Media | Articles

Music For Your Road, no. 1: Some jazz records I have loved

(Please welcome former Stereophile author, classical-music producer, and audio-equipment designer John Marks in his debut column for us. John will be sharing his music and knowledge with us on a frequent basis. Most of this music can be heard via any streaming service; the most esoteric selections may require that you be a subscriber to the Qobuz HQ streaming service. Enjoy! — jb)

There’s respect. And sometimes, there’s also love. Here are some of the jazz recordings I have loved. (So, obviously, this list is both personal, and subjective.)

But first: let me make an attempt at a workable definition that may illuminate the differences between “jazz” on one hand, and popular “instrumental music” on the other.

Jazz is an American musical art form that developed out of ragtime (“ragged time”) piano, as exemplified by the music of Scott Joplin (1868-1917). During his lifetime, the “Maple Leaf Rag” (published 1899) was Joplin’s most successful composition. However, the Ragtime Revival of the 1970s achieved critical mass when Joplin’s theretofore less well-known rag “The Entertainer” was included as part of the soundtrack of the film The Sting.

Ragtime music is characterized by an uneven beat. That is, the strong rhythmic beats or accents have been relocated to where they usually would not be. Therefore, our first definitional criterion is that jazz usually has a complex, non-metronomic beat: the rhythm in jazz is “syncopated.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Secondly, jazz usually involves some degree of improvisation. That is, departing from the melody (which is often a song) as it is known to have been written; or, creating a new melody, tune, or pattern to embellish. However, in practice, there is a rather broad continuum.

Some of the most iconic jazz music was almost entirely written out, such as the big-band charts by Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn. Nevertheless, that music itself was in the spirit of improvisation, and most big-band charts left room for soloists to improvise over an allotted span of measures.

Obviously, some of the most famous jazz music was, indeed, made up on the spot. Many of the tunes on Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue started out as little more than one-line notations of a “white-key” (modal) piano scale as the basis for improvisation.

Thirdly, and although this criterion is historical, in today’s world, it might be debated: jazz music usually has some link to or resonance with African-American or Afro-Cuban culture. I think that that is valid, but only as long as “culture” is taken in a broad sense, and not a narrowly stereotypical or pejorative “Catfish Row” sense. (Catfish Row is the fictional neighborhood in which the Gershwins’ opera Porgy and Bess is set.)

To give one example of the breadth of the diversity of African-American culture, in 1944, Miles Davis entered the Juilliard School, where he familiarized himself with musical scores by then-contemporary classical composers such as Stravinsky, Alban Berg, and Prokofiev.

Of course, definitions are a product of a time and a place.

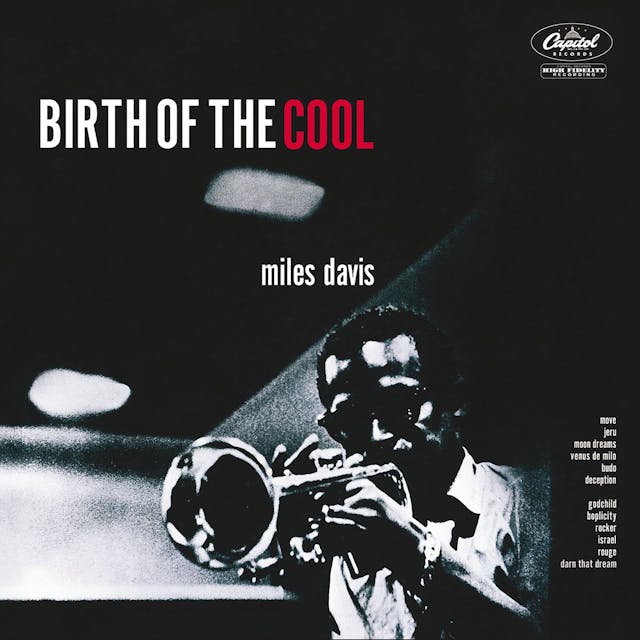

Perhaps it was over-reliance upon a rather limited, categorical definition that led to the painfully awkward result when New Yorker magazine critic Winthrop Sargeant flatly declared that, as interesting as Birth of the Cool might be, “it is not really jazz.” Whew.

From a vantage point more than 50 years removed, I think we can all agree that Winthrop Sargeant had no business telling Miles Davis and his colleagues what was, and what was not jazz. That’s because, with Birth of the Cool, they redefined the possibilities of jazz.

I have created a playlist of these 12 albums on the Qobuz streaming service—more than 12 hours of music! All the albums are available in at least CD Quality; titles with high-resolution versions are noted. To the music!

