Media | Articles

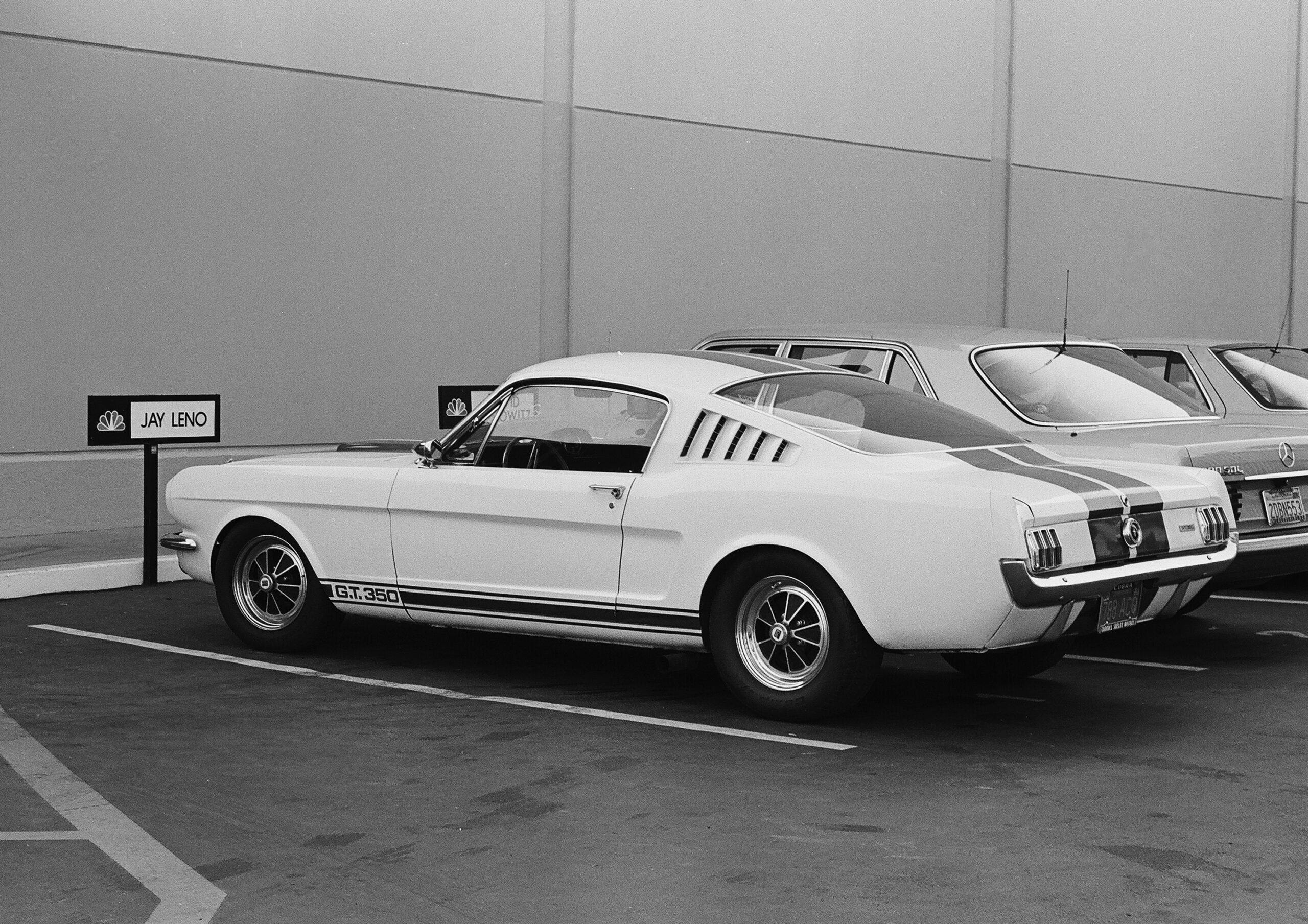

Smithology: Mustang memory, Shelby snapshot

Sam’s columns are usually around 1500 words, a few minutes’ reading. Sometimes, though, he trips a breaker in his head and goes long, and we let it run. This is one of those times. It doubles as one of our Great Reads. Enjoy! —Ed.

***

You probably know the story. If not, maybe the name rings a bell. At minimum, you can probably pick an early Ford Mustang out of a lineup.

The shape means something. Add that name, it means something else.

