Media | Articles

Dirt-Track Legend Scott Bloomquist Died as He Lived: Full Throttle

Good reporters keep notes on their stories. Except I didn’t—I keep tapes. Of course, now they are digital files, but once, they were tapes. I learned early on that it was easier to record everything: You can maintain eye contact with your subject, something that’s impossible when you are taking notes. And transcribing the tapes days afterward puts you back in the moment.

Good reporters likely labeled those tapes, but I was too busy. Or lazy. My mistake. I would love to be able to find the tape of an interview I did in 1998 with dirt late model driver and car builder Scott Bloomquist.

Bloomquist has been in the news recently for flying his 1938 Piper Cub into the (closed) doors of a creaky wooden barn on the 140 acres in Mooresburg, Tennessee, he shared with his parents. That was on August 16. His death still resonates in the motorsports community, with a sensational undertone: Was it suicide, or an accident? It’s hard to hold Bloomquist to the accepted norm.

Back in 1998, Bloomquist and I were at Cedar Lake Speedway, a well-kept dirt oval in New Richmond, Wisconsin, east of Minneapolis, at the annual USA Nationals, an annual, big-money event on the Hav-a-Tampa Dirt Late Model tour. Dirt late models look big, but they are just brackets and tubing and air beneath the aluminum body, concealing a 430-cubic-inch, 800-horsepower V-8.

The USA Nationals paid $40,000 to win, a huge purse for 1998. Bloomquist would not win that year, instead finishing 11th, a disappointment for the most dominant racer on the circuit. But he would win in 1999, and 2003, and 2006, and twice more before his luck ran out at Cedar Lake.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

We were in the darkened cab of his 18-wheeler, previously owned by an IndyCar team. The trailer was packed with cars, engines, spares, and about 125 tires—this was before all the big series allowed only one brand of rubber. Bloomquist was a genius at tire choice, chassis design, and aerodynamics, long before that science became popular.

