Media | Articles

Overshadowed by its GM descendant, McLaughlin is the unsung hero of Canada’s automotive history

No tale of Canadian automotive history is complete without McLaughlin. The company, now known as General Motors of Canada, actually predates the automobile, and is so important to the company that, when my father retired from General Motors, the watch he received didn’t depict a Chevy or a Buick, but a McLaughlin.

A glance through the history of McLaughlin Motor Car Company reminds one that much of early automobile technology was derived from horse carriages, which is how Robert McLaughlin got his start in business. He founded the McLaughlin Carriage Company in Enniskillen, Ontario, in 1869. That part of the province was then very rural and now a stone’s throw from Canadian Tire Motorsport Park. McLaughlin soon moved the company to Oshawa, a larger city a few miles away.

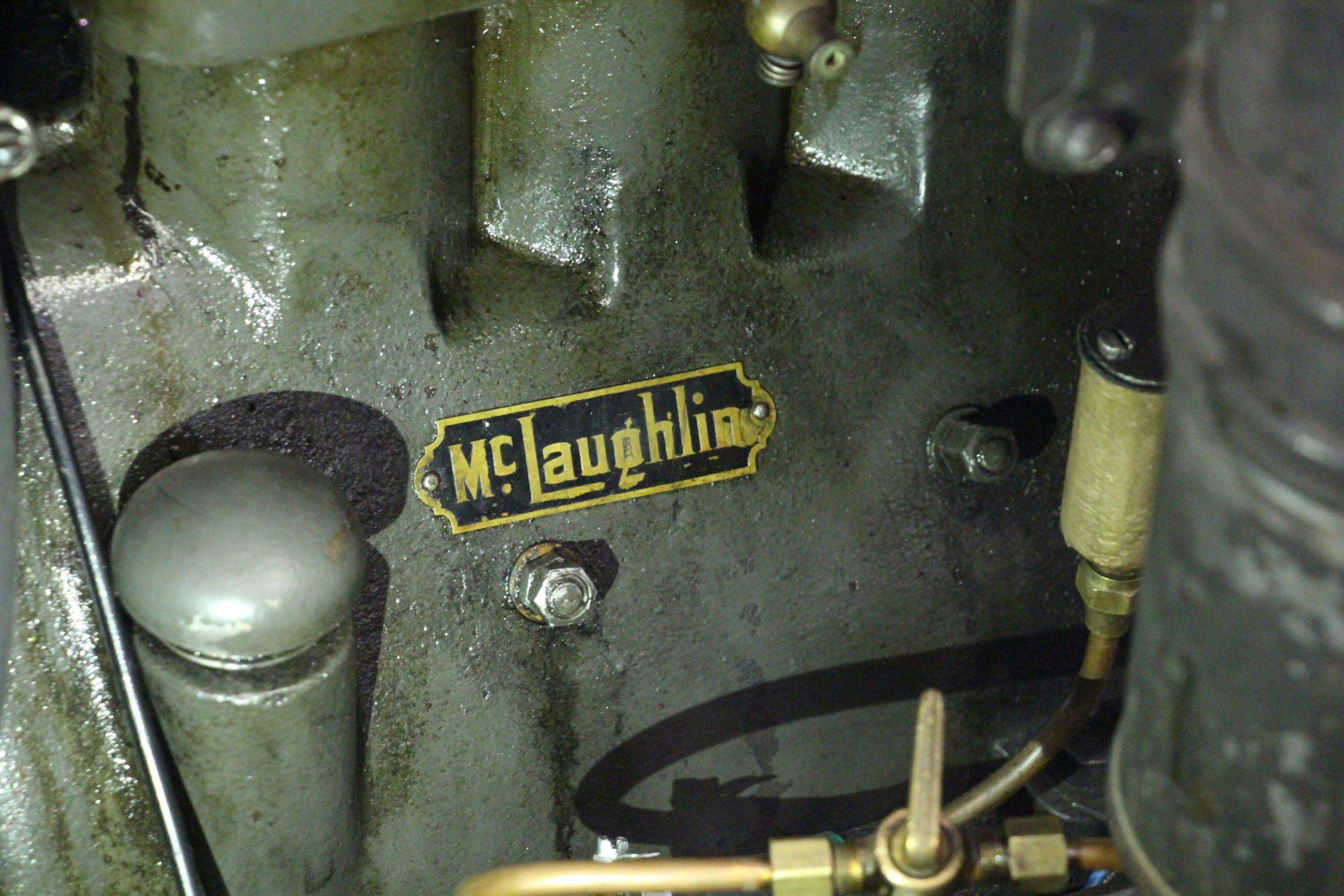

The carriage business proved successful, and Robert’s son Samuel, heir to the McLaughlin firm, began to turn his attention to automobiles. By 1907, the McLaughlin Motor Car Company was born. Like the earlier Fossmobile, McLaughlin automobiles used the prevalent technology; Sam arranged a partnership with Billy Durant for Buick drivetrains.

