Media | Articles

What It’s Like to Race an NHRA Funny Car in 2024

When Ron Capps inches his Funny Car towards the staging beam that sets the Christmas tree that signals the start of the race, he can’t see the track. Swaddled in layers of Nomex, his view is entirely blocked by the injector of the roots supercharger that sits atop the 8.19-liter, 12,000-horsepower V-8 that’s quaking and churning just ahead of his feet.

When the lights on the tree flash yellow, Capps releases the hand-operated brake and mashes the throttle. His Funny Car squats for a moment, wheels twisting so hard they wrinkle the massive sidewalls of the 16-inch-wide, 36-inch-tall tires. Then the car explodes forward.

As the speed increases, centrifugal force causes the tires to expand to an even greater height. Finally, more than halfway down the run, Capps can see the finish line. It’s about here that the multi-stage clutch fully engages, delivering all 12,000 horsepower through those now-taller tires and pushing Capps’ Funny Car, a caricature of a Toyota Supra, past 300 mph.

The car is approaching terminal velocity, pulling Capps so hard he needs straps to keep his helmet from flying back. As the car nears half the speed of sound, the sound starts to play tricks on the driver’s brain: The world goes quiet.

The experience, Capps says, is like entering hyperspace in an old sci-fi movie. “It’s like the world’s coming apart, and you’re being shot into a time machine… In my rookie year, it took me a dozen runs because I thought something was wrong with the car. My crew chief said, ‘No, nothing’s wrong. It’s just starting to run.’ I went, ‘Oh my God, what am I in for?'”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

At that point in the run, he’s in for a concussing return to reality. That acoustic diminution lasts an instant before Capps releases the chutes and crosses the finish line. As that sound washes back over him, and the chutes blossom, he’s immediately thrown from six gs of acceleration to over nine negative gs. Imagine a 60-pound weight pulling your head back that’s instantly replaced with a 90-pound weight snapping it forward, and you have some idea of the violence that Capps goes through on every run. As he puts it:

“Most people would shit themselves.”

I spent hours with Capps and his team, Ron Capps Motorsports, at the New England Nationals in Epping, New Hampshire, and he isn’t someone who uses much profanity. Capps, a three-time NHRA Funny Car champion with 76 career wins to his name, recently celebrated his thirtieth anniversary of running Top Fuel. He started as a mechanic, toiling for years before ultimately getting a chance to drive.

“I was a crew member. I didn’t have wealthy parents or a sponsor I could bring,” he says. But, with a father who raced at a local strip in California, he knew his way around the industry and eventually earned himself a shot behind the wheel of a dragster.

“I worked on them, and I’d been around them so often that when I got in, it felt like I’d already done it.”

In his test run, Capps actually went faster than the team’s driver. He was offered a chance to drive the race car—but only if he drove the truck, too, continuing to wrench and even to handle whatever odd jobs needed handling. Capps eventually worked his way up to earn a seat in a Top Fuel dragster, where he was noticed and ultimately hired by Don Prudhomme, one of the greatest legends in drag racing.

The storied sport has evolved immensely over the years in the pursuit of getting from one end of a drag strip to another as quickly as possible. Though safety now dictates a shorter run for the top classes—1000 feet instead of the traditional quarter-mile, as of 2008—NHRA’s nitro-powered classes now post higher trap speeds than they did in the quarter. They do so despite running the same basic engine configuration as before, a 500-cubic-inch V-8 that sits either ahead of the driver, in a Funny Car, or behind them, in the long, needle-thin Top Fuel dragsters. Funny Car engines receive longer headers to clear the oddly proportioned bodywork that earned the class its name. The camshafts are likewise different, but otherwise, the motors are effectively the same.

“If we were hurting, we could probably borrow one and put that right in our car,” Capps says, gesturing toward one of the motors from the NHRA Top Fuel dragster of Tony Schumacher, sitting on the other end of a shared hospitality area.

But despite the similar powerplant and the noxious nitromethane fuel, driving a Funny Car is nothing like driving a Top Fuel dragster. Dragsters, with their 300-inch wheelbases, are like a “trail ride” compared to a 125-inch wheelbase Funny Car, Capps says.

“It is about as evil, as unpredictable as you can get. I’ve gotten to drive sprint cars, midgets … I’ve gotten to race a lot of different stuff, and there’s nothing like it,” he said. It’s this extra level of involvement that’s the thrill for him.