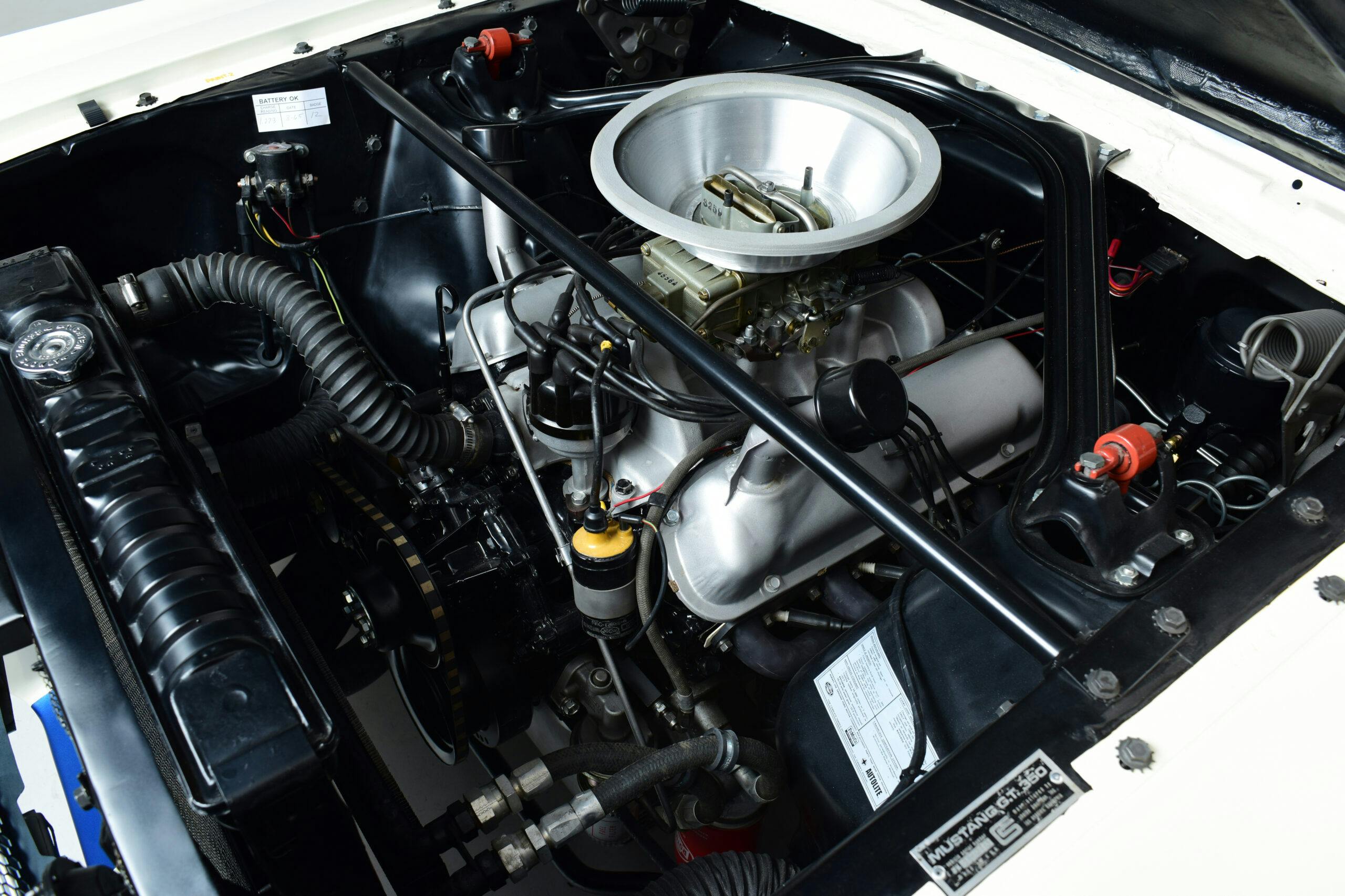

Shelby American built just a few thousand GT350s for 1965 and 1966. Thirty-four of those machines began life as race cars, a GT350 R, the bare-bones factory competition variant. Shelby people call them R Models, and every single one is now worth seven figures. Which is not to paint the ordinary cars as less than special. Even in road-going form, they were Fords but also not, Mustangs but also not, an uncommon version of a common object.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Google says this site has run the phrase “Shelby GT350” on more than 500 separate pages. We come back to that name for many reasons. For one, our readers love Mustangs. Still, the GT350 story is different.

Unlike many high-dollar 1960s performance cars, the Shelby was not hammered into life in some artisan’s shed; it was based on a Ford sold in the literal millions. Its origins hold lessons on the power of romance and origin, and on how a simple marketing exercise can, without much planning, come to represent something far more important.

A few nights ago, I was digging through an old hard drive, looking for snapshots from an old vacation. In the process, I stumbled onto a long-forgotten folder of photographs of the first GT350 I ever drove. That folder also held an interview I once conducted with Chuck Cantwell, the GT350 project engineer at Shelby American.

The thoughts and images below—some of the Cantwell chat, bits of trivia, some drive notes—contain no grand thread. There is no great reason behind their assembly, not even an anniversary to celebrate. If you do not already love the car in question, you will not find yourself converted, may wonder why I spent so much time on a simple Ford.

