Media | Articles

Ontario’s Multimatic has set the pace for damper tech since the 2000s, and it’s far from done

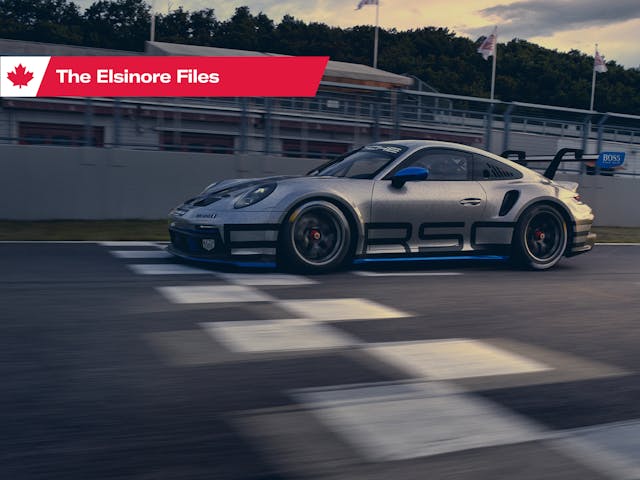

Late last year, Porsche Motorsport announced the launch of the seventh-generation 911 GT3 Cup race car intended for use in national and international championships around the globe. The 992-based racer is an all-new product for Porsche and is closely aligned to the 2022 911 GT3 road car. Both the road and race bodies roll off the same production line at Zuffenhausen.

I’ve been a fan of these production-based, spec-911 series for decades, but this announcement hit a little closer to home—literally. Canada’s Multimatic satisfied Porsche Motorsport’s rigorous supplier selection process and was chosen to provide the unique DSSV dampers for all 992 GT3 Cup cars.

Enthusiasts know Multimatic as a key partner in the 21st-century Ford GT and GT Mk II or from Aston Martin’s Valkyrie hypercar, but OEMs know the Ontario-based company as a Tier 1 supplier for components that range from door checks to tailgates. Chances are that you’ve driven a road car with components manufactured by Multimatic; if you’ve wheeled a Chevrolet Camaro Z/28 (or ZL1 1LE), Colorado ZR2, or even the Mercedes-AMG GT, you’ve driven on the company’s Dynamic Suspensions Spool Valve (DSSV) dampers.

To get some insight into Porsche’s process, I rang up Jeremy Sundt, customer experience specialist at Porsche Motorsport North America. Though his job title sounds innocuous, he’s the gentleman who receives all of the grief and complaints if any of Porsche’s 911 GT3 Cup cars don’t perform to teams’ expectations.

Having previously worked with noted racing supplier Cosworth, Sundt knows firsthand the strict process Porsche uses to select new suppliers for their race cars—from the other side of the table—and it’s not an easy task. With GT3 Cup cars, Porsche’s focus is on the quality of the product and parity from one car to the next. Given the ongoing success of GT3 Cup championships, I’d say they’ve been succeeding for quite a while.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“Our open competition cars, like our 911 GT3 R and RSR, are developed by performance engineers who want to win races. We want to win Le Mans, we want to win Spa,” Sundt said. “With one-make racing, that’s not the goal. The goal is to make the same car over and over again, and we also want to make a car that, in my opinion, if someone wants to get in there [and change things], they’ll make it worse.”

