Media | Articles

Remembering Craig Breedlove, hot-rodder turned fastest man on earth

We originally published this story upon the death of Craig Breedlove on April 4, 2023. We’re re-sharing it on the anniversary of Breedlove’s 600.601-mph record set at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah in 1965, when he shattered a land-speed record that had stood for nearly 20 years: 394.2 mph, set by John Cobb in his Railton Special in 1947, also at Bonneville. — Ed.

On October 15, 1964, seconds after pushing the land-speed record past 500 miles per hour on the Bonneville Salt Flats, Craig Breedlove punched the button to release the parachutes attached to his jet-powered Spirit of America. They all failed. He careened off course, sliced through a pair of telephone poles, catapulted over a berm, and nosed-dived into a brine lake.

Fortunately, he’d had the presence of mind to unlatch the canopy while he was in the air. As water flooded into the cockpit, he popped his harness and swam to safety. Soaked but unhurt, he was lounging on a piece of debris when the emergency crew arrived. “And now for my next act,” he told them, “I’m going to set myself on fire.”

Breedlove, who died Tuesday at the age of 86, was the first man to exceed 400, 500, and 600 miles per hour on land. Immortalized by the Beach Boys as “a daring young man [who] played a dangerous game,” Breedlove was the winner of a thrilling, high-profile, three-way land-speed battle with the Arfons brothers in the fall of 1965. After a frantic six-week stretch of steely-eyed one-upmanship, Breedlove ended up holding the record at 600.601 mph.

Born in 1937, Breedlove was a prototypical SoCal hot-rodder who pushed a supercharged ’34 Ford coupe to 154 mph on the dry lake at El Mirage before graduating to an Oldsmobile-powered belly tank that went 236 mph at Bonneville. After a stint at Douglas Aircraft, he worked as a firefighter in Costa Mesa when he was bitten by the jet-engine bug.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Although jet-powered dragsters had been on the exhibition circuit for several years, Los Angeles physician Nathan Ostich was the first man to take a jet car to Bonneville; his Flying Caduceus topped out at 331 mph in 1962. Later that same year, jet dragster driver Glen Leasher was killed when his land-speed car, Infinity, snap-rolled at close to 400 mph.

Meanwhile, Breedlove spent $500 to buy a General Electric J47 turbojet salvaged from a Korean War-era F-86 Sabre. Working out of a garage near LAX Airport, he fashioned a low-slung, three-wheeled streamliner that he dubbed Spirit of America. The name was pure marketing gold–a sign of his promotional genius. Handsome and personable, Breedlove lined up sponsorship from Shell and Goodyear. In 1963, while wearing sneakers and a crash helmet festooned with painted stars, he claimed Fastest Man on Earth honors with a speed of 407.447 mph.

Breedlove returned the next year to set two more records. In 1965, he faced fierce competition from Art and Walt Arfons–two middle-aged Midwestern brothers who worked out of adjacent junk-strewn lots in Akron, Ohio, separated by fences and decades of estrangement. To outrun them, Breedlove built a four-wheel car, Spirit of America–Sonic 1, around a more powerful GE J79 taken from an F-104 Starfighter. It was in this car that Breedlove claimed his last two land-speed marks.

As a cherry on top of this sundae, he also co-drove to endurance records on a large oval marked out on the salt in a Cobra Daytona Coupe in 1965 and then an American Motors AMX on a Goodyear test track in Texas in 1968. Breedlove was 31 years old, and he would never scale such rarified heights again.

Breedlove’s land-speed record was shattered in 1970 by Gary Gabelich and the rocket-powered Blue Flame. Thirteen years later, Briton Richard Noble raised the record to 633.47 mph in Thrust2. But one great prize remained: breaking the sound barrier.

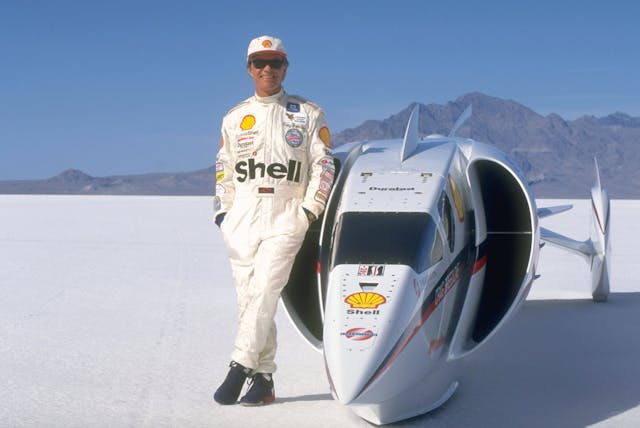

After spending three decades making money in real estate, Breedlove designed a third Spirit of America around another J79, this one out of an F-4 Phantom. With a small team and sponsorship from Shell, he put the car together in a shop he’d fashioned out of an old Ford tractor dealership in the small Northern California town of Rio Vista. “We built everything from scratch, just the way I did the first time in my dad’s garage in El Segundo,” he said.

