Media | Articles

In the Moment: Of wagons and losses

Welcome to a regular feature we call In the Moment!

A while back, Hagerty’s editor-at-large, Sam Smith, began kicking off our mornings by plopping a random archive photo into our staff chat room. His descriptions of those photos were fun, so we began running them as irregular columns.

These days, Sam writes ITMs specifically for publication. Often while drinking too much coffee and going rhetorical walkabout. Enjoy, and let us know what you think in the comments! —Ed.

***

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The Volvo 850 estate,” he said, was “ . . . the largest car in the series.”

That’s Rickard Rydell, a Swede, a Volvo factory touring-car driver from 1994 to 1998. The line is the kind of dry, accurate statement often seen in carmaker press releases. Naturally, a press release is where I found it.

That release was issued nine years ago, on the 20th anniversary of the arrival of the Volvo 850 wagon in the British Touring Car Championship.

A racing wagon!

A Volvo!

How unlikely and marvelous!

Witness, once more, the unlikely marvelous!

This column often zooms in on historic photos for reasons of emphasis or detail. We should zoom in.

What’s that, you say? Just some racey wagon? Why the hubbub?

You say you don’t . . . want . . . to zoom in?

Would a taste help? A photographic amuse-bouche?

Or maybe this one?

Still no?

No matter. I run this page, see? We shall zoom again soon! If you don’t understand why, feel free to click the window closed and look at something else. Anything. Five facts about ponies. The Mustard video on Ekranoplans. This brake caliper I just bought for my 200,000-mile German daily driver, a component that, while reasonably priced, made me sigh and remember how much I miss my old Chevy K1500 pickup.

Not least because reman pad-grabbers for that old horse were a whopping $19.95 from RockAuto, absent that site’s mandatory five-dollar core and infamous $400-per-pound shipping.

Did the boring folks leave? Good.

Those of you that remain presumably do so for one of three reasons:

1. You are genuinely curious about that racing wagon

2. The stream-of-consciousness writing style deployed in these columns hits something like a car crash, and you’re unable to look away

3. WHEELS UP, YOU SONSAMONKEYS, HERE’S THAT SWEET-HOT ZOOM!

(Please continue reading, and do not leave for facts about ponies. We apologize for Sam. We’ve asked him to stop this kind of thing, but he won’t. —Ed.)

Forgive the dramatics. Volvos can evoke strong emotion, flying Volvos moreso.

At the risk of stating the obvious, we are each built of our history. When I was in high school, in the late 1990s, I had two friends with Volvo 740s. Then as now, those cars were not particularly desirable, merely old and cheap.

Like the BMW E23 7-series or the Volkswagen Phaeton, the 740 seems destined to live in the shadow of its smaller siblings. The E23 is perpetually overshadowed by the contemporary 3-series, the E30; Phaetons are generally ignored in favor of the VW Golf. When it comes to Volvos, most people prefer the smaller and less cushy 240 models.

This makes sense. The 240 was built from 1974 to 1993, yet its quirk seems timeless. The model offered the looks and performance of an armored train. It drove like a Detroit muscle car, if a Detroit muscle car were both wholly devoid of muscle and designed by a people genetically hardened over thousands of years of nine-month winters.

The 700-series Volvos, 1982 to 1992, handled better and could be had with more power, but they were very much of their period, styled like angle iron through a wood chipper.

Wait, that’s cruel.

Maybe . . . an Aston Lagonda through a wood chipper.

Regardless, they are fine cars, and some people like them. One of those high-school 740 owners was my friend Seth Teel. During our junior and senior years, he drove a red 740 wagon, a high-mileage automatic. The other friend, Matt Williams, drove a similarly weathered 740 Turbo sedan.

Matt’s car didn’t stick in memory. I mostly remember how its small factory boost gauge sat off in a corner of the instrument cluster like an afterthought. The car’s analog dash clock, parked next to the speedometer, was maybe four times as large.

