Media | Articles

Before the Indy 500, the Cobe Cup Was the Midwest’s Greatest Automotive Spectacle

One-hundred and fifteen years ago, with automotive fever sweeping the country and car manufacturers looking to stand out from the crowd, three Indiana communities were preparing to host the greatest automobile race that the “west” had ever seen.

No, it wasn’t the Indianapolis 500. The first running of the “Greatest Spectacle in Sports” was two years and 135 miles away.

It was 1909, and northwest Indiana was gearing up for its own version of the East Coast’s famed Vanderbilt Cup. Chicago investor, entrepreneur, and auto enthusiast Ira Cobe, president of the Chicago Automobile Club, admired the success of the Vanderbilt road races, which were held annually from 1904 to 1910 on New York’s Long Island. Cobe wanted to bring that excitement to the Windy City, but when it became apparent that Chicago’s heavily traveled railroad lines impeded the design of a safe road course, Cobe looked to neighboring communities for help. Residents of Crown Point, Lowell, and Cedar Lake, located just across the state line in Lake County, Indiana, raised their collective hands.

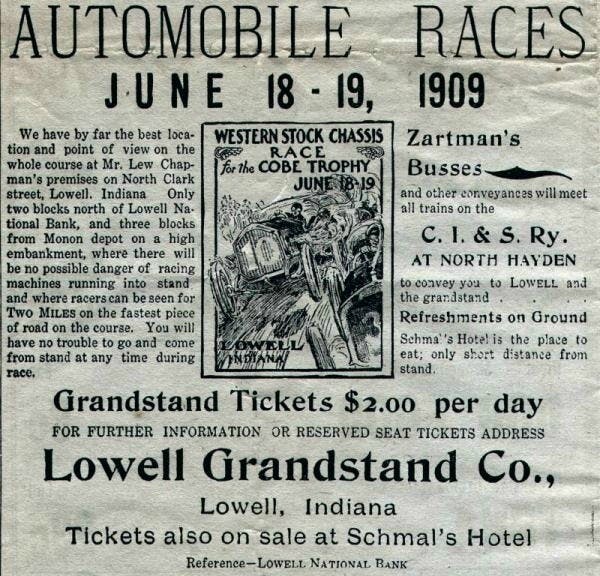

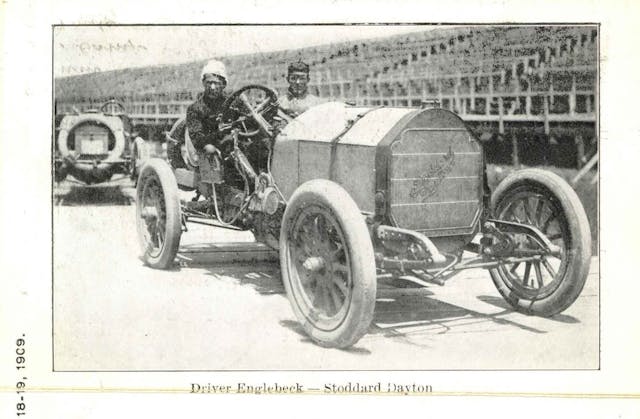

A deal was struck after Cobe promised to make road improvements, and the Cobe Cup was born. Technically called the Western Stock Chassis Races, the weekend event actually consisted of two races: The 232-mile Indiana Trophy, open to automobiles with engine displacements of less than 300 cubic inches, was set for Saturday, June 18, followed by the 396-mile Cobe Cup, open to larger-displacement engines, on Sunday, June 19.

