Media | Articles

Right Seat: Confessions of an on-track driving instructor

She shifts the 911 from third gear to fourth just as the rev limiter kicks in, and we shoot past 100 mph headed down the main straight at Carolina Motorsports Park. I look over at the woman holding the steering wheel and ponder Turn 1 as it rushes toward us. It occurs to me that I met this person fewer than 100 seconds ago, and our lives are in her hands. What if she never brakes? What if we blow all six air bags in a flaming exit from the track? David Byrne’s lyric comes to mind: “How did I get here?”

Such is the life of a track instructor: They pay, you pray.

As the first braking marker approaches, I am relieved to hear her lift off the gas. Before I can compliment her good judgment over our helmet intercoms—WHAM!—we are both thrown against the car’s shoulder belts as she engages full ABS. I pull my retinas back into place and calmly offer a short tutorial on braking markers, suggesting that she need not brake so hard, or so very early. These first lap jitters soon settle down, however. We get five more laps under our belt before the session ends. By the sixth lap she is much smoother in her corner entries, and she follows instructions well enough to have a pretty good line. In twenty minutes she’s doubled her driving skills. By sunset she will be faster than some and happier than most of this track day’s fifteen participants.

More so than any performance upgrade to the car, improving one’s own capabilities is essential to both going faster and driving safer. At these events you may see a 20-year-old driving their mom’s automatic Hyundai Tiburon and learning right alongside the experienced track rat running an Ariel Atom. Everyone leaves faster. Focused practice makes perfect, just like your high school coach told you.

Trust the process

I’ve been instructing drivers since 1985. Back then, I used to help Dick Turner with his driving schools (mostly autocross-style parking lot events), graduating to track events with various groups over the ensuing decades. Lately I’ve been involved with Siegel Racing Driver Education Clinics (SRDEC) across the five main road courses in the Southeast. I always have a blast; instructors don’t generally get paid, but we do get free track time for our own rides. Many other organizations run track days such as NASA or SCCA. It’s a great outlet for lots of folks who get to run their cars and themselves at full song for a day.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Over the years I’ve come to love the experience of seeing a novice driver’s transition from trepidation to terror to tenacity, and finally to total control of their car. That progress is extraordinary. It usually only takes one day for a driver to “get” the whole “car at speed” thing. Most schools use in-helmet intercoms which pick up everything, including each other’s breathing rate. As an instructor, it’s literally like getting inside someone else’s head to hear them grunt, gasp, and gulp as they work their car around a course. For some it can be an athletic event (relaxed smoothness is more typically the goal) and you can literally hear the adrenaline ramp up over the intercom as each sessions starts.

For some students, the lessons begin with having them find the rev limiter. Not everyone initially permits themselves to do this. I get them to bang up against the limiter and hold for a second, dissipating their fear of mechanical meltdown. Next comes exploration of threshold braking, or ABS engagement if so equipped—again, something that not all drivers are accustomed to. After that we work on cornering limits (let those tires make some noise!) and finally balance and transitions into, through, and out of corners.