1. Miles Davis: the Birth of the Cool sessions (1949/50)

Birth of the Cool grew out of what I conceive to have been a charmingly nerdy enterprise: a basement-apartment music-theory “study group” where forward-looking young musicians would gather, earnestly to plot out the future of jazz.

It might have remained merely academic and theoretical, except that Miles Davis decided to shape them up into a performing group distinguished by its compactness (about half the size of the smaller range of “big bands”), the richness of its harmonies, and the generally slower tempos. That, indeed, was the birth of “Cool Jazz.” (Eleven sides from the original 78-rpm records were reissued together on a vinyl LP, in 1957, under the title Birth of the Cool.) (Qobuz has a hi-res version.)

2. Clifford Brown with Strings (1955)

Of all the trumpet players who came after Louis Armstrong, the one who phrased most like a singer was Clifford Brown. Following in the footsteps of alto-sax genius Charlie Parker, Brown recorded a “with strings” album in January 1955. The set list reads like a “Best of the Great American Songbook” cheat-sheet, the first four tracks being “Yesterdays,” “Laura,” “What’s New,” and “Blue Moon.” A precious moment in time, frozen in amber. If you love Kind of Blue, Sketches of Spain, or Porgy & Bess, then you already love Clifford Brown with Strings.

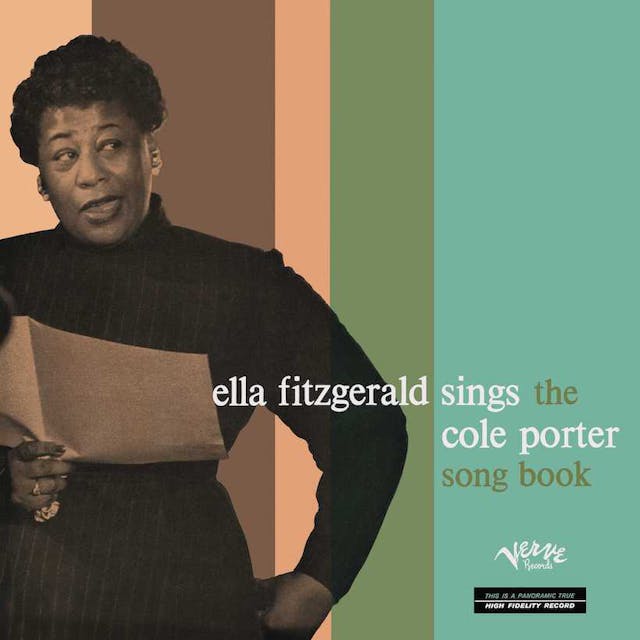

3. Ella Fitzgerald: The Cole Porter Songbook (1956)

Cole Porter was one of the most significant contributors to what is known as “The Great American Songbook.” Ella Fitzgerald’s survey, made at the peak of her powers, is one of the most important recordings (of anything) of the 20th century. BTW, there’s more at work than frosty Martinis and sly winks. “Miss Otis Regrets” is about a lynching.

Over the course of my decades as a reviewer of high-end audio equipment, after confirming that I had properly connected the right and left loudspeakers, I always made a practice of playing Ella’s “Easy to Love” from this collection. That told me in a heartbeat whether the all-important midrange was at least OK. (Qobuz has a hi-res version.)

4. Michel Legrand: Legrand Jazz (1958)

This has to be the ultimate “1950s ‘Sleeper’ Phenomenal Jazz Recording.”

The total outlier in Michel Legrand’s discography is this oft-overlooked product of three 1958 New York City 30th-Street studio sessions for Columbia. Legrand didn’t play piano and isn’t credited as a composer. Instead, the 26-year old Legrand shaped up the sessions, wrote out the charts for the 11 standards (from “A Night in Tunisia,” to “ ‘Round Midnight”), and conducted.

The earliest session is the attention magnet, in that it features Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Phil Woods, Bill Evans, and Paul Chambers. (Tracks from the three sessions are interleaved in the recording’s playing order.) But, there’s not much variability in the quality of the sessions, because Legrand’s inventive arrangements are so engaging.