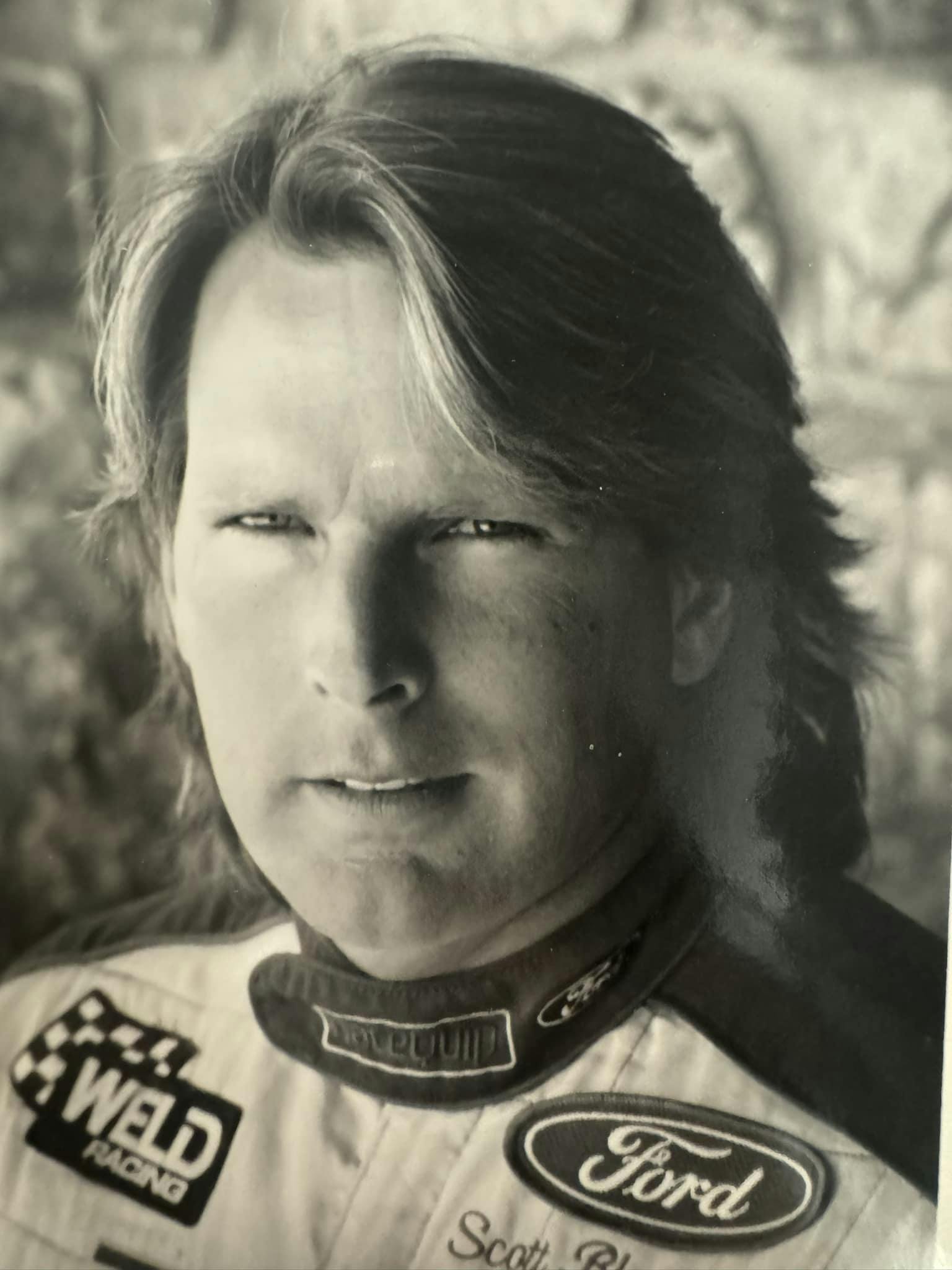

When we spoke that night during the preliminaries, he was the hottest driver on the circuit, and profoundly popular. He was long-haired and outspoken in a sport where clean-cut and uncontroversial were valued by sponsors and promoters, and he was married to the dazzling Miss Motorsports 1991, Midi Miller, whose photos adorned many garage walls.

But Bloomquist’s career was momentarily derailed by a 1993 drug arrest that sent him to jail. As far as drug busts go, it was small potatoes—2.7 grams of cocaine he had obtained for a girlfriend-turned-confidential-informant who, Bloomquist said, set him up at the behest of local authorities eager to make a high-profile bust.

“They’d see us driving a big rig like this one, going out racing every weekend. My hair was longer then. They just automatically assumed I was selling drugs,” Bloomquist said in 1998. In court, the case crumbled, with his conviction declared to be entrapment. But Bloomquist was still convicted on a misdemeanor charge stemming from a straw found at Bloomquist’s house that had been used by somebody to snort cocaine—it still had coke residue in it. In November 1994, he received the maximum penalty possible: $5000 and a year in jail.

The sentence was trimmed to six months on appeal, which he served on work release in 1997, leaving jail at 7 a.m., returning at 9 p.m. It was arguably BS, but it changed Bloomquist, who had never been in trouble. “Thousands of people every year get probation for a first offense and might have to piss in a bottle every week for a while. But they wanted to send me to jail for a year.”

Really, “It wasn’t that bad,” Bloomquist said. “I’d never taken the time to read much before.” That began with Autobiography of a Yogi. And thus began a spiritual quest that Bloomquist hadn’t previously spoken about. In my story for Car and Driver, I wrote that he declined to talk about it, but actually, he did—off the record. But now that he’s gone, I figure it’s OK now to include it in this story: Bloomquist said that with his mind suitably open, he saw extraterrestrials and ghosts that would visit him in jail at night. That’s the tape I wish I could find, with Bloomquist tentatively, seriously talking about the supernatural. But it’s in a box somewhere, apparently unlabeled…

On a 2023 podcast hosted by Dale Earnhardt, Jr., which has been viewed 254,000 times, an arcane Bloomquist did not hold back with the alien stories, mentioning that he had once seen, on his rural property, a spacecraft filling up with water from the lake next to Bloomquist’s house. “Just something for everybody out there: When the time comes, don’t get on the cigar-shaped ship, get on the saucers. A little friendly advice,” Bloomquist told Earnhardt, his face reasonably straight.