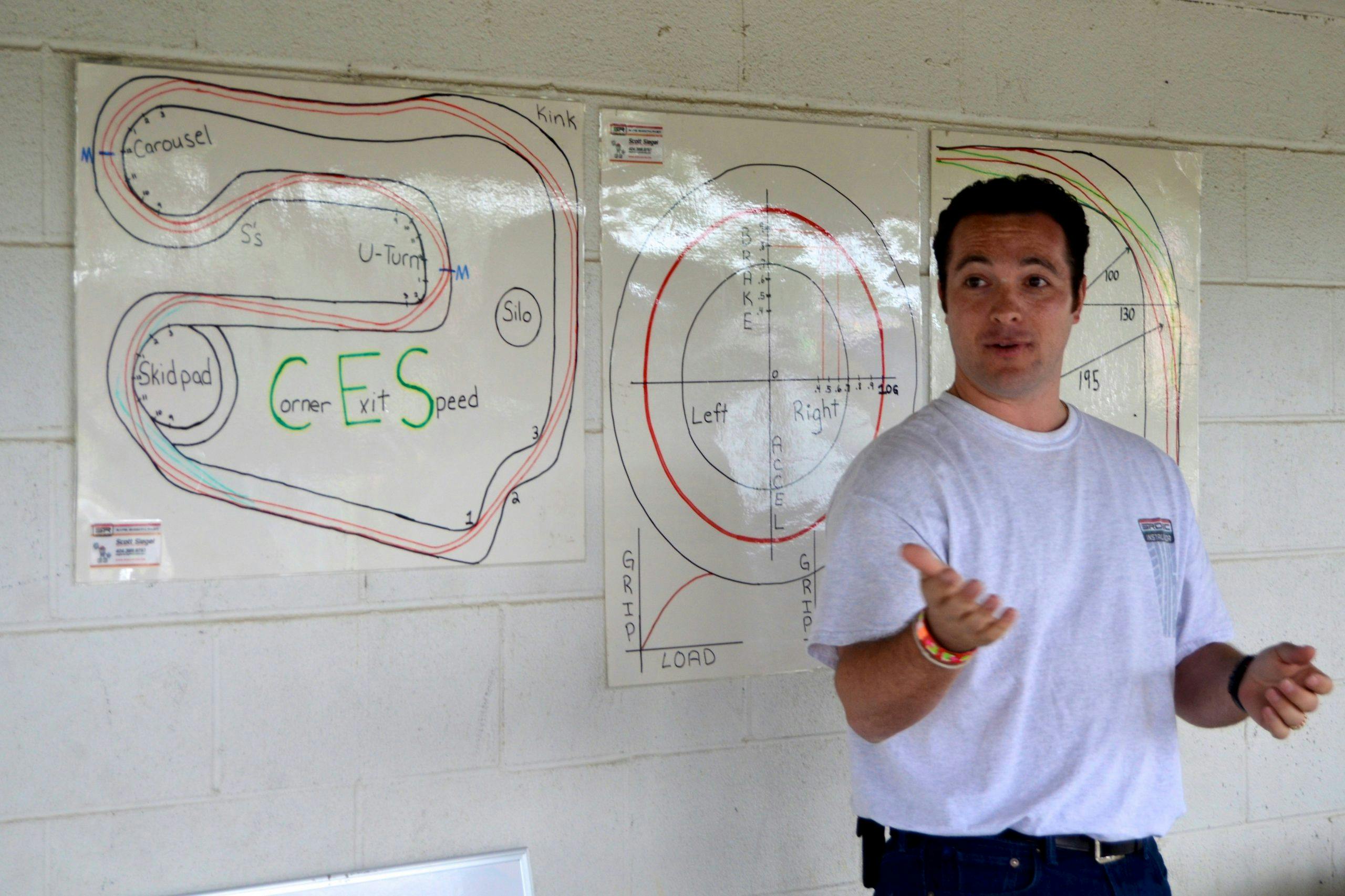

Drawing out a friction circle and talking about using each moment of the track lap as a time for optimization would have been Greek to newbies in the morning, but by the afternoon sessions it makes great sense. Students learn to either always be accelerating fully, braking hard, or cornering strong in each section, and they work on getting their confidence and level of “guts” elevated. Most drivers have a pretty good appreciation for the traction limits of their cars from their street driving experiences, and most are pretty wise about creeping up to find these limits in each corner of a particular track. Lap-by-lap, they learn their car’s edges of performance and get faster and faster each lap—to the great satisfaction of driver and instructor alike.

Fear factor

One driver took me by surprise, however. We were on our first lap together going around Virginia International Raceway and had made it to the main straight without a hiccup, and he had shown a very aggressive “late apex” style as he warmed up on the slow first lap. I thought he might be pretty fast once he opened ‘er up. Turns out he had a different mindset going. We exited Hog Pen with a good line and great speed. As we passed the 110-mph mark along the straight and the braking markers came into view, I was impressed at how he was keeping his foot on the floor. Most drivers lift the throttle and coast a bit, long before they intend to brake (the aforementioned 911 driver being an exception), which wastes precious seconds that could be spent accelerating.

This driver, however, showed enormous confidence in both his driving skills and in his car, because he blew past the first marker with his throttle wide open. “Man”, I thought to myself, “This guy’s g-o-o-d…” as we approached the second brake point marker. It was at this moment that the small voice of reason chimed in and reminded me that we were on street tires and in a BRZ, whose trajectory for Turn 1 would need to be entirely different than the velocity and vector we were on at the moment. I yelled “BRAKE” through the intercom as we passed the last marker, realizing that this guy had no fear of speed or consequences of his actions.

He responded to my bark by slamming on the brakes, catching traction on the last 30 feet of disappearing asphalt. We exited the track at 80 mph and skidded to a halt in the dry grass. I, uh, re-calibrated my technique with this gentleman and advised him that it is very bad form to leave the track. “You get two more of those and then you go home,” I said. We only had one more off-track moment that day, and in the end, we were able to use this guy’s fearlessness to great advantage. Properly managed, his boldness turned into blistering lap times, and at the end of the day I was envious of his lack of fear. A little tuning was all he needed.

Style points

Each instructor has their own teaching style. Some teach with a “stream of consciousness” style of ongoing banter, others won’t say a word until you do something wrong. Know your preferred learning style and ask accordingly. If you are stubborn and pig-headed about your driving skills (as I am), you may need a real drill instructor to get you out of your bad habits. If you are just having your first track experience but are familiar with autocrossing, you might appreciate more play-by-play coaching about the correct line and braking points as you progress around the track. If you’ve never been on “at speed” before, you should ask lots of questions and listen to your instructor. Get your money’s worth and move up the ladder of driving skills as rapidly as you can, one track day at a time.