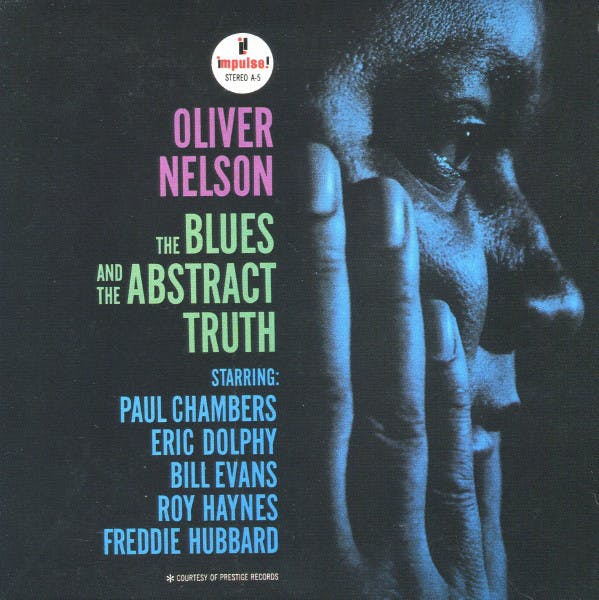

5. Oliver Nelson Sextet: The Blues and the Abstract Truth (1961)

Oliver Nelson was an alto saxophonist/composer/arranger who figuratively, and perhaps to some degree literally, struck gold on his first recording for the Impulse! label.

Nelson was extremely fortunate in his colleagues: Freddie Hubbard, trumpet; Eric Dolphy, reeds and flute; Bill Evans, piano; Paul Chambers, bass; and Roy Haynes, drums. (Evans and Chambers had previously played together on Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, in 1959.)

Baritone saxophonist George Barrow made important contributions throughout, in terms of the harmonic textures; but because he did not play any solos, he did not get billing on the LP cover.

The opening track, “Stolen Moments,” features a poignant trumpet solo by Hubbard and a flute solo by Dolphy that is all the more powerful for its being unexpected. “Stolen Moments” remains one of the most iconic Cool Jazz tracks. (Qobuz has a hi-res version.)

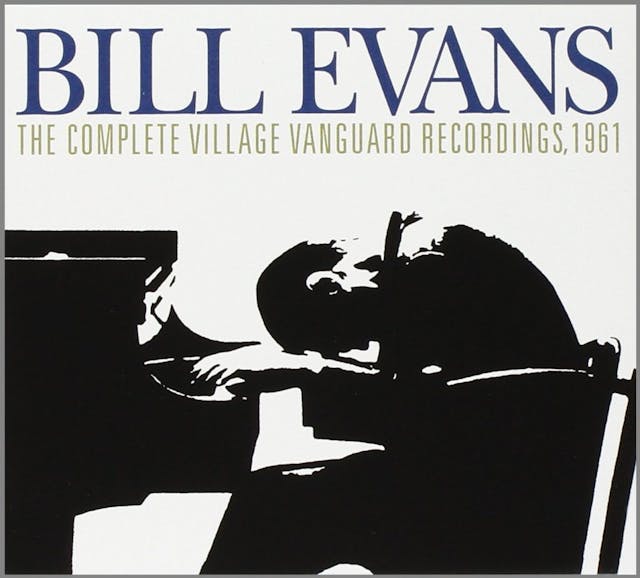

6. Bill Evans: The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings, 1961

I can’t imagine Bill Evans sitting down to play “When the Saints Go Marching In.” But, if he had, I’m confident that the result would have been postmodern, and tragic.

Evans reinvented the jazz piano trio, elevating the string bass from a rhythm instrument to a melody instrument, while relying on the drummer more to modulate the music’s intensity than to keep track of the beat. “My Foolish Heart” is one of the most beautiful recordings of anything ever made. These live recordings are of the “a precious moment in time, frozen in amber” variety.

7. Paul Desmond: Desmond Blue (1962)

In Concierto, Jim Hall’s celebrated 1975 excursion on the CTI label (see below), the master of understated guitar lyricism traded heartfelt solos with saxophonist Paul Desmond and trumpet player Chet Baker. Here’s a forerunner to Concierto, from the previous decade: Paul Desmond fronting a string section, with Jim Hall featured in a supporting role. Fortunately, Desmond and Hall managed to rise above the cash-in concept. (Gee, was there another jazz record from around that time, also with “Blue” in its title?)

I think Desmond and Hall’s music succeeds despite, rather than because of, Bob Prince’s culturally-striving string arrangements, which include such non-essentials as a mock-Elizabethan introduction to “My Funny Valentine.”

8. Stan Getz & Charlie Byrd: Jazz Samba (1962)

Creed Taylor earned a psychology degree from Duke University in 1951. I find that rather amusing, because, over the years, I have several times stated that being a record producer is nothing other than the unlicensed practice of psychotherapy. (It also helps to be lucky.) Taylor must have been good at both disciplines. He signed John Coltrane to Impulse! records, but soon thereafter, left to join the new label Verve.