A surprising amount of the outright performance of the car lies not in the hands and feet of the driver but in the skill and expertise of the crew chief. Virtually every form of motorsport relies on both man and machine, but in the NHRA’s nitro-powered drag racing, the crew chief has more of a say than most in the day’s performance. For Capps, that chief is Dean Antonelli, who has decades of experience in the sport.

Antonelli’s office is located at the front of one of trailers that Ron Capps Motorsports brings to the races. It is full of displays, like the pit wall at many motorsports events. He has no shortage of telemetry at his disposal—up to 80 channels’ worth on the car, covering everything from ride height to tire temperature. This is far from unusual in modern motorsports, but how Antonelli uses that data is. In other top forms of motorsports, like Formula 1, you’ll see engineers agonizing over real-time feeds streaming off of cars, making decisions for setup and tire changes. That can’t happen in drag racing.

“Live telemetry won’t work in our sport because by the time you recognize what’s happened, it’s over,” Antonelli said.

Antonelli’s job is to predict what will happen on a run, of which Capps might get fewer than a dozen in a weekend. That’s less than a minute of running at speed, and the tiniest of imperfections can ruin everything.

To start, Antonelli agonizes over the topography of the drag strip. A modern strip at a premiere venue like New England Dragway is astonishingly flat, but on smaller tracks, the variations can be significant.

He pulled up telemetry from a previous run from the track in Gainesville, Florida, displaying the ride height of Capps’ Funny Car over a single run. Toyota provides its teams with a scan that shows variations in height down to the thousandths of an inch. “The worst deviation on that track is 150 thousandths over 15 feet, and that makes the car go three-quarters of an inch,” Antonelli says. “It upsets the car.”

Another key piece of data is the weather. Temperature and air pressure are critical, as is humidity. NHRA engineers rely on a measurement called grains, which is effectively the volume of water particles in a cubic foot of air.

This measurement is so important to the tune of the engine that Antonelli gets updates on current readings every minute, delivered in a very old-school way: a pager. The beat-up unit only leaves his hip when he’s sitting at his desk.

“I can have [the data] go to my phone, but the software for that [supports] only five-minute updates. My pager updates every minute,” he says.

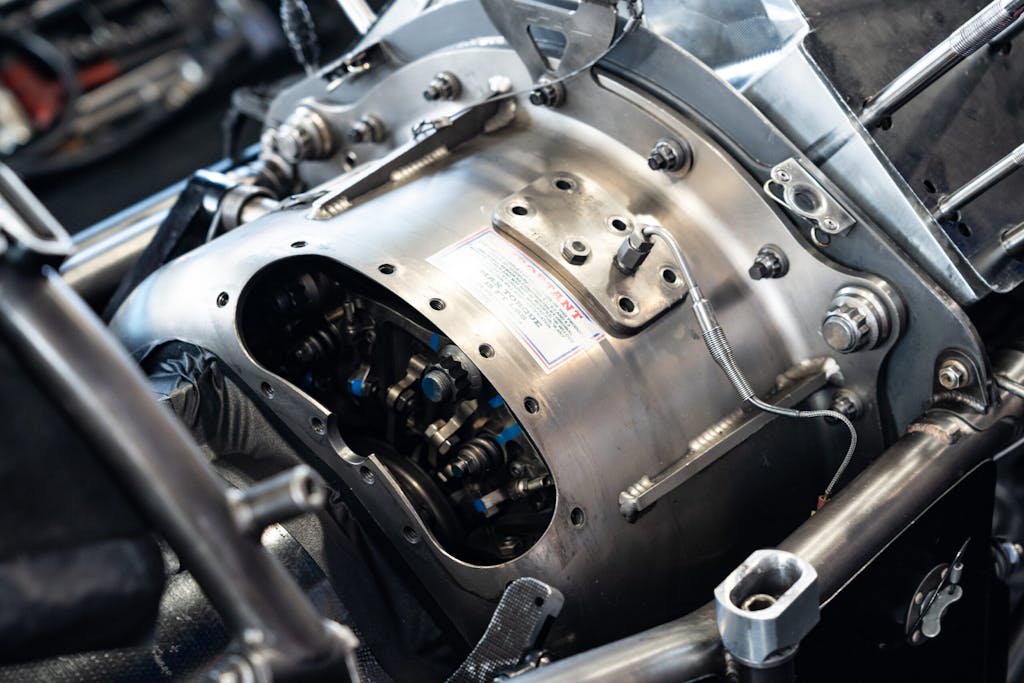

Grains and air pressure help dictate things like engine timing and compression ratio, but even if the tune is completely wrong, Capps’ car will still deliver enough twist to light up both of those massive rear tires. That’s where perhaps the most critical aspect of the setup comes in: the clutch.

