Media | Articles

Smithology: Until you one day wake up and have actually gone someplace

Welcome back to The Weissrat Chronicles, Sam Smith’s tale of dragging an $1800 BMW 2002tii back to life in off-hours and weekends, when he’s not busy testing new cars for Hagerty. This is the last installment in the series, with the chapters best enjoyed in order: One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, and Seven. Shorter updates live on Instagram, at @thatsamsmith and the hashtag #weissrat. —Ed.

At 11:52 in the morning Chicago time, on Sunday, October 11, structural metalwork was declared complete.

A lot of people did a lot of things to get through 2020. For my part, some friends and I went all goober-weld obsessive and gave life to a dead old BMW for virtually no reason. As I’ve said before, the car should have been thrown away. What do you do with a machine that almost certainly lived through a saltwater flood and is missing 80 percent of its body structure below the seat mounts?

What if you bought said machine on a whim, because you’re a softie and the seller was a nice guy and the car was cheap as old socks?

Follow-up question: If you’re not a softie for lost causes and old loves, are you even a car person to begin with? Wouldn’t your money be better off in the bank?

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

So much on the car was gone. We didn’t bring all of it back; that would have been almost impossibly stupid, and just as important, I didn’t have the money. So we went somewhere else entirely.

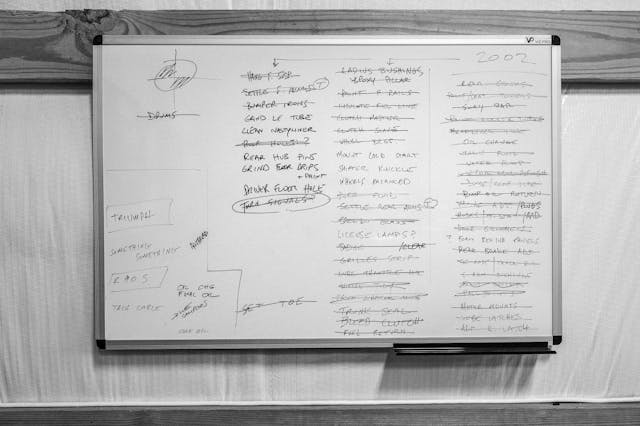

I bought this BMW last summer. You can read about that here, if you like. The real work went down last fall, a truly massive amount of slapdash welding and exoskeleton installation—bracing tubes and patches—over six weekends at a friend’s shop in Chicago. At the end of each day, we’d all sit outside in the parking lot and eat, watching the sun set over the city and trying not to think about the rest of the world.

Early in this project, someone jumped into the comments and expressed concern for my liability; nonfactory “restoration” done as a larf can leave you open to lawsuits in an accident. I meant to reply to that comment and didn’t, but it’s irrelevant. I long ago decided that this car will either leave my hands as scrap steel, cut up in a Dumpster, or it will never leave my hands.

A quick summary of what happened in Illinois:

Sills: Rotten factory rocker structure excavated and replaced with rectangular tubing the length of the car, plug-welded into the cabin sill from beneath.

A-pillar and rear-subframe reinforcement: In the front, round tubing was built into an L-shape and used to reinforce the weakened A-pillar structure, creating something like a load path for the rocker tubes. A similar idea was used in the rear.

Rear-subframe mount structures: The factory ones were gone. Air and oxide dust, evanesced. New mounts were built and welded to the floors using aftermarket repair panels.

Shock-tower patching: A sarcophagus of steel patchwork was created around the original shock towers, which had split and torn from rust. Picture what they did to Chernobyl—the bad is still in there, only now it won’t come out for a bit.

Floors: Various large holes were patched, sloppily, to be less… holey. There may still be a hole or two and some weld drips, but who’s counting?

Details replaced, sourced, or repaired: Windshield, driveshaft, flex coupling, driveshaft center bearing, gearbox mount, motor mounts, trailing arms, rear subframe, rear subframe mounts, main (high-pressure) fuel feed line, front bumper, strut bearings, wheel bearings, wheel cylinders, calipers, rotors, brake flex lines, most of the rigid brake lines, brake master cylinder, and there was more. You get the picture.

And then, on November 16th, at 10:44 in the morning, I drove the thing onto a trailer and dragged it the 550 miles to my house in Tennessee.

You do not get to see our awful work in detail. Not unless you spot it on the road in the months ahead, or at some car show I have entered for laughs. If that happens and you are impressed, find me. I will buy you a drink and a hamburger and ask why your mother dropped you on your head when you were little.

I have driven it! On real roads! In traffic! It acts like a half-decent car of not-inappropriate speed and ability! A combination of facts that shouldn’t be surprising but manages the trick anyway. I first drove the car on the day I bought it, from the seller’s driveway to a U-Haul trailer down the street. The subframe creaked in protest and wind blew up through the carpet. A couple of days later, in my shop, the subframe mounts crumbled away under the poking of a screwdriver.

It’s good now. A word that sounds strange to use in this context, but what else do you call a machine that tracks straight at 80 mph, hands off the wheel?

My wife, when I shared this fact: “Are you sure you want to do 80 mph in … that?”

Me: “It’s a real car!”

Her: “Don’t put the kids in it.”

Me: “You’re just saying that because they’re healthy.”

When the car hit Illinois, the A-pillars lacked certain bits of undergarment. Each sill was also oxygen from the base of the seat rails to the pavement outside, a three-inch-tall tear longer than the door above. The doors now latch on a finger. One of those delightful little details in a complex project that ends up more satisfying than you expect. (For the record, I had to shim and tweak-hammer-twist-bludgeon the right door to get it to close without the striker hanging, because the B-pillar was, as they say in spy novels, dislocated.)

