Media | Articles

GTO Engineering’s Ferrari 250 GT SWB “Revival” is so much more than a replica

The road cleared at the edge of the village and ran drunkenly towards the horizon. ‘This,’ thought the driver, ‘is my moment.’ In one strong and certain movement he thrust the slender alloy lever forward, expertly nudging the throttle with the well-worn edge of a tasseled loafer, hearing Gioacchino Colombo’s V-12 respond with a crisp bark and, then, that unmistakable Maranello shriek as his foot reapplied the power and, this time, stayed there. The short-wheelbase 250 paused only briefly as it sat down at the back and sniffed the air with its nose of unparalleled beauty. And then it lunged.

Please forgive the gentle pastiche but if you’ve been lucky enough to have spent a day roaming around such roads in a car that looks, sounds, feels, goes and smells like an original Ferrari 250 GT SWB, it’s quite hard when you sit down to write about it not to descend into that style of overdramatic (and doubtless rather hackneyed) prose. It is a car in which dreams are made real in your head, which is probably where they should stay.

The car is the creation of GTO Engineering, the renowned Ferrari specialist near Maidenhead, U.K., founded by Mark Lyon 35 years ago. The idea is that, for around $1 million, this outfit will supply you with a brand-new Ferrari which is as close to a toolroom copy of a 250 SWB as you want it to be, so long as you’re prepared to wait a year to 18 months for it to be built. That is about one tenth the price of a standard, steel-bodied original SWB and perhaps one twentieth the cost of the 1960 competition-specification, alloy-bodied car on which its design is based.

Who would want one? Maybe you’re merely very wealthy rather than lavishly well off, and have worshipped SWBs since you first learned to shift gears. After all, the 1959 model is one of the most notable GT racers of its day, developed by Giotto Bizzarrini, Carlo Chiti and Mauro Forghieri, the same men behind the later 250 GTO.

Or maybe you already own the real deal but dare not drive it because it’s worth so much money and want a replica you can actually use. Or perhaps you’re done with competing with your peers for a place on the list for the next million-dollar hypercar and fancy something gorgeous that can be deployed on the road.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Aside from the time it takes to create (and the fee involved), the only other thing GTO Engineering requires is another Ferrari whose identity the recreation car can adopt. What you’re really after is something from the ‘60s or ‘70s that’s been in a big accident, burned out, or in any other way been put beyond repair. They don’t actually need any parts from the donor car, but if they’re there, correct and in good shape, they could be put to use—you decide.

Within certain defined boundaries, the process offers the customer a great deal of flexibility. It can be built as a road car or as a racing car complete with FIA papers indicating its specification is true to that of the original, and that will get you onto most grids and into most events. To be fair, though, perhaps not all. The original car came with a 3.0-liter V-12. In reality, customers almost always go for the 3.5-liter or 4-liter upgrade for their additional power and torque, but both are externally indistinguishable from the original. You can have a four or five-speed gearbox, but it will still be to 60 year Ferrari specification—not something generic plucked from the shelves of Quaife, Xtrac, or Hewland.

