Media | Articles

How the Pinto became NASCAR’s regional weapon of choice

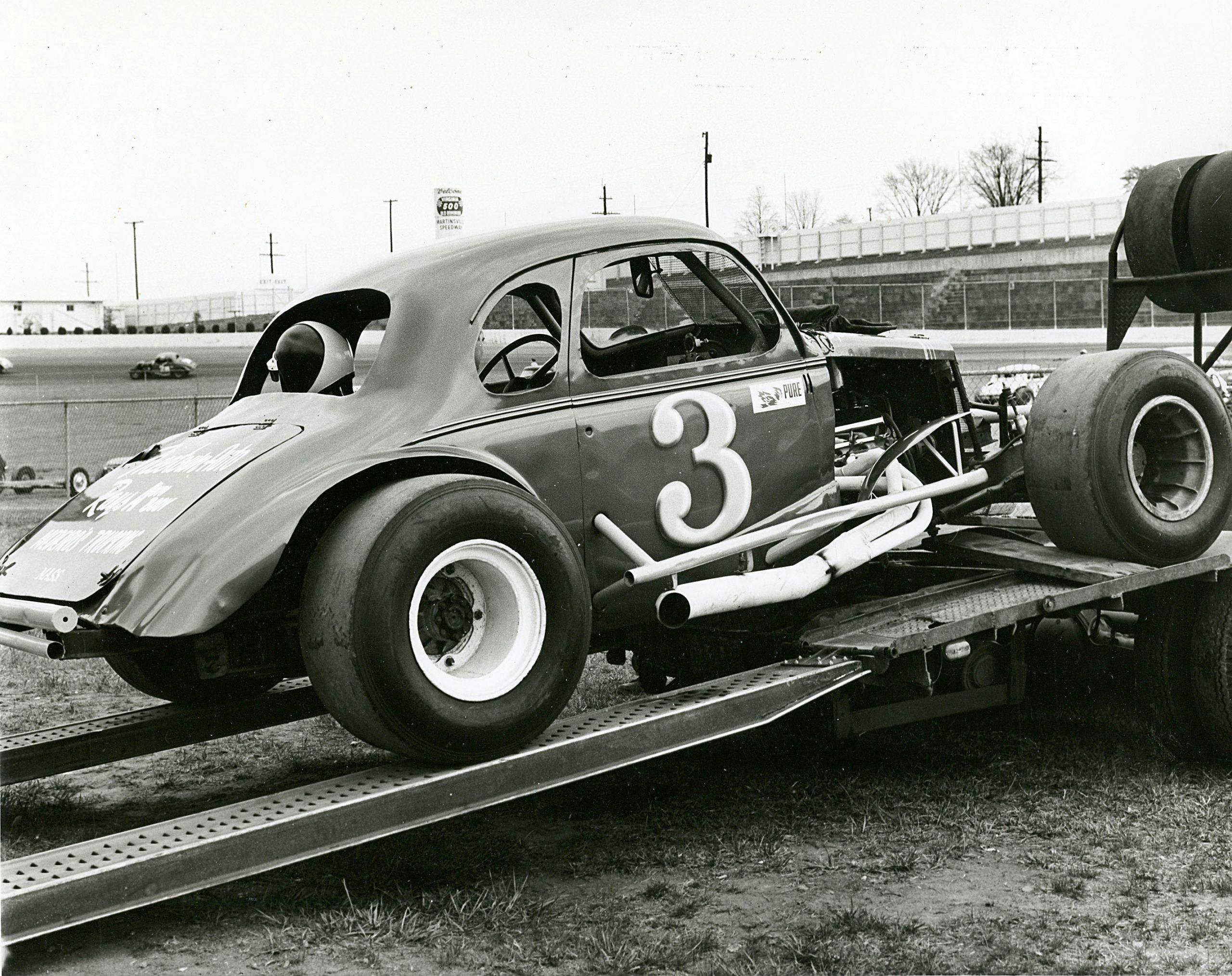

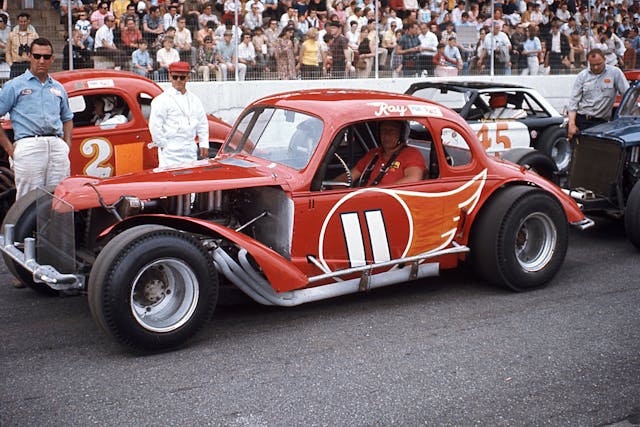

In the late 1960s, NASCAR’s Modified class—one of the first running groups to grace Daytona Beach back in the day—was facing an identity crisis. In the two decades following NASCAR’s debut in 1948, its regional series morphed into flattened pavement-dwelling versions of the cars that ran in the sand. (They never really expanded beyond the Eastern Seaboard.) These low-slung coupe and sedan racers featured steam roller slicks and American V-8s but retained their prewar steel.

That worked just fine until a problem arose. The ancient bodies that teams had utilized since NASCAR’s first dance on the Daytona dirt were becoming scarce in supply.

Two decades of teams operating within the strict confines of NASCAR’s rulebook meant there was no clean slate, and thus no chance for grassroots teams working on a shoestring budget. (Remember, this was a regional series that didn’t receive much in the way of factory money, unlike NASCAR’s later stock cars.) Many of the cars ran on Tri-Five Chevrolet frame rails, Lincoln suspension, and Chrysler torsion bars. Making wholesale changes under the skin of these complex beasts would have been a tall order errand for any outfit.

Instead, teams resorted to a these less-than-ideal solutions:

- Pay top-dollar for salvage yard relics, knowing if they paid any less, classic car restorers—who now found even the most basic prewar domestics to be collectible—would gladly outbid them.

- Rescue a highly corroded example through generous use of Bondo, at the cost of the car being top-heavy after repair.

- Utilize a Camaro, Falcon, or Corvair shell. NASCAR had green-lit these newer domestic models as acceptable modified bodies. With any luck, a builder found a decent example but had to spend hours finessing the cars’ ungainly proportions to fit on the approved chassis.