I recall an event held at Atlanta Motorsports Park. A businessman in a brand-new Porsche 911 Turbo was wrestling the car around the track in his first few laps like a gorilla trying to open a suitcase. I could tell he was having difficulty processing all of the inputs that come to you when you are moving fast on a curvy track. High speed in a straight line on a four-lane highway is one thing; dealing with the consequences of speed on a road course is an entirely different animal. I learned to drive in rickety old English sports cars on bias-ply tires, so my default driving style is to be as smooth as I can. (Jackie Stewart is always my head reciting in his Scottish accent: “You’ve got to be smooth, son,” when I start a track day.)

This Porsche driver was the opposite of smooth—tense and jerky as he made his transitions from corner to straight and back into corners. Going from full throttle to full brakes to full cornering potential in a street car is mildly discomforting. Doing this in a car with the performance capabilities of a Porsche Turbo is like being bounced down a hill inside an oil barrel—you can feel 1G (or more) in any particular axis instantaneously if you drive in a square-wave pattern of inputs and forces.

I kept prompting him to relax and to ease up on the controls. He was literally white-knuckling the car around the track. By the second session he was not responding to my suggestions and had plateaued at a low-novice level. I had to find another way to break through the wall he was putting up. As we flew down the back straight at wide-open throttle, I could see his forearm muscles flexed to full strength. Breaking a number of social protocols, I reached over and gently put my hand on his arm’s rigid muscle, held it there, and spoke to him calmly through the intercom. “Your car is a violin, not a hammer,” I said to him. Slowly I felt the sinews in his forearm relax and his breathing slowed down. This was all he needed to hear. I told him to drive with only his fingertips for a few laps, and soon his ham-fisted driving had turned into a ballet of man and machine.

Ego gets in the way

Your instructor is a better driver than you are. Remember, that’s what you’re paying for.

For instance, if I am on track barreling down a straight and headed for a turn, I might say “brake at the first marker”. An overly confident driver might hold his speed up to the first marker and then test to see if he has the guts to hold on “just a bit longer” (just because), and then he will brake when he thinks it is best. If his car can handle this technique, he will be so pleased with himself he will lose focus for a moment and ceremoniously exit the corner onto the grass because he forgot all about the apex while he was basking in the glow of his gutsy braking maneuver.

My experience has been that women often make for better driving students. I think back to one particular Talladega Gran Prix SRDEC event: There is a great married couple who frequently attend and bring two separate cars. One is the husband’s new BMW M3 and the other, driven by the wife, is the husband’s old M3. I was instructing the wife and we were working on late apexes, getting the tires to “sing loudly” through each corner, and on aggressive throttle control mid-corner. Working in the older, slower M3, we were able to steadily improve the wife’s lap times in each session. On some laps, it was almost like flying a drone: I would say “throttle, throttle, throttle…” to keep her foot planted on the gas going down the straight, working to get her to the correct brake marker, and then I would yelp “brake” about half-a-second before we needed to hit the binders, and she would do it. Right on the mark, right on time, every lap. More importantly, she would remember it on the next lap, and work on optimizing a different corner. Instructing her was like writing lines of code into a driving robot. Eerie, almost. By the end of the day, she had dissected the entire track and worked out the best combination for each section, with faster lap times to show for it.

In the last session of the day as the shadows grew long, it came to be that her husband had passed (aka had been waved-by, as is done on track days) all the cars behind his wife’s M3 and we found him on our tail. His wife, now inspired, hunkered down and ran her fastest two laps of the day. In a few of the corners, she was obviously out-pacing her husband, and the most beautiful gleam began to fill her eyes. When we pitted after the cool-down lap, we all witnessed a proud husband run up and embrace his wife, congratulating her on her newfound speed and performance. This still stands as one of my favorite moments as an instructor: a willing student in a capable car making strong improvements with the full support of her teammate. All egos were checked at the door, and everyone left the track faster for it.

Everyone can benefit from some outside coaching. Even we instructors take laps together and teach each other how to optimize our techniques. Driving is an acquired art, after all. No two people approach it the same way. And isn’t this why we fix, modify, and dote over our performance cars—to make them perform better? Take yours out and exercise it on a track, but prioritize improving your own skills. It would be a shame to spend thousands upgrading your car’s engine and suspension without addressing the nut that holds the steering wheel.

***

Norman Garrett was the Concept Engineer for the original Miata back in his days at Mazda’s Southern California Design Studio. He currently teaches automotive engineering classes at UNC-C’s Motorsports Engineering Department in Charlotte, North Carolina and curates his small collection of dysfunctional automobiles and motorcycles.