Media | Articles

Avoidable Contact #62: The ballad of the first owner

The first owner is a ghostly but still powerful presence in the nooks and crannies of the old car we have just bought. Microscopic remains of his incomparable skin and sweat dwell deep in the foam of the seats. A pair of shiny spots on the wheel indicates where he liked to rest his princely hands during long trips, utterly and completely free of all our mincing worries about wear and tear and NLA parts and suchlike. The frame of the drivers seat has a slight twist from his tendency to lounge in traffic. He was restless, a wealthy and predatory creature trapped in a cage for which you would eventually pay dearly, but not as dearly as he did. He was Adam, Genghis Khan, Columbus, Armstrong, the first man. We will never be completely free of him.

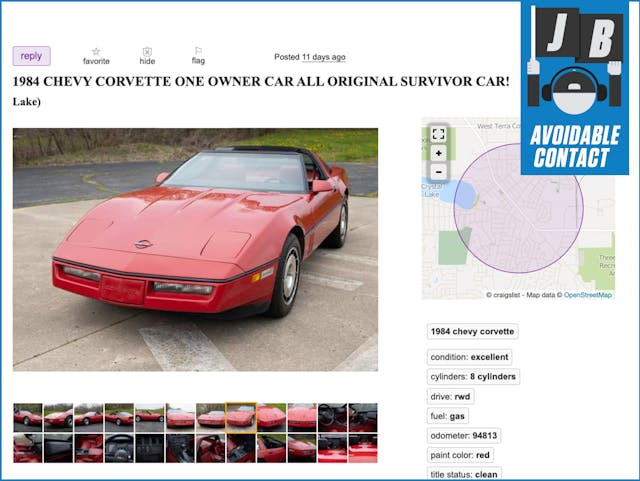

He is difficult to understand at a distance, the first owner, much like God is to children or the Federal Reserve is to adults. We know why we buy these distinguished old enthusiast vehicles, these aircooled Porsches and droptop Benzes and Z51 Corvettes, but we can only guess at his motives. This cherished car of ours, the one we searched for over the course of a decade or longer, the precise and perfect assembly of color and option and specification? He bought it on a whim, bought it on a lark, bought it on a Friday afternoon after the market closed but before the final tee time. It was the only one in stock. It was the same color as his wife’s favorite dress. It was the one closest to the showroom door.

If we are lucky, we have the original documents of sale, which tell a fantastic story. The first owner paid cash. He traded in a car of greater value, possibly a Camargue, and received a check for the difference. He financed all of it, including the license fee, and asked for a hundred dollars in singles back. He negotiated it down to invoice minus holdback because he held all the cards in the negotiation. He paid full sticker because he didn’t care. In the years to follow, he had it serviced … at astounding, magnificent cost! First by the dealer, then by an independent shop which would grudgingly provide a few scribbles’ worth of weak justification above a five-figure total due. A blue stamp with changeable red date in the center informs us that the bill was “Paid In Full” immediately. He permitted repairs which boggle the mind: multiple blower motors in a Benz R107, vacuum power windows in a 600 Grosser, belt replacements in a Testarossa. There is no indication that these outlays inconvenienced him in any way.

As we climb through our new acquisition, intending to preserve it for time immemorial in the long term and a local concours in the short, we are everywhere confronted by his superiority to us. Our brows furrow at a quarter-panel crinkle behind the bumper from when he drunkenly smacked a neighbor’s car after a long formal-dress dinner party and never thought to address the damage. There is a seemingly ineradicable red wine stain in the rear seat courtesy of his close friend’s second wife, whom he pursued indifferently but successfully over a season of doubles tennis, then promptly forgot after the fact. Over the next three weekends we will disassemble the transmission and weld up a new parking pawl to replace the one he destroyed on a vertiginous San Francisco street when he threw the car in park and jumped out to confront a business rival face to face. Blood from the knuckles of his right hand has decomposed to a fine brown powder in the stitching of the shifter boot.

The first owner traded in a Cadillac de Ville for a lithe wedge of a sports car, then traded back for another de Ville two years later. The features which dominate our dreams at night—the optional limited-slip differential, the chairs and flares, the Vader seat—made no impression on him at all. Or if they did, the impression was that he should have saved his money. The first owner took the cash he could have spent on the P030 Performance Package and used it instead to specify designo paint. His friends and associates don’t remember him caring about the car in any particular way. “The Ferrari that Bill had? Oh yes—he used to leave it under a maple tree all summer.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

A rare photograph shows the first owner with his car, in the driveway of his home, having just washed it. His perfect children frolic and gambol on the lawn. His wife is perfectly dressed for the era, perfectly beautiful. The first owner is smiling, because he has no reason not to. Most of the car is out of frame. Nobody thought it was important at the time. With just a few extra millimeters of Kodak 110 film, we could see whether or not it actually shipped with the wheels it has now—but we might as well ask for photographs of Bonaparte. There’s a license plate frame visible in the corner of the photo; it’s an original stainless-steel item from a famous dealership, it would fetch $500 on eBay, were it not somewhere in the landfill an appropriate distance from the first owner’s summer home.

