Media | Articles

Smithology: You need this book more than we needed a Cadillac Escalade EXT

John Phillips wrote columns. I know because I have read all of them. Or at least it feels that way. Ingesting the man’s writing is like watching Sunday-morning cartoons: You start, looking for a distraction from eating or sleeping or breathing, and an eyeblink later, it’s noon on a Tuesday, you are still in pajamas, and you think you know everything about My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic.

(Sam, in the future it’s sufficient to use the commonly understood acronym MLP:FIM — Ed.)

Or, in this case, the work of a man in your business. Phillips used to be executive editor of Car and Driver. Now he has a new book. I was tempted to review this work, and then I remembered that I am not a good reviewer of books. Too many stray thoughts, not enough critical overview, a general disdain for academic nitpickery. Also, in this case, I’m biased.

John Phillips is a legend, and that makes me happy.

Car magazines thrive on tall tale and rumor. The folks in their orbit who get remembered tend to thrive at the intersection. I have worked for three such titles—Automobile, Car and Driver, and Road & Track, in that order, from 2006 to 2020. Each had its own unique culture, but their younger staff members all spoke of Phillips in the same hushed tones: Didn’t he drive a Jetta coast-to-coast, sealed into the car, peeing through the floor? I heard Csaba made him wrestle a copy editor. The Escalade piece oh lord the Escalade piece.)

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

In my few years contributing to Car and Driver, I did not live in Michigan, where the magazine is based, and Phillips did not keep regular office hours, so I rarely saw him. We met only once, though I doubt he’d remember. It was during a C/D staff meeting, more than ten years ago, at the book’s annual 10 Best testing. He listened to me say something to the group—undoubtedly genius, unless it wasn’t—and said nothing. Then he raised an eyebrow.

I took this as compliment. Phillips made a career out of raising eyebrows at bits of life amusing or stupid or both. Later that same week, during another staff gathering, I sat next to the man at dinner. We were at Knight’s, the Ann Arbor steakhouse where the cocktails come in pint glasses and carry enough booze to stun a yak. Locals go there to eyeball the kind of fake-wood paneling that your grandmother kept in her basement, and to eat large amounts of reasonably identifiable meat.

I had three gin and tonics that night, then rode home with a friend. By the end of the evening, having miscalculated the combined strength of drinks, I was categorically unable to spell my own name. On the trip home, I spent a moment, eyes closed, counting visible brain cells.

“I sat next to Phillips,” I said, to no one in particular.

“And?” my friend replied.

“You don’t understand. I sat next to Phillips.”

Twenty minutes later, in my hotel room, I returned my drinks to the regional water table, unpleasantly. The evening sits high in memory, a hero met, even though I can’t remember the rest of it.

From his review of the 2002 Cadillac Escalade EXT:

Cadillac’s brand manager says, “Cadillac research showed that there was a real need for the EXT.” A real need for a Cadillac pickup? Really? If so, then here are a few things that I really need: An air-conditioned front yard. Iguana-skin patio furniture. Stigmata. Mint-flavored Drano. Gold-plated roof gutters. A 190-hp MerCruiser SaladShooter. A dog with a collapsible tail. An office desk that converts into a Hovercraft. Chrome slacks. A lifetime subscription to Extreme Fidgeting. A third arm. A fourth wife. A smokeless Cuban Robusto. Reusable Kleenex.

Uncomfirmed rumors, heard through the years: He kept a handgun in his desk. He shot a hole in a press car. He shot a hole in the ceiling of an office during an argument or mishap. (Accident? On purpose? Why not both? When the legend is fun, to paraphrase Liberty Valance, print the legend.) He yelled about everything, except when he whispered. Phillips recently penned a piece for Hagerty Drivers Club magazine about winning the Camel Trophy in 1993; this story leads with the note that he was demoted at C/D for gross insubordination. The exact form of insubordination is not mentioned. I have heard possibilities, but they are deep gossip, and more important, they are about as printable in a family magazine as the stage directions for Emanuelle.

