Media | Articles

Smithology: When you’re on the way to fix a 2002, and your 2002 breaks

Welcome back to The Weissrat Chronicles, Sam Smith’s tale of dragging an $1800 BMW 2002tii back to life in off-hours and weekends, when he’s not busy testing new cars for Hagerty. This is the sixth installment in the series, with the chapters best enjoyed in order: One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, and Seven. Shorter updates live on Instagram, at @thatsamsmith and the hashtag #weissrat. —Ed.

It began with Paul’s head gasket. Somewhere in Ohio, on the way from Pittsburgh to Chicago, in his ratty old BMW 2002. My friend Paul Wegweiser likes dragging ass-faced old cars from barns and then driving them around as if they were normal vehicles, neither ass-faced nor deeply redolent of barn, and this is partly why I enjoy Paul. On this particular Friday, he was caning one of these barn orphans across a Buckeye interstate at some speed north of sanity. In a 2002, that means fourth gear and the tach needle wrapped around the post, the whole thing cooking along in seemingly unstoppable momentum, like a pot of water on rolling boil.

Except: Water needs heat to boil, is far from unstoppable. And so, it turns out, was Paul’s crapwagon. Somewhere in the great upper Midwest, that decades-old head gasket took one last look at its surroundings, grabbed its coat and hat, and said, in the simple fashion common to old objects tired of endless whippery,

No.

When he told me this story, several hours later, he was laughing. And so I thought to myself, That’s nice. As the lady who once cut my hair used to say, who doesn’t love a good bang?

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

This was our fourth weekend in Chicago. Four weekends to date with a grand experiment, each Friday bringing a slightly different collection of out-of-towners to my friend Ben’s BMW shop. Mostly without plan. Ben ordered a bunch of steel tubing. Parts were shipped to his door by methods various and sundry. Welding wire was consumed by the crateload. All because a certain individual had decided to save another rusty 2002 from the crusher.

A car far worse than Paul’s. A machine that had not run in years, that lacked floors, subframe mounts, and a list of bits generally required by motive automobiles. A machine so rusty, it should have been thrown away ten years prior.

My car.

You may recall that we have been here before.

Over three previous weekends in this same shop, the BMW had been gifted the vehicular equivalent of crutches. Various orifices in its rusty tub had seen lengths of mild-steel tubing shoved and welded into place. The goal was to get the car on the road cheaply and quickly, but safely. It was not a restoration. Real restoration is neither cheap nor quick. But someone essentially gave me a 1972 2002tii, and I had reasons, so.

It made sense, once, in a weird way. That was months ago. Certain projects just seems to carry their own momentum after a point, like a chain reaction or that feeling you get when you start eating pizza and don’t stop until your stomach is larger than Cleveland.

So much was unplanned. The day Paul’s engine took a breather, I was also on crutches. We could discuss exactly how I managed to snap clean in half the outermost metatarsal in my right foot, but all you really need to know is that homemade margaritas were involved, and it was one of those evenings where you’re wheeling around the house and having a grand old time like a big fat idiot, and then, suddenly, you’re not.

“Oh my,” the X-ray technician had said. Like a parent talking to a toddler. Suppressing a giggle.

“I am going to get nothing done,” I said, dejectedly.

“Well, not for a while, anyway.”

“Are you sure?”

She paused, careful. “Well… that’s for the doctor to say, but you did a number here.”

Across the room and lying prone underneath a large radiation gun, I thought for a moment. “Like, a fun number? Tap-dancing, singing?”

She turned back to the X-ray, no longer amused. “No.”

My brain performed a version of the award-winning act where it hears something it doesn’t like and immediately looks out the window and begins composing fun little songs about puppies.

“You’re not really useful anyway,” Ben said, a few weeks later, when I wobbled into his office. “This isn’t much of a change.”

“Har,” I replied. It sounded like a challenge. Then I tried to carry my laptop bag across the room and nearly face-planted into a shelf.

Ben is a man of subtle gestures. He grew up in Chicago and has the kind of droll personality you get from living through more than 40 Illinois winters while simultaneously fixing people’s salt-eaten daily drivers. He has seen most things Car before and thus trades generally in eyebrow raises.

“Sit down,” he said. “You’re going to break something.”

“I already did. Me.”

“Something valuable.”

I couldn’t sit, though. The car wasn’t done. This is why I went to Chicago in the first place.

Which is partly, if not entirely, why this story is about other people.

Have you ever witnessed a storm building on the horizon, and then just been delightfully humbled as the whole thing rumbles and rolls into town?

The old saw holds properly executed improv as the highest form of skill. Paul is a resourceful sort, a former restoration tech for high-dollar classic cars. He is also lucky. When that head gasket failed on a dark fall afternoon and almost immediately began throwing heaps of cylinder pressure into the wind, he pulled off at the next exit. Through the remarkable grace of God or the clockwork of the universe or whatever deity you subscribe to, that exit happened to hold a parts store, a Harbor Freight, a U-Haul franchise, and a pizza joint. All within a mile of each other.