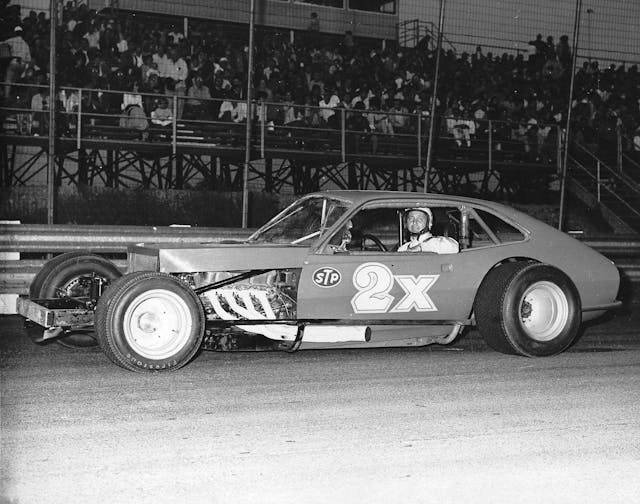

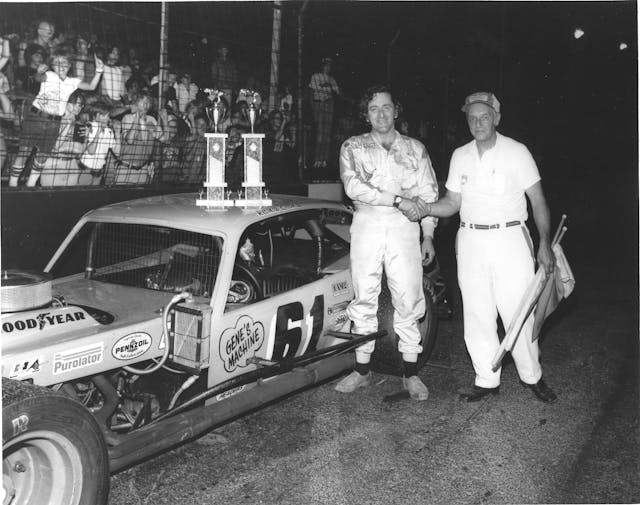

Out on the Berlin Turnpike, in a Connecticut garage bay, a welding torch of defiance sparked into action. Gulf gas station owner Bob Judkins was hard at work fabricating a strategy. Inspired by the numerous Pintos that had rolled up to his pumps during the spring of ’71, Judkins stretched a Ford subcompact of his own over the rails of his modified racer, making use of Dearborn’s sheetmetal from the firewall to the rear clip. “I was coming back to racing after a year off,” Judkins told a regional racing magazine. “I was trying to find something different.” The veteran car owner built a cage to fit his Pinto and hired hot shoe Gene Bergin to pilot it. The Pinto Modified was born.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Since the showroom new Pinto wasn’t approved for NASCAR competition, Judkins and Bergin ran a stretch of open-competition shows throughout the summer. And with Bergin behind the wheel, the Pinto—which looked rather menacing nestled between four giant Goodyear slicks—turned into a mainstay at the front of the pack.

The lack of rules in open competition allowed the duo to run, unfettered, at East Coast bullrings from Maine to Vermont to Connecticut. Meanwhile, Judkins lobbied hard for his creation to be certified by NASCAR big wigs.

The deal was done by late July. In an unprecedented move, NASCAR caved and rewrote its rules mid-season. Likely encouraged that its regional modified series could exist well beyond the inevitable extinction of prewar skins, NASCAR invited any domestic subcompact—including Chevrolet Vegas and AMC Gremlins—to compete in their sanctioned races. Once he had buy-in from NASCAR, smaller sanctioning bodies, even those that raced on dirt, followed suit. Suddenly, Judkins was able to campaign the Pinto practically anywhere.

“When builders change something like that, it takes them a while to figure things out,” says circle track authority Bones Bourcier. “Judkins’ car was fast—and looked good—from the get-go.” Indeed, Judkins and Bergin were victorious after a 200-lapper at Stafford Springs later that fall.

By the next spring, NASCAR’s Modified series, and other local shows, were overrun with Pintos, Vegas, and Gremlins. “You had to wonder where they all came from,” says Bourcier of the new-for-1971 subcompacts. “I know teams got them all out of junkyards, but it was surprising that the public could wreck that many in that short of time.” Those who opted for the new cars weren’t complaining. The flimsy Seventies shells (compared to the overbuilt prewar coupes) were light, allowing builders to bury weight lower in the race car. By 1973, the 1930s shells that once infested circle tracks along the East Coast had all but vanished.

