Media | Articles

Edsel’s Fords finally come home

Henry and Clara Ford had only one child, their son Edsel, whom Henry alternately doted on and kept under his thumb. Henry made Edsel president of Ford Motor Company in 1919, when Edsel was just 25 years old, but he personally destroyed the prototype when Edsel tried to restyle the Model T. It took years for Edsel to convince his father to put hydraulic, rather than mechanical, brakes on Ford automobiles. Despite Henry’s interference, the senior Ford had little interest in design, which gave Edsel enough space to become one of the fathers of automotive styling. While he never personally styled a production car—instead relying on the talent of Eugene T. “Bob” Gregorie, the first head of styling for Ford Motor Company, to render his ideas—Edsel Ford was no novice at the visual arts. He himself drew and took painting classes his entire life, and Edsel and his wife, Eleanor, were informed patrons of the arts. Edsel underwrote the creation of the renowned Detroit Industry murals that Diego Rivera painted in the great hall of the Detroit Institute of Art, and Eleanor donated and funded that museum’s multi-million dollar collection of African art.

As mentioned, Edsel Ford had a close working relationship with Gregorie, and Edsel liked to spend time in the styling studio offering suggestions and approving designs. Their relationship went beyond work on production Fords and Lincolns (Henry having bought Lincoln out of Henry Leland’s bankruptcy, it has been said, to give Edsel something to play with). It was to Gregorie that Edsel turned when he wanted to express his personal taste in automobiles. Working together, the two men created three of the most influential automobiles ever, two custom Ford speedsters and the 1939 Lincoln Continental. In terms of styling, one could argue that only landmark designs like the 1948 Cisitalia have been as influential as Edsel’s personal cars.

