Media | Articles

Our tame fighter pilot goes commando … Jeepster Commando, that is

My first formation takeoff was a bit of a fail. I understood academically what was supposed to happen, and I had chair flown it many times sitting at my dining room table (chair flying involves visualizing and thinking through a flight while on the ground at zero knots and 1g). That said, academic understanding plus chair flying wasn’t a recipe for success in this case.

Once both aircraft are positioned on the runway, there’s some non-verbal communication between pilots using cranium nods and hand signals to convey in position, engine(s) run up, and ready for takeoff. The signal to release brakes together is a cranium nod from flight lead, with brake release occurring as chin hits chest. All went well until at the directed moment I forgot to release my brakes. Realizing my mistake, I released them a moment later as my instructor pilot’s voice came over the intercom and colorfully demanded I get off the brakes and into position. There are limitations to how much one can reduce power during a formation takeoff before it becomes unsafe, so physics dictated I stayed well aft and out of position until we were airborne.

***

“Is it supposed to sound like that?”

My wife and I were sitting in the stands at the drag race track not far from our home for open racing (“run what you brung”). We had never been to any kind of race before and she was confused by the coughing and sputtering emanating from a 2008-era Honda Civic as it worked its way down the 1000-foot track (a distance halfway between one-eighth and one-quarter mile). I told her the owner had likely paid lots of money to make it sound like that, although I suspected the driver had hoped for a better return on their investment; the mods were great at noisemaking but not so hot on quickly motoring the car down the track. I could relate, having flown several aircraft seemingly more proficient at turning dead dinosaurs into noise than into thrust.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

While in the stands, I spent some time watching the starting tree so I knew what to expect when it was my turn. Thanks to the internet, I had an academic understanding of the process: two white lights to indicate in position and staged, then the three yellows, and finally the green lights. I explained the tree to my wife, since I was hoping she’d get a heroic shot of me launching forward, front tires nearly off the ground, car body twisting from the excess torque, and leaving my competitor in the dust, much as my flight lead had done to me all those years ago. Per the vernacular, I planned to chop down the tree, go A to B, and drive right out of the other driver’s life. Easy peasy, lemon squeezy (note: likely not part of drag racing vernacular).

One problem: I was driving my grandfather’s 1969 Jeepster Commando, a vehicle I personally rebuilt several years back. Its 225-cubic-inch V-6 provides 160 horsepower and 235 lb-ft of torque. Tough to drive that out of anyone’s life. Plus, it’s shaped like a brick. Although the F-4 “Phantom II” conclusively demonstrated that any shape will fly with big-enough engines, clearly some shapes are more aerodynamic than others. Aware of my vehicle’s limitations, I just had to find the right driver to challenge to a race. Unbeknownst to me, you could just get in line and race whomever you ended up next to; I thought you had to get in line with your desired competitor (also a viable option, though not the only one, as I had supposed).

After passing the tech inspection, I parked and wandered around looking for a vehicle that appeared as out of place as mine in order to challenge its driver. I spied a 1998 Honda CR-V and started walking towards it when I ran into my wife (she’d bailed at the tech inspection) and some friends. After a moment of catching up, I turned back to the CR-V but it was already in line to run. With nearly 200 cars registered to race and most of them just getting in line, I decided I’d find an opponent later, and we headed to the stands.

Training like you fight isn’t just important for fighter pilots or military personnel. Ideally, your training is more difficult than the fight, thereby (hopefully) ensuring your success no matter your field of battle. War isn’t a time to just eke out a victory; immediate and total dominance, particularly in the air, is critical to success. Achieving that goal demands extensive training against challenging threats. With this idea in mind, en route to the track I decided I needed practice launching the Jeepster much like I would at the starting line.

“Launching” is a bit of a misnomer in this case. There’s nothing fast about the Jeepster, as alluded to above. That’s not a knock, simply a fact. When I restored it, I took it completely apart and repaired it as I put it back together. In that process, I upgraded to disc brakes, power steering, and put in an HEI distributor, but aside from that, it’s pretty much as it rolled out of the factory in 1969 (not entirely accurate, but close enough for our purposes here). She’ll drive nicely at highway speeds, but with her three-speed transmission she’s most comfortable in the 50-mph range. She doesn’t stop or accelerate quickly, so I have to be a more patient, defensive driver as we cruise around town. Suffice it to say, I’ve never launched her out of a stop light or stop sign. In my train-like-you-fight launching sessions (on an empty road, naturally), I didn’t notice much difference from a normal start until the last of the four “launches,” when the shift from first to second felt a little rough.

