Media | Articles

Avoidable Contact #153: More than just a $160,000 plastic Mustang from China

Some cars are works of art; the Polestar 1 is a work of modern art.

This is not necessarily a compliment.

For most of human history, “art” was simply a term for creative efforts that rose above mediocrity in service of what was called “the true, the good, and the beautiful.” It was traditionally judged by how effective it was at conveying a sense of humanity, either through portraiture or sculpture or literature. Visually, our species started with cave paintings and ended up with the superbly accurate portrayals of the Victorian era. As far as storytelling goes, one day it’s graffiti in a pyramid, then it’s Beowulf, then you’re at Henry James. Boom.

Somewhere around the First World War, art took a sharp left turn and began existing in context. You get stuff like Suprematist Composition: White on White that could be painted by a five-year-old but which represents a sophisticated (perhaps over-sophisticated) approach to artistic criticism and context. White on White only makes sense if you’ve spent your life examining the most detailed paintings humanly possible and you’re ready for something that speaks to your perspective instead of just being another portrait.

Naturally, there was art made in response to White on White, and art made in response to that art, and so on. We are now at a point in history where it is difficult to understand a lot of today’s creative work unless you are thoroughly steeped in every fine-grained aspect of the relevant context. Anybody can look at the Mona Lisa and say, “Hey, that looks a lot like a person, and that’s cool.” By the time we get to The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, you almost need an MFA not to see it as just a visual prank on the phrase “shark tank.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

So with that in mind, let’s take a look at the Polestar 1. If we look at it with just a minimum of context, basically the information that any adult “car guy/girl” has available in the cerebral cortex, then it is an astoundingly expensive car with a four-cylinder engine, a plastic body, and a final assembly point in the People’s Republic of China. It resembles a current-generation Mustang more than it does any Volvo in history. The interior is nice but it’s essentially identical to what you get in the upscale trims of the Volvo S90 and XC90, neither of which costs $160,000 with matte-finish paint. It can run the quarter-mile in about 11.9 seconds at 121 mph, almost exactly what you get from a Shelby GT350R but well adrift of the average six-figure performance car. On the road, it makes a lot of weird noises. It weighs a lot—a lot, I won’t say how much or you’ll think I’m lying. Compared to something like BMW’s M8 Competition, it’s an absurdly tough sell. Other than fuel economy, I can’t think of any metric where the Polestar 1 exceeds or even meets the big Bimmer.

For most people, including your knuckle-dragging caveman of an author, here’s where the story ends. For this kind of money I’d rather have a Radical SR8, a stick-shift Mercury Milan, and a Bricasti M12. If we look at the Polestar 1 that way, however, we are missing out on a lot of context, some of which is worth absorbing even if you will never be in the market for a car like this.

To begin with, it is an unapologetic statement of Volvo’s aggressive futurism. Long before it became an appendage of Chinese automaker Geely then had a highly-publicized “Swedish IPO” in which the majority of shares just happened to fall back into Geely’s hands, Volvo was pushing the limits towards what it saw as the inevitable future. The firm’s 1975 Lambda-Sond system previewed the eventual industry standard of feedback-conscious emissions controls by about a decade. Volvo was an early adopter of turbocharging. They were doing deals with other automakers long before that was an expected part of the business, from the “PRV” V-6 shared with the French to the Dutch small-car collaborations. They went FWD more than three decades ago. The original XC90 was arguably the best-executed first-generation luxury SUV of all time. You get the idea. Volvo likes looking ahead.

In that context, Chinese assembly isn’t a cheap-skate way to save a few bucks on a car that costs almost as much as a Porsche GT3; it’s an unsentimental expression of Volvo’s belief that automobiles, like many other manufactured goods, will eventually be made almost exclusively in China. Although our test vehicle was delivered with a plastic cling that defined Polestar as “a new Swedish performance brand,” both the Polestar 1 and its cheaper, less ambitious Polestar 2 sibling are essentially Chinese. The plastic body, reinforced by carbon fiber, is an innovative way to do small-batch production much like fiberglass was in the days of Colin Chapman. The absurdly complex drivetrain—turbocharged! supercharged! three electric motors, capable of driving the rear wheels individually!—represents a foray into the outer limits of a configuration that does yeoman service in T8-badged Volvos, minus one of the rear motors. Even the styling becomes vaguely reminiscent of the handsome current Volvo S60 if you stare at it long enough.

