Media | Articles

How Fast and Furious ruined a generation’s driving technique

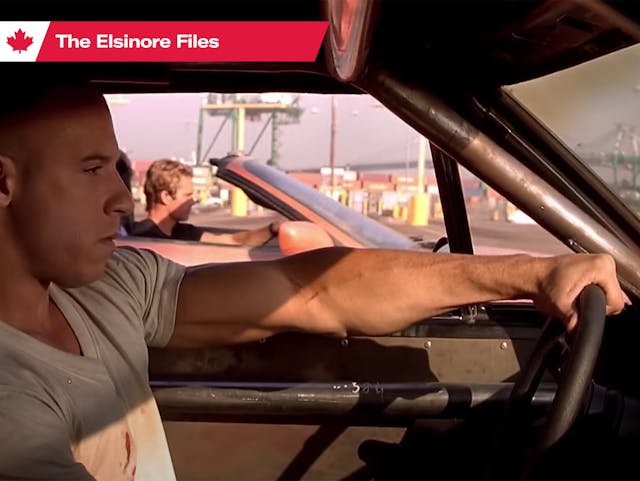

Vin Diesel has ruined seating positions for a generation of drivers.

Yes, I know the exploits of Dominic Toretto are pure Hollywood fantasy. Suspension of disbelief, the tropes, and all of that Tinseltown trickery. But sometimes fantasy becomes reality.

Even without seeing it here on this page, you can call up that image of Vin Diesel seated in his Dodge Charger, left arm outstretched, meaty forearm flexed, hand gripping the wheel at an assertive 12 o’ clock. His attitude, both literally and figuratively, is burned into our collective car-enthusiast memory.

In the real world, we simply can’t handle a powerful car with one hand atop the steering wheel. If we enjoy driving, there’s a right way to sit behind the wheel—and Toretto’s isn’t it.

But life imitates art, and legions of young people have enjoyed the F&F franchise—you don’t turn your back on family—so who else would they emulate when they’re driving? Certainly not their driver’s ed instructor. How about parents? Parents aren’t cool! The muscle-bound bald guy who catapults a Lykan Hypersport through not one, but two skyscrapers? That’s more like it.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Whether I’m in traffic or peering out my office window, it doesn’t take me long to spot one of these perpetrators. Arm extended, reaching with the shoulder to the top of the steering wheel. They can be driving anything: trucks, Teslas, tuner cars. Glancing out my window just now, there goes my neighbor driving his crackle-tuned X6 with its faux M badge. Hand at the top of the wheel, arm thrust forward. Sigh.

As a long-time racing instructor, I’d rather these drivers mimic any top-level racer—get a little closer to the wheel, bend those wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles. Watch any in-car footage from an IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship or NASCAR Cup Series race and you’ll see what I mean.

Still, that’s not what pop culture tells us is cool. Sitting too far from the wheel, hand draped on the wheel to highlight the tricep and advertise how much time we have (or haven’t) spent lifting weights. Recline the seat with some prejudice and now we’re no longer a driver, we’re just a passenger—but that, my friends, is cool.

For years, YouTube viewers have told me I sit too close to the steering wheel. That the way I’m seated isn’t cool. I always ask them to clarify those complaints, but they can’t. What I do know is that I might be the only YouTuber with that one really important racing trophy and decades of instructing experience. I’ve always enjoyed sharing my knowledge with other drivers and I sprinkle the whys and wherefores of an effective seating position across episodes regularly, but it doesn’t matter. The mythology and misconceptions of driving are powerful forces, ones strangely present among Dodge fans who discover my channel.

If you’re reading this, it’s safe to assume you’re interested in driving. We’re here to help you derive even more enjoyment from your time behind the wheel. Assuming your car is mechanically sorted, the next best thing you can do is to improve your driving skills, and to hone those, you have to get the proper foundation: an effective seating position.

Steering wheels in modern cars tend to be designed properly, shaped so that we’re encouraged to drive with our hands at the 9 and 3 o’clock positions. Current regulatory rhetoric suggests that this orientation has to do with airbag deployment, but in truth, it comes down to how humans best use machines.

Fundamentally, we’re visual creatures. When we’re moving—whether running, cycling, skiing, or driving—our brains process that visual data first before sending instructions to our limbs. The way humans drive automobiles requires a tremendous amount of visual data-processing as a first-order function. All relaying of that fun input that we love—like steering feedback, brake feel, and chassis dynamics—comes second.

When we’re approaching a corner, our eyes look into the corner and tell our hands what to do. Our hands follow what we’re doing with our eyes. With our hands at 9 and 3, perfectly opposite one another, we’re in a more natural position to steer the car. When our hands are placed directly opposite of one another, we always know where the steering wheel and the front wheels are pointed. This is basic stuff for those of us who’ve done some track driving, important for those crazy enough to race, and critical for road driving, particularly in those instances when we’re forced to steer quickly to avoid a crash. We’ve all been there, and it’s far easier with our hands at 9 and 3.

Many of us here drive vintage cars, and we know that the classic 10 and 2 o’clock position can be more effective due to slower steering ratios and, perhaps, a lack of power steering; having that extra leverage with your hands higher on the wheel makes turning the car a little easier. If you’re racing a vintage car, I’ll still encourage you to find as close to 9 and 3 as possible.

An effective seating position goes beyond simply holding the steering wheel. We have to be seated relatively close to the wheels and pedals so that the smaller muscles in our limbs can handle the control inputs to the car.

When we sit close to the wheel, we’re forced to use those auxiliary muscles in our hands and wrists and feet and ankles to tell the car what to do. Not only are our inputs on the wheel and pedals more precise, but we’re able to pick up on feedback cues a little better, which is critical in modern cars with their often-numbed steering and brake feel. Sitting further from the wheel and pedals means that we’re using the larger, brute-force muscles in our upper arms, our shoulders, and legs to communicate with the car.

Here’s an analogy. Imagine picking up a pen and writing a note as you normally would. You’re using the most delicate muscles in your fingers and hand to manipulate the pen. Now, imagine picking up the pen but flexing your muscles in your fingers, hand, and arm, as if they were in a plaster cast, which leaves you writing with your shoulder muscles. What do you think that’ll do to your penmanship? The same principles apply to driving: Use the small muscles in your arms and legs to communicate your inputs with the car for maximum control and feedback.

Just like those occasions when we share our passion for manual transmissions, we have a responsibility to share our knowledge about how to sit behind the wheel. Dom Toretto may look cool with his arm extended, street-racing his Dodge Charger on the big screen, but if he tried to drive like that in the real world, he wouldn’t be a driver. He’d be a passenger.