That choice is very Volvo, very Swedish: “You have boost, but who cares? Shouldn’t the clock be larger? For are we not all born of the opportune meeting of the great and yawning worlds of Niflheim and Muspell, their fated intersection at the featureless void of Ginnungagap? Do we each not count the days until our inevitable reunion with Odin the All-Father—son of Buri, Bor, and Bestla, who were in turn freed from the eternal ice by the slow but persistent licking of the cow called Audhumla? Isn’t time all there is?”

Side note: Do not go down the rabbit hole of Norse creation mythology without time on your hands. It’s incredible.

***

Back to Seth Teel’s car.

Seth is like a brother to me. This individual long ago became one of my top-five desert-island humans, the kind of person you collect almost without thinking, then later wonder how you managed without. Like my wife, he knows me better than I know myself.

More to the point, when I was an angry high-school kid, insistent on being alone and stupid about far too much, Seth decided, in the face of my own great protest, to be my friend.

Because I clearly needed help.

We met in some class at school, junior year, discussed shared interest in some band or record label. High school being high school, I had recently been abandoned by a few old friends, or so I thought. In retrospect—this realization did not come for years—I had simply grown sad for a bit, as teenagers do.

Perhaps it was loneliness or hormones. Whatever the reason, that sadness caused me to stop calling that group of old friends. When we did chance to hang out, I no longer knew how to be myself. I could only be grouchy and miserable, a terrible combination of far too sensitive and not sensitive enough. Which, in turn, prompted those people to stop calling me.

That “abandonment” was a minor thing, but it set to motion a larger process, one I have never really understood.

In the weeks that followed, I grew angry and despondent. Affected depression, tried on like a hat, opened the door for real depression, complete with physical symptoms. When my parents, firm but patient people, tried to help, I responded to their outreach and love in predictable fashion: I became a tremendous dick.

The selfishness and self-sabotage snowballed. I went to my part-time job religiously but started cutting school regularly. I began sleeping through classes and spending months of weekends in my room. I begged out of family meals, laying on the floor next to my bed and listening to music for hours, pausing late-night staring contests with the ceiling only to slouch to the kitchen, where I would offset a lack of dinner by cooking and eating half a box of instant mashed potatoes.

Nights were awash in self-pity. Hours where I angrily read books or sullenly watched TV while wishing for plans and friends just so I could cancel on each and show everybody. (Show them what? Who knows.)

Perhaps the most asinine part was my opinion about new people. I became convinced that any potential friend or girlfriend who reached out at school—and they did, remarkably—was insincere. Engaged in some long con to make fun of me. No evidence existed to support this theory; I conjured it from thin air. I hated myself and couldn’t let it go, I thought, so why would anyone else feel different?

It seems so stupid now. But then, we all are, growing up.

Seth had our address; he had once visited the house to pick up a loaned CD. In the weeks after, he must have noticed something in class, because he just kept showing up at our front door, uninvited. Not that there weren’t other outlets. He was tall and funny and in a band. Girls were drawn to him. Still, there he was, afternoons, Friday nights, whenever, on our stoop, ringing the doorbell.

That was, I would learn, Seth. When he sees something he doesn’t understand, he shakes his head and dives in. So he would come to our front door and tell my parents he was here to see me. When I responded by moping around the kitchen or grumbling back to my room to sleep, he would invent some reason to stay, then trap my mom in polite conversation both absurdly polite and peppered with F-bombs. (She found this combination hilarious and endearing, but then, that was my mother.)

Mom died a while back, but as she once jokingly told me, Seth was the son she never had. That affection locked, I think, when he began pulling me out of the house.

Naturally, I resisted. Not least because I wasn’t sure why he was there. Early on, when I refused to leave, Seth would simply plop down at our kitchen table and kick off long chats with my parents. Or he’d do things like amble into the den and throw a movie on the TV while simultaneously ordering a pizza and talking to the dog. Either way, he hung around for hours, infinitely agreeable and chipper but somehow immune to argument. He shrugged it all off, as if it was just how the world worked.

