Media | Articles

The curious case of the Sno-Runner “carburetor”

Book-smart is one thing. We can all sit in a warm spot and read any of the innumerable books that outline theory on automotive repair, including every service manual ever printed, and still not be very helpful when it comes time to pick up the tools and get work done.

Most engine tune-up items are easy targets for this kind of armchair diagnosis. It’s easy to say “just replace the points” or “give the carb a good cleaning” from the comfort of your La-Z-Boy, but in reality, those tasks are only simple if you have at least some practical experience. That experience is also called institutional knowledge and it can sometimes create an overconfidence that needs to be checked.

This realization came across my mind recently when a “carburetor” project entered my garage that I was confident I could address quickly and easily, until the part was staring back at me from a perch on my motorcycle lift.

After rebuilding seemingly innumerable numbers of the small carburetors found on mopeds, scooters, motorcycles, and any manner of yard implements, I rarely do any research before diving into a carburetor rebuild job these days. The real-world experience of having done it so many times outweighs the time I could spend reading a manual on the specific job at hand. Only rarely does this confidence bite me.

When I went to work on this Chrysler Sno-Runner, it did.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The Sno-Runner is an odd machine for a variety of reasons, with the main one being its origins. The late 1970s was not a pretty time for Chrysler, which desperately attempted to produce any product that could make it money. Someone in a boardroom saw all kinds of pitches and at the end of the day, with an exasperated sigh, declared: “The snow-bike thing. Build that.”

The result was the Sno-Runner. A one-person snow machine that packs a single-cylinder engine yoinked from the chainsaw assembly line of West Bend, which Chrysler had purchased in the 1960s.

Originally destined for saw use, the 134-cc, two-stroke engine put out 8 horsepower. Later in the production run, changes boosted the power output closer to 11 hp.

The second was the version that landed in the back of my van after a friend called me saying he bought the Sno-Runner off Facebook Marketplace because he thought it was cool. Of course, it started right up for the seller, but once the friend got it home, it wouldn’t run. He put in a new spark plug and tried starting fluid once or twice before deciding he was in over his head and that help needed to be called. Of course, I answered.