“I had what I needed,” Paul said later, proud.

Ben cocked his head. “Except a head gasket, at that parts store.”

“Touché,” Paul said, pointing a finger Ben’s direction, as if that proved something.

Naturally, when Paul swung into Chicago that weekend, it was with an empty U-Haul box truck and a nearly dead 2002 on a rented trailer. That night, a small group of people from points distant ambled around Ben’s parking lot. Beer bottles were opened. Someone cracked a handle of gin. And the next morning, while I stood there, hopped up on prescription-grade goofballs for foot pain, everyone got to work.

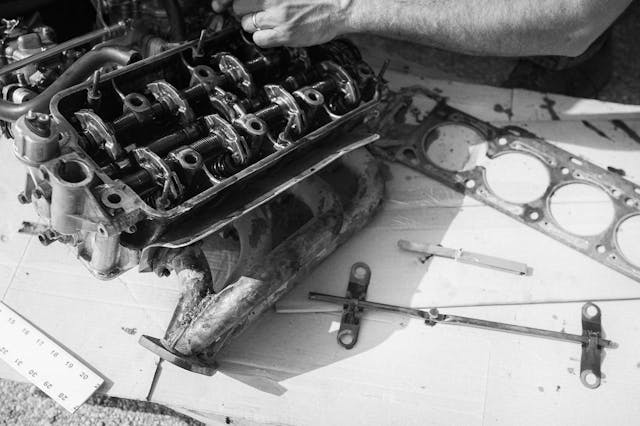

A head-gasket job is a simple act, especially on a 2002, but Paul’s was fun to watch anyway. The job is relatively straightforward, at least once you strip an engine of its intake and ancillaries. At that point, minus the vagaries of disconnecting the valvetrain from the engine’s bottom end—it all depends on the car—you’re free to unbolt the head. The 2.0-liter four-cylinder in a 2002 uses an iron block but an aluminum cylinder head, and while that head is not small, it can be lifted off the block fairly easily.

Pull a cylinder head, you’re left to stare down at piston tops. I’ve always liked looking at open cylinders—there’s something soothing there, knowing the work that happens inside. I had not, however, previously stared into a headless cylinder block while having neat little hallucinations about the strange and magnificent nature of generous friends.

Maybe it was the painkillers. (Arms-grade stuff. The kind where you talk to your toes for a bit as they kick in.) It might have been the fact that, four weekends into this silly endeavor, people just kept showing up at Ben’s place, without being asked, to work on my hurt little dirtbomb.

Painkillers were pretty good, though.

I lost count of the bodies in the shop. Six? Nine? Fifteen? Ben’s service bays were occupied with other projects, so Paul and Carl began decapitating Paul’s car in the parking lot. Larry showed up and began sifting through spare sheet metal. Owen began cleaning something. Two seconds with a straight-edge showed that Paul’s cylinder head had warped in the wake and heat of the failed gasket, so it needed to be decked. Carl kneeled next to the front bumper and proceeded to relieve the head of its plumbing.

I took a few pictures and then crutched carefully into the shop, where my 2002 sat. Long-term projects can play tricks on your head; timelines compress and drag out beyond their actual space on a calendar. When I trailered the BMW to Chicago, months prior, it needed ages of mechanical attention and was almost existentially rusty. The car was now noticeably less rusty but even less existentially sound; the tub held something like rockers, floors, and subframe mounts, just not in the traditional sense. The machine that had left Germany 50 years ago in spot-welded precision was now maybe 50 percent less precise, its bits held together by a garter belt of mild-steel pipes and sheet-metal sarcophagi, a series of oxide wounds alternately caged around or exoskeletoned out of structural relevance.

It now looked vaguely like an actual car. Probably. From 20 feet away.

A swarm of activity began as I stood there, as it had on those three other weekends. This time, however, I was a fixed point, not part of the swirl. Larry lay down under the front floor and began busily excavating one of the rotten frame rails, yanking out dirt and rotten metal. Tim started poking at the right rear quarter, measuring something. Ben walked up to the right rear window, squinting suspiciously at one of the car’s rust holes. He and Tim conferred on something for a moment, a kind of closed-shoulder huddle, two engineering degrees muttering near the rear fender. I briefly heard the words “can you do linear approximation of that pipe?” An angle grinder lit off in the background.

Having a Jewish mother but also a conscience, I felt almost immediately guilty. I had worked on this car along with these people, every one of those weekends. The project wasn’t theirs or mine, it just was. Stillness seemed wrong.

