Media | Articles

Avoidable Contact #144: Collection, accumulation, and Miles (Collier) to go

Any student of the 18th century, as I once was, will be familiar with references to “the Great,” with a capital G, meaning the aristocracy. The world of Samuel Johnson and Alexander Pope was entirely dominated by people whose inherited status or recently-earned wealth had admitted them into a different class of humanity altogether. Nothing serious could happen without their consent and/or involvement. You might be the finest writer, or boxer, or dancer, in human history, but until you were “acquainted with the Great” you weren’t going to get anywhere. They had most of Europe in an utterly iron grasp enforced by blood and starvation. It was their world, not yours.

Understanding this view of society comes very easy for “Generation Z,” since they have grown up in a BigTech dystopia folded, spindled, and mutilated out of the American dream by people whose disconnection from normal human existence would make Crassus blink in shock. For GenX-ers such as myself, however, who have fond if fuzzy memories of a time when human beings were not degraded into a variety of “ubers,” “doordashes,” and “task rabbits” for our own convenience, this notion of a double-decker society can be a bit hard to swallow. Count me in with Voltaire, who crossed the English channel to visit the poet Congreve, only to be annoyed by Congreve’s “despicable foppery” of wanting to be treated as a member of the Great rather than on his merits as an author. Voltaire’s deadpan response that “I can see aristocrats at home; I came to visit an artist” is exactly in line with my own thinking.

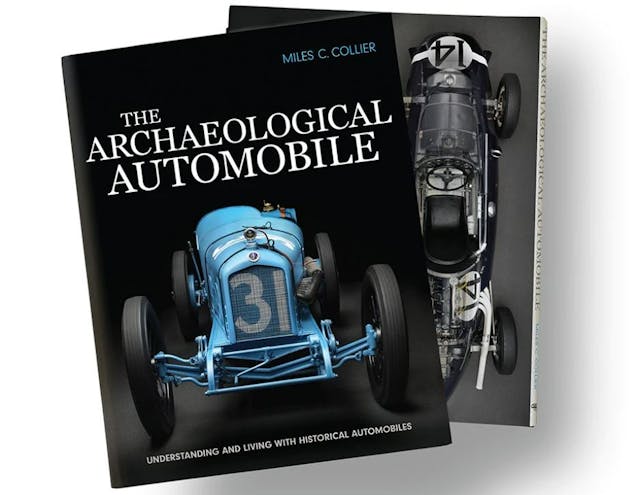

And yet when I received the summons of the Great, I ran to answer. Well, I walked pretty quickly, anyway. I suspect most of you know who Miles Collier is—his family has been part of sports-car racing in the United States from the very first day, and his uncle Sam’s memorial marker can be found on the back straight of the original Watkins Glen course. After a lifetime immersed in the absolute cream of automotive culture and competition, Miles has written a book, The Archaeological Automobile, that purports to set critical and scholarly directions for the car-collecting hobby. An early variant of this book was provided to me for reading and commentary, a job which I addressed with the seriousness and celerity one would apply to any task from “the Great.”

Much of The Archaeological Automobile will befuddle and possibly offend the sort of fellow who has a couple of hastily-restored musclecars stashed in a pole barn. Collier never shies away from discussing the rather astounding privilege of his youth and upbringing in motorsports; he always had the best of everything, ran with the brightest crowd, knew the legendary names on a personal and intimate level. It’s tempting to dismiss the whole book as one-percenter disdain for normal “car guys,” a $150 hardcover equivalent to Paris Hilton blogging a few comments regarding the contents of a mall in Minnesota. Don’t do that. The Archaeological Automobile is a work of authentically original thought and indisputable value, one with application far beyond Pebble Beach or Amelia Island.

Let’s start with the hardest pill of all to swallow: to Collier’s mind, there is a tremendous difference between “collections” and “accumulations.” Most people say they have the former when what they really have is the latter. I’ll use two examples from my, er, “collection” of just over 190 guitars. Since 1982, I have been playing guitars imported by St. Louis Music, or SLM, under the “Electra” brand, and I currently own about 83 of them. I’m not the Electra collector with the most guitars—I’m not even sure I’m in the top five—but I have the world’s most complete collection of “Anniversaries.” In 1981, SLM celebrated its 60th anniversary in business by commissioning 500 (some people say fewer) guitars from Matsumoku of Japan with unique features. One hundred and thirteen of them have been located and catalogued by my fellow hobbyists, and of those 113 I own 18 working examples, as well as four bodies or necks that were removed from Anniversaries between 1982 and today.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

This is a “collection” in the eyes of Miles Collier because I have a specific goal—to collect and restore as many first-rate examples from that limited production run as possible—and because there is an obvious thread running through my choices. The Anniversaries are also commonly acknowledged to be some of the finest Japanese guitars ever made; I would be on less solid ground were I collecting the various crooked junk imported from Japan to the United States during the 1960s and early ’70s, which were notable only for being cheap. Another point: my collection could be realistically “completed” were I to acquire a perfect example of each different Anniversary model.