In those early days, the car business was rife with startups, failures, mergers, and acquisitions. By 1918, Detroit-based General Motors formed General Motors of Canada Limited and acquired the assets of McLaughlin Motor Car Company along with the long-term leadership of Sam McLaughlin. Today, though it’s been largely overshadowed by its GM descendent, McLaughlin’s legacy lives on in the lives of enthusiasts like Case Jansen.

A lifelong gearhead, Jansen acquired his 1919 McLaughlin HH63S convertible in 2020 from a gentleman who made him an offer Jansen couldn’t refuse. The previous owner kept the car in climate-controlled storage, but it hadn’t been driven in years. When he acquired the convertible, Jansen decided he would mechanically restore the vehicle so that he could share it with the world.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“I had considered doing a total restoration of everything,” Jansen tells me, “but [I talked to] different people, especially car restoration people that I’ve known for years, and they’re saying, ‘Why don’t you just drive it, because it’s eye candy for people.’

“You can put twenty thousand dollars, thirty thousand dollars into it to bring it up to that pristine showroom condition and it becomes a trophy rather than a car, because you’re not going to want to drive it. So I thought, I’m going to leave it alone. I’ll try and keep it clean. It’s got a few blemishes here and there, and so be it,” Jansen says.

After a career as a mechanic at a local nuclear power plant, Jansen has the mechanical aptitude and financial resources to undertake a project like this. Despite a complete lack of parts and support, things we’ve come to expect with more modern automobiles, he wasn’t intimidated by the project.

Though he has a few interesting muscle cars in his collection, Jansen wasn’t originally looking for a McLaughlin, but he was inspired by Samuel.

“I studied a bit of McLaughlin’s history because it enthused me,” Jansen says. “I’d been for a tour of his home in Oshawa and he had the nicest estate home in Canada when it was built. I thought that he was quite a guy and that’s from doing hard work and getting ahead in life. My goal has always been that if you want something, you’ve got to work for it, and McLaughlin always inspired me.”

His newly acquired convertible isn’t the only McLaughlin to figure in Jansen’s life. “I rode in one as a teenager in the backseat on a country dirt road, and I remember just sailing through the corners with a big fishtail. As a teenager, I was impressed like crazy, and I never forgot that car.”

When he first heard about the 1919 McLaughlin, Jansen wasn’t sure what to expect. At best, he anticipated finding an antique pile of parts and pieces; when he arrived at the storage facility and found the vehicle entirely serviceable, he jumped at the opportunity.