One day, worn down, I caved and we left. I want to tell you that he physically threw me into that Volvo and shut the door in my face, but I’m probably making that up. And while time has blurred that first destination, it doesn’t matter, because none of them did. Bomb back roads for hours? Drive clear across town to see some tenth-rate punk band in a nearly empty hall? Pinball at midnight? Hit a party at some horse farm where teenagers were definitely not drinking bathtub ‘shine from an actual bathtub? Sure, yeah, why not?

If it sounds like a movie, it wasn’t. It was mostly just driving around, looking for something to do. The space between spaces of any high-school life. But it helped.

Somewhere along the line, we became friends. The process was so mysterious for my parents that Mom eventually sat Seth down and asked if we were gay. (Not judgmental; that wasn’t her. More like, What’s going on? Can I help?)

When you’re young, some people simply teach you to be yourself, and without trying. Mostly by encouraging you to be okay with what you see in the mirror. Because they’re okay with it.

Like me, Seth is now in his 40s. We see each other about a week each year. Even now, I can’t hear his voice without picturing that tatty old Volvo. He lives in San Antonio, where he remodels old houses for a living and wears flip-flops every day. He is as complex as anyone and has not had an easy life, but he is still the same guy, the one who kept showing up. Only now he pours weapons-grade cocktails and rattles off double entendres while my kids climb him like a jungle gym. The kind of behavior that would have made my mother laugh, then roll her eyes, then move to refill his drink.

Digression for another lodestone: One of my favorite Seth Teel stories involves how, senior year, he totally did not start a side business selling psychedelic mushrooms, which are definitely illegal and should never be eaten by anybody.

