Media | Articles

Smithology: The thrill of Kenny, the agony of the foot

The Corolla smelled like burnt armpit. The immediately identifiable funk of a nearly new but entirely used-up rental car, equal parts mildew and blatant abuse. This was in addition to the broken hubcaps, the sticky food residue covering the dash, the wavy body that seemingly polished with a broom full of sand. The steering pulled subtly to the right in a manner that suggested some previous driver had made a game of running the car into ordinary street objects, like trees or a Walgreens. When I took delivery, the front seat was covered in human hair. Twenty-six thousand miles on the clock, and it might well have been half a million.

Still. A cloudless day. My phone was busily streaming a series of cheerily disposable pop songs into the stereo. A recently emptied Taco Bell bag sat on the passenger floor. Eight hours later, I would be in Chicago, where I would retrieve my truck from storage and use it to tow home a particularly beat-up old German car. Knoxville, Tennessee, to Illinois. Entirely interstate. Boring as dirt, even by the scale of Midwestern road trips.

The whole thing felt like a gift.

If you can possibly maybe for the rest of your life even a little bit stand it, I highly recommend that you never, ever break your right foot.

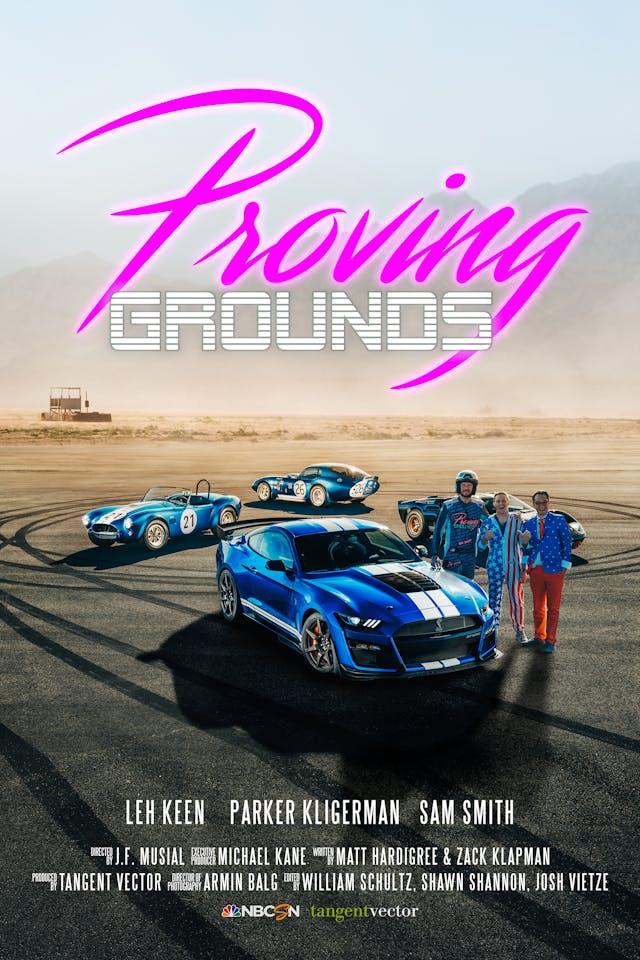

I drove nothing for six weeks and went basically nowhere. This being the year 2020, most of that time was spent in the house. My injury was not rooted in brave acts or heroism, unless you count accepting one’s own idiocy as heroic. (Don’t.) This past September, I traveled to Connecticut to film an episode of a small TV series for NBC Sports. For the past three years, that network has aired a moderately improvised—and co-hosted by me!—half-hour program called Proving Grounds. Three seasons of 30-minute episodes, each one packed with new cars reviewed in unorthodox ways, plus a few doses of history and science.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Most people I know to have watched this program have done so in bars. This is good, really, because although I generally create only unfathomable genius best experienced through the unflinching and crystal lens of sobriety, I also comprehend the nature of television. Which is to say, if you are going to air, for example, a special episode featuring only American cars and a stunt where a grown man dons a bald-eagle suit and dances in the back of a Chevy truck against a firework-filled sky while the driver eats a hamburger in slow-motion and said truck tows a backhoe because—well, the only word here is freedom—you might as well pad the deck. Grab people when they’re a beer or three gazeboed.

In the past, we have filmed this goofery in the California desert, outside Palm Springs. September’s shoot took place at Connecticut’s Lime Rock Park. Dinner on the final night was a taco bar set up in a rented house nearby. (Disclaimer: Cast and crew were all COVID tested before filming, living and working in an isolated pod.) Someone made a pitcher of almost painfully delicious margaritas. Five minutes in, I meandered to the kitchen to microwave a tortilla and got distracted by a bottle of bourbon that some previous renter had left in the back of the pantry. Inordinately excited (free bourbon!), I grabbed the bottle and began walking back to the table, eyeing the label as I did. An instant later, I realized the bottle was nearly empty (light disappointment!) and smelled like the inside of a gas-station toilet. (Further disappointment plus resignation! And the shrugging knowledge that we were almost certainly going to use the stuff anyway!)

An instant after that, eyes still down, I was tripping into the house’s recessed dining-room floor and listening to the audible snap! of the shaft of the fifth metatarsal in my right foot.