All I can say is, the kind of person who can unconditionally love an old machine is also often the type to get lost in memories and story. Perhaps you can relate.

***

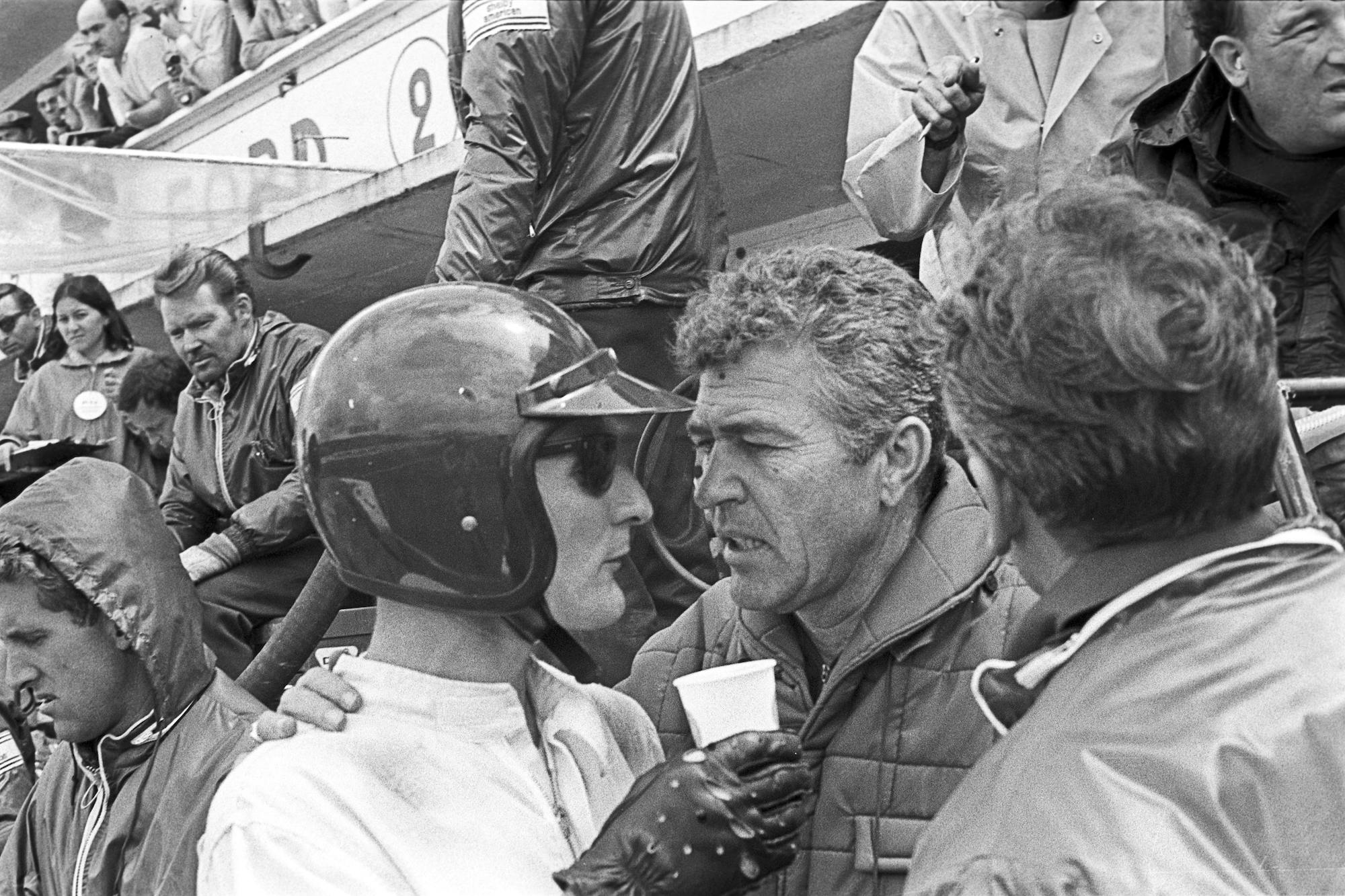

A grinning man in a suit and his two most famous products. Carroll Shelby turned 42 that year. He looked nothing like Matt Damon, who played him in Ford v. Ferrari. That film, released four years ago, was set in 1966. The photograph above was taken the same year.

He was a salesman, of course, and a former racing driver, and a back-of-napkin engineer. More remarkable, though, was his eye for talent. The names he hired were never household, but most are titans of this country’s golden era of motorsport—men like Cantwell, Ken Miles, Phil Remington, Pete Brock, and John Morton. Machines they built, drove, or engineered hunted down speed records, wins at Le Mans, America’s first FIA GT championship, and road-racing titles the world over.

In retrospect, the success of Shelby’s first Mustang was no accident. But the car was not his idea.

