Media | Articles

Homegrown: “Atomic Scalpel” tops 100 mph with gravity alone

Welcome to Homegrown—a new limited series about homebuilt cars and the ingenuity of their visionary creators. Know a car and builder that might fit the bill? Send us an email at tips@hagerty.com with the subject line HOMEGROWN. Read about more Homegrown creations here. —Ed.

Practically every automobile and motorcycle we celebrate at Hagerty employs some form of energy conversion—an internal combustion engine, an electric motor, a turbine, or even human pedaling—to spin the drive wheel(s).

To our amazement, a competitive sport exists in which forward velocity is determined solely by gravitational forces applied on an inclined road surface. What’s known as gravity racing (GR) to a few keen participants is the supreme test of car construction creativity with no help from energy conversion.

It’s Soap Box Derby on steroids.

Doug Anderson, 66, of Fayetteville, Georgia, a retired Delta Airlines technician, built and drove this sleek “Atomic Scalpel” racer in pursuit of gravity-fed glory. Six years ago, at an event called L’Ultime Descente, in Quebec, Canada, the Scalpel became the fastest GR machine in history with a clocked speed of 101.98 mph.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

As it turns out, there’s a long history of racing sans engines. Downhill competition began in 1904 near Frankfurt, Germany. The Soap Box Derby was inaugurated in 1934 by Dayton, Ohio resident Myron Scott—the very man who gave the Chevy Corvette its name. In the mid-1970s, racers competed on a 30-percent grade in Signal Hill, California (near Long Beach), where crashes were common and at least one spectator was injured by a flying skateboard. Fortunately, there were no fatalities. Gravity racing ceased at this location in 1978 over obvious safety concerns. More recently, Red Bull, the energy-drink-hawking extreme sports obsessives, started its own downhill derby series with jumps and obstacles.

“I started GR in 1999 by building what’s called a street luge—essentially a large skateboard,” Anderson explains. “Racing all over the country for three years, I became the Extreme Downhill International organization’s national amateur champion. The team I founded—Bodrodz Xtreme Gravity Racing—continued until 2006, earning several visits to the final competitive rounds.

“In 2016, we advanced to an enclosed gravity car with four wheels, brakes, streamlined bodywork, and a drag chute for slowing the car at the foot of the grade. For inspiration I visited Speed Week on the Bonneville Salt Flats along with a few reunited team members. That convinced us to build the chassis as small as possible to fit the driver with clean bodywork covering the working parts to manage airflow.

“Colleagues Jason Camp, Chris Schafer, Scott Holsenback, and John Nichols were instrumental in building and campaigning what we christened The Atomic Scalpel. Construction consumed a full year and the car was painted just-in-time for its debut at the 2017 L’Ultime Descente event in Canada.

