repair is one broken bolt away from being a three-day job.” Yet there are—reportedly—tricks to removing them that put you back on track.

Allow me to digress for a moment. In a recent issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine, Matthew Crawford—author of Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry into the Value of Work—wrote a piece commemorating the 50th anniversary of Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry Into Values. I’ll freely admit that I read ZATAOMM when I was in college, and that I re-read it (and read Matt Crawford’s book) while I was writing Memoirs of a Hack Mechanic 12 years ago. I’ve never met Matt, but he and I (and many of you) are clearly cut from the same cloth where we enjoy working on cars because we find it fun, because it saves money, and as Crawford says, because it makes us “master of our own stuff.”

Where was I? Oh. Broken bolts. Right. One of the reasons I re-read ZATAOMM was that I recalled a chapter titled “Stuckness,” and wanted to reference it in a chapter of my book where I enumerated several techniques for removing seized bolts. Imagine my disappointment when I found that the, uh, nut of Robert Pirsig’s chapter on “Stuckness” was this useless train wreck of words:

“Stuckness shouldn’t be avoided. It’s the psychic predecessor of all real understanding. An egoless acceptance of stuckness is a key to an understanding of all Quality, in mechanical work as in other endeavors. It’s this understanding of Quality as revealed by stuckness which so often makes self-taught mechanics so superior to institute-trained men who have learned how to handle everything except a new situation.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Right… so tell me how to get the broken stud out.

“What your actual solution is is unimportant as long as it has Quality. Thoughts about the screw as combined rigidness and adhesiveness and about its special helical interlock might lead naturally to solutions of impaction and use of solvents. That is one kind of Quality track. Another track may be to go to the library and look through a catalog of mechanic’s tools, in which you might come across a screw extractor that would do the job. Or to call a friend who knows something about mechanical work. Or just to drill the screw out, or just burn it out with a torch. Or you might just, as a result of your meditative attention to the screw, come up with some new way of extracting it that has never been thought of before and that beats all the rest and is patentable and makes you a millionaire five years from now. There’s no predicting what’s on that Quality track. The solutions all are simple…after you have arrived at them. But they’re simple only when you know already what they are.”

Okay, so pretty much useless.

Why am I on about this?

Well, guess who had to deal with a snapped-off bolt?