Chuck Cantwell: You asked the question earlier about Shelby and the Mustang program. Shelby didn’t really want to. I mean, he said outright, “I didn’t really want to do this program.” He was telling me this as I was being hired. But it was sort of a favor for [Ford vice president Lee] Iacocca.

Iacocca had provided him engines for the Cobras, and so he sort of owed him one. And Iacocca wanted to do a performance car, and they had the Mustang fastback [launch] coming up….

Sam Smith: Lido. Mustang, Pinto, 1980s Chrysler—the guy made such a dent on Detroit.

CC: So Shelby thought, well okay. But once it was going, it progressed along pretty good.

Peter Brock, the designer behind the Shelby Cobra Daytona coupe, tells a good version of the GT350 origin story. It features a healthy dose of Carroll being Carroll—not the grinning Texas-drawl public persona but the real-life man, which is to say, less Matt Damon and more slight-of-hand deal-closer with a knack for making the most of a situation. And a certain . . . moral flexibility.

Two phone calls occurred basically at once. The first was with Iacocca. Dearborn wanted the Mustang accepted for amateur and professional road racing in the United States; the main sanctioning body for those events, the Sports Car Club of America, said no. The Mustang was not a sports car, it said.

Iacocca asked Shelby why. The latter didn’t know. He called the head of the SCCA, a friend named John Bishop. Sports cars are two seats, Bishop said. Well, Shelby offered—what if we build them here at my shop in Venice Beach and pull the back seats? Fine, Bishop said.

Shelby got back on the horn with Iacocca. Done, he announced—only hitch is, you have to let me build ‘em.

Iacocca agreed, probably because the Texan was convincing. He was always convincing.

“It turned out to be the biggest deal he ever did with Ford, and it must have taken all of one minute. That was Shelby, one of the most charismatic smoke-and-mirrors promoters in the history of racing.”

— Peter Brock, in Colin Comer’s excellent Shelby Mustang: Fifty Years

There is more to the story, of course, and the end result offered more than just a deleted back seat. A quick internet search will spit the stats—that first 350 sold well and won an SCCA championship. More important, it gave Ford reason to build similarly named descendants into the modern era.

Advice from this corner: Do not stop at Googling. Find yourself a copy of Shelby Mustang: Fifty Years, and not just because Comer is a former Hagerty employee and a good friend, or because your narrator has a small byline in it. (A guest column on page 218, thank you Colin.) Few histories of the car paint its stories or people as well, or lean as hard on killer archive photography and conversations with those who were there.

Sam Smith: The Mustang began life as a rebodied version of Ford’s Falcon sedan. And yet few people were champing at the bit to race a Falcon.

Chuck Cantwell: There had been some Falcons run, they didn’t make great platforms. And there were some [stage-rally] Mustangs at the very beginning. So Ford had done a little bit of development and testing, had some ideas about what to do. I mean, one of the very early Mustang prototypes had been taken out to Waterford [Hills, a small road course near Detroit], and a couple of guys had run it out there. They had some ideas about what the car needed.

SS: People in period said the cars took some work to handle alright, but not as much as you’d think.

CC: The street [GT350] was three-quarters race car at the beginning. We did development testing after we got the first one together. The traction bars and big front [anti-roll] bar were already there . . . the configurations all worked, there wasn’t much to do except dial it in. It didn’t present many horrible problems we had to solve.

The result was famously named after the distance between Shelby’s race and production shops in Los Angeles—Grand Touring, 350 feet. A decision was long in coming; Shelby had grown tired of the meetings. Exasperated, he asked an employee, Phil Remington, how far apart the shops sat.

***

Some will tell you it’s awful—a 1960s American car, fine in period but terrible by modern standards, no brakes, a mess in a corner, and so on. Other people insist the car is fantastic, full stop. If you are me, you climb behind that wheel for the first time assuming the experience will be somehow both, because that is often simply how history and myth and reality and old cars come together.

The first GT350 I met was a ’65, an early one, unrestored, virtually stock and all but perfect. The car had been mechanically sorted by a Shelby expert, assembled and dialed the right way. Save a heavy brake pedal and some clunking from the locking diff, it was a marvel—fast and solid, the good kind of work on a tight back road, clearly vintage but with none of the old-Detroit bad habits.

A friend drove a similar car, called it a V-8 Miata with a live axle. He wasn’t quite right, but he wasn’t far off, either. It felt like . . . a sports car?

Small and nimble, with feel a priority. Which is not exactly how most people describe 1960s pony cars, Mustangs and Camaros, but hey, there is occasionally strange alchemy in this world, and we are sometimes best off simply drinking it in.

I was flabbergasted. By time I tried that ’65, I had been testing vintage and modern iron for years, from prewar race cars to 1000-horse exotics. That period had included a smattering of first-gen Mustangs, from 500-horse restomod fastbacks and 100-point Shelby clones to a bone-stock six-cylinder notch with less torque than a bowl of yogurt. All were fun in their own way, but none pushed the same button.