She’d done something like this before. The clutch had slipped and wouldn’t shift out of first. The only way to get it into reverse had been to shut off the engine and then shift, repeating that process to get it back into first, but shifting to second had been totally out of the question. The clutch is a Rube Goldberg machine of unnecessary complication, with adjustment possible in at least four different places. My undergrad degree is in electrical engineering, so I’m not dumb, but adjusting that clutch befuddles me. After a long time lying on my back under the Jeepster, staring at that convoluted clutch, I opted to limp it in first gear to my neighborhood mechanic who had it adjusted in just a couple minutes.

Heading to the track, feeling the change in the clutch, I was afraid it would stick as it had before and I wouldn’t be able to race at all. My fears were confirmed when I had to use reverse in the parking lot by registration and she loudly, grindingly protested. Knowing it was only a 1000-foot track, and estimating I’d be slower than 60 mph at the finish, I knew I only needed one shift from first to second to be able to race. As to a clutch adjustment in the paddock, its perplexing nature made such an adjustment impossible—at least for me. I was going down that track, marginally functional clutch or not.

Speaking of shifting, the Jeepster does not shift quickly even in the best of times. Clutch pedal throw measures a whopping 6 inches. As mentioned above, she has a three-speed transmission, but reverse is in the top left corner, meaning a shift from first to second requires moving from bottom left to upper right. Once the clutch is in, it’s 3.5 inches of travel from first to neutral, an astounding 4 inches across neutral before another 3.5 inches up into second. Once in second gear, it’s another 6 inches to let the clutch pedal back out. Even if I’m trying to do that quickly, it takes at least 1.5 seconds per shift, another reason I only wanted to shift once while roaring down the track.

Side note: Prior to her rebuild, the Jeepster had straight exhaust pipes (no mufflers). That was evident by how loud she was, even at idle. Newly rebuilt, I took her to the exhaust shop and told the guy I wanted straight pipes. He looked at me incredulously and I told him that’s what my grandfather had on it, so that’s what I wanted. I’m sure he said something about how loud it would be, but I insisted and he demurred. It was way louder than I had anticipated. It was impossible for anyone to carry on a conversation within a two-block radius of the Jeepster, so I later had a muffler put on each exhaust. She’s still loud, but not like she had been. If nothing else, I figured she’d fit it at the track by virtue of the noise she’d make.

While chatting with friends in the stands, I watched an old-school VW Beetle run just over 20 seconds and hoped I’d be able to run sub-20. The CR-V’s turn to race arrived and it matched up against a VW GTI. Curious as to how it’d do, I watched as the CR-V got out ahead of the GTI, only to be caught on the big end. It ran a surprising 13.4 to the GTI’s 13.1. I knew the only way the Jeepster would go sub-13 in the quarter mile is if it were pushed off a quarter-mile-high cliff, and, due to its brick shape, maybe not even then. I was glad I hadn’t challenged him. It would have been embarrassing to lose to a CR-V.

Enough spectating; the moment had arrived. Not wanting to risk losing to a Beetle or a CR-V, I opted to go big and I challenged my buddy to a race. His car? A beautiful 1969 GTO with a 400 stroker (~450 hp). We talked lanes (he let newb me have the right so I could more easily see the tree) and got in line. He had already raced twice that evening and was concerned about how hot his engine was, but I told him he could clearly take it easy against me. I didn’t realize his real fear was how hot the GTO would get while we sat in line as it took us over 30 minutes to inch our way to the start. We’d move 30 feet before sitting for a couple minutes and he’d shut down as we sat. I didn’t have that option, because the Jeepster has a quirk where she doesn’t always immediately restart when she’s warm. Fear of shutting her down and not having her restart, coupled with my fear of the clutch giving out, meant I sat idling that entire time holding the clutch pedal. My left foot was asleep and totally numb when it was finally our turn.

While creeping forward, our lane had the GTO in front of me, a Shelby Cobra kit build behind me, and a McLaren of some variety behind the Shelby. I fought the urge to feel out of place in my yellow brick. It was “run what you brung” and I was not ashamed of what I’d, ahem, brung.

There wasn’t a burnout pad per se, but there was an area you could do a short burnout to warm up the tires. I’ve never even chirped the Jeepster’s tires, so I knew lack of traction wouldn’t be an issue—I just cruising through the burnout area towards the start. Naturally, my left elbow was hanging out my window as, other than my tingling left toes, I was nice and relaxed. After all, I had studied and knew what I was doing.

We made the 180-degree left turn from the burnout area to the starting line and I watched the cars in front of us stage and race off into the night. I expected someone to wave us forward and direct us when to stop, but they just motioned us up and left us to our own devices. My momentary confusion meant my buddy was staged before I even got to the line.

