Media | Articles

Does My Project Need More Time or More Money? If Only It Were Simple

Two weeks ago, sitting on the couch enjoying the tremendous warmth of a late-season fire in the wood stove, I found myself annoyed. On my knees was a laptop, the browser open to eBay, cursor poised over the “complete purchase” button. Its delightful blue color just invited the light tap of an index finger. That finger was making a quick scroll of my bank’s app, which displayed payment due dates in bold and account balances with a discouraging lack of commas. “Complete purchase” would have to wait. I closed the laptop, locked the phone, and left both on the couch while I walked into the garage to stare at something that might bring some joy rather than frustration. It didn’t really work.

So often a project only moves forward with investment: In the world of old cars, either time or money. Many projects require both, though the slider can be moved to and fro between them to balance the requirements of calendar, budget, or skill.

While working overtime in the Hagerty call center a few years ago, I asked a friend why he was picking up extra shifts; it wasn’t regular behavior for him. He outlined that he wanted new flooring in his bathroom, and when he had priced it out, he realized he could make about the same amount of money in eight hours of OT, taking insurance renewal payments, as it would cost him to pay a pro to install the floor. Why should he learn to do a job he’s never done, and get a result to match, when he could do something he is good at and buy a professional-grade result? The interaction shook a little something in me about the perception of value.