It sounds crazy, of course. Mustangs are Mustangs, right? Mass-produced and simple, mostly the same? Some of the appeal was probably in my head. I was curious, though. After, I talked to the owner, that GT350 expert.

“Is the steering this nice on all of them? Manual but not too heavy, buckets of feel? Do they all ride that well? Cruise hands-off at 90? Where are the bad habits?”

“Some of them get close,” he said. “The one you drove is special, though.”

“How?”

“Not really sure, to be honest? It’s just a really good one. But they’re all pretty good, if they’re built right.”

***

Shelby had told Iacocca that R&D for the road car would cost $15,000—around $145,000 in modern dollars. In August of 1964, Iacocca sent him two notchback Mustang coupes and $1500. Carroll being Carroll, he proceeded to call Goodyear and Castrol, each of which chipped in five grand. The first 100 production cars—the SCCA minimum for competition legality—were finished by fall of ’64.

Critical to all this was a man played on film by Christian Bale. For years, the name Ken Miles was something of a password in certain circles—if you knew of him, you had likely read the books, knew how Shelby worked, loved the cars just as much for the stories as how they drove.

Sam Smith: What was development like on the race car? Miles basically just handed you the R Model to sort out?

Chuck Cantwell: It was just a matter of getting the thing right, the chassis settings, and deciding what tires to use. There wasn’t much choice in tires at that time. We used a stock-car tire [at first].

