Media | Articles

Avoidable Contact #65: In defense of premarital, even teenaged, SX

They say that when you adjust for inflation, $4200 in 1988 is something like $9200 now. But it’s more than that. My father was a patient and conservative investor. Putting $4200 in the S&P back in 1988 would yield 50 grand today. He was also smart enough to hop in on some tech stocks before it was too late.

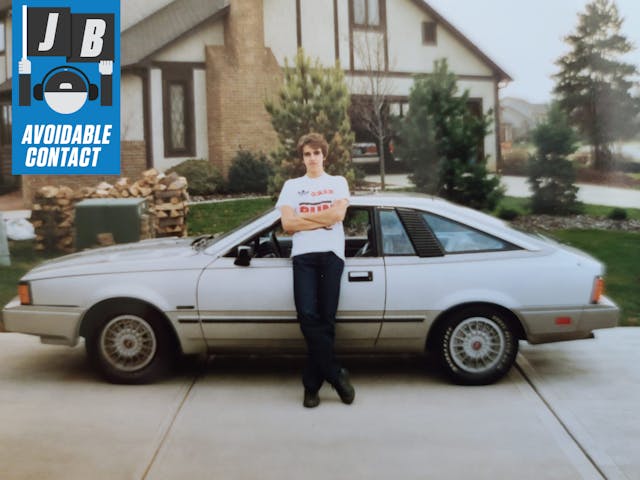

Let’s say that it would be closer to $150K now, given the way his choices have gone. So that $4200 check my father signed over to Jack Maxton Chevrolet in October 1988 was really a $150,000 check, in a manner of speaking. Today, that would get you a used Huracan, a mint Viper ACR, two Ferrari Challenge cars with documented maintenance. In 1988, it got me a 1983 Datsun 200SX.

I couldn’t sleep once I had it. Particularly since I didn’t yet have my license. Just my “temps.” When the sun went down and my family went to bed, I would slip the front door silently open and then walk barefoot to the driveway and sit in the synthetic-wool seat, shifting through all five (five!) forward gears. The nights would pass in mostly insomniac exultation; the days were whipsaw combinations of minimum-wage drudge work and the ecstatic moments when I could get someone, anyone—a parent, my guitar teacher, an older friend—to sit in the passenger seat while I stalled and surged my way around various suburban neighborhoods. After perhaps 300 days as a right-seat trackday coach, I doubt I’ve ever been as badly scared as my mostly unwilling passengers so frequently were in the fall of 1988. I had Senna’s sense of potential gaps in traffic, fingertipping the 52,000-mile Datsun through lurid lane-changes with Pac-Man reflexes and a space invader’s attenuated sense of self-preservation.

The 200SX was a more than reasonable compromise between the car I wanted, which was a Corvette Z51, and the car I should have had, which was a pair of Air Jordans. At the time I was more than a little upset that we hadn’t been able to find a two-door hardtop instead of the fastback hatch, but I cannot remember why. The 200SX with a trunk was considered sportier, maybe. In 1988, hatchback meant “economy car.” Which this wasn’t, not by any stretch of the imagination. It was a big (175 inches, almost a Porsche 928!) and powerful (103 horsepower, in an era when the Accord had 86 and the 911 had about twice that) vehicle with upscale interior furnishings, but no tape player.

There was a newer 200SX in showrooms, of course, a so-called “S12” to my “S11.” It could be had with a turbocharger. My mother knew a woman who owned just such a car: black, stick-shift, turbo coupe. Notchback. She was gorgeous and impulsive, an older woman with perfect makeup and impeccable style, newly divorced. My mother told me, with audible disdain, that she was “certainly enjoying her freedom.” This sounded promising. It occurred to me at the time that we now had something in common. I rehearsed my opening lines to Miss Turbo SX until they were perfect, but when the moment came to make the pitch I was reduced by terror to a stammering sort of two-handed gesticulation where I pointed at both cars and mumbled in what I now perceive in hindsight to be a vaguely threatening manner. She slipped around me with practiced ease and disappeared into our house. “Go ride your bike,” my mother said.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“I don’t have to,” I snapped back, “I have a 200SX now.”

“Go sit in your 200SX,” she replied. In a way, it was a relief. I was an ignorant 16 and my fellow Nissan owner was an experienced 27. Which makes her 59 in 2020. She restores antique homes with her third husband, whose name sounds suspiciously made-up, like the fellow had been watching Downton Abbey with the court forms in his lap. Who would have thought that we would both grow up to be so respectable?