Preparations

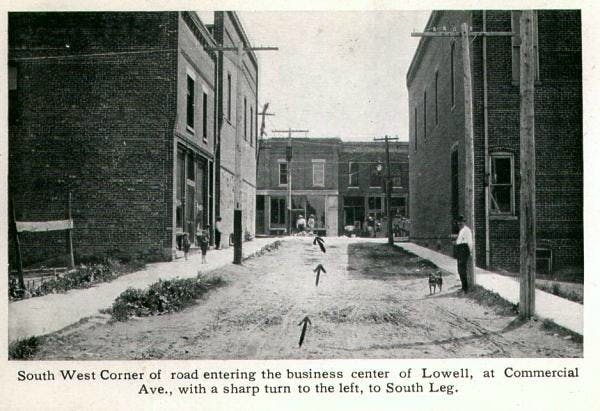

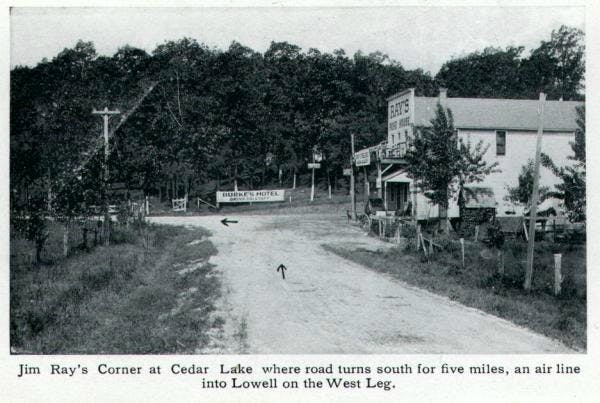

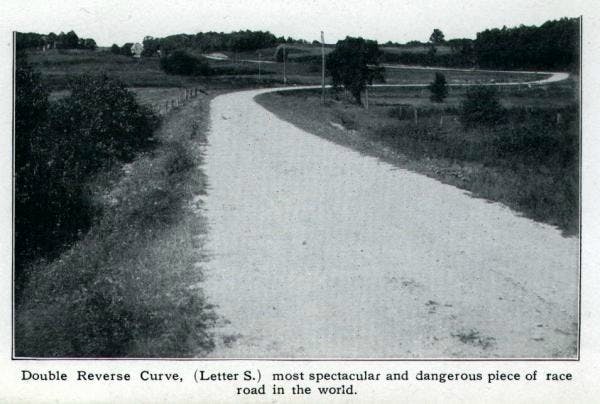

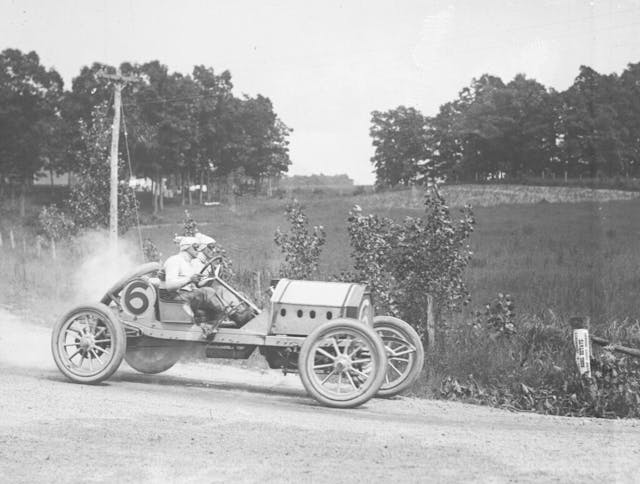

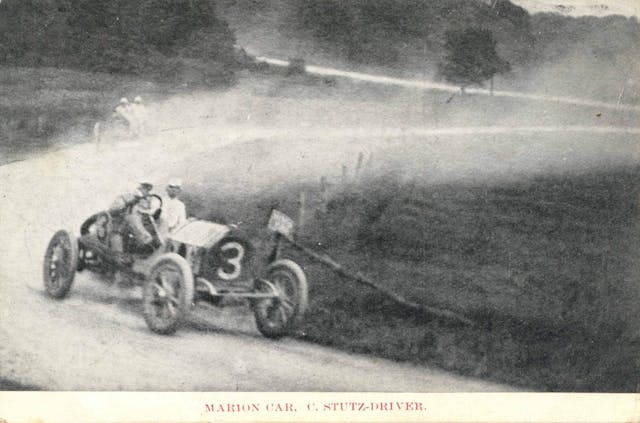

With help from Ira Cobe’s Chicago Automobile Club, a 23.37-mile course was mapped out along Lake County roads and small-town streets. It included an S curve, some hairpin turns, and two long straightaways: a 5.7-mile stretch between Cedar Lake and Lowell, and a 7.1-mile section to the start-finish line near Crown Point. The course was held entirely on unpaved roads, most of which were essentially loose gravel covered in tar. Although the conditions weren’t exactly ideal, they were seemingly perfect for what the Chicago Examiner referred to as “bronzed and brawny men, nerves stretched to the utmost tension, anxiously awaiting the sound of the starter’s pistol, which will send them on their perilous, nerve-racking, and history-making drive.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

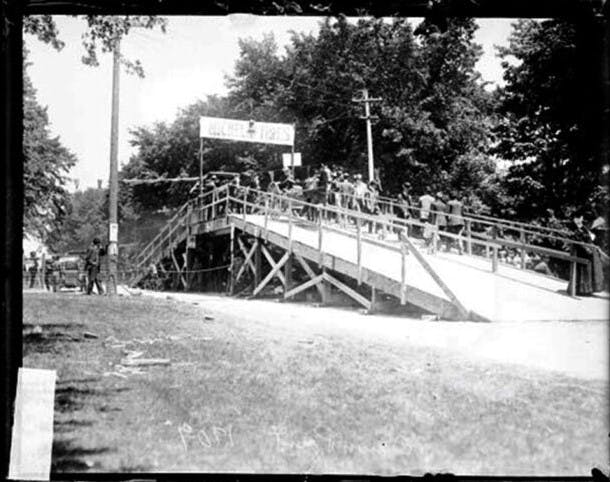