American guitarist Charlie Byrd made a U.S. State-Department-sponsored tour of Latin America, and came back with a satchelful of Bossa-Nova music from his visit to Brazil. Byrd phoned Creed Taylor. Taylor thought the music would be a good fit for Stan Getz, and set up a recording session that really should take the Grand Prize for “Return on Investment.”

Recorded in a church auditorium in Washington DC, with most of the songs completed in one take, Jazz Samba remains the only jazz record to have topped the Billboard “Pop” chart. Jazz Samba sold half a million copies within 18 months, putting Bossa Nova music on the map in North America just before the lads from Liverpool knocked all the pieces off the chessboard. (Qobuz has a hi-res version.)

9. Hubert Laws: The Rite of Spring (1971)

Creed Taylor, buoyed by success, left Verve to found Creed Taylor, Inc. (CTI), the record label that “moldy fig” jazz fans love to hate. Yeah, Taylor did pay Eumir Deodato to record a “jazz” version of “Theme from 2001: A Space Odyssey.” (Well, it won a Grammy, did it not?)

But Taylor also made quite a few albums of lasting artistic value, and this brief sojourn by flautist Hubert Laws is one of them. (Ignore the naysayers.) This album is famous for its title track, but you must hear Laws’ take on Fauré’s “Pavane,” with Gene Bertoncini’s classical guitar so wonderfully recorded. The Bach Brandenburg Concerto excerpts, with some of NYC’s finest session players, strike me as quite true to Bach’s intentions. Merely updated in execution.

10. Jim Hall: Concierto (1975)

Without doubt, the greatest achievement of Taylor’s CTI label was Jim Hall’s mesmerizing reconsideration of the slow movement of Joaquín Rodrigo’s famous classical-guitar concerto. As far as I know, this is the only studio session where Paul Desmond and Chet Baker played together. The other supporting players—Steve Gadd, Ron Carter, and Roland Hanna—create such an elegant (but totally engaged and engaging) soundworld.

11. Tommy Flanagan: Lady Be Good… for Ella (1994)

Tommy Flanagan was Ella Fitzgerald’s music director for more than 10 years. Before that, he participated in such iconic recordings as John Coltrane’s Giant Steps (1960) and Wes Montgomery’s The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery (1960). One of the peak experiences of my life was to serve glasses of champagne to Tommy Flanagan and Max Roach at a little party I threw at the Waldorf-Astoria, back in the 1990s.

This trio outing has to rank among Flanagan’s best work (and this was a man with 200 album credits, and 30 albums in his own name). The opening track has a very cute intro: “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” transitioning to, “Lady Be Good.” You can hear (and feel) the love.

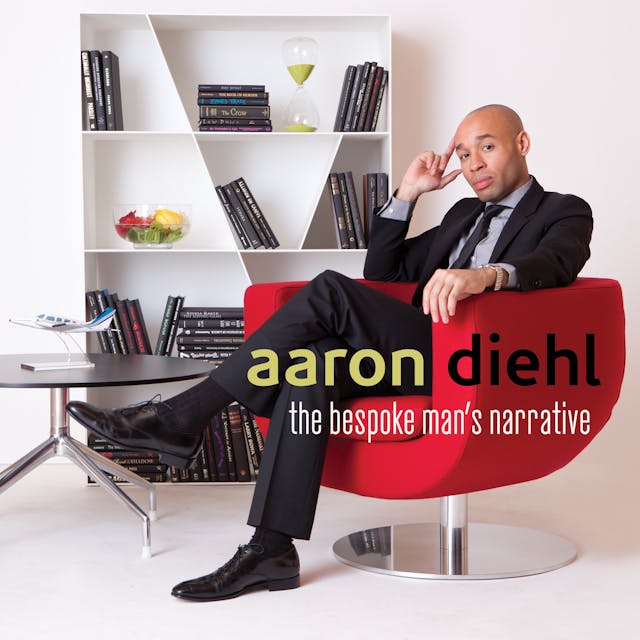

12: Aaron Diehl: The Bespoke Man’s Narrative (2013)

Aaron Diehl (b. 1985) is an astonishing talent. When soon-to-be-departing New York Philharmonic Music Director Alan Gilbert was putting together his final season, his choice of a soloist for the orchestra’s opening-night gala was Aaron Diehl, to play Gershwin.

This is Diehl’s first studio recording (his previous releases were live recordings). The quartet consists of piano, vibes, bass, and drums. Diehl’s playing in his own arrangement of the “Forlane” from Ravel’s Le tombeau de Couperin is nothing short of amazing. Also, the quartet’s “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” is for the ages. Not to be missed.

Qobuz streaming has a 30-day free-trial offer. The URL for this playlist is here.