Media | Articles

Race cars to respirators: How NASCAR’s Keselowski is joining the fight

Racers all over the world have stepped in to bolster relief efforts and ease the burden on frontline workers during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, often repurposing advanced prototyping and manufacturing equipment typically reserved for building race cars. NASCAR Cup Series driver Brad Keselowski is one such driver and has employed the manufacturing prowess of his company, Keselowski Advanced Manufacturing (KAM), to manufacture dozens of face shields and create molds for hundreds more. We spoke with KAM president John Murray to discover how the ideas came together and what the company has accomplished over the past few weeks.

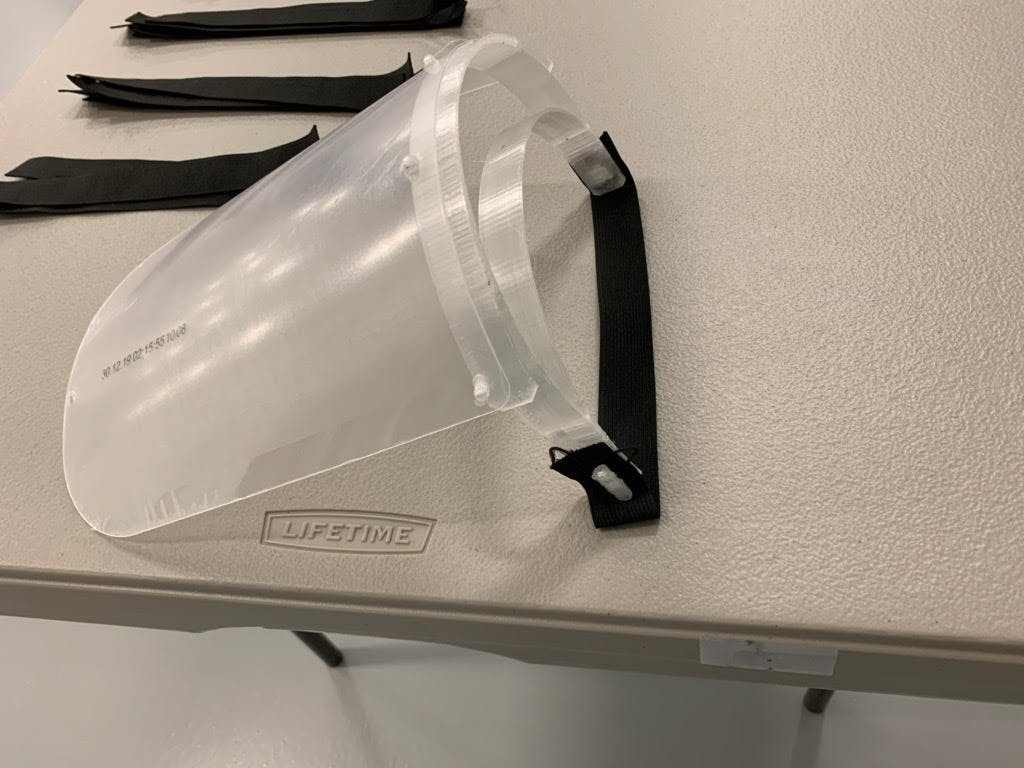

Founded in 2018, Keselowski Advanced Manufacturing’s goal is to use modern prototyping and manufacturing methods, such as 3D printing, to design, build, and test components in short order. KAM’s advantages in manufacturing tech quickly emerged as an asset when calls for pandemic relief efforts began flooding in. Keselowski immediately wanted to invest his company in COVID-19 relief efforts. Following the example of Ford, his team’s manufacturer partner, face shields were the first product put into production.

Although making face shields seems simple, KAM wanted to make sure its products were medically compliant and wouldn’t cause any allergies for potential wearers. So, the company reached out to Shannon Van Deren at Layered Manufacturing and Consulting (LMC) regarding the proper materials and processes. Van Deren was especially suited to advise KAM on this this project because LMC specializes in additive manufacturing for the medical field, among many others.

Following Van Deren’s advice, KAM chose materials fit for the medical community that could be easily sterilized for repeated use. Van Deren didn’t simply help launch the project with proper materials; she wanted to get involved even further and contributed thousands of dollars on her own.

Once the materials and design were finalized, KAM started printing the face shields and has already produced and distributed around 100 of them, with the goal of producing another 400 over the next few weeks. Around half of the initial batch went to the Lewisville Fire Department in North Carolina. In the absence of appropriate protective gear, and before KAM’s shields arrived, first responders in Lewisville had been forced to cover their faces by pulling up their jackets. Van Deren also helped coordinate the delivery of these shields, leveraging her deep knowledge of the medical and first-responder communities to direct the face shields where they were most needed.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Keselowski even brought his Checkered Flag Foundation, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, into the mix. The foundation usually assists enlisted military, veterans, and first responders and is now redoubling its efforts.

While 100 face shields may not seem like an enormous number to begin with, every piece of protective equipment helps. In this case, the quantity of shields KAM can produce is primarily limited by its single plastics-capable 3D-printing machine; KAM’s primary business lies in additive manufacturing of metals. However, though this might seem to limit production, KAM’s prowess in metal manufacturing opened up a novel approach that will boost the face shield production of many third party suppliers.

What started as a goal to print 500 plastic face sheilds turned into printing aluminum molds for face masks. Quite a week @KAMSolutions …

Can you see it? pic.twitter.com/37DirCTblf

— Brad Keselowski (@keselowski) April 10, 2020

KAM’s second project arose when a university asked whether KAM could rapidly build a metal mold for face masks that could be used with respirators. KAM promptly took on the project and used one of its laser metal-printing machines to produce the mold, even fine-tuning the design with the finishing equipment it had on-site.

This mold will now be used by a third party to vacuum-form face masks that can be connected to respirators used by front-line workers. Murray states that KAM “will continue to adapt as needed to support our first responders and medical personnel” by quickly pivoting to projects like this, taking advantage of the wide range of equipment at its disposal. Keselowski added that KAM is “grateful to be able to support our front-line warriors in any way possible.”

Having the capability to 3D-print metal is a distinct advantage. By combining modern and traditional manufacturing techniques—in this case, 3-D printing and mold-making—KAM can work with partners to create equipment in large volume.

When its metal printing equipment isn’t pressed into service for a pandemic, KAM builds some pretty interesting stuff for a wide variety of industries, including racing. Having worked on race teams and seeing the innovation firsthand, we naturally had to ask Murray about at least one of KAM’s projects and how its makes cars even faster.

One of KAM’s recent projects involved optimizing the suspension for a professional-series race car. The company analyzed the original component and found efficiencies in the design using its simulation software; then, the team did prototyping and testing to make sure that the newly improved part would work. Once the team produced a simulated prototype, it transferred the design to one of its metal printers and created the part fairly quickly. Once out of the printer, the component went to the CNC milling machines for fine-tuning before it was delivered to the customer. Although Murray didn’t discuss specifics, due to the highly competitive nature of the racing series and the sensitivity of suspension tech, he said the process was a success. KAM maximized the part’s performance while reducing the weight—a critical balance on race car suspension systems.

Racers have always been a creative group, so it’s great to see that inventive thinking and expertise helping those who need it most. True, we still have some time before we get back to racing. But when we do, take a moment to reflect that the suspension component putting your favorite car out front could have been built on the same machine that built molds for respirators—equipment that’s helping save lives right now.