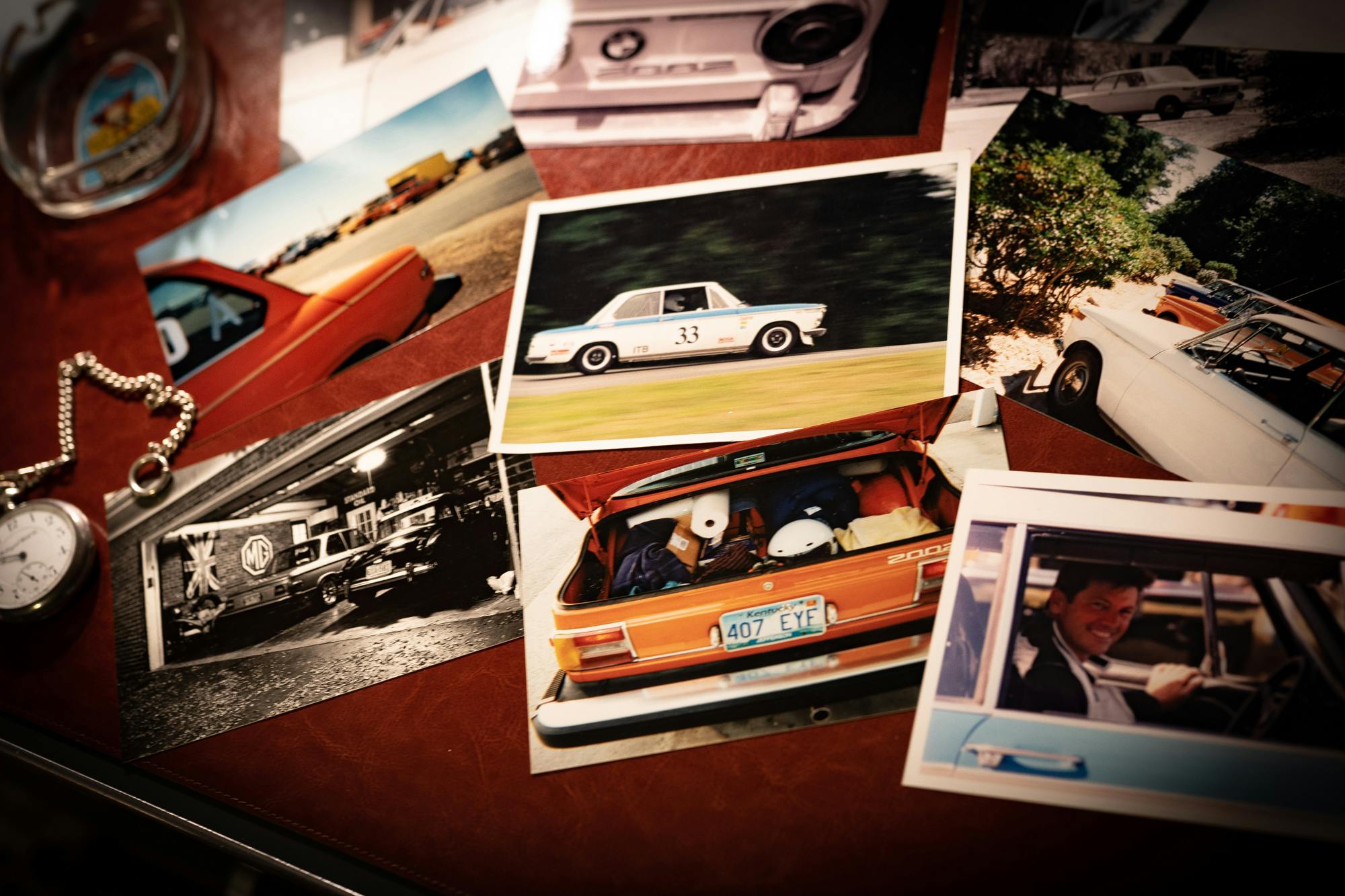

Had this concentrated dose of not-capitalism actually happened, it certainly would not have lasted months. Around the same time, when an unrelated venture caused several thousand dollars to fall into his lap, Seth used that cash to buy a white 1969 BMW 2002. No great thought there; I had an orange ’76 2002 at the time, and he liked it.

Seth’s Volvo and the orange car are long gone, but the white one is still around. Years later, when I had returned to something like my normal social idiocy, Seth sold the BMW to my long-suffering, good-natured father. Then, partly because 2002s loom large in my family, Dad and I converted it to a race car. We went road racing, in a cheap entry class, with the Sports Car Club of America.

We didn’t know much, and we weren’t very good. I’m better now, though not as much as I’d like. Still, the experience remains one of the best parts of my life.

But that’s a story for another time.

***

You ever get the feeling that an inanimate object is somehow aware of your wants or needs?

It’s not like the timing lines up. That curb-hopping Volvo photo is from 1995, the year I turned 14. At that point, I wanted nothing more from life than to watch Monty Python movies while listening to loud music and thinking about girls and cars.

I was a happy dork and didn’t care why. A few years later, I couldn’t stop thinking about myself.

If anyone ever tells you that being a teenager feels normal, they are lying.

“Touring Car” is British English for a family vehicle with four seats. Predictably, the British Touring Car Championship has long focused on four-door sedans. Established in 1958, the series has hinged on fierce and close racing, to say nothing of a certain image.

Professional athletes are in many ways professional complainers, and racing drivers are no exception. When the Volvo appeared, the competition grew whiny. Other manufacturers protested—the car’s presence diminished the sporting nature of the championship, they said.

By the 1990s, Volvo had a solid reputation for slow, safe, and dependable cars. The 850—a five-cylinder, front-drive sedan—was attempt to change that. Launched in 1991, the model was designed to replace the aging 240 range but ended up straddling the line between it and the marque’s larger 900-series cars. Which were really just a light redesign of the 700s, machines like Seth’s 740.

I have countless miles and years in Volvos. My grandmother drove a 240 wagon, then a 740 wagon; two more 240s filtered through our immediate family. Then, in 1995, Mom bought a new 850, a black manual sedan. That car was clearly related to older Volvos but of different cloth, more nimble and lively. (A mechanic friend once jokingly called the 850 “an Audi 5000 that works,” and he was right.)