If you drag race a manual car, you’ll need a little finesse on the left pedal to get things moving quickly without spinning your tires, bogging down your engine, or sending your clutch up in a cloud of pungent smoke.

In the nitro-powered NHRA classes, the clutch is an integral part of traction throughout the run. It’s used to modulate the torque transmitted to the tires and, therefore, the amount of grip they demand from the track. Antonelli sets up a detailed mapping of how much pressure should be applied to the clutch fingers at certain points during the run.

He relies on reams of data from prior runs and ambient conditions to determine how much torque to allow and at what time. He uses this information to create a precise, preprogrammed digital map that is uploaded to Capps’ Funny Car before the run. There’s no traction control allowed, no smarts in the system, so Antonelli’s estimates must be perfect. Grip is another component of his calculations, and team engineers are constantly measuring it using a series of devices that determine the coefficient of friction. But, for Antonelli, intuition still has a place.

“There’s no replacement for data, but there are still some aspects of feel and gut,” he says. “I can go out there, look at their data, look at our torque meters or coefficient gauges, and I can go up there and walk the track and say, ‘Yep, it’s got a lot of grip, it’s sticking, but it’s got a lot of give.'” His observations might result in a softer clutch setting just moments before the run.

As you can imagine, massive strain is put on the clutch, which is made up of six plates of a design initially used on a John Deere tractor. Teams mix and match new plates for each run. Antonelli prefers to use three new to three old. Each plate will survive only two runs. The lives of parts are generally short, with wrist-thick connecting rods lasting an average of seven runs each. Pistons are good for between two and four, a crankshaft for 12. A short-block might last 60, but all the sleeves get pulled and inspected after every run. Antonelli’s crew of nine, counting himself and his assistant crew chief, can tear down and rebuild a Funny Car in under an hour.

Those nine people are here for one reason: to hurl Capps and his Supra 1000 feet further into the state of New Hampshire in somewhere around 3.8 seconds. At the New England Nationals, held the first weekend of June, Capps never quite got there, struggling to find grip through evolving track conditions. This included one run where a competitor dumped a load of fuel right at the line right before them.

Antonelli takes a moment to consider his words. “I would have liked to have had another car between us,” he says.

Capps ran a 4.045 at 324 mph on Sunday to advance into the quarter-finals, but he was eliminated in the next run.

The competition is getting stronger every weekend. “Somehow, it’s tougher every year,” he said. But the competition is not just tougher—it’s younger, too. Capps turns 59 later this month, while Daniel Wilkerson, the driver who eliminated him that Sunday, is 36. There’s no shortage of younger guns aiming for greatness in NHRA’s many feeder classes.

“Kids are coming up with their lightning-fast reactions that I had back then when I was that age. I’ve got to fight for it now,” he says. “But consistency outdoes that. If you’re a better driver, you find ways to be consistent.”

“Hopefully,” he adds.

If he can prove his consistency, Capps has plenty of reason to hope for a long career in the series. John Force, who won the New England Nats and is the winningest driver in the NHRA, recently turned 75.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

A good crew chief is the difference between winning and losing.

But a funny car driver still needs to drive. Unlike top fuel the cars dance around much and it takes a quick and accurate hand to keep it straight. Top fuel is more forgiving.

I got a kick out of Tony Stewart’s first impressions. His mind is still catching up to the run. It starts and finishes before he comprehends what is going on.

Also you make a mistake interesting you can be hours from another run vs 60 seconds from a new lap.

I have been lucky to know a few teams and drivers. I have seen this up front and close. This is pretty hairy stuff. Many of these drivers are not big time and spend a lot just to run a few times a year. It is expensive and the winnings won’t cover the fuel bill.

What a great piece

dennis- I’ve used that expression countless countless times… to describe a variety of things… one in particular and by far the most… usually followed by “of ” … a painting or would then rank second. I appreciate your brevity but sometimes clarifying the comment is helpful. I mean Ron is kinda cute but…

Amazing vehicles. I love how there is no way to analyze the data live because the race is over.