Media | Articles

Avoidable Contact #61: The tricky ethics of building a Camargue for everyone

If there’s such a thing as Automotives Anonymous, I’m never going to get a sober coin. In the past 14 months I’ve bought … ah, hold on, let me count … six cars and sold just one. My wife and I are now at the point where we are hiding Miatas and Neons and full-sized Mercurys in random garages the way that alcoholics are known to keep a bottle in toilet tanks. Friends and even acquaintances have learned not to mention the existence of an empty driveway slot on their properties, lest we pounce on it with the fanatic fervor of a multi-level-marketing representative asking you if you’d like to work with major companies such as Coca-Cola. Including motorcycles, we have either 21 or 22 gas-powered vehicles, depending on whether my pal Sidney is ever going to let me ride the Yamaha FZ-1 we bought as a cooperative project back in 2017.

This level of ownership, while well short of the collections enjoyed by many Hagerty members, brings up what feels like an ethical dilemma to some younger and more socially-conscious members of our community. We all understand that it’s not feasible for every human being on the planet to own 10.5 cars each. It’s probably not feasible for every human being on the planet to own one car each. A publication devoted to the glorification of “microliving” and whatnot recently wrung its hands in public about New York City having 1.85 million parking spots. The sheer waste of it! Think of how many nightclubs and bakeries and pop-up denim stores you could fit in all that space! Yet that’s just one parking spot for every five New Yorkers.

Even if we could park ’em all, we can’t make them all; an auto industry which fulfilled Henry Ford’s Model T dream on a global basis would have to produce perhaps 20 times what it produces today for decades to come. Getting the raw materials to do that would be virtually impossible. Once you’ve built them, you have to fuel them, using either politically volatile hydrocarbons or battery power. As for the former, it couldn’t be done. As for the latter, the materials in electric motors are called “rare earths” for a reason. (No, many of them are not actually rare, but they are all expensive to mine, separate, and process—both in terms of cash and energy.)

You get the idea. Not everyone in the world can have a Silverado LTZ or a Mercedes-AMG S63. They can’t even have a Smart car. Getting everyone a 49cc Honda “Scoopy” scooter is probably pushing it. This has led a lot of young people, even people who consider themselves to be automotive enthusiasts, to adopt an attitude about the privately-owned car which is somewhere between guilt and active sabotage. They engage in long public self-flagellation sessions regarding the environmental and social impact of the automobile. (Which, if you compare how people lived in 1920 to how they live in 2020, has been much more positive than most public-policy types would like to admit.) They agitate for democratic-socialist strategies like high gas tax, mandatory speed limiters, and other leveling measures. Yesterday I read a suggestion that each individual citizen should be given a certain amount of fuel flow per second on the move, the same way that some race series limit injector size and pressure. “That way, a Lotus Elise can go really fast and a pickup truck has to go really slow.” Why this is a good idea, or how it would lead to anything other than leather-jacket-Mel-Gibson levels of carnage on the road, was not explained to anyone’s satisfaction.

For me, this apparent ethical dilemma is resolved in a couple different ways. The first is my steadfast belief that Harrison Bergeron was a cautionary tale, not an instruction manual. I don’t resent Bob Lutz because he owned a fighter jet. I hope that the fellow on a scooter doesn’t resent me for having a Mercury Milan 2.3-liter five-speed. I hope that the fellow without a scooter doesn’t resent the fellow who has one. In any sane world, some people will have more than you have and some will have less. Every attempt to rectify this with science and rational thought has led to nightmare levels of violence. You start out with something reasonable sounding like, “Hey, maybe people shouldn’t have to eat dirt in order to survive,” and you end up killing people because they wear glasses or know a foreign language, Khmer-Rouge-style.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The other way in which I rationalize ownership of a 208-horsepower motorcycle and whatnot is this: Human beings tend to specialize in consumption. I buy a lot of cars, but I don’t have much of a house. You might travel to Europe six times a year while living in an 800-square-foot apartment. Some people are out there at different restaurants every night but they wear thrift-store clothing. You get the idea. Only the super-rich have the best of everything. I’ve been using the same microwave since April 2001. It broke on Monday, by the way.

If we follow the above thoughts and justifications to their logical conclusion, however, we come up with a nasty piece of business that reads like so: It’s OK for some people to have a Rolls-Royce Camargue, but not OK for everybody to have one. I mention the Camargue because it was the first Rolls-Royce I remember seeing in a dealership, circa 1982 or so, and because I just finished Malcolm Bobbitt’s book about Silver Shadows and their derivatives. You might not like the Camargue—not many people did—but I think it’s gorgeous. It has real presence to it, and it’s not beautiful in the manner of an E-Type or 250 GTO that’s alright. I’m kind of a Camargue myself. Larger than the average fellow, unlovely around the edges, with a face to clear traffic out of the left lane.