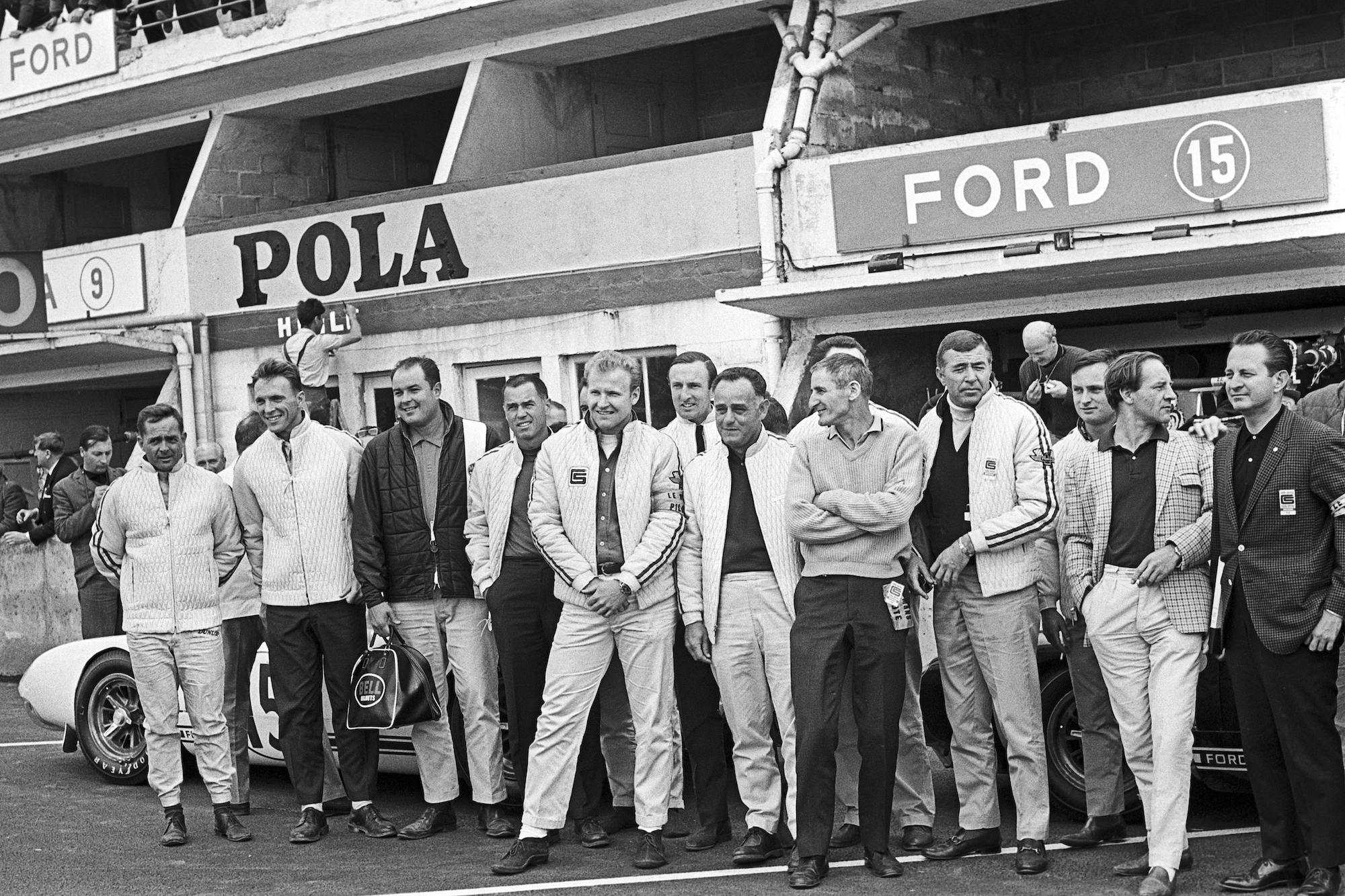

Miles was English, a racing driver and mechanic but so much more. While working for Shelby in California, he helped develop the Cobra, the GT350, and the Ford GT40s that went to Le Mans; as a development driver, he is generally viewed as the indispensable chassis-magic core and soul of Shelby’s operation; as a racing driver, he won Daytona and Sebring and nearly won Le Mans overall.

He died in 1966, just 47 years old, killed in a 200-mph crash while testing a prototype GT40 at California’s Riverside Raceway. One year later, a version of that car won both Le Mans and Sebring. But with Mustangs, everyone remembers him for his work on the 350 and R Model, and for a race he ran at Green Valley, in Texas, in Februrary of ’65, the car’s competition debut.

The day produced a famous photo. The shot is as much a part of Shelby lore as any Cobra anecdote or Daytona Coupe legend. A race-prepped Mustang, wheels up, full send. For what was almost certainly the first time in public.

Chuck Cantwell: You know, Miles did the early testing in notchback cars . . . And he was a good guy to work with, he’d built cars himself . . . I don’t know if he had an engineering degree, but he was a very good car engineer anyway.

Sam Smith: It’s funny how often you see that in this business.

CC: A very pleasant guy to work with. And you know, the development, like I said, wasn’t terribly rigorous. We started with a solid platform.

SS: Shelby’s shop outgrew its first home, in Venice Beach, in early ’65. Production moved to a hangar at LAX. The Mustangs were off in the back. You get the impression they were lesser lights for a bit.

CC: When we started . . . but that didn’t last for long, because Miles went out in February, at Green Valley, and won the first race he ran. So from that point, we had respect. But for a while there, we were the poor sisters, sort of working in the corners of the shop.

Once we won a couple of races, we were considered equals, I guess. Or semi-equals.

SS: Any idea why the GT350 sticks with people? What is it that makes the car feel like so much more than it is on paper?

CC: I don’t know if I can say what that is—but I was surprised [by it], actually. I got to go to Pebble Beach [a while back] and met some very high-powered collectors. It seemed like everybody had a 350. They had Ferraris and Duesenbergs and all these other things, but they had 350s.

Everyone seemed to like them. And they’ve held their value—you know, I don’t know whether that’s surprising or not. In ’65, and the early ‘66s, they were pretty gutsy cars—you had to give up a few comforts just to drive them, but they’d perform real good.

It touched a vein with a lot of people. I just don’t know that I can explain it.

***

I have wanted an early 350 forever but never owned one; even a rusty hulk is out of the budget. I did, however, have a decent clone for a bit, a ’65 fastback tweaked and modded in Shelby fashion.