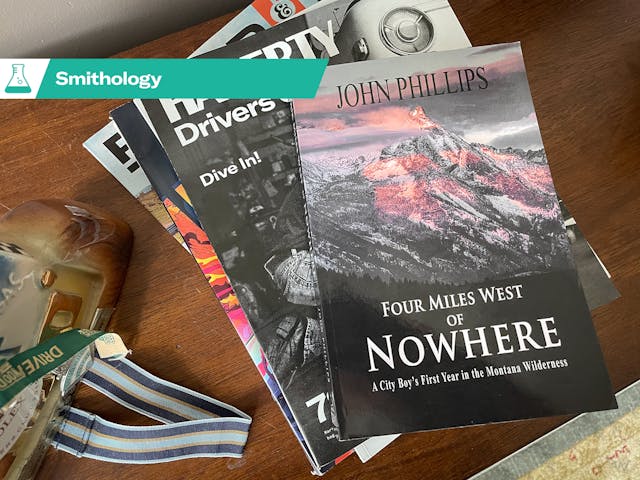

We should probably talk about the book. It is called Four Miles West of Nowhere. The subtitle is A City Boy’s First Year in the Montana Wilderness. Three hundred and ninety-nine pages, Pronghorn Press, 2021. The cover holds a photo of the Bitterroot Range, where Phillips retired after a life in southeast Michigan. The back cover wears positive blurbs from Jay Leno and P.J. O’Rourke. Between lie 12 chapters, one for each month of the year, and 87 snackable and essentially standalone stories of roughly column length. Each of the latter is about learning to live in the middle of nowhere and not get dead. He hints, more than once, that retired life in the woods is mostly writing, and sleeping late, and then drinking beer with your UPS guy simply because the man made the long trek up your driveway in weather.

The book is ramshackle, disconnected, curious, entertaining. Not least because it recalls the sort of honest and punchy travel writing that used to be everywhere, before the bottom dropped out of making words for a living. The man’s work has long been odd populism, Gordon Baxter meets the voices in David Letterman’s head. When I was younger, Phillips’ column headshot in Car and Driver showed only his giant dog, white and fluffy. For reasons I cannot explain, that image made me suspect he was fun to drink with. In retrospect, after years of editing and managing people, I know that individuals like this are never not fun to drink with. I also know that they are generally humans whose assignments must be considered tactically, lest they use the corporate card to buy a case of superballs in Savannah or herd of elephants in Mozambique. I mean those words as praise.

“Editing Phillips,” Eddie Alterman told me, “required nothing but laziness. I never had to touch a word. Master storyteller, master car evaluator. I always felt like he was editing me.” Alterman was editor-in-chief of C/D from 2009 to 2019, a period that included my tenure there. I vaguely recollect him once calling me a master of something, but it sure as hell wasn’t writing.

A reviewer at this company recently noted that Four Miles resembled the work of Bill Bryson, a pleasant but lightly inaccurate image. I have read a lot of Bryson and a lot of Phillips, and only one has ever sounded like Wodehouse through a tab of acid. More to the point, Bryson never wrote a magazine feature story where he drove coast-to-coast nonstop, in motion the entire way, no breaks for fuel or rest, sealed into a Mark III Volkswagen Jetta diesel with a massive auxiliary fuel tank and urinating through a hole in the floor. (Best part of the story: Things went wrong traveling from New York to California, so when Phillips got to California, after days in the car, he simply turned around and made the trip in reverse.)

“It’s the weirdest thing,” I told Alterman. “I can’t stop reading this book, and yet I also keep trying to stop. I’m not sure, but I think that’s a compliment?”

“It’s his brown period,” he said. “I’m a fan.”

Short version: Read some Phillips. Possibly this.

A life in the car business does weird stuff to your head. I know many people in this industry who claim to love the automobile but do not own a car. Some don’t even seem to like driving. I also know a lot of folks who have simply walked away from car enthusiasm after years of 9-to-5-ing, neither happy nor sad, just spent.

“I have come to view cars with near indifference,” Phillips writes, in Four Miles. “Also far indifference.” I don’t blame him, though I hope I’ll never get there. What I do hope to reach is the Bitterroot Valley. He sells the place hard, even though much of the book is about how people die there, seemingly indifferent to risk.

I am not indifferent to Montana death, and I am not indifferent to much in cars, either. I don’t care about the Ferrari Purosangue; I have little interest in the Carolina Squat; the current trends in compact SUVs make me retch. Beyond that, I just want a good story. Cars or not.

This book has very few cars in it, though there are a few Ferraris and many good stories. Reading it made me want to drive west simply to buy a gun and shoot a hole in the roof of the great man’s house. Not as threat, of course. Just a thanks, of sorts, almost poetic, for a life of entertainment.

Try it. (The book, not the impromptu home improvement.) If you don’t like it even a bit, I’ll ship you a SaladShooter with an outdrive on the back, for your trouble. Don’t aim at the ceiling unless you really mean it.