On the other hand, I’m also a “collector” of Paul Reed Smith guitars, with eight “Private Stock” models, six “Cores,” a few “Signatures” and “Signature Limiteds,” plus a couple of early examples from before “PRS” became a worldwide brand. By Collier’s definition, however, I am merely an “accumulator” of PRS guitars. I just buy and/or commission things I like. There is no common logic running through my choices, nor could my “collection” ever be complete because it has no theme more serious than “cool stuff from Maryland.”

To put it in terms of a pattern-recognition IQ test: If I showed you three of my Electra Anniversaries, you could easily predict what a fourth guitar might be. Showing you three of my PRS guitars wouldn’t narrow it down to anything besides “comes from a certain brand.” So I’m both a collector and an accumulator. Miles sees a lot of value in being the former, and not too much in being the latter. This viewpoint is harsh, it is privileged, it is controversial—but let’s face it: it’s also correct. Accumulators do service only for themselves, while collectors advance the state of the art in a hobby or area of study. Somebody needed to say it.

For the record, I enjoy being an accumulator, and so do many of you, I’d guess. I suspect it’s even possible for an accumulation, pursued long and hard enough, to become a collection after the fact; surely something like this has happened for famous weird-car aficionados Jeff Lane and Myron Vernis, whose eclectic tastes have proven contagious to a whole new generation of automotive enthusiasts. Upon seeing any given car, I can easily predict whether or not either of those gentlemen would find it interesting, despite there being no common thread in their purchases as easy to pull as, say, “Grand Prix winners from 1960 to 1969.”

The bulk of Collier’s book, however, has little to do with the collector/accumulator divide. Rather, it focuses on the scholarly choices that must be made by automotive restorers. For a very long time now, the car-collecting discipline has been split between the competing camps of “make it perfect” and “keep it original,” but Collier is thinking deeper than this basic division. Just for fun, let’s use the 2013 Accord that both Andrew Rains and I ran in Pirelli World Challenge, and that I used to win a NASA regional championship. Let’s say you’re restoring this car 100 years from now. (Why? I can only assume that it’s the only car left on Earth after some catastrophe.) Would you restore it to way it was campaigned by Andrew Rains, who went on to be a pretty big deal in the trackday hobby with his ApexPro device? Or do you restore it to the way it looked for the Watkins Glen race where I won the Optima and VP Fuels awards? Maybe you put a NASA livery on it, to celebrate club racing. Heck, maybe you’re obsessed with 2013 Accords as street cars, so you undo everything and take it back to the way it looked when it left the line in Marysville, Ohio!

These are the questions Miles Collier faces every day in his restoration of vehicles that were campaigned by far more famous people than me or Andrew in races far more prestigious and important than the Pirelli World Challenge. It’s not just liveries or paintjobs. It’s engines, transmissions, gearsets, seats—even the crude vents cut into various irreplaceable race cars over the course of a season to address overheating issues. At first glance, it seems like splitting hairs; who cares if you restore the thing to April 1913 spec or June 1913 spec? Yet once you accept that the restoration of significant automobiles is important, which it is, and that it should be done correctly, which it should, the genuine value of such discussions becomes immediately apparent.

Once the decision to restore a certain way is made, the work is far from over. One must then determine exactly what the car looked like at that time, how it was set up. Sometimes you have photographs or documents that appear to contradict each other. You have five contemporaneous pictures of it, but they are all of the left side. A trusted source wrote something in 1955 that was taken as gospel but which appears to be proven false by a blurry, undercranked film. What do you do then? Reading The Archaeological Automobile will help you understand, and sympathize with, the restorers who have been entrusted with these important decisions.

Although I read an early draft in January, I didn’t fully appreciate Collier’s vision until my son and I took a cross-country trip to visit several aerospace museums from Dayton, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. Time and time again I was confronted with planes in the wrong livery, planes that had been “adjusted” from one specification to another. There was even a Messerschmitt fighter plane that had been painted and equipped in “Battle of Britain” spec—but in reality it had sat out the war in Spain, where it had been delivered in the late ’30s as a completely different variant! At some point, the veneer between “real museums” and the Futurama Museum of Natural History becomes a little thinner than one would like.

The Archaeological Automobile isn’t for everyone, and it’s not exactly a “page-turner” in the traditional sense, but I’m glad Miles Collier wrote it. You can argue that he might be the only person who could have written it, or at least that he is a member of an exceptionally select fraternity with that capacity. His efforts over the years to properly restore important automobiles, and to exhaustively document his guiding principles in doing so, have improved the hobby of car collecting as a whole. For those reasons, and many others, I believe that he will have his own place in history—both as a member of “the Great,” and as someone who achieved greatness in his own right.

Wait a minute. I almost forgot. What’s that car in the photo at the top of this column? Why, it’s a stick-shift Mercury Milan, to replace the one that I bought a while ago. Let’s say I bought a few more of these—maybe sprinkled with a couple of six-speed Fusions. Collection, or accumulation? I leave that for you, the reader, to decide.