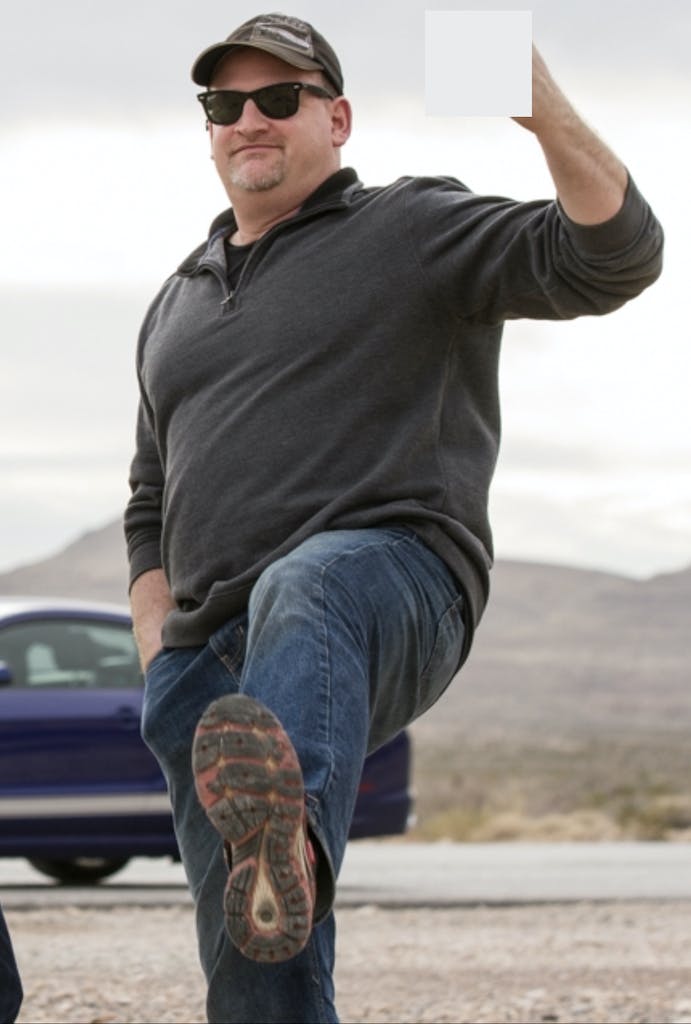

Shortly after I bought that car, I took it on a trip for a magazine story with my friend Jeff Diehl. We drove from L.A. to Las Vegas, from that Venice Beach shop and the old LAX hangar to an infamous Southern California shopping mall, ending in Shelby American’s current Vegas digs.

At the end of the second day of driving, Jeff and I split a room in some desert motel, exhausted, collapsing into a pair of beds. We stayed up, though, staring at the ceiling and talking Mustangs. Not the Shelbys, but the pull and draw of the machines they made feel better and stronger and faster by association. How the Shelby’s achievement meant so much to so many, beyond a simple racing title, an American stand in a largely European sport, and how the base car has always worked like a mirror, reflecting those who buy it.

“My cousin Ricky,” Jeff said, after a while, sighing. “Rick Pullen. Construction worker. ZZ Top starter beard. He was always a massive, strong, obnoxious human being, and a raucous, loud, obnoxious Mustang fit him perfectly. He had a Park Blue ’65 coupe with a flat-black hood. Aluminum slots. Tunnel-ram on the 289. Four-speed. Hurst T-handle. The hood scoop had a caricature of the Muppet Animal on it.”

I wondered aloud if we should just can the whole magazine story and go party with Ricky.

“It was the awesomest thing I’ve ever seen. I wanted it so bad. Roll bar. No back seat. Just two front seats, no carpet. No interior.”

I said something about turning metal into gold. And how people had just walked up to my car on that trip, over and over, with a smile: Nice Mustang.

Guess what never happens when you test a Porsche.

“You roll into a small town,” Jeff said, “you get stories. Shelby had a piece of it, but it’s something bigger. Everyone has a story. They had one or knew someone who had one or had sex in one, or they raced one or crashed one and they wanted it to be a Shelby but they couldn’t afford that so they bought a fastback or a coupe, anything, just to get close, get a piece of it.”

In the 1960s, as now, new cars were named through a murky combination of surveys, groupthink, and executive whim. Before the 350’s name was settled, Shelby canvassed his team for ideas. Mustang Gran Sport, someone suggested. Another thought they should call the car “Skunk.”

One of you probably has an uncle named Skunk. Once, maybe, he stole or borrowed some ratty old Mustang, and then he spent a whole night necking in front of the Circle K and ripping burnouts.

An everyman appeal, tied to price and badge but born of neither. A car affordable for almost anyone and yet nothing like a settling. The notion of reinvention and blank canvas, as American as steak. And that gutsy, unplannable four-letter vibe that almost everyone understands, even if they can’t put their finger on why.

When they first took it road racing? In that moneyed and high-strung crowd, with Only Two Seats? And they won?

A certain set might hear that story and wonder how it could mean so much to so many. The rest of us, well, we can’t picture a world where it couldn’t.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

As a teenager in 1966 I cherished this car. There were a few street versions running around town. I grew up not far from Road America and witnessed the magic these cars made on that track. Just sixteen years old I vowed someday I would own one. It never came to pass but the memories are as exciting as ever !

I remember the cache of them when they hit the streets. Never a Mustang guy, I wasn’t drawn to them, but I listened when others talked about how to battle them. Then I saw a few run, and the bubble burst rather quickly. The mystique was far more powerful than the actual product. Now, maybe the R Models would have produced more awe on track, but there were none of them around my town back then.

Born in the 60s – always a Mustang fan. Loved the GT350. Lucky to buy a 1970 Boss 302 in the late 70s when it was just a gas hog on a used car lot. Still have that 70 Boss 302!

Always loved the early Mustangs. My dad had a 68 that he traded for a new 69 Mach 1 ( got my 1st driver’s license in that car). My wife had a 65 when we got married ( I had a 70 Roadrunner) wish we still had both those cars. Sam – your friend Jeff Diehl – is he the one of NHRA funny car fame ( the surfer) with the beautiful wife?

The Murray Kempton of Hagerty.

A regal compliment. Although Kempton never learned to drive, he was at the top of magazine journalism. Knowing Sam, he has already thought about jumping in and telling us that he never learned to drive either. Kempton was equally self-deprecating.