According to longtime Lake County historian Richard Schmal, whose father, Fred, owned a hotel in Crown Point and hosted race fans during the event, two walking bridges were constructed over the raceway, along with an even larger viaduct for horses. “Owing to the immense crowd of people and autos,” a notice in The Lowell Tribune warned, “it will be found necessary to blindfold horses coming in from the country, especially when crossing the viaducts.”

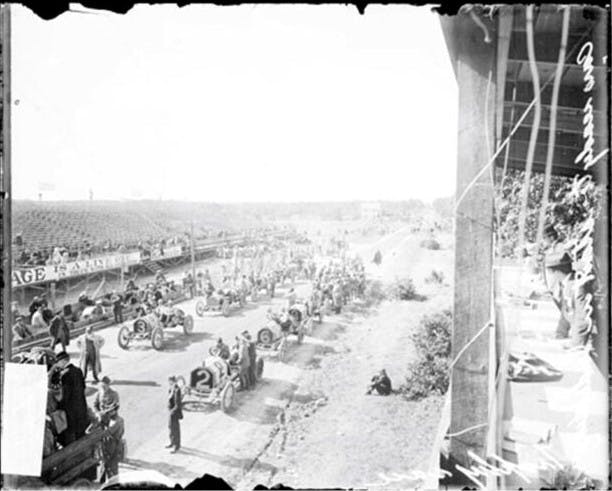

A large grandstand was built near the start-finish line in Crown Point, along with press boxes and a staging/pit area, while two smaller grandstands were constructed in Lowell.

“The (Crown Point) stand was an immense structure in length: 864 feet, in depth: 60 feet, and in height: about 25 feet,” Rev. Timothy Ball wrote in a letter that was later shared in Richard Schmal’s weekly “Pioneer History” column in the Lowell Tribune. “The number of seats: 10,000. Amount of lumber used: 400,000 feet (with) 59 kegs of nails. Contract price for construction: $10,000.”