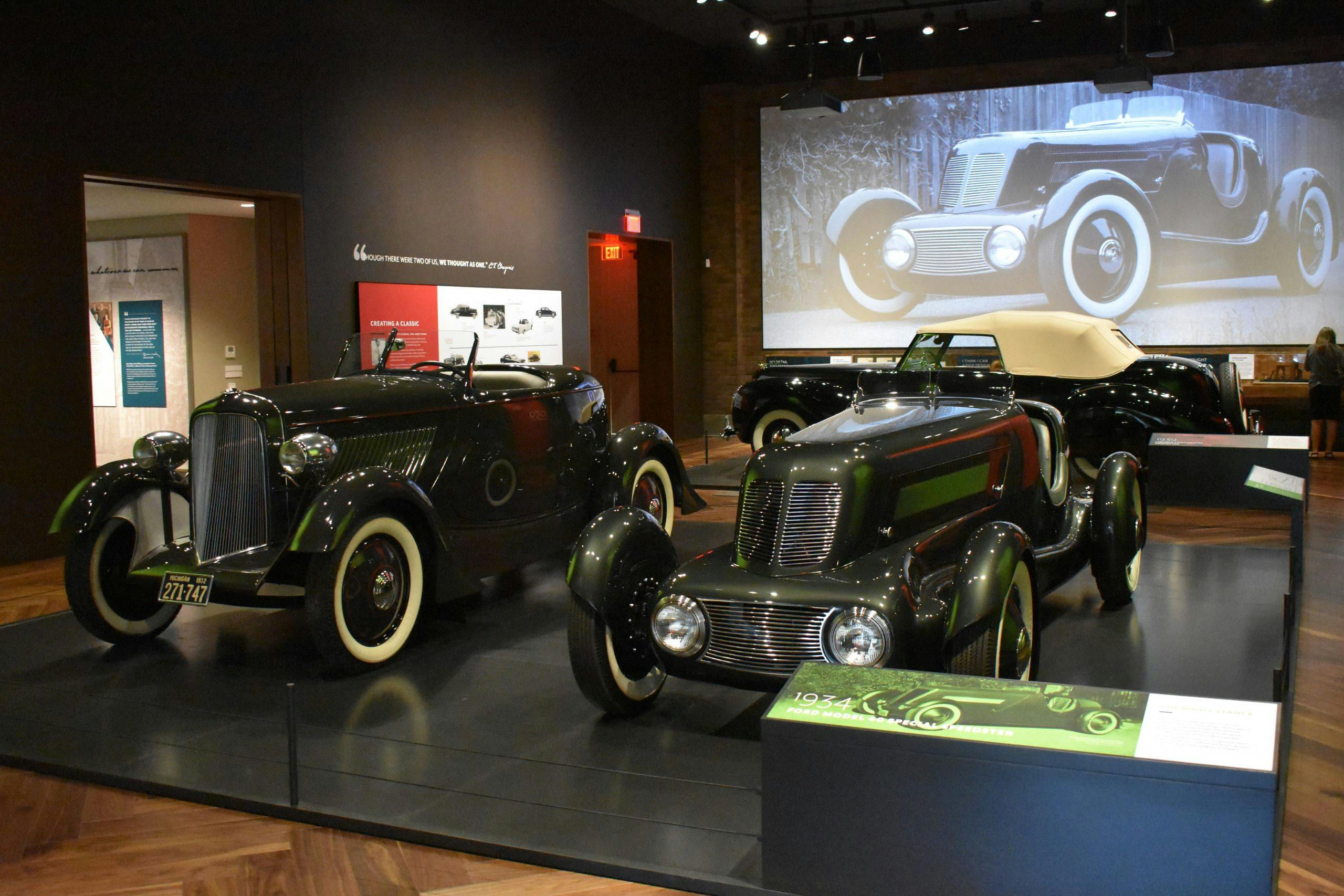

For the first time ever, Edsel’s cars have come home, and you can see them in their native environment. After a year’s delay due to the pandemic, the Ford House, Edsel and Eleanor’s estate, has opened up its comprehensive visitors center, where the three cars are now in a permanent exhibit titled Driven by Design. Though the Ford House has owned all three vehicles for some time, for the most part they have been on loan to other institutions and car shows. They are now together for the first time.

By the mid 1920s, due to the success of the Model T, the Fords were one of the wealthiest families on Earth. Befitting an industrial prince and his princess (Eleanor was, in part, raised by her uncle J.L. Hudson, who owned Detroit’s major department store), Edsel hired architect Albert Kahn, who designed Ford Motor Company factories, to design a Tudor mansion on Gaukler Point, a beautiful piece of land that juts out into Lake St. Clair, just north of the wealthy Detroit suburb of Grosse Pointe. Edsel and Eleanor furnished it with authentic fittings imported from the Cotswolds in the U.K. and moved into their new home in 1929.

The waterfront location accommodated Edsel’s interest in boats, a fashionable hobby among Detroit’s elite which Edsel could also enjoy at his family’s vacation homes in Seal Harbor, Maine, and Palm Beach, Florida. Edsel shared that interest in boats with Gregorie, who had first worked as a yacht designer before stints at coachbuilder Brewster & Company and at Harley Earl’s Art & Colour studio at General Motors. In 1935, Edsel promoted Gregorie to become Ford’s first styling chief, leading a small team of designers.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The two men had already been collaborating for years before Ford had an official styling department. Gregorie had a talent for visualizing Edsel’s ideas, the artistic skill to render those ideas, and the technical skill to translate those two-dimensional drawings into three-dimensional shapes. In 1932, when Edsel returned from a trip to Europe, he asked Gregorie to design and build him a “sports car” like those he’d seen “on the continent,” something “long, low, and rakish.”

This was a little more than two years after the 1929 stock market crash that set off the Great Depression. Lincoln’s Detroit plant was mostly idle, and production of the Ford Trimotor airplane was winding down. Gregorie was able to use Lincoln to build much of the Speedster, crediting plant manager Robbie Robinson with much of the work on the chassis. The body was hand shaped of aluminum by craftsmen at the aircraft division.