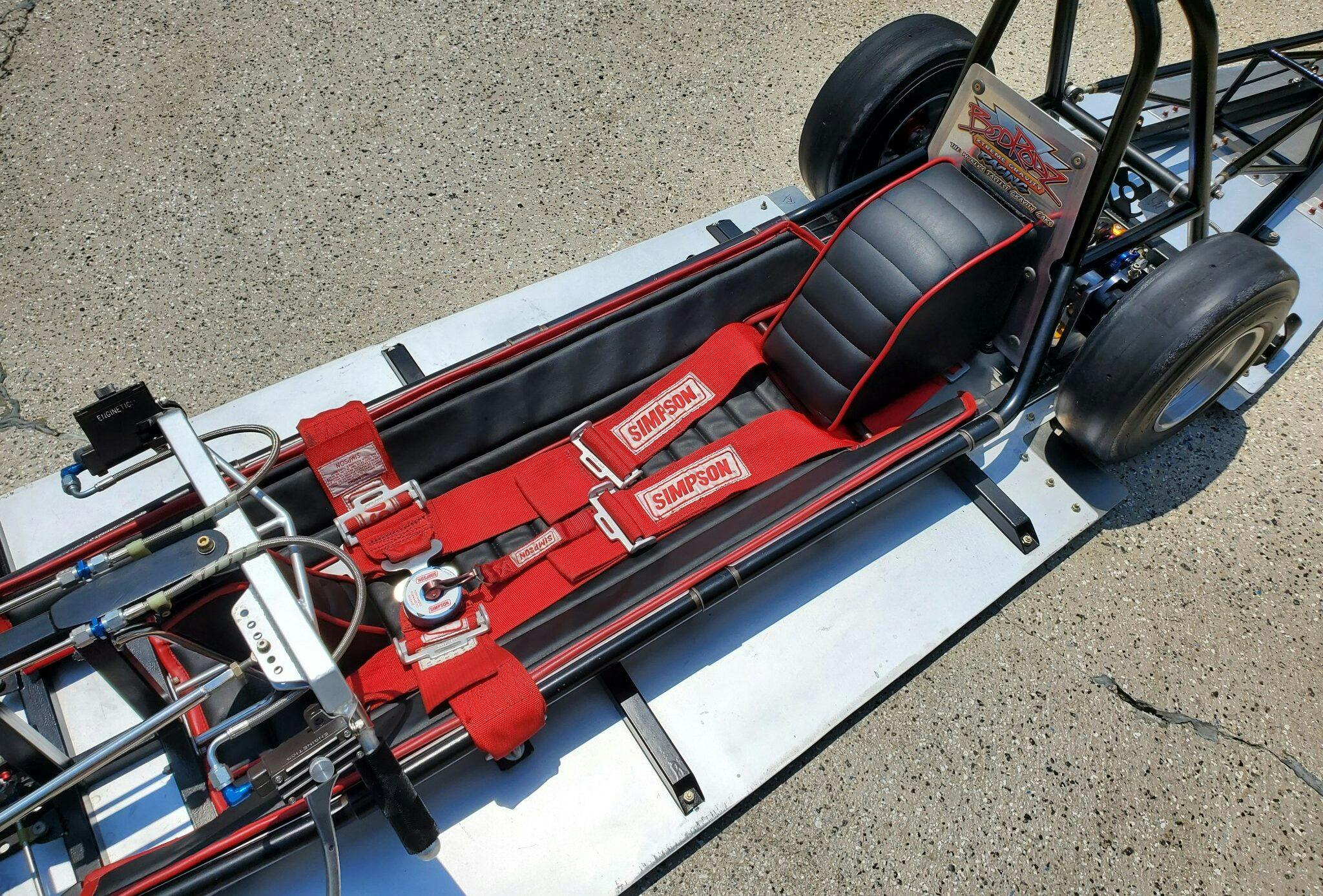

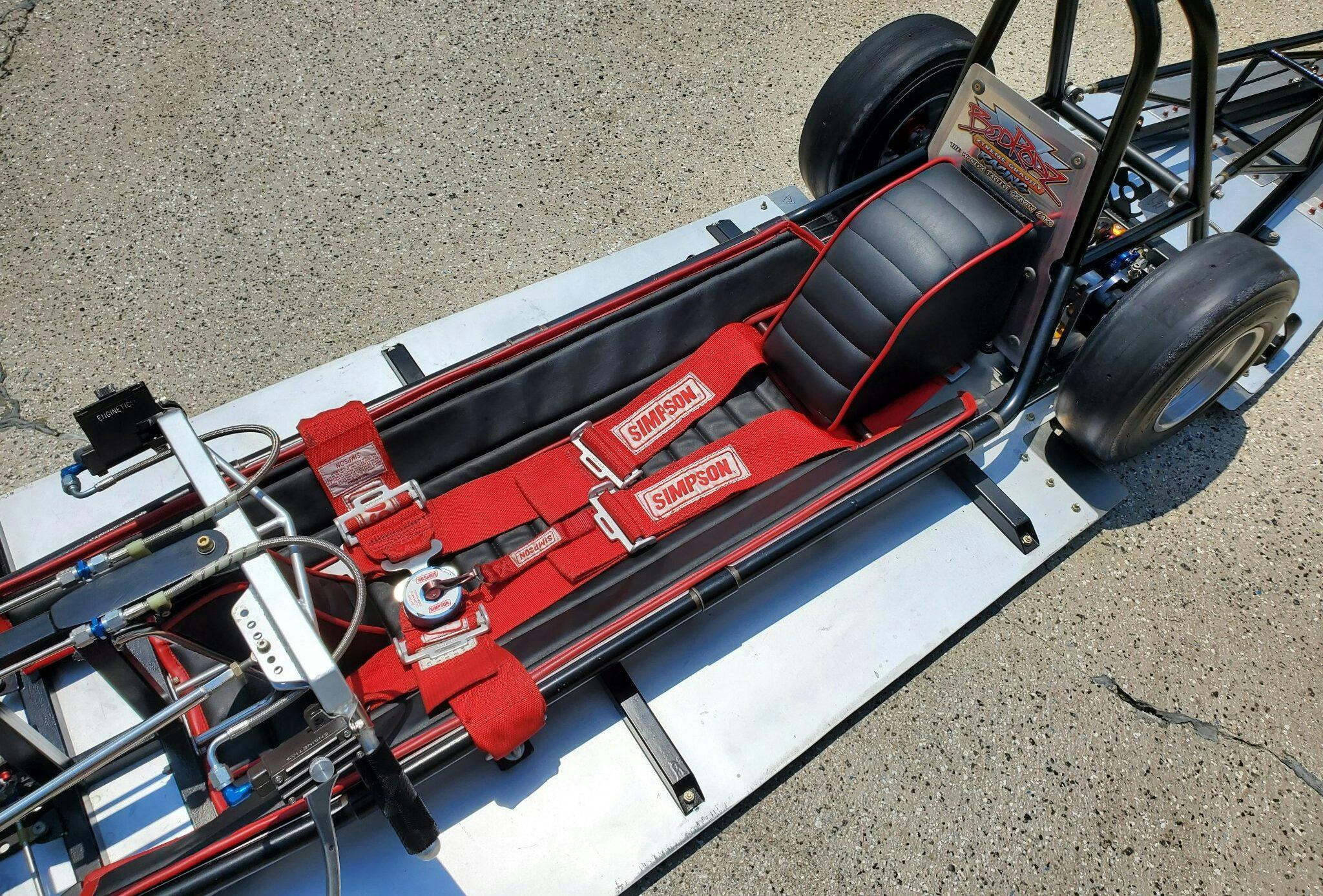

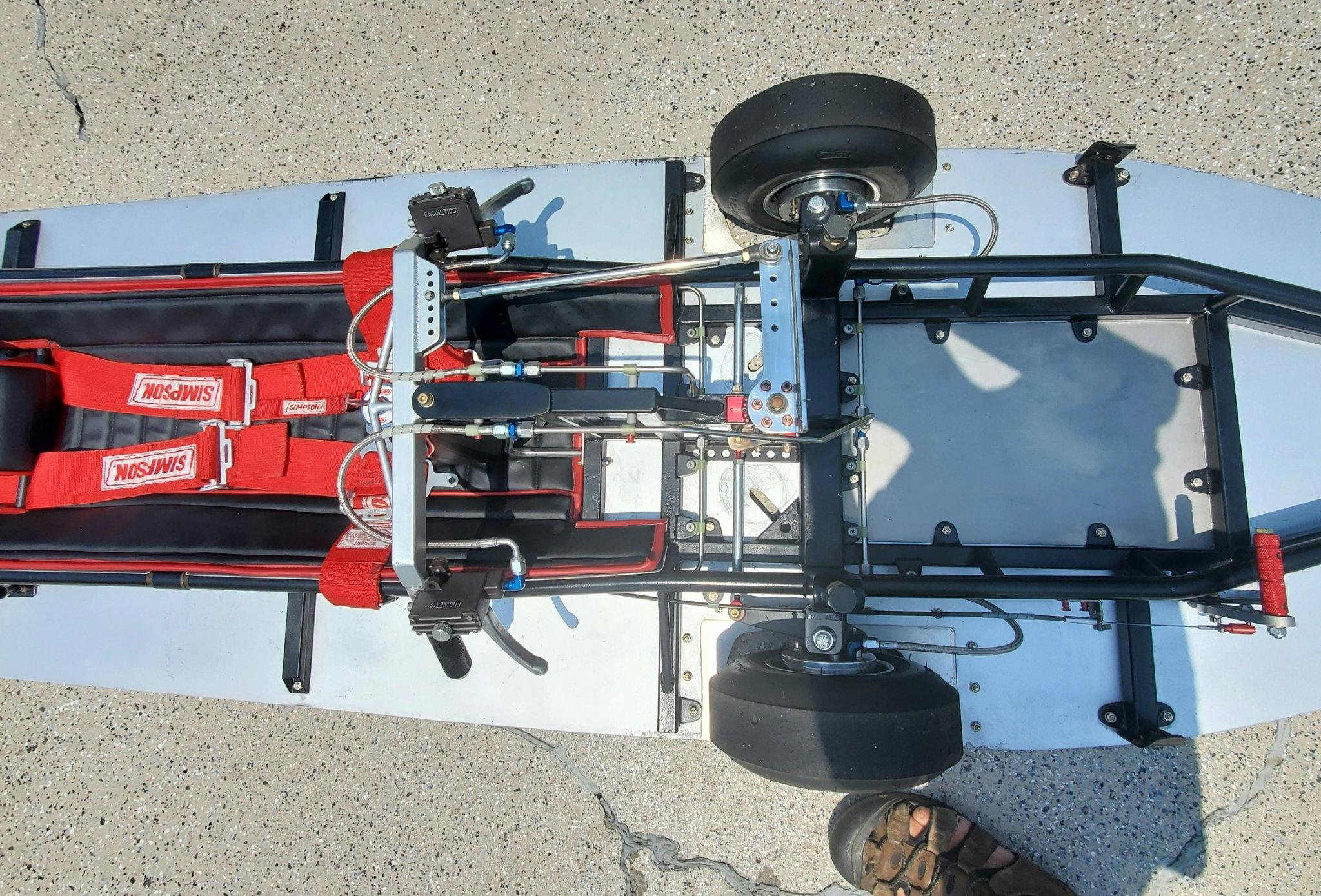

“Our car has a mild steel belly pan to smooth under car air flow and to keep the center of gravity low. The structural space frame consists of chrome-moly steel tubing with titanium used in critical areas. The four tires are high-durometer pneumatic designs inflated to high pressure to minimize rolling resistance. Steering is by handle bars guiding the front wheels and there’s a disc brake at each corner for slowing in conjunction with a custom Deist-brand drag chute. The two-piece body with a hinged section for access to the cockpit is molded foam-cored composite material.”

Pictures do a poor job of conveying the scale. “The body is configured to tightly wrap my 5’8”, 190-pound build,” says Anderson. “Its maximum width is 31 inches over a 58 inch wheelbase. That yields a 520 square inch frontal area; lacking wind tunnel testing, my guess for the drag coefficient is 0.175.”