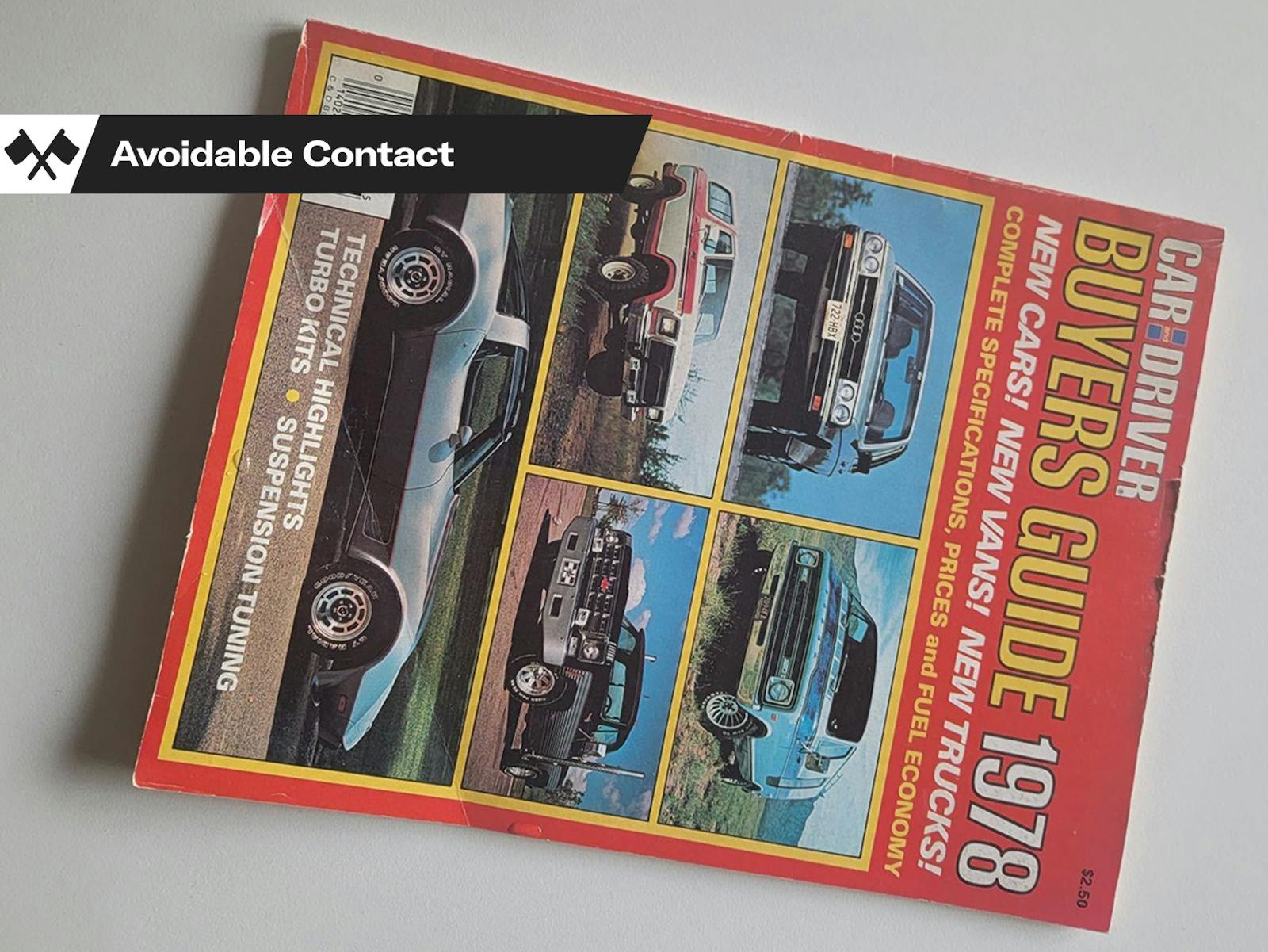

That’s a lot of explanation for a car at this price level, but there’s precedent for it: any car magazine of the ’60s or ’70s will boast numerous wall-of-text advertisements trying to get the suckers used to the idea of paying twice, thrice, or even seven times the price of a nice Sedan de Ville for various poverty-spec, compact-sized, vinyl-clad sedans and GT cars from Europe. There really was once a time where BMW ads were just long explanations of what a BMW was, accompanied by a blurry photo taken about an hour after sunset. The irony is that it was perfectly obvious at the time what a BMW was. It wasn’t until the current decade that the company’s lineup became bizarre enough to actually require an explainer.

Having studied up on the significance of the Polestar 1, I took it for a drive in the company of Art Director Matt Tierney and Road Test Editor Alejandro Della Torre. Now this is the point where I admit that I kind of like the wacky Volvo T8 powertrain. A few years ago I drove an S90 T8 across Thailand at constant velocities of up to 140 mph and I was thoroughly impressed. In this car, it makes about a Huracán’s worth of power. The manner in which it does so is infinitely more complex than that of a Huracán. There are times when you can kind of feel all the systems arguing about the best approach to take when considering the requests of throttle and steering wheel. But it works about 95 percent of the time. I particularly like the “B” mode, which is the most efficient one possible and maximizes your engine-off time in traffic.

This chunky coupe doesn’t really “corner” the way a GT350 or M8 corners. It has a tremendous amount of mechanical grip courtesy of massive tires. You won’t reach their limits in any normal operation. If you push the Polestar beyond design intention, however, say by doing 60 mph into a marked 25-mph corner, there will be a lot of mechanical agitation as the four driven wheels balance their power application in real time. Then the car will settle in and grind off the edge of the outside front tire in a manner familiar to any K-car owner. What can I say? If you want a backroad blaster, get something else.