What if I hadn’t found a 200SX? It would have been OK. There were so many great cars for young people, dozens of models on the new and used markets with enthusiasm and aggression either baked into their souls or added courtesy of a tape-and-stripe package. Did you want something in the way of a used car, under 2500 pounds, five-speed transmission, lively to steer, relatively easy to fix? There were dozens of choices, Celica to Cavalier. GT-S, Z24, Escort GT. Five-liter Mustangs. If you could turn a wrench you could buy a BMW 2002 or Porsche 914 for pennies on the dollar. On the high end of things, there was a kid who drove a Ferrari to my high school. His dad got it cheap because there was a new Ferrari, called the Testarossa, that everyone wanted. My classmate’s bargain-basement coupe was called a “Berlinetta Boxer.”

As a kid in this era you were just dropped into a soup of cars with sporting intent. They were all around you, in every grocery store parking lot and on every suburban street. Objectively speaking, all of them would be easy meat for my 2017 Silverado LTZ 6.2-liter Max Tow, either in a straight line or (shhhh) around a road course—but they didn’t feel like that at the time. A lot of young people didn’t start out as “car guys,” but they became that way when they bought something like a General Motors J-car with a big-swaybar suspension option.

No matter what you bought (or were given), chances are it was noisy, harsh, a little darty under power. You had to be involved in the process of driving. It was impossible to guess ahead of time how someone would behave behind the wheel. During my freshman year at university, I caught a short ride once with a young woman in her 1989 Ford Probe, and to this day I can’t believe Frank Williams didn’t roll around the corner at the end of it and offer her a contract. Her car had 10,000 miles on it and the cords were showing on three of the four tires.

It was an era of massively enthusiastic cars in the hands of utter non-enthusiasts. In particular, the five-speed E28-generation BMW 535is, which was seemingly factory-tuned to produce the most lurid powersteer possible but yet was driven by every soccer mom and lawyer dad in the neighborhood. You’d see them off the road every time it rained, two long furrows in the grass leading up to their current resting place. I still remember driving at irresponsible speed under a bridge overpass one night and being briefly terrified by the friendly frog face of a 911 Carrera Targa emerging from the bevy of bushes it had recently entered tail-first. The features behind the windshield were drained bloodless white but were still recognizable as the fellow who owned a few local fast-food restaurants.

Here at Hagerty we talk a lot about preserving the joy of driving for future generations. Because many of us are now what you would call connoisseurs, this often takes the form of, “Let’s show these kids a Dino,” or “Let’s drive some teenagers around in a Vignale Spyder.” That’s wonderful and important, but it would be a lot more helpful if we could somehow find a warehouse filled with showroom-new Cavalier Z24s that could be strategically placed at used-car lots next to Mom’s old CR-V and Dad’s old BMW X3. We have plenty of nice cars to share with kids. What we need are some lousy ones that nevertheless spark the possibility of a lifelong passion.

I already own about the nearest thing to a 1983 200SX you can find nowadays—my 2014 Accord V6 Coupe avec clutch. My son is fairly uninterested in cars—he likes to race proper karts, but that enthusiasm doesn’t translate into roadgoing automobiles. I am hoping the Accord does yeoman’s work in converting him to our cause, that he will see it as the kind of personal rocketship my 200SX was to me, an authentic first love in a life of many attachments to come.

My first love, it should be noted, didn’t last very long. I crashed it before I even got my permanent license, with an 18-year-old co-conspirator in the passenger seat. It was back to shank’s mare for me. I rode my bicycle to a variety of crummy restaurant jobs in the 18 months between totaling one car and grifting my way into another one. It didn’t matter. This was not the sort of flame one can easily extinguish. In the 30 years after that I would go on to buy more than 60 motor vehicles on my own dime. Today I have, uh, something like three race cars, three-and-a-half motorcycles, seven street cars, and various other projects and ideas. Out of justifiable penitence I lent two of my Porsches to my father for a few years until I thought we were close to square—on the automotive side, at least.

They say that when you adjust for inflation, $4200 in 1988 is something like $9200 now. But it’s more than that. In a world where I start my driving career with a hand-me-down station wagon (trust me, kids, those were NOT COOL in the era before the sport-utility-vehicle showed us just how deeply uncool a vehicle could really be), I probably don’t go on to work for various car dealerships, finance companies, performance tuners, and “buff book” magazines. I’d be just another frustrated face on the freeway, just another middle-aged man with no passion for driving and consequently no driving passion.

It is any wonder I still think about that 200SX from time to time? Forty-two hundred bucks. It was a lot of money. It was money well spent.