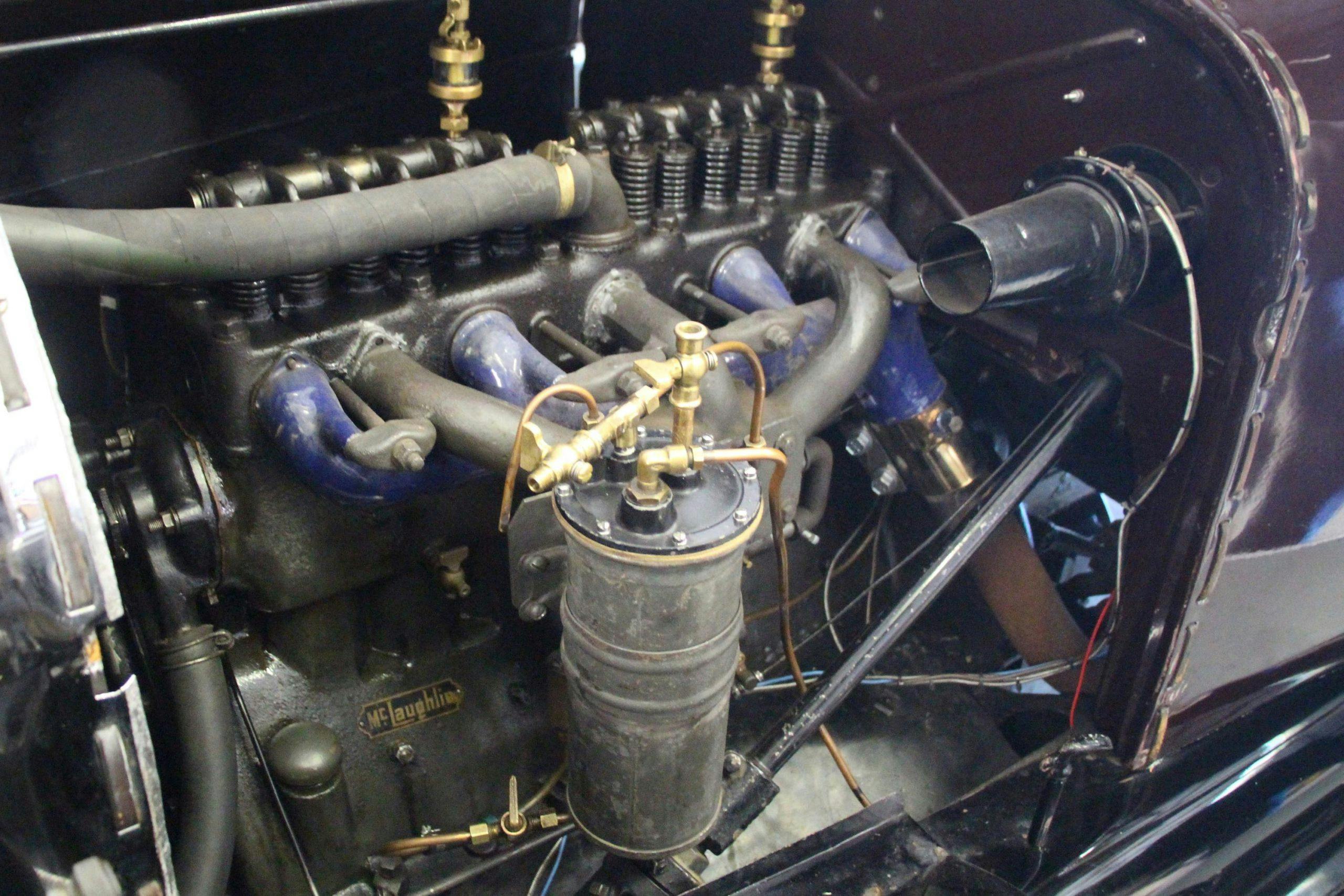

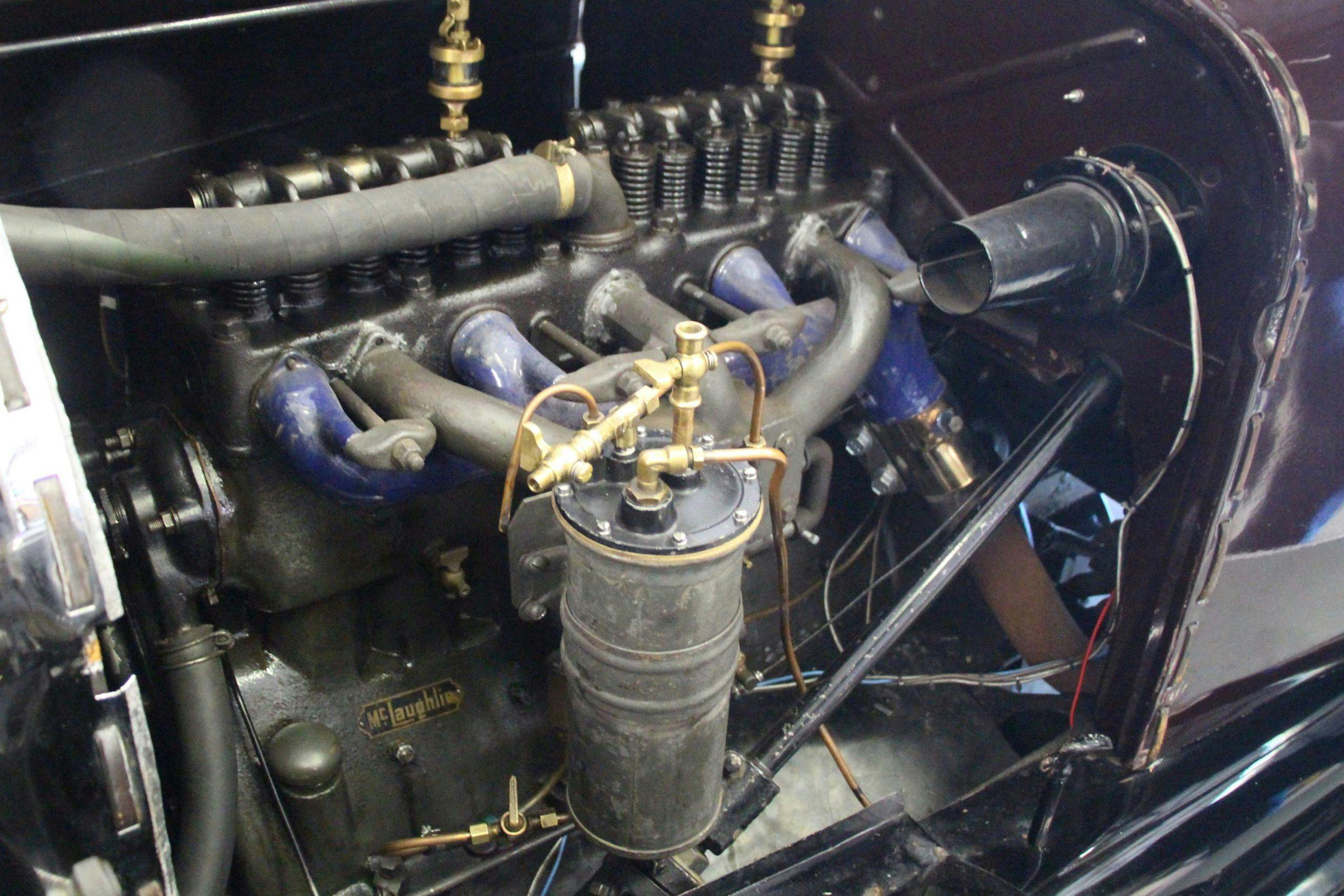

His McLaughlin is powered by a 36-hp, six-cylinder, open-valve engine that mates to a three-speed, non-synchromesh transmission which uses a cone clutch. Naturally, it’s rear-wheel-drive, with mechanical brakes on the rear axle. The throttle is a lever on the steering wheel, and the suspension purely spring-based, pulled straight from a contemporary horse carriage, and with no shocks to speak of. To improve passenger comfort, the seats are also sprung.

Jansen worked on his McLaughlin in his shop at his home in the rolling hills of Durham Region, fewer than 50 kilometres away from the factory in which it was manufactured. With a combination of Jansen’s mechanical know-how and the small but enthusiastic McLaughlin community, he was able to get his Canadian special back into running condition.

“Between myself and my friend Bruce, we have a couple of hundred hours into it. We’ve had the transmission out four times,” Jansen laughs. Most of the company’s documentation is lost to history and, while he can’t confirm it with complete confidence, Jansen suspects that this is the last McLaughlin of its kind.

When I visited, Jansen offered to take me for a ride and I couldn’t refuse a spin in a car made over a hundred years ago. Sounds emanate from all parts of the McLaughlin—the engine, the gearbox, the exhaust. It feels less like riding inside a car than like sitting atop a motorized horse carriage.