Away from the twisties, the Polestar 1 comports itself with dignity. The interior is quiet and the sound system is good enough for a car with this price tag. The interior might be straight out of an XC90 but that’s like saying that the Coyote engine in a Mustang GT is straight out of an F-150; it’s still great regardless of origin. The rear seats are significantly less usable than the rear seats in, say, a 1970 Porsche 911. They’re more like the punishment bench that the U.S. Government made Mercedes-Benz take out of the 450SL in order to meet our crash standards. This is a two-seater car for anything more than a run to the corner store. I’m not sure you could fit a child seat back there, even a front-facing one.

In Hagerty Media’s home town of Ann Arbor, Michigan, the Polestar gets a lot of approving and envious looks from professorial and health-food types. I doubt they know exactly what it is, but it’s clearly cut from a different cloth than the brash-and-bold, sheikhs-and-Bitcoin big coupes from BMW and elsewhere. There’s a lot of nice surfacing in the body panels, making the Polestar look muscular from most angles. The chop-top roof is probably a tribute to the similarly headroom-challenged Volvo 262 Bertone coupe of thirty-five years ago. I like it.

On the other hand, I can’t say that I like the future described by the Polestar: complex electrified powertrains, massive curb weights, assembly by the lowest bidder. That’s okay. I’m not a fan of modern art, either. But there’s an enthusiastic buyer for every “balloon dog” Jeff Koons can make, and I think there is a powerful, educated, and highly compensated demographic that will truly enjoy this vehicle. We’re talking about folks who would consider a Mustang to be infra dig and a BMW M8 doubly so, people who attend both the Arts Basel with checkbook in hand, automotive enthusiasts who consider first and foremost what kind of statement a car will make when it’s filling up every inch of a parsimonious driveway between a beach house and the PCH. By their standards, the Polestar 1 is a winner. More than that, it’s historically significant. Someday, all performance cars may be like this.

When that day comes, I’ll be somewhere else.

Doesn’t look bad, although – as the author says – it looks a lot like a Mustang. The way-too-complex powertrain, and the Communist China assembly point, mean it would never be in my driveway. If I was shopping in this price arena, there are way too many better offerings, both sport and luxury.