Advertisements promised patrons that the bleacher seats were “free from the dangerous racing machines … with a two-mile view each way.” Cost of admission was $2, equal to nearly $65 today.

Nine telegraph stations were built to relay standings from one checkpoint to another, and National Guard soldiers were stationed at 40 locations along the route.

With large crowds expected, round-trip train tickets were offered from Chicago, about 50 miles away, aboard the Pennsylvania Railroad. Hotel rooms could be had for $4 a night, and guests could rent chairs to sit on the front porch and watch the races. Farmers offered hitching posts for horse teams, at 35 cents each, and locals looked to make a killing by selling a variety of concessions in and around the grandstands.

“Three hundred men, women, and boys will be ready to pass out 400,000 sandwiches to the automobilists,” The Lake County Times wrote. “There will be no necessity under the present arrangement for anyone leaving his seat in the grandstand during the races, because lunches will be served them at any time.”

The day before the first race, the Times gave a preview of what attendees could expect. “It will be the greatest thing ever seen in the west, and the town and countryside quivers with excitement … You will see a faint tremulous speck in the distance. A red flag flutters in the breeze. You hear the cry ‘car coming,’ and in your veins—as you see the speck get larger and larger, swerving from side to side—the blood burns and the thrill of expectancy grows on you. Nearer and nearer comes the wicked looking machine, half in the air, hurtling, leaping, shaking, containing two weird, goggle-eyed dusty demons strapped in, hanging on for dear life. It hurricanes along in a cloud of dust, spitting like musketry and bounding toward you. The earth vibrates as the demon car hurls itself on, palpitating, swerving from side to side, growning, rattling, chug-chugging and coughing, and you hold your breath as the cheering from thousands rocks the air.”

Race Day Reality

Surprisingly, as the sun rose on race day and the cars got underway, the grandstands were nearly empty. Perhaps the newspapers, despite playing up the thrill of the action, were to blame, scaring away fans by questioning whether there would be enough food and rooms to accommodate the expected throng. Elmer Ragon, editor of the The Lowell Tribune, certainly thought so, and he lamented that fewer than 50,000 people attended both races.

The Lake County Times, perhaps stretching the truth a bit, reported that the towering Crown Point grandstand “held a single paying customer and a brass band.” Another story claimed, “All the grandstands were crowded—with emptiness.”

Maybe there was a lack of paying customers simply because they realized they could watch the race from other points along the course—for free, and in the shade. Instead of paying $2 to sit in undercovered grandstands and purchase the food and drink on sale, many decided to park, sleep, and picnic along the race course, where trees provided shade and, for some, a better view high in the branches.

Different Story on the Track

Although attendance was a disappointment, the competition in the two races was not. In Saturday’s Indiana Cup, Joe Matson was the last of 19 drivers to launch from the starting line—cars started at one-minute intervals—but when the dust and smoke cleared, his 25.6-horsepower Chalmers-Detroit Bluebird placed first. Matson, who the newspapers referred to as the “Durable Dane,” completed 10 laps in 4 hours, 31 minutes, 21 seconds, an average of 51.5 mph. He also had a top speed of 78 mph. (Earlier in the week, Matson scared the living daylights out of Chicago Examiner reporter Delaney Holden, who occupied the mechanic’s seat during an exhibition run, an experience Holden vowed never to repeat.)