By 1996, Bonneville was no longer big or smooth enough for land-speed attempts. Instead, Breedlove headed to the concrete-hard playa of Black Rock Desert, now better known as the home of the annual Burning Man bacchanal. Just before starting a run, he misheard a radio communication about the speed of the crosswind blowing across the course–not 1.5 mph but a potentially catastrophic 15 mph.

Unaware of the danger and eager to get the run in before the weather deteriorated, Breedlove took off and lit the afterburner. While he was thundering along at 675 mph, a gust buffeted his car and sent it up on two wheels. Bicycling wildly, he executed the world’s fastest U-turn and screamed through the spectator area. Although he miraculously avoided hitting anything–or anyone–the car was damaged too badly to continue.

Breedlove returned the Black Rock Desert the next year to go mano-a-mano against a well-funded British team lead by Richard Noble, who’d hired RAF pilot Andy Green to drive a twin-engine behemoth called ThrustSSC. Breedlove was hamstrung by engine trouble and a lack of money, and he could only watch the shock wave produced when Green broke the sound barrier.

Breedlove spent much of the next decade plotting another assault on the record, but he was never able to put the necessary financing together. Finally, in 2006, he sold his car to adventurer Steve Fossett, who underwrote a substantial redesign. The project died when Fossett was killed in a plane crash the next year while scouting sites for potential record runs.

Were it not for a garbled radio transmission, Breedlove might well have been the first man to officially go Mach 1 on land. Even so, with five land-speed records to his name, he still occupies prime real estate in the pantheon of land-speed-record deities and deserves to be remembered as one of America’s motorsports heroes.

“The thing I admired most about him is that he was so dedicated to breaking the record. It was his entire life,” says BRE founder Peter Brock, who spent six weeks on the playa with Breedlove in 1997. “He built three land-speed record cars in his garage and spent every dime he had on them. We’ll never in our lifetime see a guy like him again.”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Via Imola

Craig was a true hot rodder. He was not about billet bling or such as as he was about quality building and speed. How many people could build cars like this in a simple shop today.

I was always a fan of Craigs even as a child. I even once was put in the driver seat of Sonic one and played with all the controls. I grew up near the Arfons too.

To me this is a lost era where so many buy fiberglass Cobra kits and assemble them thinking they are hot rod builders.

Today the speeds are so high and the technology to go faster is not as simple as it once was. I am still waiting for the Bloodhound to make a run. I know Richard Noble is not a part of the program any longer but I would love to see his car top the 1,000 MPH mark.

I know Craig would have liked to seen that too. I know his car would have done it had he had more money and a little more work.

Names like Craigs , Gurney and Thompson all were the true hot rod spirit and did things people that were just kid playing with cars should never have accomplished.

The years after the great war and the aero industry turned the LA area into a hot bed of skilled workers and these were just some of them. Even Shelby benefited from this.

Let’s not forget the car Challenger 1, a four Pontiac 389 engined car that set land speed records for piston driven engines. It went over 400 mph. I remember it well. In 1963 I built a model from AMT of it.

R.I.P. Craig – you are an inspiration to several generations of folks who, like you, feel “the need for speed”. 🙏

Godspeed Mr. Breedlove. Godspeed!

I remember when I was a kid and was fascinated reading the article about the Sprit of America.

RIP and don’t get caught speeding in heaven Mr. Breedlove.

I was a teen in the LSR era and was captivated by the competition and Mr. Breedlove in particular. I submitted my renderings of the first two “Spirit of America” vehicles for extra credit in my Architectural Drafting class; much more fun than the straight lines of a house. Piloting real cars to records is a testament to his determination to dominate that arena. God Bless You!

So was I: he was one of my teenage idols; with the good looks of a Clint Eastwood. They sure do’nt make them like that anymore…God Speed Mr. Breedlove and thank you for the excitement you brought us.

Craig Breedlove was also one of my heroes as well. I think his quote after the salt pond incident is my lifetime favorite quote. “For my next act I will set myself on fire!” He was an amazing man.