Although it requires a bit of a procedure to start, the McLaughlin fires up reliably and the entire experience harkens back to a time when roads were used primarily by horses and automobiles were an oddity. Today, we’ve got the benefit of a fully developed road system and it’s easy driving for a century-old automobile.

At the time, fuel systems used a vacuum-based delivery system, so cars of the 1910s wouldn’t climb hills very well. Maintenance tends to the labor-intensive: As Jansen learned, there are plenty of lubrication points; for example, every 100 miles he must add oil to lubricate the pushrods. There is an onboard oil can for those purposes, of course. Jansen has added one modern cheat to his McLaughlin: a fuel pump.

There is no heater to speak of, however. In colder weather, rear-seat passengers would prop their feet on a built-in footrest to keep their boots away from the cold floor and drape a heavy blanket over their knees to keep warm.

Jansen has his McLaughlin insured with Hagerty and says the process couldn’t have been easier, except that there isn’t exactly a market for these cars, so he had to work to determine a reasonable value for his century-old car.

As Jansen was driving me around the countryside in his car, we had a wide-ranging conversation. He speaks calmly and carefully, with the satisfaction of a man who has achieved a number of goals in life: Owning a McLaughlin is one of them. He clearly enjoys working on this car and relishes driving it.

“Even if I only drive it once or twice a year,” Jansen says, “it’s still fun.” I think he’ll be driving it much more often than that.