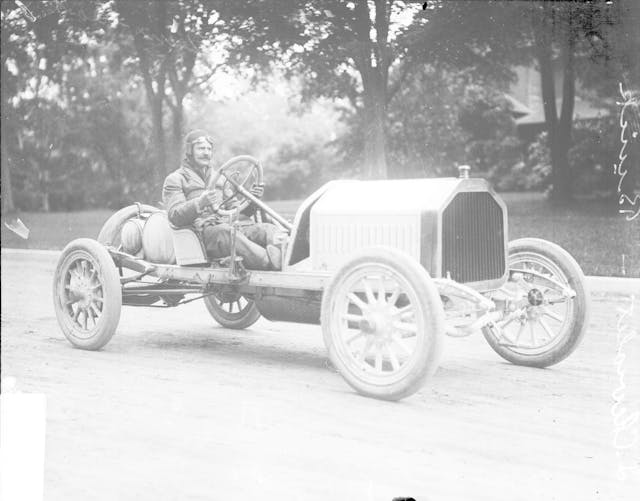

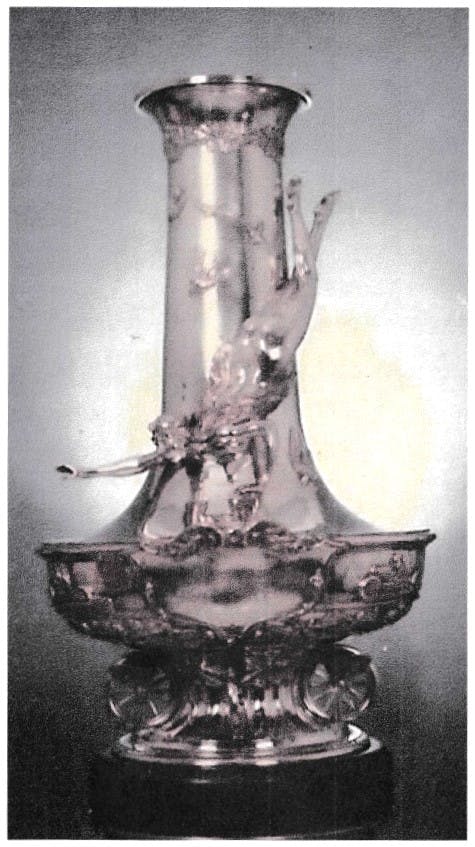

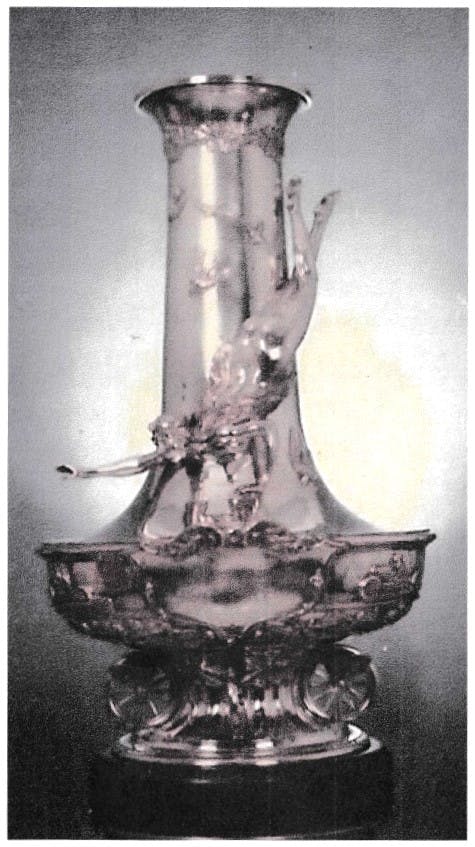

A dozen drivers took part in Sunday’s race for the Cobe Cup Trophy, which included cars built by Buick, Apperson, Fiat, Knox, Locomobile, and Stoddard-Dayton. Again, the final race car off the line also became the champion. Louis Chevrolet, who the press nicknamed the “Demon Frenchman,” drove his Buick to victory, covering nearly 400 miles in 8 hours, 1 minute, 30 seconds. He finished just 1 minute, 5 seconds ahead of Billy Borque’s Knox.

(Two years later, on November 3, 1911, Chevrolet co-founded the Chevrolet Motor Car Company with his brother Arthur Chevrolet, William C. Durant, and investment partners William Little and Dr. Edwin R. Campbell.)