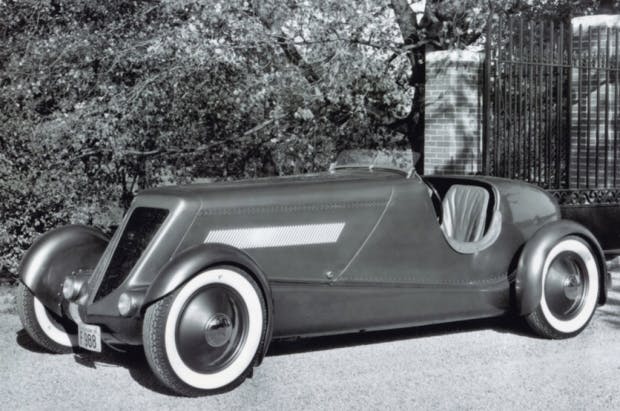

Starting with the 1932 Model 18 Ford, Gregorie penned a boattailed speedster body that visually stretched the Model 18’s relatively short 106-inch wheelbase. He lengthened the stock ’32 Ford’s hood, extending all the way to the windshield, adding a couple of cooling vents. Some sources say that the rakishly tapered fenders were modified Trimotor aircraft “wheel spats,” but others say they were fabricated from scratch. The bottom of the radiator grille was vee’d forward, presaging the grille on the 1933 Ford, as did the Speedster’s slanted hood louvers and suicide doors. Anticipating, or perhaps inspiring, “shaved” hot rods, Edsel’s ’32 Speedster has no exterior door handles. The windshield was raked and pointed, predating trends that would appear later in California customs. The clean, streamlined look was accentuated by deleting bumpers and running boards, and aluminum was used liberally—in the spun wheel covers and distinctive, polished-aluminum, bullet-shaped headlights, another feature that would show up on later hot rods. A pure Speedster, it had no top.

Edsel would occasionally drive the ’32 Speedster from his home to work in Dearborn, eventually fitting it with an updated 221-cubic-inch flathead Ford V-8 engine for better performance. Back then, before expressways, the drive would have taken at least an hour, so Edsel must have liked the car.

Despite the fact that he liked it, Edsel and Gregorie discussed making an even lower and racier speedster. Gregorie started work on the new car and Edsel sold the ’32 Speedster to a Grosse Pointe neighbor named Elmer Benzin, who then sold it to a GM designer, who crashed it. For a long time it was thought to have been scrapped, but in reality the wreck ended up in a Bridgeport, Connecticut, junk shop. A body man, John Cox, bought it and repaired the damage using fenders from a 1935–36 Chevrolet and a stock, flat Ford grille shell. He sold the car soon after.

More than 40 years later, in the mid-1980s, Cox spotted the car. He recognized it and bought it back, hoping to restore it—still unaware of its history with Edsel Ford. He only got as far as disassembling it when neighbor James Gombos caught the bug and kept asking Cox to sell it to him. Cox never did, but after his death in the mid-2000s, his family sold the car to Gombos, who later told Hemmings, “There wasn’t much to it when I got it. It was all apart. All the body from the firewall back was there, but there were no fenders, grille, or hood.”

Gombos started a painstaking five-year restoration using period photographs to reproduce custom parts that had gone missing over the years. Mike and Jim Barillaro from Knoxville, Tennessee, hand-crafted new aluminum fenders, and the car was painted in 1932 Ford Tunis Gray—based on untouched paint that Gombos found on the underside of the cowl vent. The interior was upholstered in dark gray-brown leather. A period-correct ’36 flathead Ford flathead V-8, with a Stromberg 81 two-barrel carburetor, was sourced to power the Speedster.

The Ford House bought that car for $770,000 at Amelia Island in 2016, a record for a 1932 Ford, although it didn’t reach the presale estimate of $1 million or more.