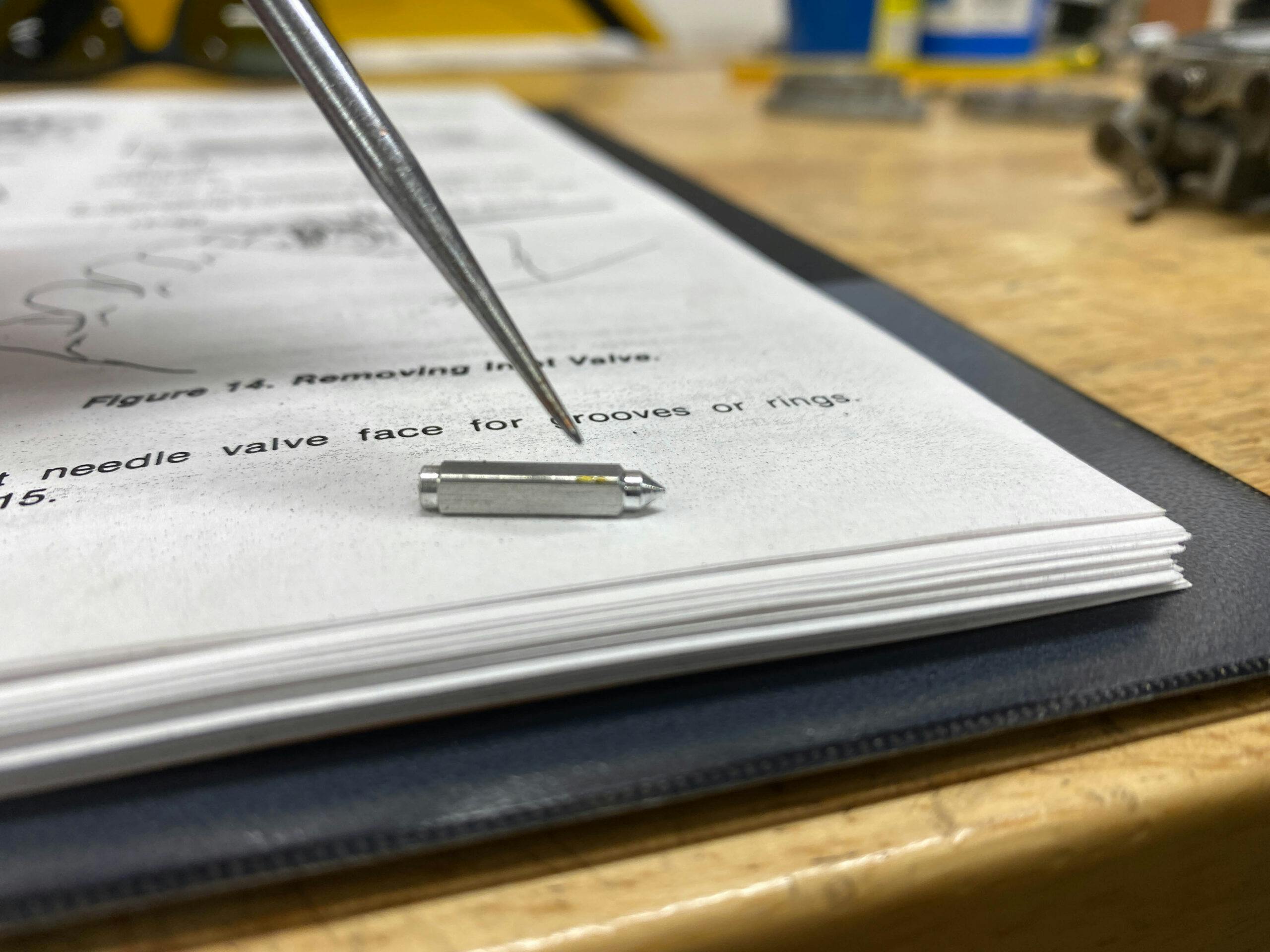

Confidently, at that. I brought the orange tube-framed machine back to my shop to make the work a little easier, but I told the friend the job wasn’t a big deal. Probably just some dried-up gunk in the carburetor after the machine had been left to sit for the summer. Take the engine apart, clean a few things, put it back together, maybe 45 minutes of work. The friend had the Sno-Runner’s service manual, but I wasn’t any too worried about needing it. A small engine with a carb—how hard could any fix be?

That’s when I noticed the fact that the sloping tube frame was also the gas tank.

That seemingly random observation lit off alarm bells in my head. That meant fuel wasn’t gravity-fed. This little engine had a fuel pump? That seemed absurd. But it had to.

Where would the pump go? How would it work?

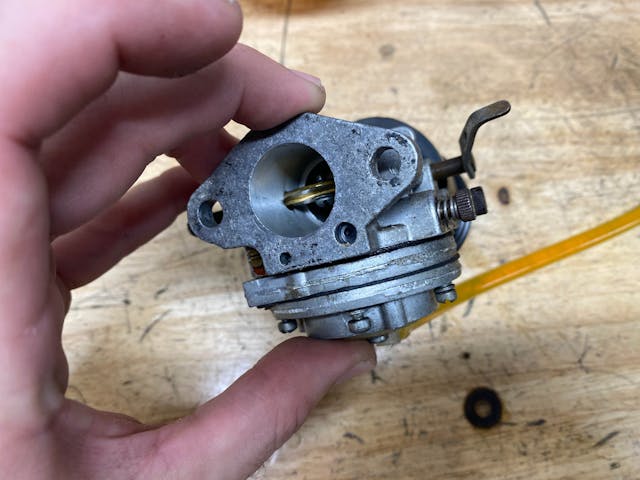

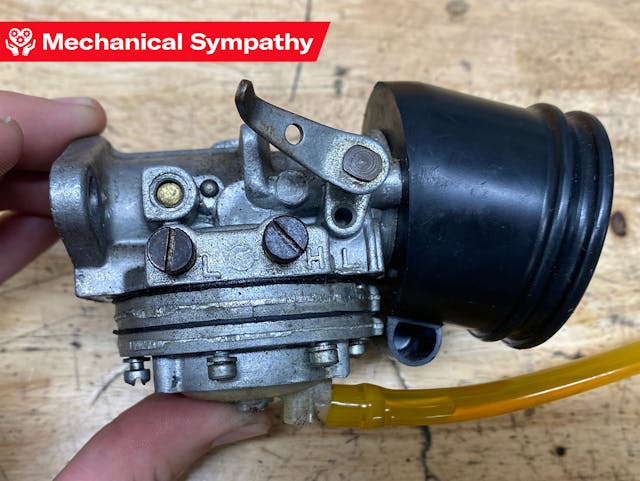

The answer is that a Sno-Runner has a fuel pump and a carb—combined. The fuel pump is part of the carb. Or the carb is part of the fuel pump? Whichever way you want to say it, the Tillotson 820A serves as both but I didn’t find that out until I stared at the “bike” for a while before retreating to the safety of the service manual to do some book learning.