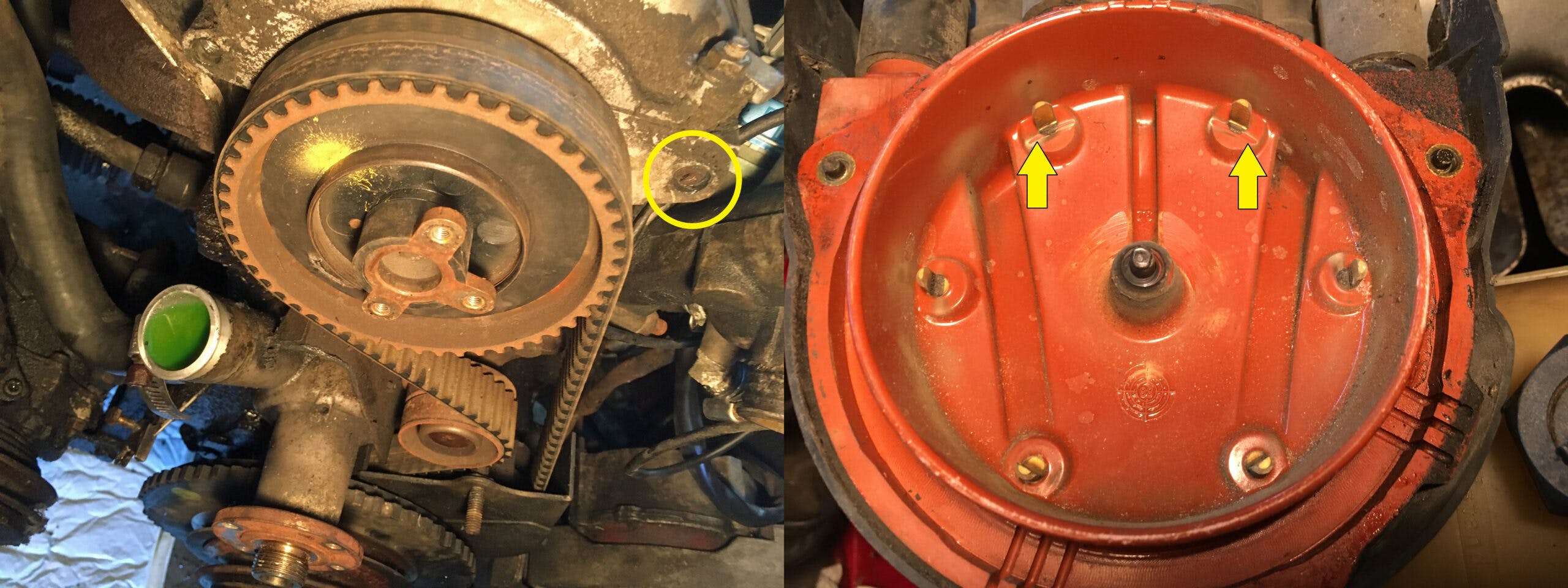

As the weather in Boston warmed, I returned to resurrecting the air conditioning in the FrankenThirty, my salvage-titled 1988 BMW E30 325is. I pulled the rusty original serpentine-flow condenser out of the nose and was about to swap it for a new parallel-flow condenser when I remembered something: I’d encountered a snapped-off bolt last August when I bought the car and was resurrecting it. It was one of the bolts holding the upper timing cover. Because this car has a timing belt and not a chain, the timing cover is really just a dust cover, so the missing bolt wasn’t part of an oil seal or anything, but it not being there had an unusual consequence. The distributor cap (well, there’s no actual distributor because the spark advance is computer-controlled, but there’s still a cap and a rotor) is bolted to the upper timing cover, so the fact that the cover was unsecured at one corner created a misalignment that was allowing the spinning rotor to wear a groove in the cap.

Now, if a bolt is stuck but hasn’t yet snapped off, I detail a number of techniques for removing it in my book (all of them are basically heat, grip, and the right amount of leverage so you don’t snap it). But if the bolt head has snapped off and left nothing to grab onto with Vise Grips or an external-gripping stud extractor, I’m only aware of two real choices: Drill out the bolt, or weld a nut to it.

Let me set something straight right now. There’s a widely-held misconception that the purpose of drilling out a bolt is so you can put an EZ-Out in it, turn it counter-clockwise, and back the bolt out. If you want to do that, knock yourself out, but know that the experience of yours truly as well as thousands who have gone before you is that if the bolt’s threads are so seized in the hole that the head of the bolt snapped off, the odds of it suddenly saying “Oh crap this guy’s got an EZ-Out I’d better high-tail it out of this hole where I’ve been living since the Eisenhauer Administration” is vanishingly small. In fact, the odds are that what’ll happen is that the hardened-steel EZ-Out will snap off in the hole, in which case you are truly, magnificently, and completely boned. In general, the best thing you can do with EZ-Outs is to go to your toolbox right now, find them all, and throw them all away, thus removing the temptation that this time they’ll help you instead of pulling the football out from Charlie Brown.

(A few people in the cheap seats are grumbling that you can use left-handed bits to drill the hole, and maybe, if The Automotive Powers That be are smiling on you, the heat and the left-handedness of the drilling will loosen the bolt so that the EZ-Out will in fact back the bolt out. I’ve had it happen. Once. In nearly 50 years of wrenching. It’s not a bet I’d make in a situation where, if EZ-Out snaps, you’re screwed.)

So, you’re not going to use an EZ-Out, why drill out a bolt? Because, most of the time, what you’re trying to do is remove as much of the bolt as possible. If you drill exactly in the center of the bolt and use progressively larger and larger bits, you can then re-thread the hole by using a tap. Or sometimes, if you’re lucky, once you’ve removed enough material, you can start to peel off the remnants of the old bolt using a pick, sort of like peeling an orange from the inside. Or if the bolt isn’t really supporting a big load, you can cheat and tap a smaller hole for a smaller bolt (shhhhh, don’t tell anyone I told you). But whichever of these options you use, it’s slow-going work, and it’s trickier to do on a blind hole (one where the drill bit never emerges from the back).