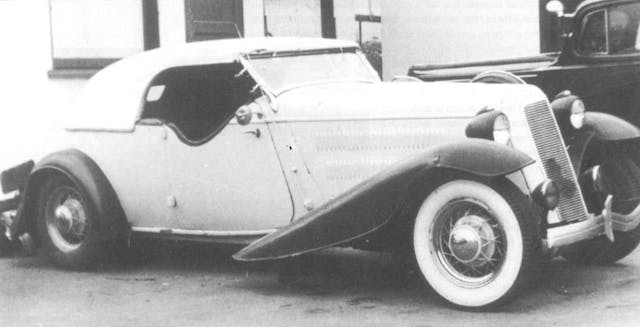

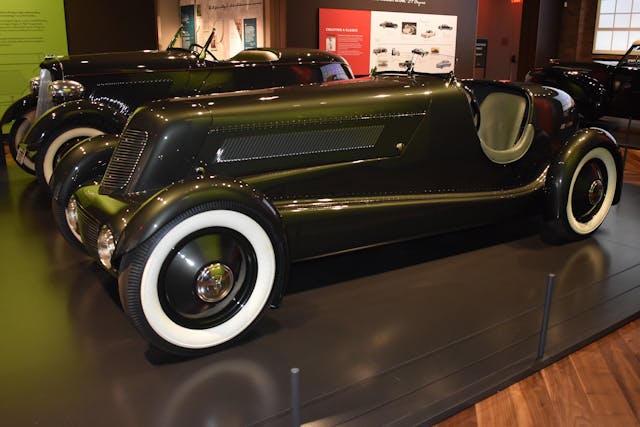

As innovative as Edsel’s 1932 Speedster was, it was still quite obviously based on the ’32 Ford. For their next project, Edsel wanted Bob Gregorie to build him something even more radical, something streamlined. After Gregorie presented Edsel with several sketches, Gregorie fabricated a 1:25-scale model of the sketch that Edsel approved, and he tested it in a wind tunnel at Ford Aviation’s Air Frame building, making it one of the first cars to be designed using a wind tunnel. The proposed car was long and low, much lower than the ’32 Speedster.

Gregorie started with a 1934 Model 40. To be able to significantly lower the car, he flipped the rear frame’s kick-up upside down, so the frame rails passed below the back axle, allowing for a six-inch drop. The front axle was moved forward 10 inches, and a combination of stock and custom suspension and steering parts were used to lower and extend the front end.

The body was again fabricated at the aircraft division per Gregorie’s design for a two-passenger roadster, with a vee’d grille; a tapered, boattail rear end; and cut-down doors. The hand-formed aluminum panels were mounted to a tube framework. Again, the sources say the cycle-style front fenders that turn with the wheels were modified from Ford Trimotor parts. Stock Ford wire wheels got custom wheel discs. The finished car weighed only 2400 pounds, so the stock 75-horsepower Model 40 flathead V-8 still gave it sprightly acceleration with a three-speed manual transmission and a floor shifter. Edsel apparently favored shades of gray; the new speedster was finished in Pearl Essence Gunmetal dark gray that looks green in some lighting. The interior had custom gray-leather bucket seats and an elegant engine-turned aluminum dashboard. Straight exhausts exited the car at the rear, passing through a section of the frame on their way there.

The ’34 Speedster is the definition of coherent design, and wouldn’t look out of place on a 1930s-era race track. Another pure speedster, in order to maintain the low look, it had no provisions for a roof, but then Edsel only drove it on sunny days, often in Florida. The grille, windscreen, and hood louvers are all at the same rakish angle. As with the ’32 Speedster, there are no running boards. A valence panel, attached to the body with precisely spaced, aircraft-style rivets, covers the frame as it gently curves from front to back. The car’s remarkably low proportions are accentuated by cut-down Brooklands-style racing windscreens. The radiator was fully enclosed in the bodywork, which featured small, low-mounted headlights that were faired in to the sheetmetal. There was a noticeable absence of brightwork. Edsel titled the car in his own name. He was so happy with it that he and Gregorie discussed the possibility of selling it as a limited-production performance Ford.

How seriously Edsel considered producing it is open to speculation as he still feared his father’s wrath based on what happened to that Model T prototype. When he wasn’t driving it in Palm Beach, like his ’32 Speedster he stored it at Gaukler Point, nowhere near his father’s stomping grounds in Dearborn. Sources say it was kept in an unheated “shed,” but the estate has a carriage house bigger than most people’s entire homes. Either way, a deep freeze in the winter of 1939–40 cracked the engine block, so a then-new 1940 Mercury V-8 was swapped in. A later owner would replace that engine with a NOS 1940 Ford V-8, with dual carburetors and dual exhausts. The Mercury engine, although removed, remained with the Speedster.

