Media | Articles

Here’s how a ventilator actually works

The cost of the breathing machine most commonly called a mechanical ventilator—hereafter referred to simply as a ventilator—ranges from $25,000–$50,000. But, when the need for one arises, that price tag is the least of your worries.

Ventilators are the hospital’s version of a supercharger. When your breathing is impaired by a COVID-19 infection or other lung-related issue, a ventilator goes to work saving the day. These handy devices automatically fill the lungs with the appropriate mix of air and oxygen with no patient effort required. The oxygen needed to sustain life is delivered to the bloodstream and carbon dioxide is transferred via capillaries into the lungs and out the ventilator’s exhaust port. A patient under duress pants at 30 or so breaths per minute; the ventilator’s inhale/exhale cycle is roughly half that rate and the supply pressure is only a few psi to prevent lung damage.

Ventilators are most commonly found in a hospital’s intensive care unit (ICU) which has ready connections for electrical power and pure, pressurized oxygen. They’re typically rolled to the bedside along with a monitor capable of displaying heart and respiratory rates, blood pressure, and the extent of oxygen saturation in the blood stream.

Roughly the size of a countertop microwave, the ventilator is filled with electronic circuits, computer-controlled valves, and plumbing that delivers the breath of life to one—or, in a pinch, two—patient(s). External knobs and switches allow care providers to regulate the number of breaths per minute, the pressure of the gas that fills the lungs, and other variables. The portable units employed by emergency responders are battery powered and carry their own oxygen supply. Don’t even think about trying to cobble one up at home.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

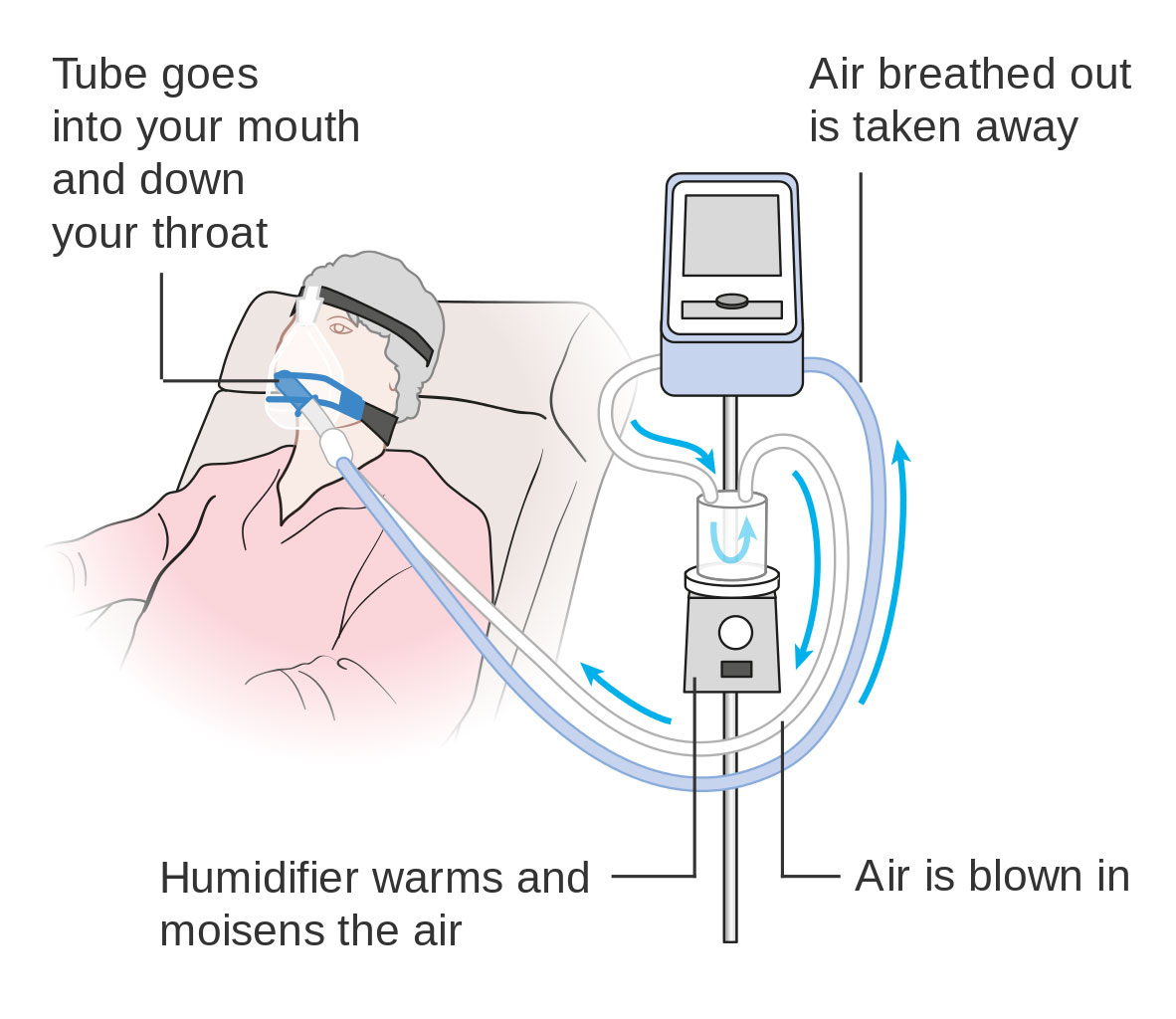

ICU intubation means jamming the ventilator’s delivery cuff several inches down a patient’s throat. That tube is inflated to form a tight seal with the trachea, thereby preventing leakage as well as speaking, eating, drinking, and coughing. Less invasive masks sealed tightly over the nose and mouth are also used. The third choice is a throat incision beneath the larynx (where the vocal cords reside) to provide a ventilator connection without impairing speech. Nutrients are “fed” to the patient intravenously.

It goes without saying the intubation isn’t a time-honored birthday party activity. Patients are typically sedated to let them rest comfortably when mechanical breathing is deemed necessary. The air-oxygen mix delivered to the lungs is automatically moisturized and heated to a comfortable temperature. Along with carbon dioxide, mucus exits the respiratory system on the exhaust stroke.

The nagging question that no one we asked was able to address is “what happens to the presumably germ-laden fluids that a COVID-19 patient exhales?” Our best guesses: Most ICUs operate at negative (less than atmospheric) pressure to move fluids away from patients and caregivers, into the air conditioning system, and out of the building. In emergency and temporary indoor or outdoor settings, natural ventilation carries the nasty fluids up, up, and away. That said, comprehensive personal protective equipment preventing direct contact with an infected patient and ingestion of their bodily fluids is the most important part of every caregiver’s functional wardrobe.

Watching the auto industry rise to the critical need for ventilators cause has been interesting. The government’s goal, according Peter Navarro, Assistant to the President and Director of the Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, is production of 5000 ventilators by the end of April plus another 100,000 by the end of June. Ford is busy rehabbing a Michigan parts plant only a few miles from Hagerty’s Ann Arbor editorial office to team with General Electric in the manufacture of 50,000 units within 100 days.

By mid-April, GM will employee 1000 workers at its cleaned and retooled 2.6-million square foot Kokomo, Indiana, plant to build 10,000 or so units per month in collaboration with ventilator maker Ventec Life Systems of Bothel, Washington. And in a 31,000 square foot Warren, Michigan, facility, GM worked around the clock to begin production of Level 1 surgical masks with the goal of turning out 1.5 million units per month.