The day Mom took delivery, I poked around the showroom a bit. A BTCC poster hung high on a nearby wall.

I stood there, gazing into that livery, thinking, Oh? Yes?

Volvo took the 850 road racing as a marketing exercise. Why the company initially chose the wagon for that work, and not the sedan, is one of those bits of history that much of the internet gets lightly but critically wrong.

The factory team was run by Tom Walkinshaw Racing, the British outfit behind Jaguar’s 1988 and 1990 Le Mans wins. A quick internet search will suggest that TWR ran the long-roofs for aerodynamic reasons. Next to an 850 sedan, the wagon offered drag and downforce benefits, but the advantage was minimal. In reality, the Swedes made the call to suck up media attention, and the gamble worked. In that first year in the BTCC, the 850s never finished higher than fifth. They did, however, earn a record amount of ink.

They also got hit a lot. If you believe the stories, this was mostly on purpose, because other drivers thought the cars were dumb.

Factory shoe Rydell again: “To wind them up, in one heat, we drove with a large stuffed collie in the [trunk] during the parade lap.”

A year later, Walkinshaw switched to 850 sedans. A rear spoiler had become legal and shown significant benefit in testing. Crucially, however, BTCC rules did not allow aerodynamic aids to extend above a car’s roofline. As the wagon’s roof went all the way to the rear bumper, any aero addition worth the effort would not be legal. Sedan with spoiler was faster than wagon without.

Brand-new one year, too old the next, like so many great ideas.

***

Aging is one of those experiences we all have in common, like the mental fuzziness just before falling asleep or how a cold can turn your sinuses to lead. If growing old is any different, it’s only because we occasionally seem to have some compass in the matter.

So many choices we make can seem to rudder the path a bit. Except they don’t, really. They just change how we perceive it.

You wake up one day and realize you are no longer young. You still feel that way, though, so you spend 20 minutes digging through classifieds for old Volvos. Thinking about the roads near your house. Taking inventory of various corners and switchbacks, trying to remember all the yumps and ridges.

Places where you could commit, say, a bit more than usual. Take a brief chance, make something happen.

High school was so many things. Painful, tiresome, sleep-deprived, miserable, educational, dusted with fun. The further I get from all of it, the more the details recede, the more the losses cease to matter.

What remains, then, is merely a sense of how important the right people can be, especially if you find them in the right place and time. And how an ostensibly boring old family car can, in the right moment, come to mean so much more than you’d ever expect.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

Great photo of Seth. Apparently he’s giving the side-eye to your daughter in response to her “gift hat.”

I listened to the Hinchcliffe podcast episode last evening. I learned as much about car racing in one hour as in the many decades of my life so far. You do a great job of mixing general human interest material with specific “car guy” stuff. Confession: I thought he was British, given his name. But now that I think of it, “Sam Smith” is just as British. (I will not cite any examples. You’re welcome.)

Sam’s teenage years were rougher than they needed to be and I blame the music. Being a teen in the seventies I didn’t enjoy illegal drugs and the poster of Jimmy Page didn’t tell me my guitar playing was almost as good as his.

A childhood spent watching any type of motorsport competition i could find on 90s tv channels here in Aust means I have more than a passing interest in that era of BTCC. The Volvo wagon stories are legendary: the production cylinder head that was pie cut to improve flow to the intake valves, the aero trickery and yes, the large stuffed collie. On more than one occasion I’ve thought about building a tribute, but with a modern (ish) Volvo T5 turbo out of a early 00s C30 or Ford Focus XR5. This would be a huge amount of effort that could be put towards almost any other car of the era to make something significantly faster, but not as cool. I even know what corner at my local track could be used to generate my own version of that Wheels Up photo.

Also. The 2002 race car bit, “That’s a story for another time” This needs to be told. I have faith that you’ll get to it.