He does not remember much about our car. Should we manage to find him, we will admire the erectness of his carriage, the clarity of his uncompromising and rheum-free eyes, the casual way in which he wears the most expensive clothes—but we will not learn anything relevant to our automotive interests. We will hear stories in which the car plays a part: a midnight drive along the PCH to meet a mistress or close a deal, a summer in the city before he “really made the money,” a memorable afternoon in the company of another justly famous personage. Our car will have figured in the tale, but it could just as easily have been a 1983 Pontiac Phoenix for all the difference it made. (If our car is a 1983 Pontiac Phoenix, then we will reflect that a Citation would have served equally well.) The longer we speak to the first owner, the more we will realize that he doesn’t care about cars at all. So why did he buy this ferociously enthusiast-focused vehicle? Did he simply not know any better? Or did it just not matter either way?

Nowadays, he drives a Land Cruiser, or an S-Class, or the latest in a series of identical GT-whatever Porsche 911s, purchased with identical specification once every 24 months at a discount from a old-friend dealer, then resold by his executive assistant into a pool of drooling new-money supplicants. He is the living embodiment of an uncomfortable fact, namely: that the vast majority of enthusiast vehicles are initially purchased and operated by people who simply consider them to be another accouterment of success, no different from the currently fashionable Rolex or the latest McMansion or a NetJets card. The first owner would always have been more satisfied with something like a Porsche or AMG sport-utility vehicle, those warp-speed minivans which carry today’s #Blessed crowd to wine tastings and farm-to-table restaurants and invitation-only social events with blunt-faced menace and computer-controlled exhaust pops at just the right moment. It’s just that no such thing existed back then. What seems in retrospect to be an admirable commitment to manual transmissions and cramped quarters and widow-making handling characteristics was really just the natural consequence of having no other choices at the time.

The future holds no terrors for the first owner. He has seen next year’s brochure, he’s attended a private event to hear more details, he’s already been quietly contacted by interested parties. The new powertrain, the one which substitutes a bland turbocharged variant of a truck engine for the old handbuilt 9000-rpm race mill in exchange for a 3-pound-foot increase in torque between 900 and 907 rpm, seems just ducky to him. He inquires about the possibilities for pairing tablets to the infotainment system; his grandchildren are interested in this. “It has a manual transmission,” he tells his newest girlfriend. “You shift it with paddles.”

An event is held in his honor, by the local dealer. He is escorted in by people who are financially delighted to see him. The ice sculpture meets with his approval. A cadre of fawning fellows show him watches, jewelry, investment products. His newest car is there, in the center, under a spot-lit sheet. A local magician has been hired to make the sheet disappear at the appropriate time. The magician’s assistant is wearing foundation makeup on her wrists to cover a recent attempt at self-harm instigated by losing her day job in a balance-sheet-related layoff at one of the companies in which the first owner has a majority interest. A mix of 2012’s Calvin Harris set at Hakkasan plays in the background, turned down to the point where only the bass hits can be heard, which makes it sound as if animals are fighting over fresh meat in the cater-waiter kitchen behind Parts and Service. “Thank you,” the dealer principal intones as he points at the first owner, “for being exactly who you are.” The magician gestures dramatically. There is a loud bang! and someone laughs nervously. The sheet has disappeared. The world’s first nine-seat sport-touring-utility-GT-Carbon-Exclusive edition vehicle is revealed. All eyes turn to the first owner.

“I thought it would have 10 seats,” he whispers to his girlfriend, who was previously his home care assistant. “I have four grandchildren—and they despise each other.”

“It can have 10 seats,” she whispers back, smiling vaguely in the direction of the audience. “You can have anything you want.” The dealer principal leads the room in a series of exuberant cheers. Then there is a noise so loud we can taste it, and the room fades out of view and we realize that none of this was real, that a recently-recalled “imported” jackstand failed three minutes ago and that our project car has been crushing the life out of us since then—that these are the final flashes of our desperate neurons before we die. We are found the next day and unceremoniously burned at a discount funeral home. Our car is sold at an estate auction to pay our outstanding credit card debts. The buyer is a sharp-dealing fellow who runs a mostly online store for “youngtimer” classic vehicles. He receives a visitor, someone not too unlike us. This fellow walks around the car, sees where we have polished the paint and straightened the crinkles and resurfaced the leather, where we have done our level best to make this old car look as new as possible. He folds his arms in front of his chest and turns to the salesman.

“Tell me,” he demands, “about the first owner.”