(The left door, though: Shut like buttah, from the beginning.)

You know that feeling you get after eating a satisfying but unhealthy meal that took hours to prepare? That moment where the table is finally empty, and the only job left is the dishes?

You ever just take a minute right then to lie on the floor and moan at the ceiling?

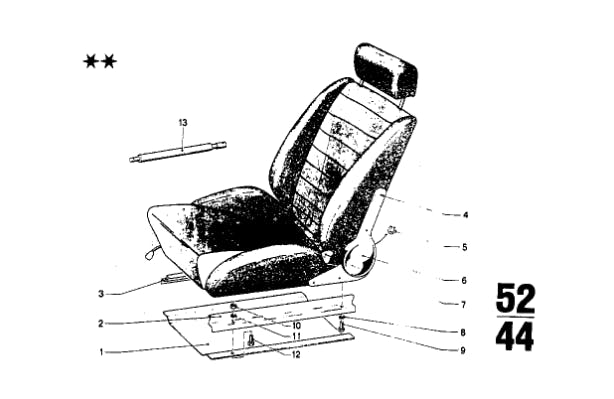

With most life-altering decisions, the end result rarely matters so much as the doing. Which is why I want to take a moment to tell you about the seats. I bought them online late one night, after much thought, on a dangerous mix of dark-roast coffee and Sour Patch Kids. In the late 1960s, German seatmaker Recaro produced and sold a number of different sport and racing buckets. The company’s early offerings made novel use of foam padding—horsehair and metal springs were far more common—and large bolsters, to help a body stay in place. In this period, some carmakers bought Recaros in bulk, for factory fitment. Porsche famously used a particular Recaro sportsitze in the early long-hood 911 S; the same seat was offered in early 2002s. Original versions of these seats in good condition now command five figures a pair.

The BMW came with an absolutely roached set of Flofits installed maybe 40 years ago. The fabric was torn and the foam collapsing. I spent a lot of time thinking about those seats. A margarita helped, once. A savings account was eyed. Budget retconning occurred on grand scale.

Did you know that there is an Italian seating firm called BF Torino, and that this company will ship you a set of reproduction Recaro copies in a mere two weeks? Like the rare Borrani steel wheels the BMW now wears, those seats represented what the tii looked like and meant in my head: period DGAF rat, plus a few nice touches.

It’s remarkable, what you can convince yourself is necessary, when absolutely nothing is necessary. Moreover, I figured, if you’re actually going to drive a thing and use it to go places, you don’t skimp on the skeleton holster.

What I didn’t then realize was how the car was mutating into a different kind of project. It started off as a way to kill time and salute a period when cars like this were cheap and disposable. You don’t put $2000 worth of seats in a car you built for a laugh. Or maybe you do.

That final weekend in Chicago amounted largely to cleaning and interior reassembly. In a fit of optimism, someone declared the metalwork complete—the car still in need of mechanical work, but safe to drive. We sat down that afternoon and had a beer. Paul, the industrious type, rolled under the car to attend to some last-minute detail on the driveshaft. The guibo wore new hardware, bright and shiny, standing out against the lightly undone rot.

I liked that.

Once, a long time ago, I wanted to keep vehicles forever. I have since and over the course of many purchases learned that I am not this person, save the odd exception. There is for example the Mercedes W108 that my grandmother bought new, that my parents left their wedding in, that I left my wedding in; that car is in Dad’s garage and will eventually come live with me. There is also one particular motorcycle that has accumulated many miles in my ownership and will stay in the house, pickled in the living room, long after my body is too old and frail to ride it.

Everything else has left the building, as they said about Elvis. Always to make funds or time or room for some other interest.

An old friend named Ben helped make the white car happen. It was his shop and his generosity with time and knowledge that helped the car come back to life; he was the one who told me that the idea wasn’t stupid. Or maybe that it was just stupid enough.

Late in the process, just before I took the BMW home, we were talking in his office. For some reason, I flashed back to watching him reinforce one of the rear spring perches.

“I’ve been thinking about that spring perch,” I said. “How long it’ll last, you know?”

Ben shrugged. “I don’t know,” he said. “If it breaks, we just fix it again.”

Projects always produce a certain feeling. It’s stronger if the machine in question was dragged into your life half alive, barely able to hold itself off the ground. You take stock and you get to work, and sometimes that work takes months or years. Small projects become big projects, simple jobs stretch out in that uniquely impossible fashion—How on earth can it take me three weeks to find the garage time to spend 90 minutes hanging the front suspension on the thing?—but you move ahead anyway.

And then there is that delicious and surreal moment when you let out the clutch. When the whole stack of hours moves for the first time, unexpectedly light on its feet. You lose track of time and just glide along, your body filled with air, and you are not thinking about when the grocery closes today or whether the kids need picked up from school or if the laundry is backing up for the fourth time this week, nothing like that at all, and the whole thing feels like a gift, it is a gift, there is no asking why or how or whether it was all worth it, because of course it was worth it, how could it not be, not with a feeling like this, unique and so rare and brewing, buoyant as helium, all the way down in your deepest of bones.

At which point you stop for a second and notice that you are much further from home than you thought.

There are miles to go. Mostly nearby, for now. Then more venturing, farther and farther, as you do. Until you one day wake up and have actually gone someplace, gone there in this one-time hulk made alive, this improbable little pile of work and memory that you didn’t know you needed in your life until the day it showed up. Until it invited itself in and you thought, I mean, I wasn’t expecting guests, but.

Time passes. You may wonder about letting go and selling. Then something shifts. Who kicks family out of the house?

The first part of the job is over.

Time to get to work on the rest.