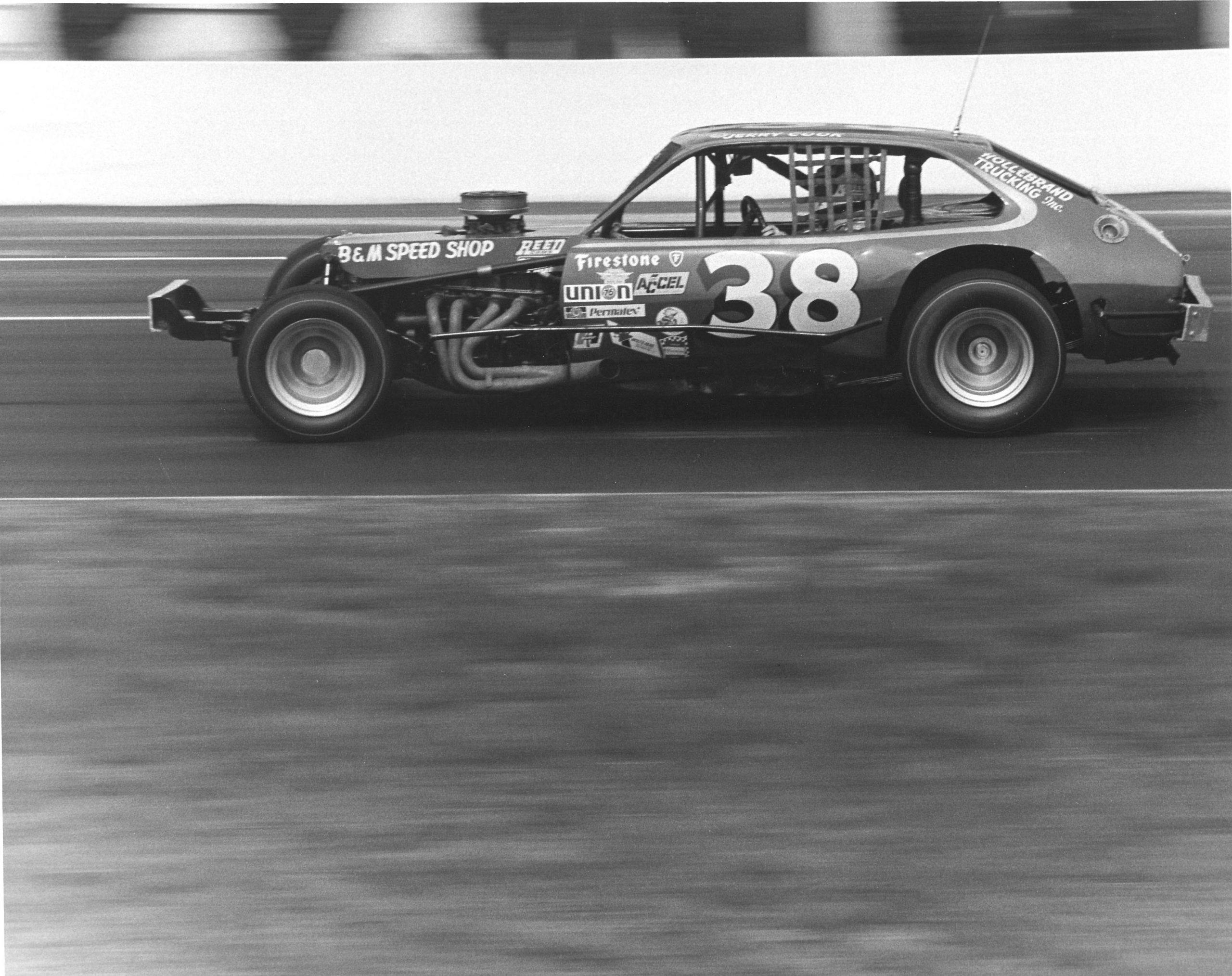

Of the new wave, the Pinto seemed to pack the biggest punch (or, at least that’s what the record books suggest). It probably helped that two NASCAR Hall-of-Famers, Jerry Cook and Richie Evans, prominently campaigned the Pinto for a portion of their most dominant years. Evans, a Rome, New York native, racked up win after win in his Omaha Orange #61 Pinto, further established the subcompact as a sharp short-track tool.

The Pinto’s reign lasted for about a decade, and Cavaliers and Omnis eventually supplanted them as preferred skins. Ford’s subcompact was still in high demand among the circle track ranks, though, as competitors found that the car could be made fast in four-cylinder street stock racing.

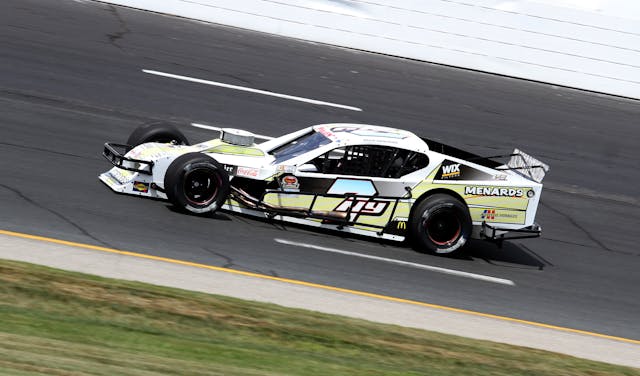

Today, NASCAR’s modern modifieds are largely nondescript fiberglass-and-steel-paneled creatures. Their shape, though, is highly reminiscent of a certain Ford subcompact. Bob Judkins passed away in 2018, but his legacy lives on.

If you enjoyed this story—or have any interest in American circle track racing and its history—check out Bourcier’s books. Thanks for picking up the phone, Bones.