So you can imagine the attraction of the weld-a-nut-to-it method. There are dozens of videos on YouTube showing this being done, sometimes in a matter of seconds. If the surrounding metal is steel, you put a washer around the threads so the weld will stick only to the bolt (whereas if the bolt is snapped off in aluminum, it doesn’t really matter, as the MIG wire won’t stick to aluminum). If the bolt is snapped off below the surface of the threads, you need to build up a pool of melted wire on top of it. Then you weld the nut to the mound and/or washer. The beauty of the technique is that, in addition to creating something you can twist, the act of welding to the broken bolt—of putting a crap-ton of amperage through it—directly heats up the bolt, which, just like applying a torch or an induction heater, can help to break the bond of corrosion in the threads. At least in theory. (As they say in physics, in theory, theory and practice are the same, but in practice, they’re not.)

Now, I do own a welder, a Millermatic 141 that I bought about ten years ago when I had dreams of teaching myself how to weld and doing my own bodywork. That never happened, but I have used it a couple of times to do the weld-the-nut-on trick. Both times were on snapped-off exhaust studs on heads that I’d already removed, so I had them on a milk crate on the garage floor, and the surface I was attacking was horizontal. This time, I was about to try removing the FrankenThirty’s snapped bolt with the engine in situ.

So, back to the present. The FrankenThirty was sitting in the driveway with the grilles, condenser, and radiator out, and as I looked through the nose at the front of the engine, I remembered the snapped-off bolt, and thought “It’ll never be easier to deal with than right now, and if you don’t, you’re going to worry about that distributor cap cocking just enough to cause the car to die on the George Washington bridge. Do it now.”

I rolled the welder out into the driveway, and… long story short, I couldn’t get the technique to work.

It seemed to start off well, though. I cleaned the broken surface of the bolt with a Dremel tool. I shielded the car’s rubber timing belt first with aluminum foil, later with a cut-up disposable roasting pan. I built up a nice mound on top of the snapped-off bolt, though it drooped due to gravity.

But whenever I tried welding a nut onto the mound, I got very little adhesion. I tried holding the nut in place with needle-nose Vise Grips. I tried pounding it on with a hammer so I had a clear shot at it with the welder. I varied the amperage and the wire speed. I read in GarageJournal that you may need to try this multiple times before the nut sticks. Of the 17 (yes, 17) nuts I tried, only three of them stuck enough to even begin to put any torque on the bolt.

In frustration, I called a good friend of mine, a professional wrench who welds in his sleep. I explained what I was doing and what kept going wrong. His reply was the last thing I ever expected him to say:

“Yeah, I’ve tried the weld-a-nut-on trick. I’ve tried it with and without the washer. I’ve only ever gotten it to work once. I always wind up falling back to drilling the damn thing out. The only thing I can recommend is that new nuts almost always come with a coating. You might try drilling out the threads and belt-sanding the faces.”

So I did. No difference. I’m not sure what the problem was. Maybe lack of good electrical contact between the nut and the head for everything to heat up together and the melted welding wire to adhere to both. I gave one last try by abandoning the nut and trying to build up a weld mound (as that seemed to work fine) that I could grab onto with needle-nosed Vise Grips. I did succeed in getting enough of a grip to convince myself that, no, the broken bolt wasn’t simply going to unscrew if I could get something on it to twist it. It reached the point that I worried about risking damage to the head, as well as to the rubber timing belt I was trying to shield with a cut-up roasting pan.

So my future clearly involved a drill. I found that my left and right-handed bits were too dull to be functional. I read up on and watched a few videos on the best bits to use to drill out bolts, and one fellow swore by Bosch glass and tile bits. I ordered a set, ground off the welded mound I’d created, center-punched the face of the bolt as best I could (which wasn’t very accurate at all), and used the smallest (1/8”) bit. I wouldn’t say it cut through it like butter, but there was progress. I then moved up to the 3/16” bit. In about 15 minutes, I’d drilled myself a decent hole.