Love it! I’m a fan of BTCC for many years. I’m not super into the new goofy hybrid era, but I do love the incredible fender to fender not too shy about paint swapping action. I also happen to be a fan of long roof cars and will, at some point own a two or for door Chevelle wagon, from the mid sixties.

Great story, Sam! Teenage years can be a very difficult time. I too, spent some time with depression. Fortunately I had a moment, I don’t know what precipitate it, but I had a moment when I just came to the realization that depression just wasn’t any fun. It took some time, but I made it through and was able to move in a much more positive life.

Sam, I always look forward to your writing, and this piece vividly demonstrates why. I’m a 25 laps around the sun ahead of you, but we’ve shared many similar experiences. Something that’s made me happy as I age is the confidence that I have missed out on very little, which led to a somewhat frenetic lifestyle with multiple careers, not to mention over 70 cars owned over the years and three retirements from road racing, all supported by an endlessly patient spouse of 42 years. Instead of saying “I really wish I’d . . .” I prefer to say “I’m really glad that I . . .”

Thank you for your work.

You had me at “Ekranoplans,” and then the ride started.

I like writing that doesn’t go in a straight line, but then, kind of does. Thanks.

The rider in the photos is not Richard Rydell, but Jan Lammers, a Dutch racing driver, as it clearly says on the windows

He’s referring to the quote, who said it. Not the picture.

Wow. Everything. Wow.

Thank you Mr. Smith-this one somehow hits all the notes. High school anxiety, angst and depression, friends who overcome the odds, family, and automotive passion with an articulated kink for station wagons. Bravo.

Exactly – this comment nailed it – both for H.S. and long-roof Volvos.

I worked with Volvo corporate from the mid 80’s through 2001. One of my favorite experiences was a trip to see the BTC races at Brands Hatch. The following year, we flew the racing car to Canada for a press boondoggle at Shannonville racetrack. I got to sit shotgun with Rydell trying to scare the hell out of me. He was an amazing driver.

Our four boys grew up with a Volvo wagon or two kicking around, a white 740t with 300k miles and surreptitiously named “The Coffin” being the High School ride of choice. Our oldest heading off to preschool ensconced in the middle row of the purple 850 wagon he named “Barney”, only later to christen his first car, a deep maroon V70 wagon, “The Bruise”. All have since moved on to Audis and VWs of various sorts, but when it came time to look for a car for this years Lemons Ralley, everyone’s first thought was VOLVO WAGON!

Oh Sam, how I love that picture.. In high school, I secretly wanted a Volvo wagon. In college I got an 85 245 DL that served well for several years. It was replaced by an 86 745 GLE that eventually was rear-ended by a semi truck (and drove away). That was in turn replaced by an 83 244 Turbo Intercooled, a wonderful car that loved to be driven fast, far, and often. It’s was superseded by a 98 V70R, a wagon of refinement, impressive capacity, and sheer power. I’ve owned 2 more first gen R’s since. Last week, I put down a deposit on a 2004 V70R. Proof that given enough Absolut, the Swedes will think a 300hp Volvo is perfectly sensible.

The shot of the 850 wagon up on 2 wheels? That was just the beginning.

On point! I still wish I’d hung on to the 740 Turbo sedan I bought from my in-laws, or even the S40 T5 I had a few years ago. There’s just nothing like sticking to a BMW’s rear bumper, in a Volvo, on the twisties here in Central Texas. Not that I’ve ever done that… I grew up and bought a WRX, but at 66 I still have a hankering for another brick.

The high school portion was almost painful. Get outta’ my head, in a good way.

early on there were a couple of those ’47-ford-looking volvos in the the scca’s southeast division with abarth exhausts; one had a judson supercharger. they were driven harder than street sportscars by guys who’d started a family a bit earlier than most

Always fun to follow this rabbit down the hole. In the immortal words of the Swedish Chef, “Bork, bork!”

Thanks for the expression of love for those 740’s. You really never hear about them at all these days.

I have one in my barn awaiting resuscitation. After reading your essay, I’ll make a point to get to it sooner rather than later…