Scalpel, indeed.

“While the rules allow up to 550 pounds for the driver and car, our combination weighs 470 pounds. Because the course is only 1-kilometer long, adding ballast wouldn’t necessarily yield a higher trap speed.

“With absolutely no opportunity to shake down the Scalpel before competition, I made seven passes hoping for the best. On the 18-percent grade adjacent to Quebec’s St. Lawrence River, I joined the exclusive Century Club with my 101.98 mile-per-hour trap speed, only the seventh effort ever to top 100 mph.

“That record stands in part because there have been no recent gatherings of the World Gravity Speed Association. We’re working diligently to revitalize the sport and there’s a steeply graded road in the southeast U.S. with possibility. In 2022, The Atomic Scalpel was retired and donated to the Speedway Motors Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska, where it remains on display.

“I’m fortunate that my family members support this activity. I’m counting on their backing for one more assault on the world speed record with a new car currently under construction.”

When Anderson returns to the grade, we’ll bring you news of the fresh speeds he’s accomplished.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

I was born and raised in Fayetteville. Good on you, sir.

What the heck is the machinery behind that beautiful blue sixty special?

And what a gorgeous race car that is!!!

Movie projector! Given the automotive theme, perhaps from a Drive-In movie theater.

Looks like old film projection equipment like you would see in theaters.

Way to go Doug it’s been a pleasure working and knowing you for the last 40 years! You always had interesting projects going. Bill G.

Actually, it does involve energy conversion… the car converts potential energy to kinetic energy.

Spot on! Excellent point.

It’s a very neat car. Soap box derby is not as fun as this I bet.

The Speedway museum in Lincoln is outstanding. Definitely worth a visit.

Any idea when Gravity racing will or has resumed?