Due to the clutch issues I decided against revving the engine and trying to launch; a slightly-more-aggressive-than-normal start seemed like the best course of action.

Staged, GTO engine roaring, my left elbow still hanging out my window, the yellow lights started illuminating. After the first yellow lit I realized I should have two hands on the wheel. My left arm was still moving when the second yellow lit, but I was ready for two-handed driving by the third and final yellow. It seemed like the GTO leapt forward the moment the lights flashed green and I could have sworn his then flashed red, indicating a false start. Noting that, I thought, “No matter what happens, I’ve won the race.” At that point, I realized I hadn’t yet started driving, so off I went. To reiterate, when my flight lead’s chin hit his chest, I just sat there after the green light I sat there long enough to think I saw a red light and have a conversation with myself about it before driving away. Face palm.

The GTO was gone. I was moseying or perhaps sashaying forward, but moving definitely too slow to be sauntering. It felt like I was roaring down the track, though it’s impossible to hear my engine in the video my wife took.

Partway down the track, the moment to shift had arrived. Would it shift out of first? Would it go into second? Would I get stuck in neutral and be towed off after coasting to a stop short of the finish, ignominiously losing to a Beetle? Would I shell my clutch and/or transmission on the track? I’d love to say the speed of the wind in my face made it tough to breathe, but I wasn’t going that fast and I was just holding my breath. She smoothly shifted from first into second and I floored it again towards a glorious, victorious finish. Opting to disrespect my buddy (who had already exited the track), I touched the brakes just prior to the finish line. After all, he left early and I was the victor. I’d rub it in even if he couldn’t see it so I could talk trash about it later.

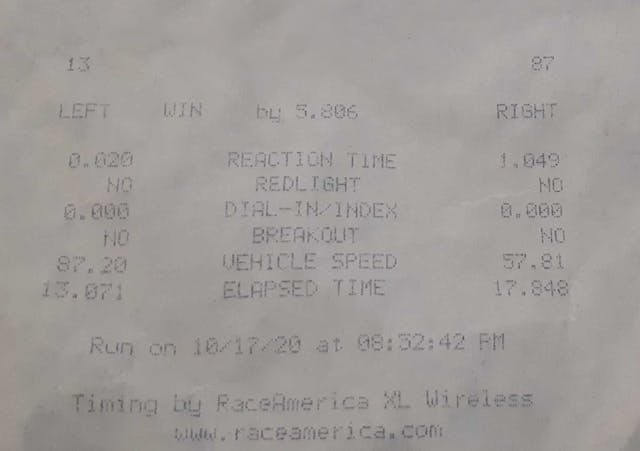

I took off my painfully small helmet as I approached the time-slip area. It was too dark to read, so I took the slip and parked near the GTO. I told him he had gotten a red light and I was the victor. Surprised, he told me to look at the slip. I was stunned to see that not only had he not gotten a red light, but that his reaction time was 0.020 seconds; better to be lucky than good. Remembering the mental conversation with myself at the start, I looked at my reaction time: 1.049 seconds. Ouch. That’s not a micro-nap, that’s slipping into deep REM sleep before gradually awakening, stretching, sitting up, checking your phone, putting on slippers, and finally getting out of bed. No more trash talk from me. Ever. About anything.

Did I at least beat the Beetle? My elapsed time was 17.848 seconds, giving me a total of 18.897 from green light to finish line, so I would have (barely) gapped the Beetle in a race to not be the slowest at the track. I’d call that a Pyrrhic victory. My estimate of 60 mph was pretty good as I crossed at 57.81 mph. My buddy ran an easy 13.071 at 87.20 mph, beating me by 5.806 seconds.

Normally, the Jeepster gets lots of looks wherever I take her, but the folks at the track were far more interested in the Pontiac-powered winner of our 1969 race. Our wives and friends joined us, and we laughed and talked for a while. Looking over to the line of cars to race, I noted it was significantly shorter than it had been previously. Having forgotten the discomfort of the helmet and my sleepy toes, I pointed out the short(er) line to my wife and said I wanted to go again. She laughed and was totally on board. Then, remembering the clutch, I made the tough decision to not give it another go.

Surprisingly, the Jeepster shifted fine on the way home, but she’ll only go in reverse when shut down. I suspect the clutch might need to be replaced soon, and I’m tempted to swap to a hydraulic clutch conversion at the same time. The good news is, I’ve got a couple months until the next “run what you brung” night, so there’s time to get her ready to go, at which point my wife will race her Miata ND against the Jeepster. After all, there’s no possible way her reaction time will be worse than mine! If you see a yellow Jeepster brick at your next track night, don’t bother challenging me if you can’t get it done in 19 seconds or less—’cause I’ll drive right out of your life!