Edsel found out that as good as the front end looked, some of the sheetmetal partially blocked air flow to the radiator, and the engine would overheat in the Florida sun. Gregorie shortened the vertical grille, added a lower, horizontal grille that echoed his design for the ’39 Continental, and flanked the lower grille with two large headlights. The result is visually arresting, if not quite as elegant as the first iteration. Gregorie made a scale model, and its photo, with Edsel Ford’s handwritten approval, still exists.

Edsel Ford died of stomach cancer in 1943. Surprisingly for an auto magnate, he had just six cars in his estate, the ’34 Speedster being one of them. It ended up in Atlanta, Georgia, where it changed hands for $1000. In 1947, the owner shipped it to Los Angeles, and the following year a classified ad in the May 1948 issue of Road & Track read, “Especially constructed Ford chassis. Aluminum body built for Edsel Ford. Now powered with special Mercury Engine. Priced reasonably at $2500. COACHCRAFT, LTD, 86 Melrose Ave, Los Angeles, California.”

Apparently the Speedster didn’t sell, and in 1957 it was returned to Georgia. A year later John Pallasch, a sailor in the U.S. Navy, bought it at a used car lot in Pensacola for $603 and drove it to his home in Deland, Florida. By then the car was red with a red interior. Pallasch drove it for a couple of years before taking it apart in preparation of rebuilding the engine, but he then shipped out to Vietnam, leaving the car in pieces. By the time Pallasch returned stateside in the late ’60s the engine had seized up. The car then remained disassembled and in storage for almost four decades.

In 1999, Bill Warner, founder of the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, was trying to track down the Edsel Speedster to display at the concours. A Michael Lamm story about Edsel’s speedsters that was published in Special Interest Autos magazine indicated that the car was owned by an Earl Pallasch in Deland, Florida. Unable to find anyone named Earl Pallasch, Warner contacted Lamm, who gave him contact information for John, Earl’s son. Warner called John Pallasch and invited him to show the car at the Amelia Island show. Pallasch told him that it wasn’t in running condition and that he really wanted to sell it. Warner hitched up his trailer and grabbed his checkbook. He found the Speedster in Pallasch’s garage, covered in decades of dust and junk, but it was essentially complete save for missing the custom wheel discs.

Warner wrote a check on the spot. On his way home he passed through St. Augustine, where Bob Gregorie, then 91, was living. “I called Mr. Gregorie and asked if I could drop by. I said I had something I wanted to show him. Mr. Gregorie came out of his house, smiled, and ran his hands over the surface of the car. ‘I haven’t seen it since 1940,’ he said. ‘The old girl still looks pretty good for her age.'”

Warner considered doing a full restoration back to the original grille design, but in the end decided the speedster was a piece of history. Instead he and his team rebuilt the engine, replacing the aftermarket Edelbrok heads that had likely been installed when the car was in Hollywood with stock units, and then touched up the paint. Al LaMarr fabricated new wheel discs.

Warner sold the ’34 Speedster for $1,760,000 RM’s 2008 Amelia Island auction. In 2010, the organization that operates the Eleanor and Edsel Ford estate, now branded Ford House, announced that it had acquired the car and sent it to RM Restorations in Ontario for a year-long restoration.

Ironically, other than for a few publicity shots taken on the grounds of the estate when it was freshly restored, the ’34 Speedster hasn’t been there in 10 years, spending the past decade on tour to various concours, car shows, and museums.

Now it is back home with its sibling, the ’32 Model 18 Speedster, and its cousin, the 1939 Lincoln Continental prototype.