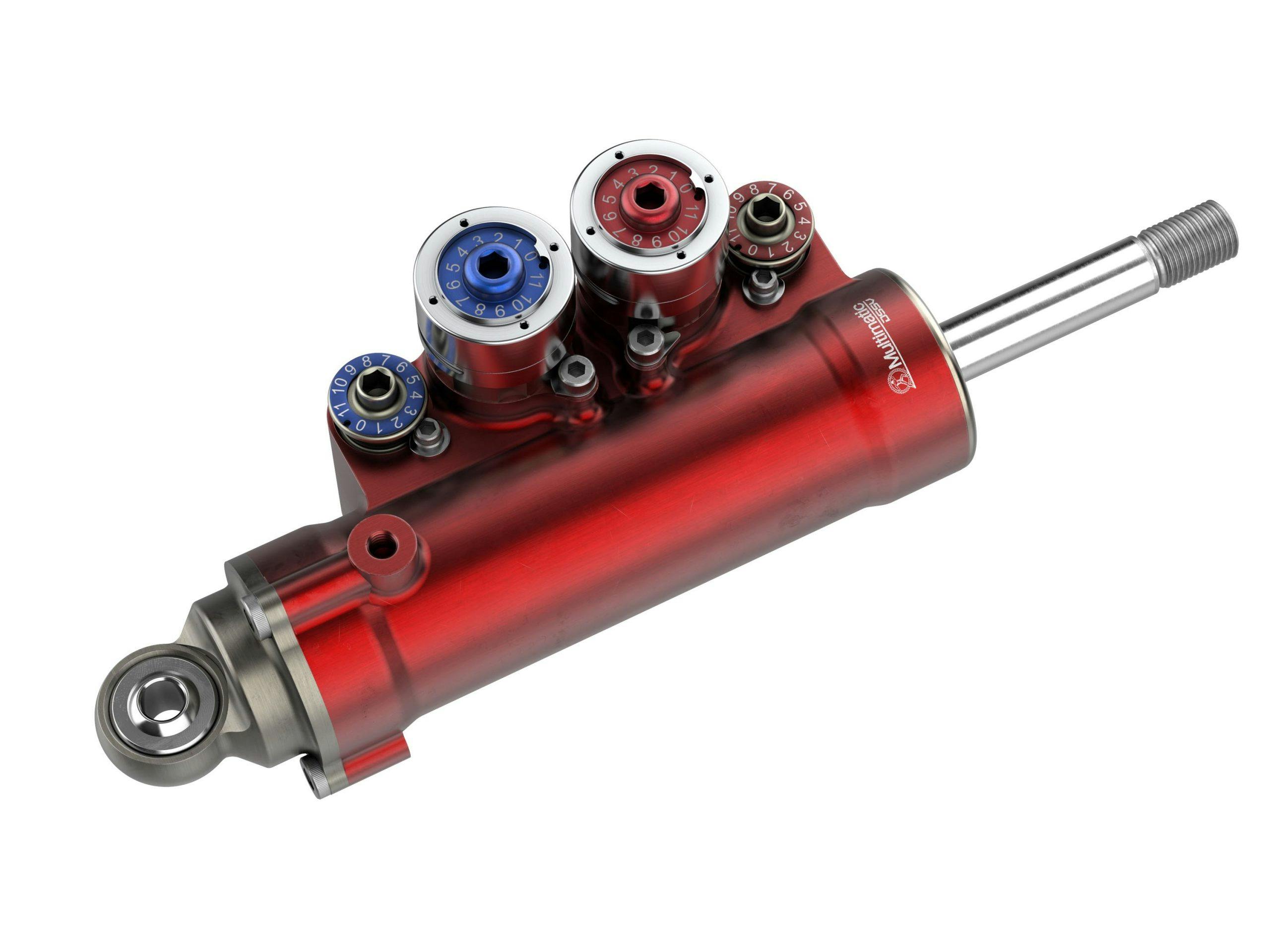

In motorsport, damper tech has always been a bit of a black art and, especially in spec series, these components are often the difference between winning and losing. Prior to this year’s Porsche Carrera Cup North America Presented by the Cayman Islands championship, top teams would have a specialized focus on dampers within their racing operations.

“Teams would have a truck full of dampers and go to the shock dyno with the dampers and master them all up to find the ones that are within three or four percent of each other,” Sundt said. “They’d all perform differently when they’re hot, when they’re cold, when they’re new. If you have that, then you have a series where the best teams are going to have thousands of dampers. The letter of the law says they can’t rebuild them, but they can get them rebuilt by the manufacturer—then they put the dampers back on the shock dyno, get their [force-velocity] curves, and find which dampers are best for individual circuits.”

It’s entirely possible, then, that a team competing in a one-make championship has an entire program dedicated to testing a component that, technically, it isn’t allowed to modify. What makes a good damper, according to Sundt? One that performs the same on day one as it does on day four, on the first hour of a race and on the twentieth. In this strange dance, the burden of optimizing the damper weighs even heavier on the original manufacturer.

“Imagine you’re a damper manufacturer and Porsche comes to you and says we need a damper to last for X hours on any track, at any temperature, and it has to produce the same damper curve at all times,” Sundt says. “Think about that.”

As it turns out, the DSSV damper is specified in the GT3 Cup car service manual as a 90-hour part, which is over three times the amount of track time drivers have available to them in this year’s entire championship—even including official practice and qualifying.