Loud thing. Sounded like a chopstick. Ever break one of those, then fall flat on your face?

One of my co-hosts, a hugely talented precision driver named Leh Keen, came over and informed me, in his polite Georgia drawl, that I should probably just walk it off. Then he stage-whispered to one of the crew that SAM DOES NOT HAVE A PAIN TOLERANCE WE SHOULD JUST GIVE HIM MORE MARGARITAS.

No one pretended to hear, except the first guy to hand me a margarita. Possibly also the third. The first guy was making a joke. The third one was helpful.

The orthopedist prescribed six weeks in an immobilizing cast boot. This plastic-and-foam thing the size of a Winnebago. The first three of those weeks came on crutches, and the latter three featured me clomping unsteadily around my house in the boot like some kind of Frankensteinian cross between the Six-Million-Dollar Man and a guy who escaped from the mob before they could finish installing his feet in cement. My wife and kids heard me coming and generally left the room, except my five-year-old daughter, Vivien, who finds her father hysterical no matter what and cackles at her own flatulence and is thus the greatest intellect to have ever lived.

Embarrassing confession: I had never before broken a bone. The frustration was palpable. Not that it should have been—far from it—but emotions don’t always ask for an invite to dinner, right?

I feel sheepish now thinking about it. After all, what’s six weeks? Sure, I spent October basically indoors, and walking was so painful and cumbersome that I saw one of my favorite months mostly through a window. In retrospect, who cares? Everyone knows someone who’s been laid up for weeks or months in the wake of an injury. The editor of this site alone has fractured more bones than he’s had hot meals. Several years ago, my friends Robin and Charley each suffered traumatic brain injuries at about the same time and had to learn to walk and think again. Both attacked the task with gumption and enough positive attitude to shame Tony Robbins. What kind of person witnesses that suffering and resilience and then gets all grumpy when their foot goes down for bit?

And yet I grumbled. The nature of being human, where few problems can, in a moment, seem larger than your own.

When the doctor told me I could ditch the boot and start wearing shoes, it was like Christmas. Walking would be painful, he said, but a day and a half later, I was hobbling through the local airport and renting that Toyota. An exit. Joyous, even as the bone screamed.

The weirdness set in the moment I hit the key. The exquisite pain was expected. Less so the massive atrophy of muscle and perception. The loss of mental and physical resolution seemed somehow offensive: Gas pedal as on-off switch! No subtlety to wheel inputs, the rheostat of control gone! Most of a life practicing a skill, and I may as well have been 16 again. And who knew 35 mph was entirely too fast for human travel? At that insane speed, trees whizzed by as if they had to be somewhere, too fast to see. In a past life, in another job, I track-tested an ex-Le Mans McLaren F1 GTR and hucked the car into a 130-mph corner immediately aware that I had chickened out, a few ticks too slow; in the Corolla, 40 mph was screaming-death-monkey stuff, Toyota where eagles dare. Even though I knew, logically, that the car was basically asleep.

The world made zero sense. Leaving town, I set the cruise control and fought to stay on a constant vector in a single lane. My eyes couldn’t stay fixed on the horizon, or even the end of the road. Panic braking seemed out of the question, so I drove ten under the limit and away from everybody, uncomfortable and spooked. Fifteen miles later, I looked down to see my foot back on the gas. The speedo was 20 mph over state max and I had absent-mindedly begun left-foot braking into off-ramps.

Not normal, but not the other thing, either. Proof that the brain adapts to surroundings even when you don’t ask.

We are so used to the things we get used to, so genetically wired to be shocked by sudden change. You go through your days without really thinking about how being a functioning member of society isn’t proof of some inherent talent or exceptionalism, just accumulated practice. Lose the practice, the ability goes to smoke. Maybe it’s some leftover from childhood, where the gentle and purposeful progression of school programs you to expect a ramp-up for any shift in sands. Only that’s not how the world works. In real life, things just flip one day, boom.

Crossing into Illinois with the windows down, just south of Lake Michigan, my phone was still shuffling randomly through songs. For reasons known only to chance and algorithm, a new tune hit just outside Chicago, as I slowed for traffic. Gently lilting music, then a few words too close to home:

And yes, it’s true that I’m not the man I used to be

Oh Ruby, I still need some company

Kenny Rogers. “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town.” 1967. Didn’t even remember putting it in the playlist.

I hit the knob and shut it off.

Kenny never much rang my particular bell, but you throw strange things into a streaming queue before a trip because why not, right? Then they pop up on shuffle one day and you feel maybe a little silly for reading too much into the lyrics, a bit too on the nose, and who calls a crappy old rental car “Ruby” anyway?

Okay, maybe me. Just for a moment?

The cliché, naturally, is how mistakes can remind you of your own fragility. That glimpse of what’s at risk if you really screw up, break more than a foot, get stuck with figurative keys in your pocket but unable to go. Nobody likes wearing out; if you’ve never seen it in your own clothes, you tend to forget it happens.

Sad song. Good day, though. Could have been better, of course; they always can. But in that car, on that highway, surrounded by glacial traffic and rotting Toyota, I found myself thinking, and for what certainly wasn’t the first time this year, that it also could have been a hell of a lot worse.