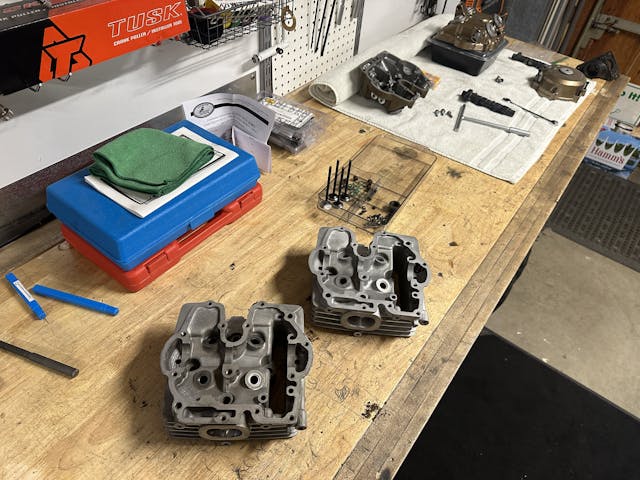

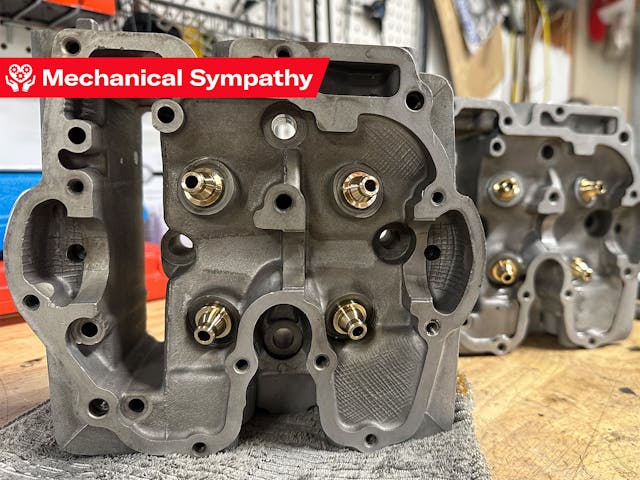

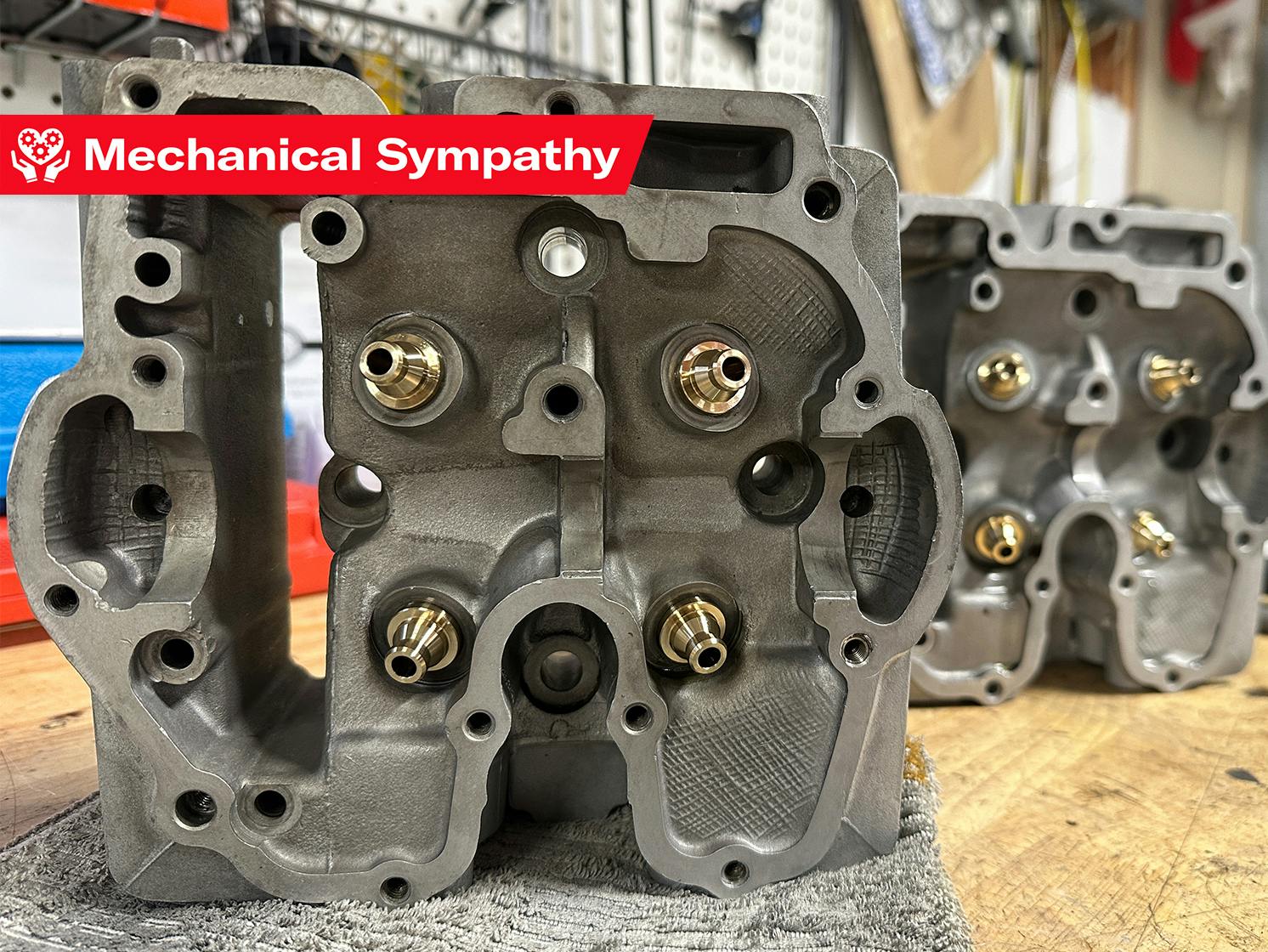

Sitting on my workbench are two bare Honda XR250R cylinder heads. Both represent the last steps in a pair of engine builds that have been stretching on for about a year now. A few months ago, the people at my local machine shop let me know they were starting to wind down their work on smaller engines. The setup time wasn’t paying enough anymore, and, rather than charge customers crazy amounts to make the work worthwhile, the shop had decided to focus on more profitable projects, many of which were already keeping its staff busy. I don’t blame them.

Into the receipt pile I went on an archeological dig to find the paperwork for the last cylinder head I had done. It was for the Six Ways to Sunday project, and that engine has been rock-solid. I could mail off this pair of heads to the same shop that rebuilt the one for Six Ways, but that one had also needed a fair amount of TIG welding and CNC work to re-shape a combustion chamber that had been battered by a broken valve: a four-digit bill when all was said and done. Worth it, but these two cylinder heads don’t need such major work. I could get away with pressing out and replacing the guides, reaming them to size, installing valves, cutting seats, and putting in new springs. A couple of those tasks are advanced DIY, but the entire process is outlined step by step in the factory service manual. After finding an affordable option for seat cutting (more on that later), all I had to do was ream the valve guides to size. It couldn’t be that hard to make round holes that were the proper diameter, could it?