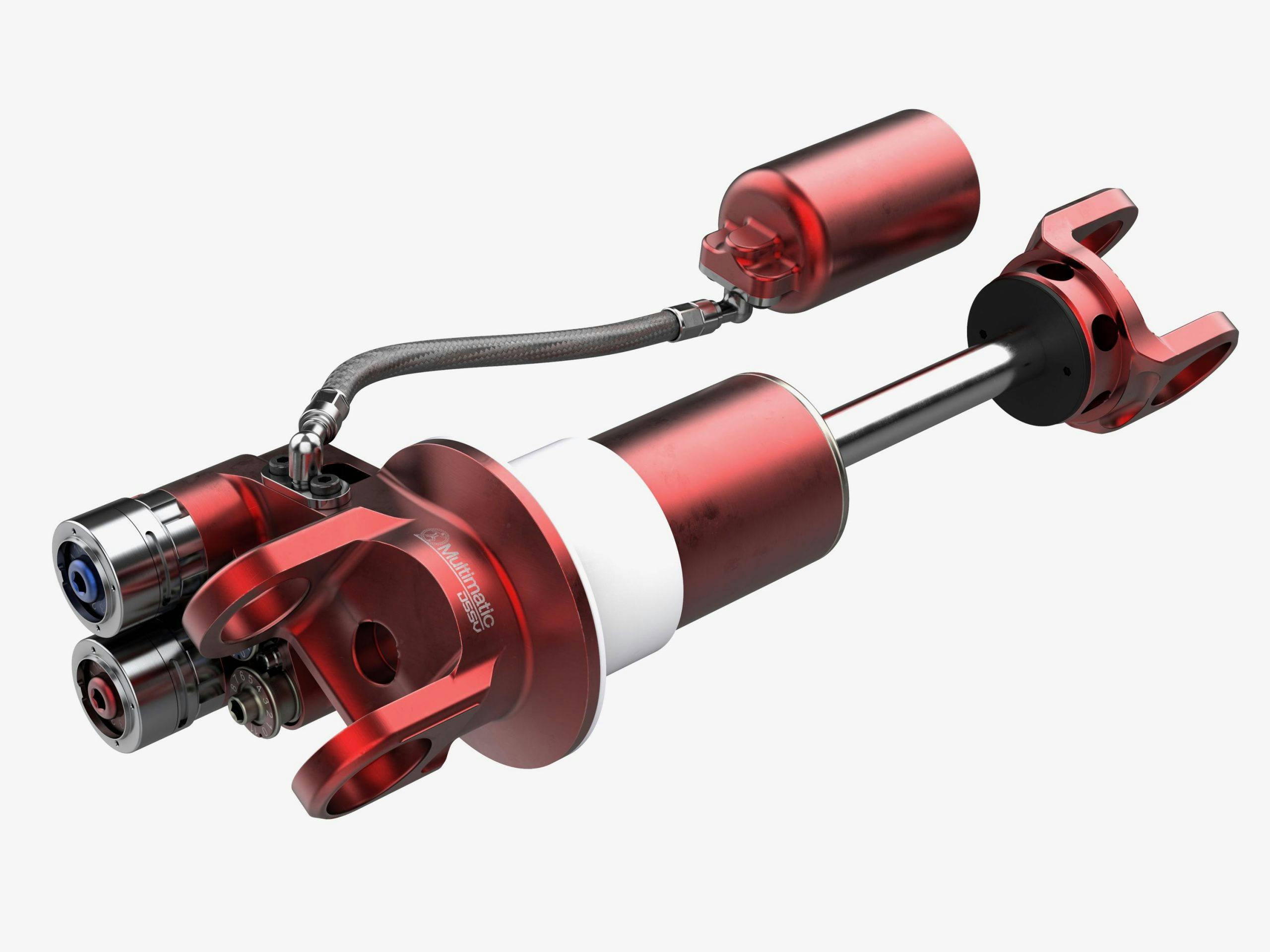

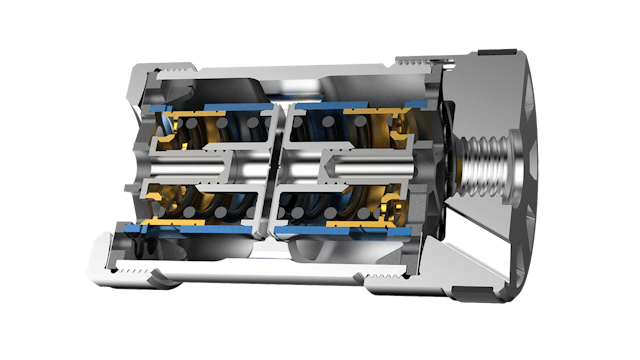

If there’s a company that can contemplate the development of a damper that can meet Porsche’s criteria, it’s certainly Multimatic. DSSV stands for Dynamic Suspensions Spool Valve, but the most important phrase to understand is spool valve. The Ontario-based company pioneered and patented spool valve technology for use in automotive dampers.