He said that his awakening had come when he was 33, which would have been a year before I first spoke to him. Eventually, Bloomquist went public with his stories, losing some fans who wrote him off as a likely drug-addled, long-haired, tie-dyed kook.

But his fan base continued to flourish, many fascinated by his abstract, so-different persona, not to mention his skill on the racetrack. In the late 1990s, dirt late model promoters like Earl Baltes at Eldora Speedway began offering what was called in the sport “big money” races, which paid $30,000 or more, at least six times what had become normal for a typical race.

Often held on weeknights so drivers could still compete in weekend points races at their home track, the show-up-and-win format was tailor-made for Bloomquist. Between 1994 and 2018, he won at least 42 “big money” races, some paying $100,000, for a total pre-tax take-home of $2,252,000. Visitors to his shop in Mooresburg, population about 1000, marveled at the trophies lining the walls, along with those big “pay to the order of” cardboard checks they give winners to hold up for the cameras. There was also a little glass-fronted refrigerator that held energy drinks and Crown Royal.

Bloomquist changed his car number from 18 to zero, with a yin-yang symbol inside the 0 on one side of his car, a skull and crossbones inside the other one. His merchandise trailer, run by his mother, Georgie, contained moody tee-shirts and hats, many with his “No Weak Links” motto, or “Black Sunshine.” It was savvy marketing when seemingly every other driver was selling shirts with a huge neon car on the back and sponsors on the front for the same $28.

It was estimated that Bloomquist’s merchandise sales at least doubled any other driver’s, then and now. After races, he’d sign autographs and talk to fans until there was no one left waiting. There are still seven pages of Official Merchandise listed on ScottBloomquist.com, much of it scheduled for release this week—mostly the hats and tee shirts that recall Bloomquist in the past tense, such as the “Forever Legend” cap ($38). Halfway through page two you reach present-tense merch, and some is a little creepy: There’s the “Speed Shop Barn Decal” ($8), which features the iconic old, barely-standing wooden barn that he flew his airplane into, and a “Legend” decal ($8) which has an all-capital-letters message: “NOT DEAD YET!” Knowing Bloomquist, he’d get a kick out of those two.

He is missed. “Scott Bloomquist was the greatest dirt late model driver in history,” said Dick Berggren, longtime racer, TV motorsports broadcaster, editor of Stock Car Racing magazine, founder of Speedway Illustrated magazine, and founder of the New England Racing Museum in Loudon, New Hampshire. But Bloomquist wasn’t just a driver. “The innovations he came up with in his cars, everybody tried to steal them, but by the time they stole them, Bloomer would have thought up something else. He had an incredible career, and it’s tragic that the sport has lost him.”

“Bloomer” was, incidentally, Bloomquist’s universal nickname. Even at 60, he was rosy-cheeked, with still-too-long hair and steely eyes that could look right through you. “Bloomer” fit. He could strike a pose like a professional model.

Reid Millard, the man chosen by Bloomquist’s mother to announce her son’s death to the world, met Bloomquist 20 years ago. Millard is a Jefferson City, Missouri entrepreneur, with a chain of funeral homes in Central Missouri, plus Moberly Motorsports Park, a dirt race track. “I’m a businessman who races for fun, and Scott was a businessman who races for a living,” Millard said. They talked frequently, with Millard helping Bloomquist with business matters, and Bloomquist schooling Millard with his dirt late-model racing.

“Scott was really complex, compared to most people. Conversations with him would get pretty deep, like you’d start with the geometry of cars, then move to his religion—he had his own take on that—I mean, he was a complicated guy. Very intellectual. Built his own cars, and marched to his own drum, all the way through life.”