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

High-speed steel and even carbide reamers can be purchased easily. There are even versions specific to valve-guide reaming that have nice, long cutting flutes and a generous pilot area ground on the lead-in to ensure the reamer is started straight down the bore. A flurry of packages arrived at my house, adding a dozen lines to my to-do list. Each step required me to use a new tool, from driving out the valve guides to reaming the guides to fit the valve stems. I know those two steps are next to each other and not the entire process, but that’s as far as I got.

In the attempt to ream the valve guides, I learned my first lesson: Material matters. This high-speed steel cutter made it about halfway through the first guide and then bound up. The bath of cutting oil couldn’t keep the abrasive relationship from heating up and the C630 bronze reached out and took hold of the steel by the collar. I had prepared to machine bronze guides. I had failed to prepare to machine nickel-aluminum bronze guides.

We don’t know what we don’t know—and it’s impossible to know everything—but when choosing to slide the knob towards DIY rather than pay-a-pro, we have to somehow get ourselves to roughly the same skill level as the pro, at least in a few specific aspects. That takes time investment. I thought I could be cheap on both fronts by not investing the time to do proper research, which would have led me to purchase a diamond hone or different guides, and also by not investing the money to pay the pros. I thought I could get by with a little luck.

The slider between investing time vs. money doesn’t always move in a straight line. It instead slides on a rollercoaster manipulated by a multitude of factors from weather to workspace to tooling. Each job is its own rollercoaster; some are relatively gentle wood coasters, and others require tolerance for very rapid changes in direction. Reading the measurements of a roller coaster cannot tell you what the experience will be from the seat.

I haven’t even got to the exciting part of my cylinder head work, and I’m a little nervous. That’s probably a good thing, though. Learning often requires bumping up against our own ignorance in some way, shape, or form. I got cocky with my skills and the job checked me. Now my to-do list includes a a trip to the machine shop.

While I love the idea of purchasing a rigid hone and adding some seriously cool capability to my garage, the four-digit price tag would take a long time to pay me back. Instead I’ll be swallowing my pride and dropping by the machine shop with the hope of bribing them to ream the valve guides to size for me. I still plan to do the valve seats at home, so this rollercoaster ride isn’t over yet. The first drop might have spooked me, but the allure of the upcoming twists, turns, and potential loops are why we get in and lock down the proverbial lap bar. There is a certain fun in experiencing a familiar thrill, but there is also the intoxicating feeling of doing something new and figuring out that it really isn’t that big of a deal—or, maybe, that it is.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Silly question, IMO – EVERY project needs BOTH more time AND more money!

DUB6, you certainly got that right! My personal experiences have led me to always hope for the best but expect the worst!

I thought the answer was yes to the question.

Sometimes it’s not worth your time, you pay somebody else to spend the time on it.

Like the old saying, “Speed costs money, how fast can you afford to go?”.

Cubic dollars.

There may be a proper name for it, but the time vs money equation always seems to prioritize whichever’s in shortest supply, doesn’t it ? And there are times indeed where the checkbook is one’s best tool for a job. There’s a reason behind the term “lost art”…years of hard experience to develop real expertise, and more than I possess.

“Does My Project Need More Time or More Money?” Yes.

I thought “Time” was “Money”. Or is it the other way around?

Yeah, try paying your vintage parts dealer’s bill by offering him some of your time – see how far you get with that! 😁

My opinion is if the special tooling you’d need for a new operation costs the same or even a little more than the pro’s estimate, buy the tool. The internet will show you how to use it. More than once I’ve paid reputable shops to botch my job. If the tool can be bought used you might get your money back (or more!) by flipping it when you’re done if you don’t ever expect to use it again. When shopping: cutting tools should almost always be purchased new. Never fall for “Drawer full of endmills, barely used!”

Truths from Tinkerah! 😁

As I recall, opportunity cost is when you do what you’re good at and pay somebody to do what they’re good at

Cheap ain’t cool!

Cool ain’t cheap!!!

Time, inclination, energy and money are prerequisites to any major project, only the ratios change.

Sometimes learning a new skill is the only way, as it becomes harder to find professionals willing to work on older vehicles. The great feeling of accomplishment that comes with eventual success certainly doesn’t hurt and helps compensate for the anguish that accompanies expensive screw-ups along the learning curve.

A corollary to this is the question of buy special tool vs. use non-special tool/break something expensive/hurt yourself route. A good example is a manufacturer’s special spring compressor vs. a crappy generic Autozone special. More and more lately, I buy the factory tool. Or I hire a pro. Both are cheaper.

Love your writing, Kyle!