Media | Articles

Tracing the colorful, surprising history of Canadian Tire Motorsport Park

I was on a podcast recently and part of the conversation centred around the notion of using familiar corners as points of reference when learning a new track. I’m one of thousands who use the technique, but my racing education was different than that of most drivers. My home track is Canadian Tire Motorsport Park (CTMP), and I learned much of my craft there.

Sure, the Nürburgring Nordschleife may be more complex, and Road America and Road Atlanta are nearly as fast, but CTMP’s ten-corner Mosport Grand Prix circuit presents a unique set of challenges. Many Canadian racing drivers who proved successful on tracks all over the world started here, 20 kilometres north of Bowmanville, Ontario. Even when I was young, the adage ran: “If you can go fast at Mosport, you can go fast anywhere.”

Conceived in 1958 by the British Empire Motor Club, the organization established a company called Mosport Limited to construct a road racing circuit an hour or so east of Toronto.

As the story goes, Sir Stirling Moss was shown the circuit plans, and he suggested changing the proposed, single-radius corner five into a corner combination. Under his guidance, 5A became a longer-radius, uphill corner that immediately blended into 5B—a tighter, flat, 90-degree corner that led onto the long back straight. This corner combination bears Sir Stirling’s name: Moss Corner.

The name Mosport, a portmanteau of “motor” and “sport,” is pronounced MO-sport, not MOSS-port. The latter is still used by many racing fans today and, given Sir Stirling’s involvement, one can understand the ongoing confusion.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The circuit still follows the original layout. Fast, sweeping corners rise and fall with the hills quicker than a rollercoaster. The long back straight—the Andretti Straight, as it’s now known—isn’t even a straight. As the elevation rises from Moss Corner, you turn a little left and a little right as your speed climbs, until you brake and settle into the final corners before the front straight.

Sanctioned competition began in 1961 and that summer, the Player’s 200 attracted the top names in motor racing. Records show that Moss won the event, followed by Jo Bonnier and Olivier Gendebien. Since that event, all of the racing greats have competed or have won races at Mosport.

Mosport hosted its first Formula 1 Grand Prix in 1967. Jack Brabham, piloting a Brabham, snagged first, with teammate Denny Hulme finishing second and Dan Gurney taking third. With the exception of 1968 and 1970, when the event moved to Quebec’s Circuit Mont-Treblant, the Canadian Grand Prix stayed at Mosport through 1977. In 1978, the race moved to its current home of Montreal at the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve.