The Cobe Cup course was in such rough shape during the second race that every one of the larger cars averaged less than 50 mph. Chevrolet managed to push his Buick over 80 mph on one stretch, but he had to overcome a blown cylinder to hold off Borque, a feat that the Chicago Examiner applauded by declaring that Chevrolet “won the race on his nerve.”

“The race was run over roads that were in terrible condition,” the newspaper reported. “There were patches on the course that were hardly in shape for travel, and yet the dozen daredevil drivers who faced the starter willingly took their lives in their hands and sent their cars tearing around the course at mile-a-minute speed, turning sharp corners and ploughing [sic] up the rough places with never a thought of the danger that was theirs.”

Driver Herbert Lytle, whose Apperson broke a rear spring and completed only 11 of the 17 laps, told the Chicago Daily News: “The course is in awful shape for a short stretch. If I could have saved the machine in any sort of shape I would have kept running on three springs. [One spot on the course is so bad that] all the cars are slowing up as they strike their running gear … Other parts of the course are fine. This bad spot must be built over if the race is to be run again.”

The Lake County Star didn’t mince words about a potential return. A headline on the front page trumpeted: “THE GREAT RACES ARE OVER. The Crowds Have Dispersed. Thank God.”

A Change of Venue

With the lack of paying customers, promoters lost an estimated $25,000–$40,000 (about $780,000–$1,262,000 today). Although Cobe stated publicly that he planned to give the Cobe Cup another go in Lake County—“I believe we can repeat our races next year … We are going ahead with our preparations”—he soon changed his mind. The Indianapolis News reported in October 1909 that the Crown Point grandstand was being torn down. The newspaper added that the new Indianapolis Motor Speedway, which opened in August 1909, was interested in the lumber.

The Chicago Automobile Club later announced that it would move the Cobe Cup to Indy for 1910. Joe Dawson, driving a Marmon, averaged 73.423 mph and won the 200-mile race, which was held on Independence Day.

The following year, the Indianapolis 500 was held for the first time, and the Cobe Cup was no more.

Indiana Remembers

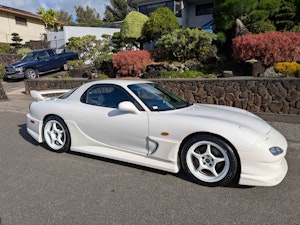

It has been more than a century since Indiana hosted its first major car race, and although the later Indy 500 has received much more fame and adulation, the three Lake County communities have never forgotten the Cobe Cup. In fact, the Regional Streeters Car Club will retrace the original racecourse when it hosts the commemorative Cobe Cup Car Cruise on Saturday, May 25, the day before the 108th running of the Greatest Spectacle in Sports.

“It isn’t exactly the same route,” says first-year Regional Streeters president Bob Schroader, “but it’s close.”

The cruise doubles as a fundraiser for local charities. Beneficiaries have included Shriner’s Children’s Hospital in Chicago, automotive education scholarships, Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis, and Community Health Network’s “Buddy Bags” program, which provides school children take-home meals on weekends.

Last year’s Cobe Cup Cruise included 105 cars, up from 80 the previous year. That’s an encouraging sign for Schroader, who is hoping to add younger members to the club’s membership. While Bob owns a 1947 Ford F1 pickup, and his wife, Susan, the club’s secretary, owns a 1979 Chevrolet El Camino, they say classic car ownership is not a requirement to join the club.

“If you enjoy them and want to be part of it,” Bob says, “we’d love to have you.”

The Schroaders say the annual Cobe Cup Car Cruise requires the cooperation of the Crown Point, Lowell, and Cedar Lake Police Departments, as well as the Lake County Sheriff’s Department and all three communities.

As the 1909 Cobe Cup proved, it takes a village. Or, in this case, three.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Very well written. I’ve participated in the Cobe Cup Cruise over the past number of years and it is a very fun time. Also, a few very rare cars are brought out to do the cruise. It’s a must do for me each year.