The original bolt was a metric M8 with a 13mm head, but it originally held not only the timing cover but also an engine hoist bracket. Since all I needed to do was secure the corner of the timing cover so the distributor cap didn’t wander around, I thought I’d use a smaller M6 bolt with a 10mm head. To my surprise, though, I couldn’t find my M6 tap anywhere. I did, however, find a 10-24 tap, and by coincidence, the hole I’d already drilled seemed to be the right size to receive it. A quick trip to my local Ace Hardware store revealed another surprise—they didn’t have 10-24 cap head bolts that short. They did, however, have an Allen-head bolt just the right length. A washer, a lock washer, a bit of blue Loctite, and done.

So. If you snap off a bolt and leave nothing to grab onto, if you have a friend who has a welder and swore he’s done this a dozen times, take him or her up on the offer. Maybe they actually know “how to do it.”

But don’t look in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. The only Zen about stuck bolts is being calm enough not to commit hara-kiri with an EZ-Out.

***

Rob’s latest book, The Best Of The Hack Mechanic™: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and assorted automotive mayhem, is available on Amazon here. His other seven books are available here on Amazon, or you can order personally inscribed copies from Rob’s website, www.robsiegel.com.

I spent 17 years spinning wrenches professionally in the heavy diesel arena. I knew about 3 guys that could always get the welder to work for them.

I’ve welded about a dozen times total in my life, so the drill and/or a flexshaft grinder have been my go-to.

With patience, I’ve fully removed the bolt and saved the threads about 9/10 times on average.

It never sucks any less, though.

If you can grab a hold of it in any capacity, heat the metal surrounding it as hot as you’re comfortably willing to, shock it with some penetrating oil, and give it a twist.

My most successful extraction method has been that approach, by far.

Signed, a former diesel tech, playing in the salt belt of Southern Ontario, Canada.

Errrr….that would be Eisenhower…

Whoops, thanks, not sure how I did that.

German car, German Eisenhower

Here is the best thing I ever figured out: This only works if you could get vice grips or something on it, vice grips are garbage for this, instead, use a pipe wrench. The beauty of the pipe wrench, is that it doesn’t slip like vice grips, instead the harder you torque, the harder it grabs.

Best thing i ever figured out.

One tip on the welding, make absolutely sure the bolt is cleaned and the nut is cleaned. Use laquer thinner and do not touch them after you clean it up. you should also preheat the broken stud/bolt to release any oil around it or on the threads. A real good quality heat gun will work, no need for fire. Cleaning is key and real out about 6 inches of wire and cut it, especially if your welder sits a lot. I also use ez outs, drill till there is nothing left of the bolt. It will come out. Most people drill a tiny hole, smash in the ez out then break it. You need to drill till almost its full diameter, insert and ez out and it will come out no problem. Welding is the best alternative.

The first mistake anyone can make is to reference Pirsig for help on anything! The second is to read Baconhat’s post above and believe the “no problem” statement. The third is to think that there really IS a foolproof way to remove a broken bolt. Go back up and re-read Colton’s comment – especially the part where he says that even if you’re successful, “It never sucks any less”. That’s a Fact of Life right there, folks – put it on a poster!

I recall when I first ran across “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Repair” and expected it to be interesting. Boy, was I disappointed. I’m sure it appeals to someone, but for gearheads, the title is misleading. Too much “Zen” and “Art” and not enough repair!

I take back what I said about not consulting Pirsig for ‘anything’…he’s great for putting one to sleep. I can’t tell you how many times I woke up in the morning with that book on my chest while trying to wade through all the existential stuff just to read a few pages of motorcycle trip stuff! 😉

There are many shop manuals that follow the Monty Python method. Let’s say you need to remove a center console to get to something, but when you examine the console, it’s just not clear how to do it without damaging it. You go to your trusty shop manual to see the steps to remove the console, but the instructions in the manual read “remove center console”. Argghhh!

Most of the nuts you find in your spare hardware stash are zinc plated and will not weld worth a darn. If you can’t find unplated nuts, perhaps burning the plating off with a torch and wire brushing to bare metal will allow a good weld.