He couldn’t be caught – he’d be setting a record! We’ve lost another great one!

An amazing story of an amazing brave man. Such a different time and such optimism! We need that to make a comeback.

Movie please !

Craig Breedlove was one of the greats in the automotive world but I have to correct one of the statements in the article. He was not the first to exceed 400 MPH as stated. The first was John Cobb who had a one way run of 403.135 MPH in 1947. Mickey Thompson ran 406.6 MPH in 1960. Neither set an official record over 400 (the average of two runs is required for a record) but they did exceed that speed on one run.

Great catch. I should have said “officially.” Along the same lines, I’m convinced that data recorded by an on-board accelerometer and analyzed by an Air Force officer confirmed that Stan Barrett broke the sound barrier in 1979 in the Budweiser Rocket. But he (arguably) exceeded Mach 1 for only an instant, so it wasn’t an “official” record. And whether or not Barrett got to Mach 1 first takes nothing away from the enormity of Andy Green’s accomplishment.

Stan Barrett absolutely did not break the sound barrier and the suggestions that he did ranged from wishful thinking to outright fraud. I don’t remember the details, but Craig told me all about it years ago.

I remember seeing photographs of the Budweiser Rocket supposedly at the moment the car exceded Mach 1. It showed the nose of the car lifting and dust being stirred up ahead of the front wheel as a result of the sonic boom from the nose of the car. There was a comparison photo taken at lower speed showing the front of the car lower and the dust being stirred up behind the wheel. I assume they had cameras lining the course. I remember the speed being determined by Air Force radar.

If it can’t be proven, it’s not a part of history. Even Wikipedia says it probably didn’t happen.

He may have exceeded the speed of sound but it will never be official as no back up run was ever done.

This is an argument about little.

Green did it in the Thrust so that is all that matters.

Even Green was a full lock as the car was leaving the ground. It was by the grace of God he did not crash. That came right from Richard Nobel.

An object moving through the air near Mach 1 will have localized areas exceeding Mach 1. The OBJECT isn’t necessarily exceeding Mach 1

My very first memory of anything automotive, other than the family ’60 Ford wagon, is Craig Breedlove and the Spirit of America. Godspeed, old friend.

Very sad today. I called Craig my boss and my friend. I was his marketing director and we lived together at his shop 20 years ago when we were seeking sponsorship from the National Guard to run his car on the Black Rock Desert to break the record. The war in Iraq ended our plans. The Spirit of America Sonic Arrow was eventually sold to Steve Fossett, who died in a private plane crash when he was actually scouting out some new place to run the car. The car now sits forlornly in a Denver museum…not in the Smithsonian in Washington where we wanted it to be. I was hoping he could resurrect an effort as he had a lot of plans on the drawing board. He did get his biography written a few years ago. Order “Ultimate Speed” by Samuel Hawley on Amazon for the incredible story of this fearless sportsman, my childhood hero….and my friend Craig Breedlove.

What got me was how much these guys were competitors but in the end they became cheaper leaders for the other guy.

When I met Richard Nobel the Arfons family was there where he spoke. Craig also helped Richard where he could with what he had learned.

Even Walt and Art Arfons were major rivals but grew closer as time went on. They built jets in the same shop here but seldom spoke. One Goodyear backed one Firestone.

Walt and Art are both gone now but the shop is still there and Arts son is still rebuilding jest for cars and track dryers.

As a twelve year old in 1968, the coolest land speed record should have been the fastest thing on wheels, but, to me, at that time and evidenced in my 1968 issue of Guiness Book of World Records, was the Longest Skid Marks by Mr. Breedlove in 1964 when his Spirit of America went out of control at Bonneville and skidded nearly six miles.

How about Ken Warby, M. B. E., fastest man on water? Recently passed in Cincinatti, Ohio area, this Austalian demonstrated all the characteristics (homebuilt, jet powered, building another version to raise the bar!) mentioned in the story, just a changed location and medium of attention! Godspeed, both gentlemen!

There was a story one time of Breedlove flying over the Salt Flats in a Boeing 727.

The Captain announced he had to apologize to Mr. Breedlove because the 727’s ground speed

was only 550 mph and Craig had travelled over 600 mph on the ground below.

R.I.P. Craig Breedlove – thanx for the memories.

BJ

The Beach Boys wrote a song “The Spirit of America” .

How many people can say they had a song written about them?

Starting when I was a kid could never get enough of reading about land speed record attempts…guess I never outgrew it. RIP Mr. Breedlove