When I was introduced to the DSSV shocks in the 2014 Chevrolet Camaro Z/28, I knew nothing of spool valves and I was quickly educated by Larry Holt, the mastermind behind Multimatic’s advanced technologies and motorsport engineering. Mechanical engineers will recognize the nature of these valves because they’re used in aerospace or construction equipment for precision motion control of hydraulic systems.

The most common type of shock design today—whether tuned for road, race, and even off-road driving—uses stacks of shims (imagine flexible washers) to control fluid flow from one chamber to another within the shock body.

While shim-stack shocks have no doubt proven their worth, once you understand how spool valves work, you can appreciate that the more exotic setup is quite an ingenious solution. Spool valves allow dampers to retain that precise force-velocity curve across a range of environmental and driving conditions. While other shocks can vary as much as 10 or even 15 percent from one shock assembly to another, the precisely shaped orifices in Multimatic’s spool valve dampers are race- and road-proven with repeatable performance from damper to damper. They’re also much more resistant to heat build-up than other shock designs.

Spool valve dampers are certainly elegant, but they’re far from cheap. Perhaps that’s the reason they’re commonly found in motor racing, where the will to win is only tempered by a racing team’s budget—and it was in motorsport where Multimatic’s spool-valve dampers got their start. The company has been in the business of suspension components since its inception in 1984, but in 1999, it was struggling to build a damper with a precise force-velocity curve using existing technology.

Michael Guttilla, the company’s vice president of engineering, told me: “You can do it empirically by doing lots and lots of trials, but not in the predictive way. If I had a specific force-velocity curve I was looking for, there wasn’t a way to give me a singular set of hardware that some equation will tell me, from fluid dynamic principles, will give me that curve accurately and repeatedly.

“So, we said, the only way we know how to do that is actually what the rest of the world does when it’s trying to do precision flow control of a hydraulic system: They use spool valves.” Spool valves are commonly used in the aeronautics industry to control ailerons, because they allow for extremely precise flow control in a hydraulic system. Gutilla saw an opportunity to leverage this valve technology’s highly tunable character for motorsports.

“The nice part about spool valves is that they’re also analytically determinant, because you’re controlling a variable orifice and the spool varies the shape of the orifice. There’s a relatively easy set of equations for calculating what kind of pressure drop you’re going to get as that orifice varies. So, we had the idea to put a small valve inside of a damper.”

The company’s Dynamic Suspensions division was already supplying top CART team Newman/Haas Racing with its shim stack dampers in 2001 and the following year, it broke new ground with the deployment of the spool valve shock. With only two chassis and three engines to choose from, a key component like a precise, predictable damper gave a team an extraordinary advantage.

By the end of the 2002 CART season, Newman/Haas Racing driver Cristiano da Matta won seven of 19 races, five more than his nearest competitor, and walked away with the driver’s championship by a wide margin. After Newman/Haas Racing’s four championships, the series mandated a switch to a single-spec damper to eliminate the spool valve damper’s advantage.

The rest, as they say, is history. In short order, race engineers in Formula 1 learned about Multimatic’s magic technology and by 2010, Red Bull Racing won its first of four championships using DSSV dampers. Naturally, a number of F1 teams use their dampers today, though few will discuss it publicly, which is not surprising given the secretive nature of the sport.