In 1966 I was finishing school. I had a budget of $4,200 and wanted a sportscar. It would be my only car–a daily driver. There were several choices at the time, including the Lotus Elan, Alfa Spider, Porsche 912, Sunbeam Tiger, Volvo 1800, and the Shelby Mustang. The era was rich with cars in that class.

I found a dealer that would give me a test drive in the Shelby–a short jaunt in a local, city park. I don’t think the car had power brakes. Approaching a stoplight at a leisurely pace, I nearly panicked at the amount of strength it took to get the car to stop. To this day I still have nightmares about it–the feel of my back being pushed against the seat in a total effort against the brake pedal. I’m sure at track speeds the brakes came into their own, but, as special as it was, the car was too much of a “mission” for my purposes.

I understand Hertz fitted power brakes for their rental GT350 fleet.

Each of the cars on my list had a definite personality, and offered a unique driving experience. I chose the Elan, which led me to autocrossing, and which forced me to quickly gain mechanical skills. Much of my future was triggered by that decision. I can’t help but wonder the path my life would have taken if I had made another choice. I doubt it would have been as much fun.

Thanks for another masterpiece. I think the Secret Sauce is in the sensory output of the things, and that exercising one is a conversation with the car and the laws of physics and how the two thrust-and-parry with you. Many old/classic cars can do that, but the Shelby stories are a unique backdrop: fairly marvelous feats in period, and just about impossible in today’s world…The GT350 embodies the zeitgeist of the ’60s in the way it’s born of postwar optimism, experimentation, rule-bending, and iconic personalities, and it’s very much – perhaps emblematic of – what was once called A Man’s Car.

Sam Smith, I know you won’t agree, however you are a National Treasure.

How do you know my every automotive thought? As well as those of everyone else?

The GT350 is imprinted on me from the moment I saw the first one at Jerry Alderman Ford in Indianapolis as a teen.

If we had time, I’d tell you how I conned the sales guy into letting me drive it.

Maybe next time.

Part of the Mustang development was done on a 1963 Falcon Futura raced at Santa Barbara by Pete Corts on the Memorial Day 1964. Pete Corts went on to work for Shelby. He had great races that weekend with Mike Jones driving a Corvair entered by Bill Thomas Motors.

I love reading Shelby stories. Keep them coming.

The Mustang has always been in my heart even though I drive now a ’67 convertible C2. I had a ’65 Yellow convertible HIPO that was a sheer delight to drive and to just admire. An acquaintance when I was in Maine back in ’66 had a 350R which I thought at the time a bit too racy as it had no interior, real bucket seats, roll bar, loud exhaust coming out just under the door and a scary aluminum front end. (He always thought someone would punch a hole in it just for kicks.) Still, we had some good times being foolish with those cars and more than just a little stupid at times!

In the mid sixties in Australia, a man named Ian “Pete” Geoghehan was unbeatable in a ’67 notchback. he won four Touring Car titles in a row. Legend. Car and Man.

Great read as usual Sam, thank you

I am sitting in the pits at Laguna Seca reading this article. I am on the pit crew for a 65 Shelby GT-350.

We once were at a track day with a GT350 clone. The car allegedly featured an ex-Roush NASCAR engine. What wasn’t deniable was the fact that you could tell EXACTLY where the car was on track just by listening for it. “There he goes up the hill from 5 to 6…”

It was awesome to experience, almost like watching history but with a boneshaking soundtrack.

“There he goes up the hill from 5 to 6…” Are you, per chance, speaking about Road Atlanta? I know the sound well. I love the sound of a single car on a track even when you are standing somewhere out of sight of the car. If you have the mental map of the track – as I do of Road Atlanta and some others – it makes the hair stand up….

The photo of you and your friend at the gas station at night, with the car in the background, has haunted me ever since you first posted it on Instagram. It has an effect on me equivalent to something like a Homeric recitation of a tale of the gods. I’ll try to explain. Hang on. An anthropologist named Malinowski had my favorite definition of myth: ” . . . the rearising of primordial reality in unique form.” When I look back over my long life, I can only apply the term “primordial reality” to the year or so after I first got my driving license. The photo of you and Jeff is the rearising of my primordial reality in unique form. I do not exaggerate when I say that the high point (the early primordial point) of my life was when I was first able to cruise the streets of Jackson, MS, at night, with my best friend or by myself or even with the very occasional female, from the Billups gas station at the south end to the Billups gas station at the north end, or vice versa. I leaned against gas pumps! I never had a “hot” car, but I had “wheels.” And the possibilities were endless.

And for me, cruising back and forth between the Shoney’s in Newport News and Hampton, Virginia. No GT350s at that time as it was the rea of Hemi ‘Cudas and the like. Me and my buds in my van but in our minds it was our American Graffiti moment. Living vicariously through others. So, yes, the pic of Sam and Jeff does bring back memories. The pic is not dated but is timeless.