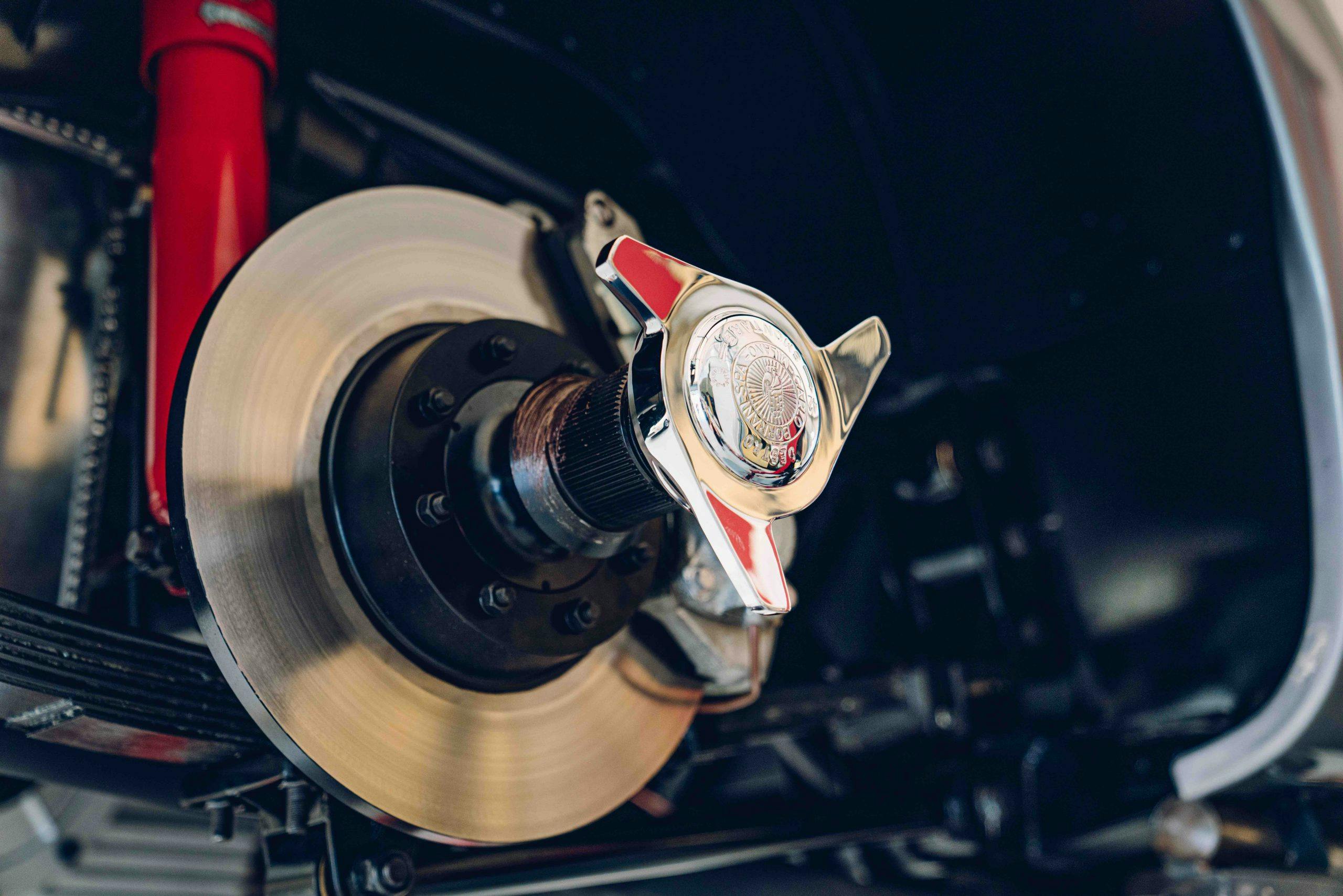

There are some key differences between an original and this recreation. GTO will fit air conditioning if asked (though Mark Lyon doesn’t like it because it’s hard to hide under the hood) and unless you really object it will come with slightly different spring rates and damper settings, because development in such areas has advanced somewhat over the last 60 years. But except for such details (and the fact it will be rather better built) it really is a 1960 competition Ferrari 250 GT Short Wheelbase in all but name, for a 95 percent discount. Which sounds reasonable to me.

The car I drove had the mid-spec 3.5-liter engine, offering an easy 320 hp for fast road use, over a power band that starts in earnest at around 2500 rpm and was still hauling hard when I ran out of nerve at 7500 rpm. Properly built, these Colombo engines are almost indestructible and it’s probably safe past 8000 rpm, but I didn’t fancy pushing my luck quite that far.

It is incredibly easy to drive. Power steering is something else GTO would consider adding but the car really doesn’t need it: with that large, elegant wood-rimmed wheel and quite low gearing, the Ferrari is remarkably light to maneuver, thanks to its relatively skinny tires and curb weight of just over 2240 pounds.

When driving it from cold, you ease into the opening miles slowly. Like all old Ferraris you not only have to take your time because it takes an age for the oil to warm up sufficiently to register on the gauge, but you want to as well. There’s much to appreciate.

The view down the hood is one of the greatest a driver can enjoy, and then there’s the one across the dashboard that takes in the platoon of Veglia dials. It’s so simple yet so elegant in here, such a contrast to the gratuitously indulgent and complex cabins of modern supercars in general. Ferraris in particular. In the SWB if you need it, it’s there, easy to find and operate. If you don’t it’s not.

Other things you notice are the ride quality, which is far better than you’d imagine it might be for a car of this kind with a leaf-sprung live rear axle. It’s compliant and comfortable while noise levels are perfectly reasonable. With a decent-size trunk, you begin to realize that this is a car in which you could really go places. The South of France for instance. Before you’ve put your foot to the floor even once, you’re starting to dream …

I have to make do with southeast England’s Home Counties, where there are still some excellent roads if you know where to find them. Then, when the road really does clear and you’re finally able to let this extraordinary machine off the leash, it really is quite difficult to avoid descending into the self-parody escapist dream I indulged in earlier, because you really are in a V-12 Ferrari built to that specification and this really is a magical experience.

The first surprise is just how damn rapid the thing is. Because it’s based on a 60-year old design and doesn’t have an enormous engine, in your head this is going to a fast car but hardly feral. Think again or, better, do the math and discover approximately the same power to weight ratio as the most recent Porsche 911 GT3, making GTO’s handiwork up there with quickest cars on the road.

Even so, that’s not what this car is about. It’s about the sensations of feeling the road through the superbly sensitive steering and wonderfully communicative chassis. It’s the perfect weighting and precision of the gear changes. It’s the sound of that insanely brilliant engine and the balance of a chassis developed to a fine pitch by Ferrari through the 1950s and further still by GTO Engineering.

I’ve been doing this for a while and am really quite picky these days, and I can’t really think of what I’d want to change on this car.

I’d not even go for the full-fat 4-liter because the 3.5 feels so right for the chassis. You can pitch it into a corner on a trailing throttle, feel the back start to drift, and then use the power to arrest the slide even before your hands have returned to the straight ahead position. Traction is remarkable when the car is driven like this, though were I on a track I know it would just drift and drift and drift. No wonder racing drivers like Stirling Moss (who won two RAC Tourist Trophy races in consecutive years in 250 SWBs) just loved driving these things: they were the fastest cars of their kind, almost never broke, and were simply brilliant fun.

Of course some will carp, say it’s not a proper SWB and point to all the other entirely original and still quite exotic Ferraris this kind of money can buy. You can, and if that’s what you want to do, good luck. But that doesn’t make those cars right any more than it makes this car wrong. It’s not an original SWB and doesn’t pretend to be. It doesn’t have that history and there is undeniably a dimension we call provenance that’s missing. It is nevertheless a beautiful hand-crafted creation and one of the finest things I’ve driven on a public road in over 30 years of doing this job.

Did GTO Engineering have to enter into a licensing agreement with Ferrari to legally reproduce these cars?