Between stuck, broken, and stripped fasteners; brittle electrical connectors; and unreachable places, I stopped finding any enjoyment at all in working on cars. Not even a sense of accomplishment, just anger that I had to do something so completely miserable. And that really sucks, because having the work done has become so expensive. So now when one of my cars needs something, I have to choose between the unpleasant options of doing the work myself and blowing a hole in my bank account. Either way, I fall out of love with cars a little more each time it happens.

I am so sorry. I regard it as part of the rhythm of things. I’m not saying I do the “enjoy the s-u-c-k” thing that military people quote, but when I’m through to the other side, I DO enjoy the sense of triumph.

Thanks. I’d like to get that feeling of triumph back, really. And it would be nice to save the money by doing more work myself. I think a big part of my problem is that I just don’t do these things enough to get good at them. If time, space, and resources were no problem, the idea of getting a couple of junkers to practice on would be quite appealing. But if I had that kind of money, I guess I’d also have the money to spend on letting the pros do all the work on my cars.

1) get a garage fridge

2) stock it with beer

3) invite some car nut over

4) you’ll gain some of the “fun” back and probably save some dough

I feel the same way these days about working on cars. Although I do greatly enjoy working on bicycles! Everything is simpler and more straight forward on a bike. The tools are cheaper, the instructions from Park Tool Company are usually very detailed (with good pictures!), and as long as you buy name brand parts from reputable shops then the quality is quite good these days. Also a LOT cheaper (unless you want it to be a LOT more expensive).

I live in the north, I’ve wrenched for over 30 years. I have welded on nuts and removed hundreds of broken bolts. It’s not magic, or even complicated.

“In fact, the odds are that what’ll happen is that the hardened-steel EZ-Out will snap off in the hole, in which case you are truly, magnificently, and completely boned.” Nailed it 100%. Burned through two carbide dremel bits getting it out….

That quote oughta be on a t-shirt.

Rob, at what time during the exercise of trying SEVENTEEN different nuts did you firmly conclude this may not work? Just wondering as you know there are some people out there that think that if they keep doing the same thing over and over that eventually the outcome will be different. memo to file, the outcome never changes. 🙂 🙂

Some people try a bolt extraction technique, get good results, and laud it as the end-all-be-all of bolt extraction techniques. I have tried them all and the one I have been least successful with is the weld the nut technique. I’ve used your technique of tapping a smaller hole inside the broken bolt more than once.

I have a friend who is a lifelong welder. He claims he can get almost anything out…and I’ve certainly seen him do it. He is not a philosopher and has probably never read Pirsig, but he exudes quality in everything he does.

Our most recent challenge was a broken 5/16 bolt in the end of a Polaris snowmobile front drive shaft. I was thinking pull the track, pull the drive shaft – it’s a big job – and then tackle the front shaft. He said he could do it in situ. He did, even though the bolt was broken off 1/4 inch into the shaft.

I have to disagree with Peter above on one thing; it sure looked and felt like magic.

It appears that you destroyed the dowel pin aligning the timing cover casting. Now there is a single dowel remaining on the left side of the cam gear, meaning your fasteners in clearance holes are locating the part – which they will not do well.

Keeping the dowel without a fastener would have made more sense if locating the part were your primary concern

When I do the “weld a nut” technique, I always use a washer, as thick as I can find, fender washers if possible. I weld the washer to the broken bolt then weld a large nut to the washer.

So let’s say I’m trying to extract an m6: I go with a 1/4” fender washer to the stud, and then weld an m10, maybe even m12 if I have the room, to that.

You then need to make sure it cools *just enough* before trying to loosen it; near molten metal is obviously too soft and will just twist right off.

Can’t say it works every single time, but I’ve gotten pretty good at it.

I was helping my friend replace the shifter cable in his inboard-outboard boat. The videos showed all of the steps. It was going to be a snap. Until we got to the point where we were to “unscrew the old cable housing and install the new one’. The cable housing end was a brass pipe thread going into an aluminum housing. After rounding off the fitting with the ‘special $25 socket they sold us’ we resorted to cutting the cable off, then snapping the fitting off with a pipe wrench (not our goal). Ended up running to Harbor Freight for a pipe tap and drill to remake the threads. Rest of the install went off without a hitch – 3 hours later!