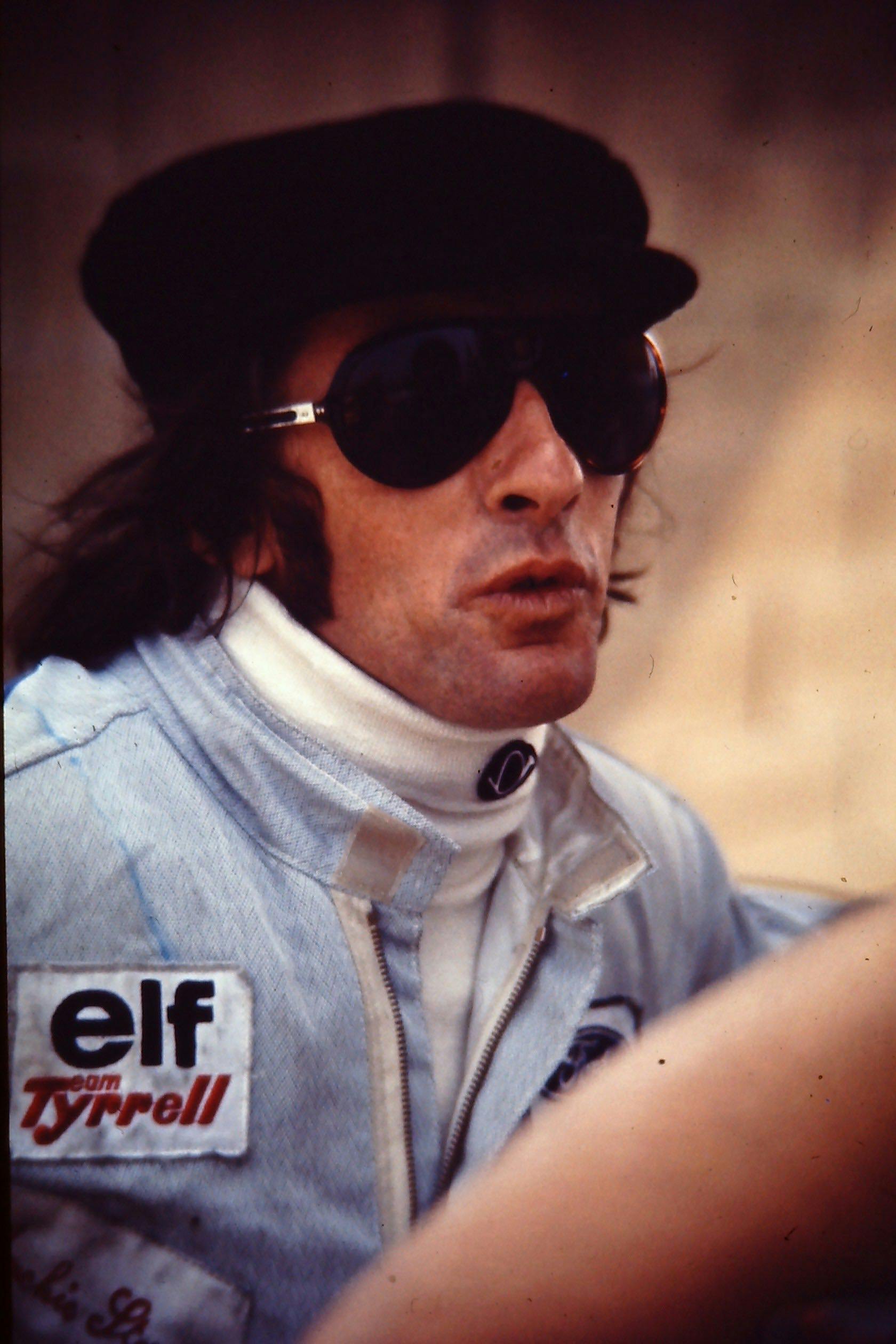

Mosport has hosted IndyCar (then USAC), Can-Am, TransAm, American Le Mans, IMSA, and even NASCAR Truck championship events. The list of entrants over the decades reads like a who’s who of motorsport: Clark, Stewart, Andretti, Fittipaldi, Foyt, McLaren, Lauda, and Villeneuve.

Since the facility is located many kilometres from the nearest town, Mosport’s the perfect venue for non-racing events, too. Not long ago, I read a story by modern music historian Alan Cross about the Woodstock-style music festival held at Mosport in 1970. The Strawberry Fields Festival was held just a couple of years after the Summer of Love, so concert-goers were treated to a weekend’s worth of sex, drugs, and rock and roll. (Cross is a driving enthusiast and happens to be one of my more notable performance driving school students.)

Incidentally, Mosport’s president and general manager, Myles Brandt, was thirteen years old when he started working at the circuit in the summer of 1970, cleaning up after the Strawberry Fields Festival. Through the years, Brandt has worked in all parts of the operation, from concessions to sweeping the track to cutting the grass. He’s done it all.

At the time, Mosport was operated by Harvey Hudes, a legend in Canadian motorsport. Brandt recalls: “Harvey was like a second father to me. He was hard-nosed, but he was very fair. He ran it as a business, but he also was an enthusiast about it. He liked racing and wanted racing to succeed. He did a lot of things that people probably don’t remember, but he did a lot to keep the Can-Am series going and trying to promote open-wheel racing in our country.”

Hudes was the driving force behind Mosport from 1966 through to his death in 1996. If running a profitable racing circuit were easy, everyone would do it—and in Hudes’ time, he had to watch every penny.

Naturally, all of the great tales about Mosport orbit motor racing legends, and Canadian journalist Norris McDonald told me a funny story about Mosport in Hudes’ era.

“In 1976,” McDonald says, “There was an invitation to the media [personnel] who was there for the grand prix to take a tour of the track with James Hunt doing the hosting. They had forty or forty-five reporters from various parts of Canada and a number of the international media.

“We got on the bus and I noticed Bernie Kamin (Hudes’ partner in Mosport) was sitting right in the front row and Hunt didn’t know who Bernie was. The bus pulls out of the pits and Hunt is telling the usual story about the fact that it’s a really challenging track.”

“Hunt stops and says: ‘I gotta say something and if I’m treading on someone’s toes, so be it. These guys are the cheapest guys to ever have a grand prix in the history of grand prix promoters. They won’t even buy a gallon of paint and make this place look like it’s a grand prix! How much would it cost to buy thirty or forty for all of the drivers’ different nationalities?’ And he talked about that for a good half-lap about that.

“I remember thinking, Bernie is going to go back and tell Harvey and maybe they’ll spruce the place up. It never happened,” McDonald says.

After Hudes’ passing, the circuit changed hands. It was run for a couple of years by International Motor Sports Group—which was owned by Bill Gates’ banker, Andy Evans—and renamed Mosport International Raceway.

Don Panoz bought the facility outright in 1998 and made the first meaningful improvements in decades, though he retained the racing circuit’s original layout. The updates allowed Panoz’s American Le Mans Series to make annual appearances at the track from 1999 through 2013 and paved the way for future events like the annual Mobil 1 Sportscar Grand Prix for IMSA prototype GT entries and the Chevrolet Silverado 250 for NASCAR trucks.