There were initial attempts at protest, of course. I hobbled around and knocked my crutches into things, stumbling through the close quarters of Ben’s shop, trying to keep people from doing work, muttering earnest things like, Stop it, I can’t help, this is silly, Paul’s car has real needs, we’ll deal with my pile in the next trip, why don’t we all just walk outside and grill some food for lunch and drink a morning beer and not worry about it.

Lather, rinse, point at anyone with a tool in their hand. No takers.

Owen, strolling by one of these vents on the way to the other side of the shop, finally shut me up. Owen is in his early twenties, not far out of college, a software engineer. He overheard the tail of one of these pleads and went into a little palms-up shrug, like Alfred E. Neuman.

“What fun is that?” Impish grin.

You ever get the feeling that literally every single one of your friends is smarter than you?

A breaker tripped, and I decided to roll with it.

Paul’s cylinder head went off to be decked shortly after lunch. It was a Saturday, and Ben’s machine shop was closed, but Ben hopped in the car and drove there anyway. An hour and a half later, he was back, with a fresh cut on the head. Ben made it clear to Paul that he had called in a favor. Being a clever man, he did so in a fashion that hinted at mild annoyance while also making everyone laugh.

“I hope you know, I don’t do this for everyone.”

Paul squinted at Ben in what was obviously gratitude but unlikely to be announced as such. “Oh, I know.” Then he took a drag on his cigarette and eyed his car as you might eye a dog that has just taken a dump on the carpet.

The hurricane of activity resumed. While Paul’s engine went back together outside, Carl bent new brake lines for my rear subframe. Owen began mocking up a steel tube to mate what remained of the 2002’s rear wheel arches with the steel tubes now passing for rocker panels. Larry got to welding on a bit of the floor. (Previously: Football-size holes. Now: Something … less than that.) I tried to busy myself with small jobs and bench work, but everyone else moved faster and wasn’t attached to a pair of derpy aluminum sticks in a cramped shop. I mostly just got in the way.

Around 3:00 that afternoon, I crutched over to Larry, who had moved on to stitching together a new sarcophagus for the driver’s frame rail. Larry is a recovering corporate engineer who quit his job several years ago to open a restoration shop in Minnesota. He is exceedingly polite and does genuinely excellent bodywork. I hobbled up just in time to see him kick a foot-long piece of rusty steel out from under the car, where he was lying.

“Just curious,” I said, leaning down. “How much of a pain is this rail for you?”

He climbed out and stood up, brushing off his coverall legs. “It’s not bad. Just time. You have to get through the rust and the dirt and the paint and the tar and … it just blows up, lights the whole thing up. So you kind of do one pass of weld to clean it out, and then another to actually weld it. You have to sort of make it up as you go along.”

“There isn’t an ounce of this project that hasn’t followed some version of that pattern.”

He chuckled. “You knew this going in, of course.”

“All I knew was that it seemed really stupid to do anything other than junk this thing, so that seemed like a good reason to not junk it. Honestly, I’m still just shocked everyone’s working on it. That they’re not drinking a beer or doing literally anything else. Even standing around.”

More drive-by zingers: Paul happened to be walking by at that point, carrying a piece of steel to the back of the shop. He pointed at the car and then me and then back to the car and back to him, repeatedly, with a big, smarmy grin.

“I mean, what can I say? People like animals!”

I had been sipping on a bottle of water, so I hucked it at his head. He ducked and it missed, but the open bottle arced a geyser over the shop floor. Ben scowled and told me to clean it up.

Everyone’s a comic.

A few feet away, Carl piped up, in the gentle manner of an older man who also runs a restoration shop (California, BMWs, mostly vintage) and has also seen everything.

“Don’t be silly,” he said. “It’s not about the car.”

Carl is Owen’s father, incidentally.

That feeling again.

Sunday morning, his car once more assembled and running, Paul walked over to my 2002 and hung a new center bearing and flex disc on the driveshaft. Then he finished rebuilding the brake plumbing while Carl and Owen bolted the diff down. All straightforward work, but it would have gone faster with another pair of hands. Mine just sat there, in a folding chair on the shop floor, as they had the day before, on my right leg, which was propped up on a bucket to stem the swelling. The pills had worn off and my foot was screaming, but I didn’t much think about it.

Humility is a hell of a painkiller.

As I write these words, months later, I’m out of the cast and walking again. My right foot is still a little sore, and one toe has a habit of going numb at odd times, but that’s trivial stuff. You deal with injury remnants like you deal with strange weather, and weather rolls in and out of your life in the same manner as people. Sometimes, as with a broken foot or a blown head gasket, you don’t see things coming. Then the sky is clear again or the bone is healed, everyone back to normal life, and memory is the only thing left.

Along with, in this case, a rusty old pile of German rat-car disaster rapidly beginning to look like it might soon become a rusty old pile of lightly mobile German rat-car disaster.

Maybe.

Still much to do.

Fingers crossed.

To be continued…