The Tillotson name meant something to me, but only from the Model A Ford community. Many Model A owners happily ditch Tillotson carburetors in favor of the often better Zenith ones. Maybe this little engine was suffering the terrible Tillotson clog that affects Model As. The issue stems from the small horizontal passage in the bottom of the carb, which can get clogged so badly that it has to be drilled out.

The diagrams told me that wasn’t the case. The “carburetor” is mounted on the engine case and lacks a float bowl and the myriad of passageways typical to an apparatus tasked with metering and mixing air and fuel as they enter the intake of an engine. Instead, there was a pancake clamped to the bottom of the intake throat, which was throttled only by a single brass plate. The arrangement really didn’t make much sense—until I read the manual’s description of the carb’s vacuum ports.

This is a vacuum-operated fuel pump that pushes fuel directly into the engine.

What a wild thing. The reciprocating motion of the piston causes the crankcase volume to expand and contract, creating a pressure swing that can be leveraged to do work for the engine. In the same way that a turbocharger uses the pressure pulses of exhaust gasses leaving the cylinder heads to spool its turbine, this Tillotson uses the cycling of vacuum and pressure in the two-stroke engine to operate a diaphragm in that bolted-on pancake, which pumps pre-mix up from the sloping tank.

It was all so clear once I realized this engine was designed for saw usage, which all but guaranteed it had to run in off-camber situations or, generally, when the gas tank was not located directly above the intake.

The diaphragm pulls fuel from the lowest point of the tank thanks to a hose, which is capped with a screened pickup, to make sure it stays submerged in any sloshing fuel. The hose exits the tank with a dry-break fitting that looks a lot like a basic air-line disconnect.