You’d think a driver with Bloomquist’s talent might be able to move up to, say, NASCAR, and Bloomquist made a stab at it, running one of Kyle Busch’s Toyotas in the NASCAR Craftsman truck race that current Eldora owner Tony Stewart brought to his track in 2013. Bloomquist finished 25th. He got too innovative with the front suspension, taking a gamble that didn’t pay off. He raced in three ARCA events in 1991, with an average start of 16th, and an average finish of 30th. Bloomer was a dirt-track driver, and he knew it.

Bloomquist was often viewed as a bad boy, along with dirt-track open-wheel drivers like Kenny Weld and Weld’s longtime rival, Jan Opperman. He followed roughly in their shaggy path, which had been struck in the 1970s by Opperman, whose career was effectively ended by a crash in 1976. “I had been into the hippie scene when it was a fad to have long hair and a pocketful of dope,” Opperman once said in a published interview. “I did a lot of mind-expanding drugs and was into Eastern religions, the whole trip, all the time trying to get into something heavier.”

That wasn’t Bloomer, who just wanted to race, and fish, and when he lived in California, surf with his girlfriend and cruise in his 1957 Chevrolet with the 406 nitrous-spiked V-8. Bloomquist’s father, Ron, was a professional pilot, still nationally known for the World War I-era planes he builds and restores. At 18, Scott left California and moved to the Tennessee farm with his parents after getting a taste of racing, and winning, on the West Coast.

Planes were Bloomquist’s other love. He soloed at age 16, having been taught to fly by his dad. Bloomquist attended flight school, but never finished, and consequently had no pilot’s license. His plane was a 1938 Piper Cub, painted the iconic Lockhaven Yellow—named for Piper’s home was in Lockhaven, Pennsylvania. The tail number was N21821, but that’s really not important since the Cub hadn’t been registered since 2006.

Hawkins County Airport was close to the Bloomquist compound, but the family was all but unknown to Mark Finley, a former crop duster who is now the airport’s operator. “Ron used to come in with some 55-gallon drums and buy some 100 octane low-lead fuel,” Finely recalled, “but I can’t say I ever saw Scott fly into here. I never met the man.” Bloomquist would fly his Cub from the family airstrip, usually, he said, to scout fish in the nearby Cherokee Reservoir.

But one morning last month, according to reports, he was flying the Cub erratically before the plane appeared to line up with the runway, but veered left into the old wooden barn on the property. There was a fire in the cockpit, unusual for a Cub crash, but there were rumors that there was a container of gasoline inside the plane with Bloomquist. The plane hit the closed doors dead-center and then burst into flames. The Cub’s wings didn’t burn—they just sort of collapsed onto the ground.

According to the Hawkins County Rescue Squad: “On August 16, 2024, at approximately 7:47 a.m., the HCRS along with other local, state, and federal agencies were dispatched to the 200 block of Brooks Road in Mooresburg, Tennessee for a report of an airplane crash. HCRS responded immediately to the scene. First responders from Lakeview Volunteer Fire Department confirmed there to be an airplane crash involving a barn that was on fire. HCRS Members successfully extricated the solo deceased occupant from the airplane for transport to an area forensic center.”

Bloomquist leaves his parents, a sister, and his only child, Ariel, an 18-year-old college freshman. Ariel matured Bloomer. “I think with Ariel coming along it calmed him down a lot,” Millard said. “He was a great father—he’d go to her ball games, spending plenty of daddy/daughter time together. She’d spend time at his shop. She was by his side a lot.” Hopefully, Ariel was comforted by a big memorial gathering at Eldora, and another at Bloomquist’s home track, Volunteer Speedway in nearby Bull’s Gap, Tennessee, last Thursday.

The National Transportation Safety Board flew into Mark Finley’s airport the morning after the crash, and by nighttime, they were gone. It was apparently considered a simple case. The report is still being written—“In work” is the NTSB’s term for it—with no indication when it will be published. It could take months.