The Camargue was the most expensive British car of its time. One writer noted that on its debut it was priced even with English city townhouses which now fetch north of $7 million. It wasn’t actually that large of a car, casting just a little more of a shadow than a 1976 Cutlass Supreme, but it was thirsty and it consumed tremendous resources in its creation. Rolls-Royce didn’t get a thousand of them out the door over a 15-year period, no surprise given its appearance and cost. From what I’ve read, some people who could afford a Camargue chose to buy a less-expensive Silver Shadow instead, just because they didn’t like the social messaging of buying something that outrageous. I can attest that it took the Columbus, Ohio, Rolls-Royce dealer well over a year to sell its white-with-black-leather example. Midwesterners, even wealthy Midwesterners, can be a little diffident about driving a Rolls-Royce, to quote Mr. Ogilvy.

Big and brash it may have been, but the Camargue wasn’t even a blip on the planetary balance sheet. Using a Hofstadter approach to the problem, I estimate that the entire Camargue production run had less impact on the environment than, say, the annual operation of an F-22 squadron or perhaps even the life cycle of a single Regional Jet. If the polar ice caps melt into the sea and the Adirondacks become beachfront property, you won’t be able to blame the Camargue.

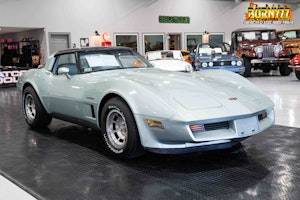

Could you blame the Bonneville? My friend and fellow Hagerty contributor Tom Klockau just found this gorgeous 1978 Bonnie coupe for sale. It reminds me of the Camargue in its profile and its pressed-crease edges. Compared to the Rolls-Royce original, it was about 10 percent longer, that much more spacious at least, and just as powerful. Heck, I think they have the same transmission and steering gear. If you buy it, let me know and I’ll meet you somewhere to pay for your dinner.

Pontiac didn’t sell a lot of Bonnie Brougham Coupes, but it moved a fair number of B-body cars overall. The nearly-identical Impala/Caprice moved a million units in its debut year of 1977. I’d guess that GM sold maybe 10 million full-sizers of this generation total. That’s 15 thousand or more LeSabres and Eighty-Eights and whatnot for every Camargue. Each of them requiring a similar amount of glass, steel, rubber, and fuel. That probably did make a dent in the planetary resources, although perhaps not like the Chinese container-ship trade or the Airbus A380.

It’s possible to have an ethical stance on the automobile which allows for the Camargue but denies the Bonneville’s right to exist. The numbers would be on the side of anyone who felt that way. We cannot issue a Camargue, or a Bonneville, to every human being on Earth. Some of us will have to go without the unalloyed joy of full-sized coupe ownership.

How should that joy be restricted, demarcated, parceled out? Some of my younger contemporaries will self-righteously declare something along the lines of “nobody needs that car,” perhaps unaware that they are sitting in a tent while eagerly tugging on the curious nose of a totalitarian camel. Others may declare that the full-sized coupe should be available to anyone who can afford it, even though it’s possible to imagine a scenario in which we bankrupt the earth’s crust doing so. There’s always a temptation for older people to pull the ladder up behind them; “Sure, we had V-8s for everyone in my day, but now that I’ve had my fun I think that the next generation should be conscious of the environment and their responsibilities to it.” That attitude strikes me as occupying a moral ground somewhere between hypocrisy and outright evil.

If we wait long enough, perhaps technology will solve the problem. Imagine a machine (or, given the way things work now, an app) which reads your mind and determines what you truly want most in the world, then somehow clears the path for you to get it. If you truly love being a foodie, you get to go to all the restaurants where they torture geese or whatever’s going on in there, but you don’t get to buy a new Tesla chock full of environmentally-dodgy batteries. If you want to own a jet plane more than anything else, maybe you have to live in a micro-apartment and eat ramen noodles in between flights. There are no doubt people who have other desires which cannot be printed in the virtual pages of this family-friendly website; maybe they can exercise those desires, but they can’t go to a Bass Pro Shops, ever.

As for me? What happens when I press that scanner up to my forehead and get my allocation of passion? Will it tell me to stay at home and play guitar? Go out and ride my BMX bikes? Could it decide that I have to focus all my economic power and attention on the maintenance of my ragtag race car fleet? Or maybe, just maybe, will I hear a triumphant little jingle from my smartphone’s speaker, followed by an on-screen notification that I am finally going to live my automotive-addict dream? That I will finally be the owner of a charmingly-ugly, leather-lined, bi-level-climate-control-equipped … Rolls-Royce Camargue?