In 2011, Canadian motor racing legend Ron Fellows and his partners Carlo Fidani and Alan Boughton bought Mosport from Panoz. A few months later, they entered into an agreement with Canadian Tire, and the facility is now known as Canadian Tire Motorsport Park.

I asked Fellows how they got the idea to buy the place. “I can tell you it was not my idea,” he says. “Carlo would probably deny it, but it was Carlo Fidani’s. We were at my school in Nevada back in 2010 and we were there with his two sons and Al Boughton. We were talking and Carlo said, ‘We should buy a track. Do you think Mosport would be for sale?’

“And I said, ‘Well, I don’t think it is, but I know who would call.’ And that’s how it started with a call to Don Panoz and Scott Atherton. Given Carlo’s business and understanding of what’s involved in a commercial property acquisition, we couldn’t have done it without him. We’d still be trying to figure it out.”

“It wasn’t something Don Panoz was looking to do,” Fellows says. “He liked us. He liked Carlo and they hit it off. He thought that it was likely a good idea that it gets back in the hands of Canadians. That was really how it started. On June 1, 2011, we took over.”

Though the new partners retained Brandt as general manager, major changes followed. Boughton exited the ownership group, leaving Fellows and Fidani at the helm. CTMP now includes the Mosport Grand Prix track, the Driver Development Track, a karting facility, and a modern event centre situated perfectly on the hill across the circuit from pit lane. One thing remains the same, however: the flat-out character of the Grand Prix circuit.

Fellows’ racing career is inextricably connected to CTMP’s history and has come full circle. “Importantly for me was the relationship I had with Harvey Hudes, one of the original owners. Harvey gave me some good advice in the early ’80s.” Fellows laughs, “He said, ‘Ron, forget about open-wheel cars—you don’t have enough family money, you’re too tall.’

“He said, ‘Go sports car racing. There’s Trans Am and IMSA. There’s manufacturers looking to hire drivers and if you’re any good, they’ll find you.’ That was very good advice,” Fellows recalls.

The rest is history. Fellows went on to earn the nickname ‘The Mayor Of Mosport.’ When I pressed McDonald on who should be credited with bestowing that nickname on Fellows, he said, “I don’t remember who coined it, but it might have been Myles!” Whether true or not, it’s a great story.

CTMP has been a magical place for me. I first visited as a spectator in 1988, and hiking around the four kilometre-long circuit was an eye-opening experience. After watching races on television and devouring photographs in the periodicals of the time, nothing prepared me for the size of the 450-acre facility nor the wild elevation changes at different parts of the circuit.

After a couple of racing schools and track days elsewhere, my first laps were in the passenger seat of Fellows’ Players Ltd./GM Motorsport Chevrolet Camaro. It was a wild ride. Mosport was the fastest circuit I’d ever experienced. Most corners were blind—and if you weren’t going uphill, you were descending rapidly. Even as a young twenty-something, these high-speed rollercoaster laps that Fellows gave me had me questioning my decision to become a racing driver.

I asked Fellows whether he attributes his success to honing his skills on CTMP’s Mosport Grand Prix circuit, and he began to answer before I could finish asking the question. “Yes, yes, and yes. And it’s not just me,” he says. “It’s a number of generations of Canadian drivers. I quickly found out that, when I went into the Trans Am series, that learning how to go fast and learning how to win—if you could do that at CTMP, you could go fast and win anywhere. All the lessons learned in managing elevation change, high-speed cornering, [and] we learned that predominantly at CTMP.”

“Emerson Fittipaldi told me exactly the same thing,” Fellows continues. “His son was racing at our kart track two years ago and I get a phone call and it says ‘Fittipaldi,’ and I said, ‘I’ll be answering this!’ He wanted to come and see the Grand Prix circuit. He hadn’t been here since last raced there in ’77.”

“We drove around in a Camaro ZL1 and he said the same thing: ‘If you can be fast here, you can be fast anywhere.’ He said even with all the safety upgrades, the character of it remained for him and he just thought it was so cool. He kept saying, ‘It’s a fantastic circuit! Fantastic circuit!’”

I asked Fellows what it’s like to be a custodian of this important part of motorsport history. “That’s exactly the right term. Carlo, Myles, Lynda [Fellows, Ron’s wife], and I talk about that a lot. We’re the next generation of ownership and that’s been our job right from the start: Take this iconic racetrack, create some further development, and leave it better than when we got it.”

2021 is the sixtieth anniversary of this historic circuit and the entire team at Canadian Tire Motorsport Park hopes to mark the occasion with a celebration worthy of the facility’s history. I hope to be there, too.