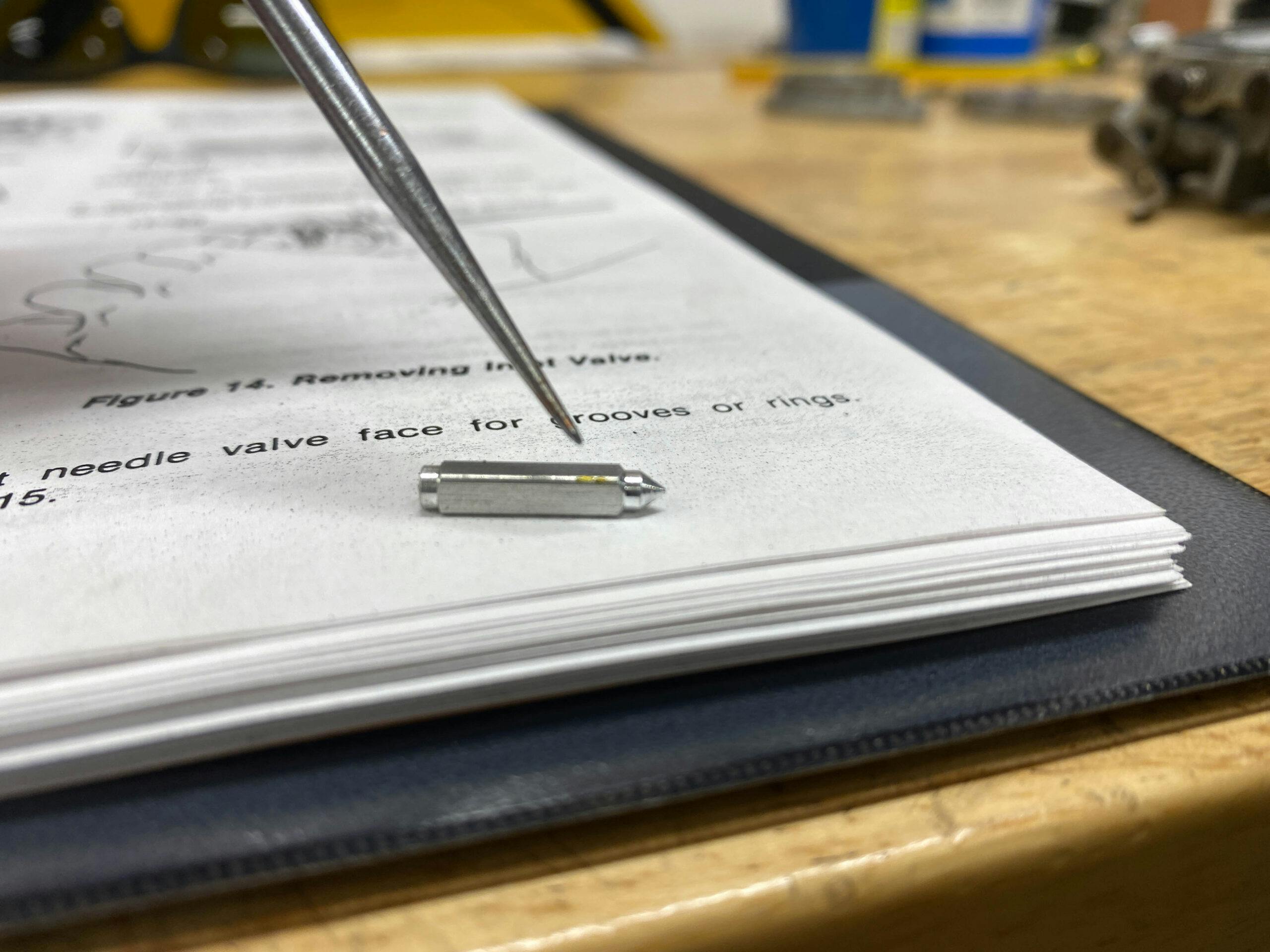

From that connection, the hose runs straight to the fuel side of that vacuum diaphragm before pushing fuel past a simple needle and seat and, as fuel enters the crankcase, into the airflow. A small bit of schmoo had trapped the needle in place and was preventing the fuel from pumping into the engine. A little spritz of aerosol carb cleaner and careful reassembly led to the engine springing right to life after a few pulls on the starting cord primed the pump and got the fuel flowing.

Could I have figured out this “carburetor” based on instinct from previous experience? Probably, but fixing it would have taken a lot longer and likely led to me doing at least one thing wrong and having to deal with the repercussions. That confidence, which usually allows us to dig into projects in a fun and effective way, stopped being a safety blanket and instead became a trap of my own making. Who would have thought that experience and confidence could be dangerous things?

I fall into ruts all the time with my garage projects. The rut comes from a desire to feel productive, successful. There are many parts of life where getting anything done requires real work and time investment. In the garage, the institutional knowledge I carry becomes my safety blanket and often keeps me doing the same handful of projects time and time again. The fact I have a veritable fleet of the same generation of Honda XR250R motorcycles built up in different forms should tell you something. It’s a shortcut to being able to pop out into the garage and take on a project with which I know I will be successful. That search for comfort projects stunts growth.

It was blind confidence that brought the Sno-Runner into my shop, but dropping that pride allowed me to leave in better shape than when I received it. That institutional knowledge might not be so dangerous after all—at least, so long as we don’t blindly follow it into ignorance.

I would have never learned about this odd mixture of fuel pump and carburetor if I didn’t step back and put the tools down to pick up the shop manual. Humility is as important as confidence in the garage. Of all the knowledge to be gleaned from a 1970s Chrysler product, I sure didn’t think it would be that.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Vacuum operated diaphragm pump carburetors have been common on engines up to and sometimes exceeding 40hp in the smaller equipment construction world for a long time. Very common in dual fuel gasoline and propane apps too. I’d look for a pinhole in the diaphragm, gaskets being replaced by silicone and general dirty operating conditions long before a crankshaft seal as the cause of a no start condition.

Tillotson & Walbro carbs have been around for a long time….most early Snowmobiles had them, Harley used some, most chainsaws…Mcculouch, Homelite, Tecumseh (Power Products), they all worked on crankcase impulse…..had a metering diaphragm, fuel pump diaphragm. Author states first one he had seen, the mature crowd myself included worked on hundreds of those carbs

Yes, I am 8 months late with this post. Kyle I have to assume that you never fiddled with go-karts, at least not McCulloch or West Bend powered ones. The instant I saw the photo of the carb, I knew it was a Tillotson carb. Back in the 60’s and 70’s, I ran Mac powered karts a lot. The diaphragms would often dry out over the winter, so I would replace the main diaphragm and the fuel pump diaphragm. And the Mac carbs were more like fuel injection, the later carbs didn’t even have a venturi, since the main diaphragm would inject the fuel directly into the airstream. Glad you got it fixed!

Those carts and engines were already collectors items by the time I was born so not something I have any experience with. Was fun learning on this one and surprised this style of carb is not really used any more. The flat gaskets seem easier to produce than most standard carb parts, but maybe it’s economy of scale taking over.