Frankly, it’s generally accepted in the dirt late model community that it wasn’t an accident. The docile 40-horsepower Cub—that’s the engine the 1938 model came with—is considered one of the easiest, safest airplanes to fly ever built, and Bloomquist had years of experience in it.

If it was suicide, “I don’t want to say it’s a rock star way to go out, but it’s on brand. Only Bloomer would do it that way, and I say that just as an observation. He did it his way,” said Todd Clem, former racer and current co-owner of Ocala Speedway, the oldest continuously-operating track in Florida. Clem, perhaps better known as radio host Bubba the Love Sponge, knew Bloomer, who raced at Clem’s track. “Anybody would have been there for him had they known that he was at such a low point,” Clem said.

“Bloomer was polarizing but so beloved. It’s sad that no matter how bad it was for him, there’s not anybody in the racing community that wouldn’t drop what they were doing and drive to Tennessee to help the guy. He’s a superstar, and no matter what was swirling around him, good or bad, from Tony Stewart to Kyle Larson, he could have turned to anybody for help.”

Indeed, four days after Bloomquist died, NASCAR Cup driver Tyler Reddick dedicated his win at Michigan International Speedway to Bloomer, who mentored Reddick early on when he was competing on dirt tracks. “I can’t help but stand here in victory lane and think of Scott Bloomquist,” Reddick said. “Huge mentor to me. An incredible role model and legend of dirt racing and motorsports. The last few days have been tough, and this really helps it. So this win should go for him, his family, his friends, and all that meant a lot to him. It’s tough. It’s always tough when someone you care about passes away. My thoughts are with him and his family.”

Bloomquist hadn’t won a notable race since 2020. His website still lists five races on his 2024 schedule, all at his signature track, Eldora Speedway in Ohio. But Bloomquist hadn’t won at Eldora in six years, though every year, he’d say this was his comeback season. At the 2024 Dirt Late Model Dream qualifying race in June, he was running fourth when he was sent hard into the wall after contact with Shannon Babb’s car, then flipping, and landing on its roof. Bloomquist emerged, shaken and skinned up but otherwise uninjured. The car was a write-off.

“I never would have expected that out of Shannon,” Bloomquist said after the crash. “We’ll get through it. We’ll fight again. I promise you. I know I’m not done yet, I know I’m going to win more races here.”

The Dream paid $100,030 to win; even last place got $6000. Bloomquist didn’t qualify. Babb did, but finished last.

How heavily that crash weighed on Bloomquist, and how much he may have needed the money, is unclear. Add to that his very recent divorce from wife Katrina, his diagnosis of prostate cancer, discovered during tests for back surgery; his continuing pain from a life-threatening 2019 motorcycle crash on the streets of Daytona Beach, and you can certainly make a case that Bloomquist had a lot on his plate.

But did he kill himself? “Only one person knows, and he’s gone,” said his friend and undertaker, Reid Millard. “I like to think maybe he was picked up at the last second by his alien friends.”

Scott was a great driver one like we may never see again on dirt.

But Scotty lived like on his terms for better or worse and he often paid a big price for it.

I know he was having money issues and health issues were reported and I feel this has led many to feel he decided to do things again on his terms.

Love him or hate him we will have one less great driver on the track.

Not a very good picture painted of Jan Opperman. If you were going to mention him and his life you should have told of how he came to know Jesus Christ as his Lord and Savior. Jesus changed Jan’s life.

A shame.

I do wish the Cub hadn’t been wrecked.

It survived 86 years only to be (seemingly) intentionally destroyed.

There are a lot of Cubs around, but few of that prewar vintage.

Yes, people are more important than machines, but those of us who care about cars and planes, do feel for them.

An early J-3 is like a Labrador… Faithful and easy to like.

As I said, a real shame all around.

RIP…

Crown Royal? Canadian whiskey, eh?

A definite character in life. Prayers for the family left behind mourning their loss.

Memories live on