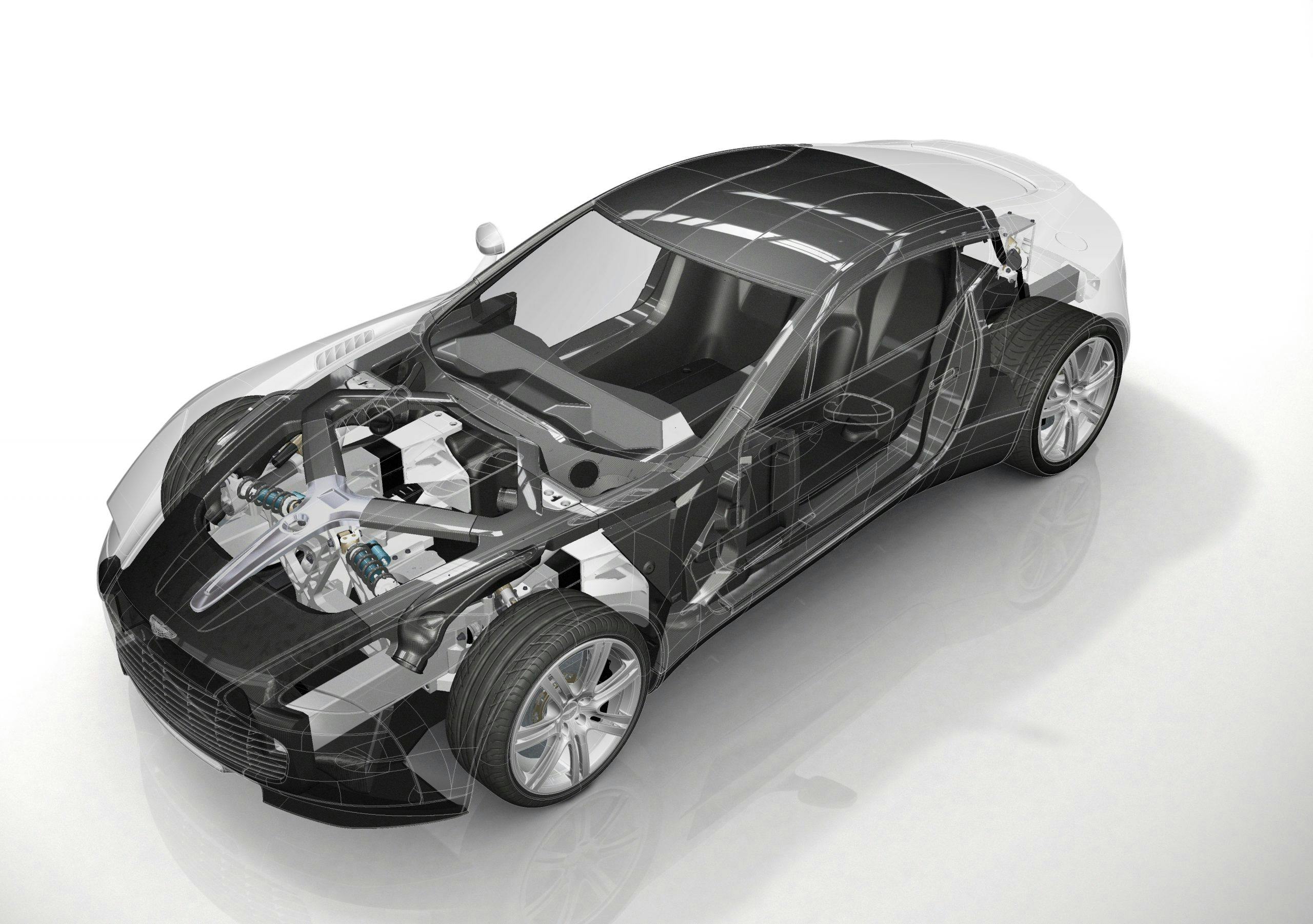

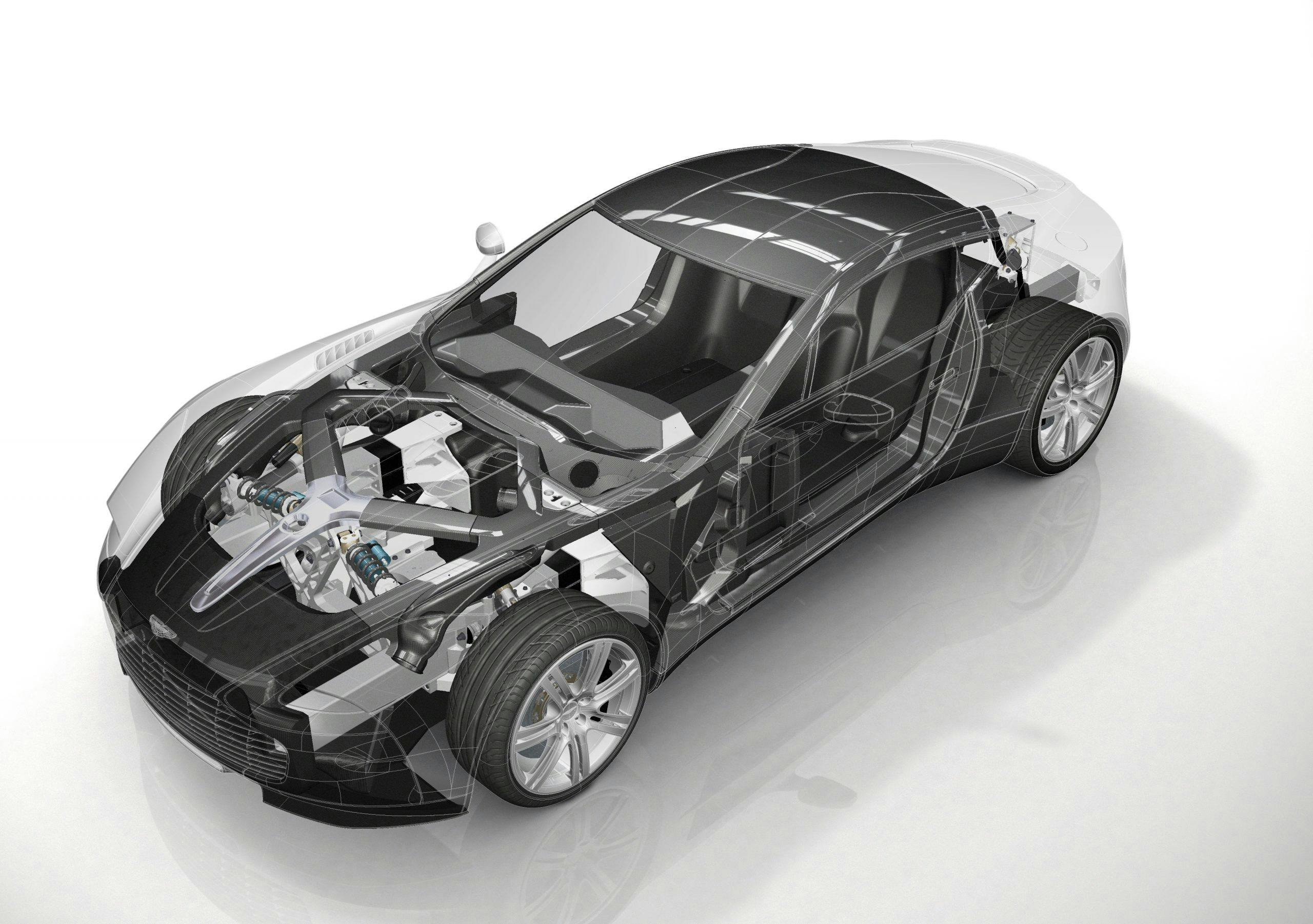

Racing technology has always trickled down to production cars, whether it’s disc brakes or composite materials, and road cars eventually benefit from engineering advancements. In addition to the Chevrolets and the AMG mentioned above, the Ford GT, Aston Martin One-77, and Ferrari SF90 Stradale Assetto Fiorano also ride on spool valve dampers, but these are all relatively low-volume applications. Multimatic has found a way to bring the benefits of spool valve tech to a wider range of vehicles by applying adaptive technology of its own.

Traditional adaptive dampers use magnetorheological (MR) fluid inside the shock body and the viscosity of the fluid varies depending on the intensity of the shock’s magnetic field, which varies based on inputs from the vehicle itself. From the automaker’s perspective, challenges with MR-based systems include long development times; for the car owner, the particles in the MR fluid can cause prematurely wear to the seals inside the shock. Plus, MR dampers don’t work well for many off-road vehicle applications, either.

Instead of changing shock-fluid viscosity, Multimatic’s new Adaptive Spool Valve (ASV) dampers begin with a conventional spool valve which resides within a ring with precisely cut apertures. That outer ring is rotated by an actuator that provides rapid changes to fluid flow through the damper and, in total, the system offers 16 unique force-velocity curves to optimize its performance for ride and handling or outright corner carving.

It’s certainly a more mechanical solution than an MR shock, but the ASV damper has real-time responsiveness, can be used in off-road vehicles, and promises to have a more natural feel for drivers, as well. It’s taken a few years, but this motorsport-derived technology is finally ready for prime time and I’m definitely looking forward to driving it.