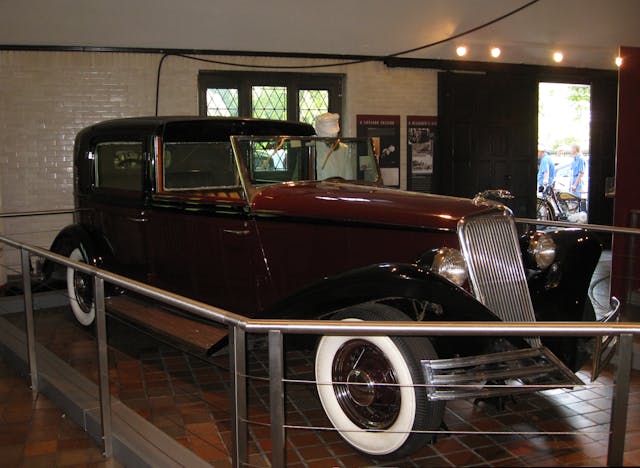

In addition to the three cars on display in Driven by Design, the Ford House collection of vehicles includes Eleanor Ford’s personal 1934 Brewster Ford town car, which Edsel Ford designed himself, one of 13 Fords that were bodied by Brewster and the only one without Brewster’s own heart-shaped radiator grille. Other Ford family cars owned by the Ford House are Edsel’s custom 1930 Ford Model A dual cowl phaeton by Le Baron, built on an experimental European Ford chassis; a 1938 Lincoln Model K with a Brougham body by Brunn, perhaps Edsel Ford’s favorite coachbuilder; a 1939 Ford Woody station wagon (it’s not generally known, but it was Edsel Ford who originated the idea of a “woody” with his custom-bodied 1928 Ford Model A depot hack); and a custom 1952 Lincoln town car that Derham built for Eleanor’s use, with a raised roof so she didn’t have to remove her hats. Because of the close relationship between the Ford House and The Henry Ford institutions, over the years the Ford House has also been able to display other Ford family cars that are in the collection of the Henry Ford Museum, such as Edsel’s personal 1941 Lincoln Continental.

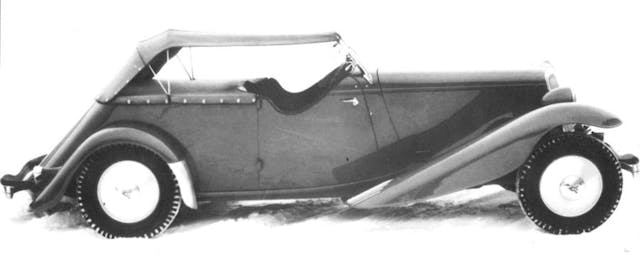

There was actually a third sports car that Bob Gregorie developed with Edsel Ford, the 1935 Special Sports. Unlike the two speedsters, this was a four-seater actually intended for limited production. Ford and Gregorie wanted to make a longer and lower version of the stock Ford passenger car chassis to sell to coachbuilders who would make custom bodies for it. Gregorie sketched a placeholding body, and even drove the barely finished open car (for a change, this had a roof, but it didn’t have working heat) through a snowstorm to New York City to pitch it to Brewster but it, along with other domestic body coachbuilders, passed on the project.

While the body that Gregorie designed for the ’35 Special Sports was intended simply as a placeholder, it’s an attractive design with cutaway doors and could be mistaken for something along the lines of an MG TC. I’m not saying that it influenced English sports cars such as the MG or Jaguar SS100, but it wouldn’t look out of place with them.

As it happened, Ford and Gregorie found more success in the U.K., where from 1936–39 Jensen Motors Limited built several dozen 3.5-liter speedsters very similar to Ford and Gregorie’s mule, using essentially the same chassis design that Gregorie worked out for the third Edsel Ford speedster. There are photos of the car, so theoretically a replica could be created based on one of those Jensens.

Edsel Ford gave the third speedster to Gregorie, who drove it for a few years before selling it to a friend on Long Island. Since then, it has only popped up once. A 1952 photo shows it on a used car lot in Burbank, California. It had been modified, with a LaSalle grille, a padded “Carson” top, and a two-tone color scheme. It has been lost to history ever since.

Of course, there was a time when both the 1932 and ’34 Edsel Ford Speedsters were also thought to be lost to history. Thankfully they have not, and you can see them together with the ’39 Continental prototype. The Ford House and its new Visitor Center are open Sundays from 9 a.m.–5 p.m., and Tuesday through Saturday, 10 a.m.–8 p.m.

I ask about new on the 2024 edsel. All I get is old news about the failed edsel from late 1950’s. What’s up?